We have seen in previous sections that the political developments during the time of the Umayyad Caliphate were profound. The political system in which people were living by the end of the Umayyad Caliphate was in total contrast to the system in which they lived by the end of the Rashidun Caliphate. The changes in the cultural field were even more pronounced. Almost one century of the Umayyad Caliphate’s rule over a vast area of the Middle East transformed the culture of the Middle East forever. Western civilization receded largely. The Iranian civilization contracted in influence. Both gave way to what is called the Islamic Civilization.

Historians politically divided

Historians are divided on political lines about the cultural developments in the Umayyad Caliphate. On one side of the divide are ‘Revisionists’. Their mindset is that everything Muslims believed in and practiced during the era of the Umayyad Caliphate was either present in Pre-Islamic times or it developed only after the death of Prophet Muhammad. On the other side of the divide are the ‘Islamic Apologists’. Their paradigm is that all Islamic beliefs and practices came into existence during the lifetime of Prophet Muhammad and since then they have not changed significantly. 3 Both use the same tactics to prove their point – neglecting available evidence, misrepresenting available evidence, rejecting unfavourable parts of available evidence and banking on favourable but weak evidence. On top of that both are fearful of emerging evidence. We have to be mindful of this divide while studying the cultural changes during the Umayyad Caliphate.

Social changes at a fast pace

Human society has an internal social inertia. It resists social change for a while when the need for change is ripe. It also does not stop changing at a point where the change is enough. Society had largely resisted change during the Rashidun Caliphate. The conquering Arabs jealously guarded their culture and the conquered nations guarded theirs. Now, they started molding.

The pace of social change was extremely fast during the Umayyad Caliphate. It was so fast that a person could easily recognize it during his lifetime. While speaking on one occasion during his journey from Mecca to Kufa, Husayn bin Ali observed, “Indeed the world has changed, and it has changed for the worse.” 4

Even contemporary non-Arabs could recognize changes in Arab society at a fast pace and pondered over its underlying mechanism. The Rashidun Caliphate had appointed Dīnār over Mah Kufa and Mah Basrah to collect kharaj tax. 5 He used to come to Kufa annually to deliver the money by hand. Once he came to Kufa during Mu’awiya bin Abu Sufyan’s time. He addressed to the people there and said, “Inhabitants of Kūfah, from the moment you first came into contact with us, you have behaved irreproachably and you have stayed the same throughout the reigns of ‘Umar and ‘Uthmān. But thereafter you changed and four qualities have gained the upper hand among you: niggardliness, deceit, perfidy and narrow-mindedness, although not one of these marked you in the past. I have been watching you and I have found these characteristics in your Mawla generation (fi muwalladīkum). I also know where you got them. Deceit you derived from the Nabateans, niggardliness from the Persians, Perfidy you copied from the Khurāsānians, and narrow-mindedness from al-Ahwāz.” 6

Islamization of society

The Islamization of society was in its rudimentary phase by the end of the Rashidun Caliphate. The Umayyad Caliphate took it to new heights. Actually, the Islamization of society was the most significant single cultural change in the Middle East during the time of the Umayyad Caliphate.

The Islamization and Arabization of society went hand in hand, yet they were separate from each other. Becker was the first scholar to distinguish between Islamization and Arabization, and he stressed the crucial importance of the interaction of Muslim Arabs with conquered non-Arab populations outside Arabia after Futuhul Buldan in furthering development of both processes.7

The Islamization of society took place in phases. The phases can be best studied in the Iraq province of the Umayyad Caliphate. We hardly hear from the historic sources of any new converts from the start of the First Arab Civil War to the end of the Second Arab Civil War. It appears that the non-Muslims living in the Islamic state were in the pre-contemplation stage. They were not sure of the permanency of the Arab Muslim rule. The eagerness to convert to Islam, which had emerged in the wake of Futuhul Buldan, remained dormant. As Caliph Abdul Malik bin Marwan became all in all at the end of the Second Arab Civil War and as he made Islam state religion, eagerness to convert to Islam surged again. It is evident from the fact that the government started feeling economic pinch of decline in revenues. According to a tradition recorded by Tabari just before the Rebellion of the Discontent in 699 CE, Hajjaj’s officers (‘Ummāl) wrote to Hajjaj, “The land tax has become depleted. The ahl al-dhimmah have become Muslims and have gone off to the garrison cities.” Hajjaj wrote to Basrah and elsewhere, “Whoever originates from a village must go out [and return] to it.” The people who had flocked into garrison towns from the villages after converting to Islam had to leave the towns. They had no idea where to go. They camped outside the towns and began to weep and call out, “O Muḥammad! O Muḥammad!”8 The governmental policies did not hinder conversions. People continued to convert to Islam. The revenues continued to drop. They were at quite a low level during Walid bin Abdul Malik’s government. 9 The situation of the revenues of Iraq did not improve during Sulayman bin Abdul Malik’s tenure. When Hajjaj had died and Yazid bin Muhallab had taken over the office of the governor of Iraq, he still faced the same dilemma – how to raise the revenue of Iraq? 10 Ultimately, the Umar bin Abdul Aziz government had to accept the reality. By that time, one can assume Mawlas were more in number in Iraq than the Arab Muslims.

The Islamization did not take place at an equal pace in all parts of the country.11 Historical sources mention the conversion to Islam was more prominent in certain geographical areas. Iraq was one such area. Others included Khorasan and Ifriqiya. Umar bin Abdul Aziz had to order his officials in Iraq, Khorasan and Ifriqiya to give financial relief and cultural equality to the new converts. 12 Certain population groups had special affinity towards Islam. Almost all new converts in Iraq were Farsi speaking ethnic Persians. 13 The converts in Khorasan and Ifriqiya were Turks and Berbers respectively.14 Islam, generally, did not appeal to the Christian and Jew population of the country.

Instruments of Islamization

The basic classification of the population during the Rashidun Caliphate was that of Muslims and non-Muslims. The department of taxation and the department of justice viewed people in this context. 15 The Umayyad Caliphate inherited this classification. The conversion to Islam was not a private matter, whereby a person could proclaim shahadah and start attending mosque. Conversion had to be registered with the departments of taxation and justice. A Muslim man had to be documented as instrumental and a catalyst of conversion. The question is who converted non-Muslims to Islam? Was it the Caliph and his government or the common people?

We have some telltale stories. When Mus’ab bin Zubayr massacred the Mawlas in Kufa, Abdullah bin Umar raised his voice against the action. 16 Now, Abdullah bin Umar is known to belong to the genre of people called ‘pious Muslims’, and Mus’ab bin Zubayr belonged to secular class of Muslims. Abdullah bin Umar was a religious scholar, known to be a compiler and transmitter of Hadith. Mus’ab bin Zubayr, on the other hand, was a common follower of Islam like any other Muslim. Mus’ab and his companions perceived the Mawlas as opponents who wished to acquire a social status equal to the Arab Muslims. Abdullah bin Umar perceived them as partners and equals. Actually, the massacre of the Mawlas at the hands of Mus’ab bin Zubayr received a loud uproar from the pious Muslims. See a piece of ode composed to denounce the action of Mus’ab:

You killed the six thousand in cold blood

Their hands tied behind them, in spite of a firm pledge. 17

Let us go to another anecdote. When Hajjaj bin Yousuf expelled the Mawlas out of Basrah and ordered them to return to their lands for tilling, it was the Qurra’ who rushed to sympathize with the Mawlas. 18 Again, Hajjaj was a government official whose aim was to collect taxes and to keep the countryside productive. The Qurra’ were a pious element of the society who considered the economic and administrative issues secondary to religious duties.

Here is another story. When Ashras bin Abdullah made a certificate of circumcision or a demonstrated capability to read a portion of the Qur’an a pre-requisite to register a person as convert to Islam, they were the pious members of society who opposed the regulation. They were the one who joined the new converts in their sit in at Samarkand.19 Once again, Ashras was merely a Muslim with main objective to manage the district. The pious members of society did not bother about management. They attached primary importance to conversion.

The caliph, his government and his agents were not instrumental in converting people to Islam. It was the pious element of the society that devoted their lives towards converting non-Muslims to Islam. They were those who did not hesitate in accepting the Mawlas at a position of authority provided the Mawla had a reputation to be a pious person. 20

No surprise, we rarely find a Mawla as the sitting caliph, while we find numberless Mawlas to common people.

Look at the efforts of a common soldier to convert his concubine to Islam. She was a Caucasian Byzantine Roman prisoner of war. Yazid bin Nu’aym bought her and took her to his home in Kufa. There he asked her to convert to Islam, but she refused. When he beat her to comply, she only became stubborner. Seeing this, he ordered her to be ready, and then called for her. She conceived as a result of this intercourse and bore a child by the name of Shabib September 27, 646 CE. As the time passed, she liked her master. During her labour she offered, “If you wish, I will convert to Islam as you asked me to,” He said, “If you wish”. She then converted and was a Muslim when she bore Shabib. 21, 22

Factors of Islamization

Tabari asserts that Umar bin Abdul Aziz wrote to his lieutenant governor Jarrah in Khorasan, “Whoever prays with you in the direction of the qiblah is to be relieved of the poll tax.” As a result of the letter, many people hastened to accept Islam. 23 Islamic sources of history give an impression that the only reason behind conversion to Islam was monetary benefits.

It could be a half-truth. Monetary benefit cannot be the sole factor. Why only Turks, Berbers and Persians took advantage of monetary benefits? Why the Christian majority of Egypt, Syria, or Jazira remained unaffected by Islam? There must be other factors at work.

Hoyland points out mingling of Muslims and non-Muslims as a leading factor of conversion. Again, it could be a half-truth. No doubt, the dwellings of Muslims and non-Muslims were thoroughly segregated during the Rashidun Caliphate. They were not so during the Umayyad Caliphate. More mixing took place in Iraq and Khorasan where a large number of Radif had settled and had took to economic activities other than military service. Still, mingling could have led to conversion in either way. Muslims could have converted to non-Islamic religions in hoards. Why did non-Muslims convert to Islam as a result of mingling?

Did the state not play a role? We know apostatizing from Islam was punishable by death. The state policy might have given a direction to conversion – from other religions to Islam and not vice versa. The state, however, only prevented apostasy from Islam. It did not encourage the conversion to Islam. The stated policy of the Umayyad Caliphate was religious tolerance whereby each religious group was free to practice its beliefs.

The most important factor, often neglected by analysts, was the ‘power of example.’ Muslims were successful members of society. They were comparatively rich, had numerous wives and concubines, could afford large number of children, and dwelled in luxury houses where slaves were ready to act on mere one gesture of eyebrow. Muslims were not only successful in economic terms but also in political terms. They could inflict a number of defeats on non-Muslim powers during Futuhul Buldan and later, could establish a strong state despite multiple infightings, and could make Islam the state religion despite being a minority in the country. Not a single Muslim ever claimed that they achieved all this due to any smartness or bravery. They maintained that they achieved all this due to blessing of Prophet Muhammad, because Allah was on their side, and because they practiced the true religion (Dīn ul ḥaq).

Non-Muslims had all temptations to adopt the ways and the religion of this politically and economically successful group. It particularly applied to those non-Muslims who had the chance to mingle with Muslims, especially when they saw the immediate economic benefit of the tax relief. The ‘power of example’ impressed more on the citizens of ex-Sasanian Iran who had lost their mother state and had nowhere to look for political support. The ‘power of example’ did not work so well on the Christians of the western parts of the country who could look towards Byzantine Rome for political support. The ‘power of example’ impressed those non-Muslims more whose religious beliefs allowed polygamy, like Zoroastrians and Buddhists. Non-Muslims who considered polygamy a sin, like Christians, were less impressed.

Did Umayyads prevent Islamization?

The blunt answer is ‘nope’. A precedent for the ban on religious conversion was present in the Middle East. There was a blanket ban on any kind of religious conversion in Sasanian Iran just before its disintegration at the hands of Futuhul Buldan. 24 The Umayyads could have tried to ban conversions if they really wished to prevent Islamization. They rather maintained the death penalty for apostasy from Islam.

The taxation law of the country prescribed different tax rates for Muslims and non-Muslims. Actually, the names of taxes were different for the two groups. It meant the rationale of taxing was different for different groups. The Umayyads prevented the newly converts from paying tax at Muslim’s rate. Historical sources preserve the argument of Mawlas that they deserved equal rights to their Arab counterparts but they do not mention government’s argument in this regard. Worth noting is that the sulh agreements of most of the communities did not stipulate in black and white that they would be granted same rights and responsibilities which other Muslims enjoy, if they convert to Islam. 25 Such clauses were included only in those agreements which took place in the middle phase of Futuhul Buldan. They were absent from the earliest or the last contracts.

Islamization independent of state influence

The map of Islamized areas by the end of the Umayyad Caliphate does not exactly coincide with the geographic boundaries of the country. Two districts of the Umayyad Caliphate, Armenia and Spain remained rather hostile to Islam. Some areas outside the Umayyad Caliphate, for example Kerala in India, Aceh in Indonesia and Northwest China, started embracing Islam. 26 The state did play a role in Islamization but it was not a decisive factor.

Many religions survive side by side

A mosque still stands in the ruins of Shivta in modern day Israel about 50 km south of Beer Sheeva. Shivta was a small agricultural village during Byzantine times. It survived during the period of the Umayyad Caliphate and was abandoned in either eighth or ninth century CE. The astonishing feature of the mosque is that it shares one of its walls with a church.27 The archaeological find sheds light on the fact that Muslim and Christian communities lived side by side in Syrian villages and had ample opportunity to mingle with each other.

Church and mosque; Shavita ruins. Church in the foreground, mosque in the background. 28

Respect to the tenants of Islam was a requirement written in some Sulh agreements. Non-Muslims would not dare disrespect Islamic beliefs. Muslims were ruler of the country, in any case. As Muslims mingled with non-Muslims more and more, situations did arise where Muslims expressed their disdain towards a non-Muslim religion. In such cases non-Muslims expected that a Muslim would show regard to their belief system, but many a times Muslims did not. A community of Buddhists and Zoroastrians got defeated at the hands of the army of the Umayyad Caliphate in Samarkand. The community paid the army of the Umayyad Caliphate in the form of ornaments of fire temples and idols. Qutayba bin Muslim, the commander of the Umayyad Caliphate, piled an enormous edifice and ordered to burn them to get bullion. The non-Arab soldiers of the Umayyad Caliphate warned Qubayba, “Among them are idols the burner of which will be destroyed”. Qutayba announced that he would burn them with his own hands. Ghūrak, a leader of non-Muslims in the army, came forward, knelt before Qutayba, and said, “Devotion to you is a duty incumbent on me. Do not expose yourself to these idols.” Qutayba burned them and got fifty thousand mithqals. 30 In this incident, at least, Muslims did not show respect to the belief system of non-Muslims, though they expected it.

Language

Generally, the language a customer prefers is the language of a market. The seller has to be proficient in that language. The Umayyad Caliphate stretched from the borders of China to those of France and from the borders of Russia to the Horn of the African Continent. It was a big market. It had as many linguistic ethnicities as there are days in a year. All of them were mainly sellers. The only linguistic ethnicity which was a net buyer was Arab. They were rich and patronized all kind of goods and services. Government was the biggest single buyer to the extent that it had oligopsony in the market. It was natural for their language, Arabic, to be the dominant language of the country. 31

Arabic had already become an official language in Egypt during the Rashidun Caliphate. 32 Caliph Abdul Malik bin Marwan made the Arabization of the whole country a flagship of his government. Baladhuri provides details on how he displaced Greek in the western provinces of the country with Arabic. He tells that Greek remained the language of state registers until 700 CE. Abdul Malik took an excuse from an event in which a Greek clerk desiring to write something and finding no ink urinated in the inkstand. In retaliation, Abdul Malik ordered Sulayman bin Sa’d to change the language of registers. He paid Sulayman one year’s tax of the district of Jordan as his fee (Ma’ūnah) for it. When Sulayman prepared a sample of the register in Arabic, Abdul Malik showed it to Sarjūn [Sergius]. He presented to Sarjun the detailed plan of change of language. Sarjun was greatly chagrined and left Abdul Malik’s company in a sorrowful mood. Meeting certain Greek clerks, Sarjun said to them, “Seek your livelihood in any other profession than this, for God has cut it off from you”.33 So there was a resistance from the bureaucracy towards such move because they feared their jobs. Abdul Malik brought the change tactfully posing it as a punishment for the indecent act of one of the clerks.

According to Baladhuri, Pahlavi was language of the register of the kharaj of Sawad and the rest of Iraq until Abdul Malik’s time. Hajjaj bin Yousuf had appointed a certain Ṣalīh bin ‘Abdur Rahmān as his chief secretary. Salih was a son of a slave from Sistan who had attained the status of Mawla after winning freedom at the hands of Tamim after converting to Islam. Salih was well versed in both Arabic and Persian. Hajjaj had dismissed his long-standing chief secretary, Zādān Farrūkh bin Yabra, to appoint Salih. Salih had previously served as an assistant secretery under Zadan. Reportedly, Salih and Zadan had an enmity when both were in office. Probably the basis of the enmity was a clash between the two on the status of Pahlavi as an official language. As soon as Salih became chief secretary, he proposed to Hajjaj to dump Pahlavi for Arabic as the official language. Hajjaj promptly accepted the proposal. Zadan was murdered soon after but his son Mardānshāh campaigned against the launch of Arabic. The Pahlavi-speaking clerks offered Salih a bribe of hundred thousand dirhams to convince Hajjaj that replacing Pahlavi with Arabic was an impractical wish. Salih refused the offer. He worked hard in that direction. He compiled a small Pahlavi Arabic dictionary to facilitate the task. He translated Pahlavi dahwiyah and shashwiyah to Arabic ushr (tenth) and nuṣf ushr (half-tenth). He also changed wīd (access) to aiḍan. 34 So, again, we see that the exixting bureaucracy was against such move because it threatened their jobs. Hajjaj had to use tactics to introduce Arabic.

The reason for the change in the official language could be inability of the caliph and the governor to understand non-Arabic languages. Giving a hint, Baladhuri reports that Hajjaj had to depend solely on Pahlavi speaking officers to deal with the register when the language of the register was Pahlavi. 35 Pahlvi did not disappear from face of Iran quickly. Its last known text is available from 1323 CE.36

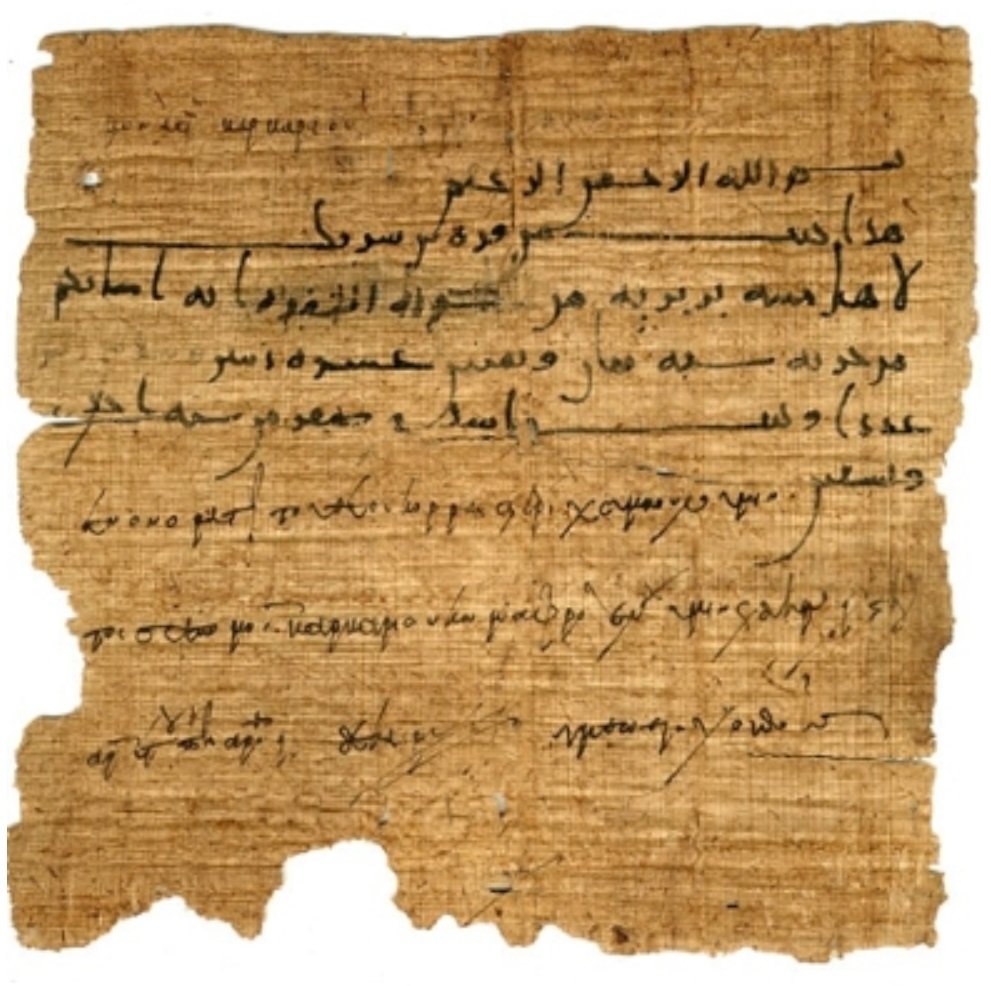

Administrative papyri, which have survived from Egypt, provide more concrete evidence of replacement of Greek by Arabic. They enable us to see a gradual change from Greek to Arabic in the language of administration. They further elaborate that the change in official language was not that dramatic as Baladhuri suggests. It was gradual. 37.

Bilingual tax invoice from Egypt. 38

The Arabization of society was broader than the mere change of the official language of the country. It was the spread of the Arabic tongue as a language of daily use. According to Hawting ‘Arabization’ was distinct from Islamization. The communities of Jews and Christians survived in the Islamic Middle East up to modern times. These communities maintained their religious traditions in spite of the fact that they had renounced the everyday languages which they had used before the Arab conquest and had adopted Arabic. Conversely, Iran largely accepted Islam as its religion but maintained its pre-Islamic language at first in everyday and later in literary use, although, of course, the language underwent significant changes in the early Islamic period. 40, 41 The changed version of Pahlavi was Farsi.

Any attempt to chart the progress of the Arabization in the Umayyad Caliphate faces difficulties. They arise from the lack of explicit information on the topic in literary sources and from the paucity of written material surviving from the Umayyad Caliphate. For instance, although it has been suggested that Jews of all sorts began to speak Arabic as early as the seventh century, the earliest texts written in Judaeo-Arabic (that is, the form of Middle Arabic used by Jews and written in Hebrew rather than Arabic script) come from the ninth century. The earliest Christian Arabic texts (Arabic written in the Greek script) have been dated to the eighth century. 42

Eventually, we know, the adoption of Arabic for most purposes became general in Syria, Iraq and Egypt while the Berbers and Persians, in spite of acceptance of Islam and therefore of Arabic as their sacred language, continued to use their own languages for everyday purposes. We can assume that Arabization, like Islamization, progressed a long way under the Umayyad Caliphate, but precise evidence is hard to come by. 43

What led to the adoption and rejection of Arabic by non-Arabic speakers is obviously a very complex question involving the consideration of political and social relationships as well as more purely linguistic ones. 44

Here one has to take into account that Arabic itself changed as it spread in the process of the interaction between Arabs and non-Arabs. As the non-Arab people adopted Arabic, so their own linguistic habits and backgrounds affected the Arabic language, leading to significant changes and to the formation of different dialects. The result of this evolution was Middle Arabic as opposed to Classical Arabic, which is identified with the language of the Qur’an and of the pre-Islamic poetry.45 The change in Arabic dialect from that of classic Arabic to Middle Arabic in Kufa was apparent to its Arab people. 46 Some Arab residents of non-Arab areas jealously guarded their language against foreign influence and transmitted it to their next generation in pure form. Hajjaj came across an Arab who was born and raised in Khuzestan and was a clerk in Khorasan. He corrected Hajjaj’s grammatical mistakes, though Hajjaj had the opportunity to live in Hejaz for many years. Hajjaj was so impressed by his aloquence that he could not resist asking how he learnt the language. He said he learned it from his father’s tongue. 47

Arabs also continued to learn new languages as they progressed further away from the Arabian Peninsula and came into contact with peoples further apart. Tabari introduces an Arab to us who could speak better Turkish with the Turks in Khorasan than a Mawla born and raised in Darqīn. 48 Lastly, as Pahlavi speaking ethnicities resisted Arabization successfully, Arabs did not have any problem in adopting their language to communicate with them. 49

Tribe

Social changes in human society are reactive rather than proactive. As a reaction to the ground realities of the Umayyad Caliphate, specifically a strong state and wider distribution of Arab people, the tribe underwent such a change that it became entirely different in character from the pre-Islamic Arab tribe.

The tribe’s role of protecting lives of its members by demanding blood money or vengeance was a thing of the distant past. An ode composed by Ka’b al Ashqari of Azd tribe, a soldier of Muhallab’s army fighting in Kerman against the Kharijies in 696 CE elaborates it:

The dead there had no blood price and no vengeance;

Our blood and theirs flowed unrequited. 50

By the time of the Umayyad Caliphate, the state had established an unchallenged monopoly over violence. It was solely responsible for protecting the life of its citizens and carrying out the death penalty if the need arose. The tribal culture and attitudes, however, persisted throughout the Umayyad Caliphate. Anecdotes of vengeance for murder from certain individuals can be picked easily. 51

The members of a tribe, when confronted with danger, expected that their tribesmen would come to their rescue, just like pre-Islam. The tribesmen, however, did come to the rescue only if such action did not involve serious risks. In case of excessive risk, they abandoned their fellow tribesman to his own. 52

Not only the tribe’s role, its structure changed tremendously. Ancient Arab tradition of senior most member of a tribe-attaining role of Shaykh after death of a leader disappeared permanently. Now all positions of a tribal leader were filled by government appointees.53

A tribe no longer remained a group of people who claimed to be descendants of a common reputed ancestor. It became a government generated military unit, purely of administrative nature. Ziyad bin Abihi/Abu Sufyan organized military in cantonments of Iraq into new kind of divisions. He amalgamated many different tribes into four divisions in Kufa and five divisions in Basra. 54 The commander of each division was not necessarily a member of any of the tribes included in that particular division. 55

Due to the changes in the role and structure of tribe, many lost incentive to remain stuck to their original tribe. What is the advantage of being a member of a tribe if one has to rely on his own sources in case of threat to his life from any quarter, including state? In addition, what is the advantage of sticking to the original tribe when the government can group that tribe with any other tribe just for administration, without taking into account pre-Islamic affiliations or hostilities? For the first time in the history of Arabs, we see abrupt change in a reputed ancestor if need arises. It was mainly for political gains. 56 Once Bajilah tribe changed its reputed ancestor. An ode of Thābit Quṭnah composed in 727 CE taunts them:

I see every people know their father;

While the father of Bajīlah wavers between them. 57

The use of their tribe as identity card lost its steam. Arabs had scattered far and wide. No one knew anybody else personally. It was as easy for an individual to change his tribal identity as winking.58

As a result of new developments tribal identity no longer remained the only identity card of an individual. Arabs still attached significance to tribal identity, but it became unreliable.

It does not mean tribal identity disappeared altogether. It persisted. 59 It was adhered to more by those who saw social or political advantage in it. No surprise, those involved in tribal chauvinism expressed their tribal identities more than others did. A dated inscription of 100 AH mentions the hajj of the tribe Azd and askes for paradise for all of them. It is found in Abū Ṭāqah on the hajj route in Saudi Arabia. 60 Similarly, a coin of 691 CE, issued by Maqātil bin Misma mentions Bakr bin Wa’il. 61

Coin mentioning Bakr bin Wa’il.62

On the other hand, there was a big group among Arabs who considered their tribal identity contrary to the spirit of Islam. They shunned from producing their gaeneology, even at a time of dire need. 65

Finally, though hierarchies based on money, vocation, ethnicity or religion had appeared in Arab society, tribal based hierarchy maintained some value. Soldiers preferred to fight against a man of equal tribal status in a duel. 66 Known tribal lineage and reputed piety were the only two criteria on which the reliability of a witness was judged. 67 When someone had to praise a person, he had to mention the nobility of his ancestors and not his wealth. Nasr bin Sayyar, the deputy governor of Khorasan in July of 738 CE said about Hisham bin Abdul Malik: Abū al ‘Āṣ is his ancestor, and ‘Abd Shams; Ḥarb and the generous, noble lords; And Marwān is exalted, the father of the Caliphs, upon whom; Praise is exalted, he being a standard for them.68 Ubaydullah bin Abu Bakrah had become a rich man. Abu Bakrah was a son of Sumayyah, the half-brother of Ziyad bin Abihi/Abu Sufyan. Once a common soldier under his command taunted him that his only nobility was his orchard and his bath, meaning he could not produce any noble name in his ancestors. 69, 70

As the significance of the tribe started to reduce to the level of a mere surname, people found it easy to pick any political side they liked. The tribe, or even the clan, was no longer a political sovereign. By the end of the Umayyad Caliphate, each individual was free to make his own political decisions. Such attitude was present during the Prophetic times and later during the Rashidun Caliphate to a certain degree. Now it became the norm. A man of Abdul Qays by the name of Yazīd bin Nubayṭ joined Husayn bin Ali to fight on his side along with his two sons. This Yazid had ten sons. He persuaded others to join Husayn but they flatly refused. Rather they warned Yazid of the rage of Ibn Ziyad and his companions. 71 During the same fight, we find a man of Ansar fighting on the side of Husayn while his real brother fighting on the side of Umar bin Sa’d. 72 The one who came to fight against Abdullah bin Zubayr was his own brother ‘Amr bin Zubayr.73 Such behavior was not limited to individuals for the sake of political benefits. Even clans and tribes had the same attitude. At the time of the murder of Walid II, the people of banu ‘Āmir of Kalb were with both sides.74

Since tribe survived as a social structure, the government was not aloof to the tribal identity of its citizens. It took into consideration the tribal affiliation of a person before assigning him any task or taking political decisions about him. 75

Geography-based identity

As tribal identity eroded, geography-based identity became more prevalent. Encouraging his Khorasani troops to fight for him, who were from Kufa and Basrah divisions, Qutayba bin Muslim asked them, “for how long will the Syrian army continue to lie in your courtyards and under the roofs of your homes?” 76 This is a typical example of identity based on geography. In the Umayyad Caliphate, we hear about more and more of people whose tribal identity is not known and they are known only by their geographical identity. 77 One can assume that initially tribal identity went hand in hand with geographical identity. Later on, only geographical identity was enough. 78

Mature Arab Nationalism

“Though Arab identity certainly existed before Islam, it was the conquests that entrenched it and spread it and the early Muslim rulers, who commissioned writers and poets to give it substance and shape”, asserts Hoyland. 79

Referring to Arabs in general, rather than Muslims, once Mu’awiya bin Abu Sufyan declared, “By Allah, it is the sovereignty which Allah brought us.”80

During Marwanid times, as opposed to that of Sufyanids, Arab nationalism focused more on Muslim Arabs. After giving a lengthy sermon to his soldiers about the promise of paradise for martyrs and Qur’an’s teachings, Attab bin Warqa, the commander of Kufan forces against Shabib in July 696 CE, gave the stage to sermonizers and those who recited the poetry of ‘Antarah.81 This is a clue that both religious sentiments and Arab nationalism was used to encourage soldiers.

Crossbreed Arabs

Despite the maturation of Arab nationalism and widespread Arabization, Arab nation underwent thorough biological diversification.

Describing the appearance of Abbas bin Walid bin Abdul Malik, Tabari tells us that he had blue eyes and red skin, his mother being a Greek.82 If we believe Tabari, Abbas’s appearance was that of a Caucasian man. He was a blue-eyed blond.

Abdur Rahman bin Muhammad addressed his troops just before the war of Dayar al Jimajim. His aim was to challenge the widespread notion in the Umayyad Caliphate that only a Quraysh was entitled to be a caliph. He said, “The Banu Marwān are reviled on account of [their] blue-eyed mother (al Zarqā’). By Allah they have lineage no better than that.” 83 His point was that the ruling elite had been diluted by interbreeding with non-Arabs to that extent that one could hardly believe in their Arab or Quraysh ancestry, if one takes into account the race of their mothers.

Arabs had a patrilineal lineage. Despite descanting voices, as that of Abdur Rahman bin Muhammad, they continued to call themselves Arabs. Hoyland sums up that Arab was just a title by the end of the Umayyad Caliphate, just like we have a title of ‘American’ these days, which does not represent any race but a nation.

Further, the product of a Muslim Arab man and Muslim Arab woman was rare. Islamization was stalled among the non-Muslim Arabs of Iraq and Syria after initial conversions during the first phase of Futuhul Bludan. 84 The majority of those Muslim Arabs who were a product of both Arab parents were offsprings of Christian women. Governor Khalid bin Abdullah al Qasri, for example, was a son of a Christian woman. 85

Mawla Muslims

As Islamization spread in the country, the number of Mawla Muslims bounced. They increasingly participated in the religious activities of Islam. Jabalah bin Farrūkh was a transmitter of historical traditions about Khorasan. 86 Ḥanbal bin abi Ḥuraydah, marzban of Quhistan, relayed many historical traditions.87

Mawlas were officially a part of the Arab tribal system. 88, 89 Still, they did not forget their roots. Many of them took pride in their non-Arab ancestry. Abdul Malik bin Alqama, for example, was a brave Khariji who killed many soldiers of Wasit even without use of a helmet or breastplate. He was proud to be a descendent of the Kings of Persia. 90

Religeose Arabs loved the Mawlas. 91 Secular Muslim Arabs, on the other hand, harbored grudge against them. 92 The basic reason for the grudge was the increasing assertiveness of the Mawlas to attain an equal status to the Arab Muslims. 93 Actually, almost all Mawlas in the cantonment town of Kufa were Pahlavi speaking.94 As Arabs of the town were mostly descendants of an Arab father and a Persian mother, the Mawlas had started claiming that they were of the same creed as were Arabs. 95

However, the grudge of secular Muslim Arabs against Mawlas was not irreversible. Arabs sometimes, expressed gratitude and love to a Mawla, who had done something good for them. Yazīd bin Siyāh al Uswārī was a Mawla who fought bravely to protect Medina from the invading force of Hubaysh bin Duljah in the battle of Rabadhah. He even managed to kill the commander, Hubaysh. When he returned to Medina, the people of Medina poured so much perfume on him and anointed him that his white clothes turned black. 96

The Mawlas had their own hierarchal varieties. When Muslim bin Dakhwan, who was a Mawla, went in the presence of Marwan bin Muhammad, the governor of Jazira and Armenia in 744 CE, Marwan asked him to introduce himself. Muslim answered that he was Muslim bin Dakhwan, a Mawla of Yazid III. Marwan bin Muhammad then asked if he was a manumitted (‘itāqah) Mawla or a voluntarily commended (tibā’ah) Mawla? Muslim told that he was a manumitted Mawla. Marwan said, “That is better.” Then he said, “There is merit in both kinds.”97

The Umayyad Caliphate used to uproot people and root them in remote areas for political management of the country. The Mawlas had their share. Ziyad bin Abihi/Abu Sufyan sent some of Ḥamrā’ Daylam of Kufa to settle in Syria on the orders of Mu’awiya. They were called al Furs (Persians) in Syria. Ziyad also sent some of Hamra’ Daylam to Basrah, where they combined with the Asawirah (Persian cavalry). 98

Slaves were entirely different social group. Muslims, even Mawlas, did not accept them equal. Many runaway slaves had joined the cadre of the army that Abu Muslim had prepared in Khorasan. Initially Abu Muslim lodged the slaves in the same camp where he had organized lodging of the rest of his army. Later, he was compelled to lodge the slaves in a separate camp. His army, which mainly comprised of Mawlas, probably didn’t like the presence of runaway slaves in the same premises.99

Inter-ethnic relations

The Umayyad Caliphate was home to many different populations, living over such a diverse geographical area, and having very little in common with each other. Dealing with all the cultural changes in all population groups of the country from pre-Islamic times to the end of the Umayyad Caliphate in one continuous narrative is unusable. The historians of Islam focus their attention on changes among Muslims to keep the narrative meaningful. They deal with the cultural changes in other population groups in the context of changes in Muslim society.

All of the population groups of the Umayyad Caliphate underwent significant cultural changes during the century of Arab rule. The stimulus of the change was not Futuhul Buldan, as a result of which Arabs came to power over the whole of Sasanian Iran and half of Byzantine Rome. It was the mingling of the Arab elite with different population groups in their common abodes that brought changes. Arabs remained isolated from other groups for a few decades after Futuhul Buldan. Hawting is convinced that mingling of the Arabs with local populations started after the end of the Second Arab Civil War. It was already in full swing by the time of the Rebellion of the Commons.100 According to Hawting, the “numbers of non-Arabs now began to accept Islam and become mawali while many Arabs ceased to have a primarily military role and turned to occupations like trade. The gradual breakdown of the barriers between the Arabs and the subject peoples which ensued meant that the old system, which depended upon isolation of the conquerors from the conquered peoples, became less feasible.101.

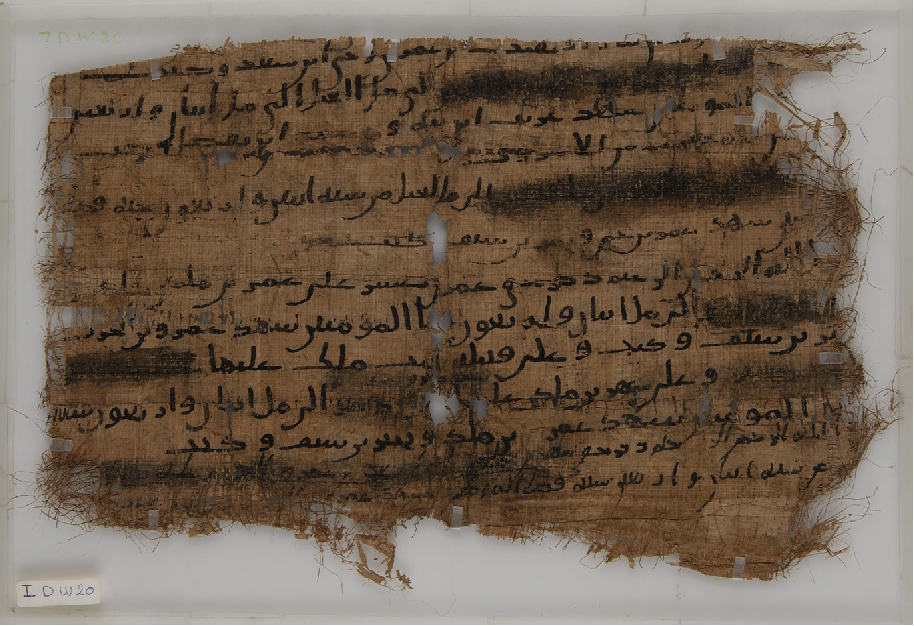

Soviet historians in Central Asia discovered a letter written in Arabic on a parchment in 1934. By using the biodata of the names mentioned in the letter, the manuscript can be dated from January 718 to April 719 CE. The letter was written by a certain Dīwāstī to the lieutenant governor of Khorasan Jarrah bin Abdullah. Diwasti calls himself a servant to the amir Al Jarrah, which gives an impression that Diwasti was a junior government officer. The letter is about a very humble request to al Jarrah for a favour to Diwasti and his son Tarkhun. Though Diwasti is still unidentified character, his name and his son’s name indicate that they might be Turks and still non-Muslims. Yet the letter starts with formula “In the name of Allah, the Compassionate and Merciful”. Then the sender of the letter addresses to Jarrah, ‘Peace be upon you, O amīr and Allah’s mercy” (aslam ‘Alyka, ayyoha al amīr, wa raḥmat Allah). Proceeding further, and before coming to the point, the sender writes, ‘praise be to Allah besides whom there is no god’. (fa innī aḥmad ilayka illalah allazī la ilahah illal huwa). The letter ends with the same greetings, ‘Peace be upon you, O amīr and Allah’s mercy” [aslam ‘Alyka, ayyoha al amīr, wa raḥmat Allah].102 The style of the letter gives an impression that many non-Muslim Turks, especially government servants, had adopted Arabic and Arab/Islamic mannerism, though they had yet not clearly departed from their original culture and religion.

Textual historical sources record a number of instances which point out those non-Muslims of ex Sasanian Iran were well familiar with the Arabs’ culture and psyche. That was the reason a dihqan of Iraq advised governor Khalid bin Abdullah al Qasri that what he had earned and hoarded would be too much in the eyes of Hisham bin Abdul Malik, if he comes to know. 103

The Arabs living in ex-Sasanian Iran had also adopted elements of Iranian culture. Indirect proofs for this hypothesis are abundent. Just look at one name. He was Sirḥān bin Farrukh bin Mujāhid bin Bal’ā’ al ‘Anbari Abu al Faḍl. He was in charge of armed guards in Tus in 743 CE.104 It sounds as if Arabic names of earlier generations changed to Persian ones in later generations.

Moral standards

Pre-Islamic Arab muru’ah not only survived but thrived. It became a cornerstone of Islamic civilization, adopted by many non-Arabs. Advising his sons at his deathbed, Muhallab bin Sufrah tells his sons, “Prefer generosity to miserliness. Love the Arabs and do good [to them]. An Arab is a man to whom you can make [no more than] a promise and he will die in defense of you; how then [do you think] he will behave [if you have done him good] in war?”105

Sticking to high muru’ah was a praiseworthy characteristic of an Arab’s personality. Praising Nasr bin Sayyar, the lieutenant governor of Khorasan in 741 CE, a poet says:

You will win to your side one whose Muru’ah has reached its zenith;

and whose Lord has singled him out for His favour.106

Avoidance of killing the genre

A concept that stemmed from Muru’ah and existed in the society of the Umayyad Caliphate was that destroying the progeny of anyone was immoral. When Ubaydullah bin Ziyad ordered the physical examination of Ali bin Husayn, the report came that he had attained majority. Ibn Ziyad ordered his execution. Zaynab asked, “Will you let any of us survive?”107 The argument was so strong that Ubaydullah had to withdraw his orders.

Justice system

The justice system is the most imperative civic institution of any given society. It affects the lives of common humans more profoundly than the government in the long term. It has the capacity to shape the political, social, and economic culture of a society.

For centuries, humans have pondered over the nature of justice. The first human being to challenge the neutrality of justice was Plato (c. 428 BCE – 348 BCE). The character of Thrasymachus in his famous drama ‘Republic’ argues that justice is the interest of the strong – merely a name for what the powerful or cunning ruler has imposed on the people. 108 This assertion is true to some extent. Common observation is that during eras of absolute monarchs, the sovereign was the most powerful person of the land. He had the sole right to promulgate or modify a law and to design the delivery of justice. Still, an absolute monarch did not actually possess ‘absolute power.’ He could not convert his each and every wish into a law. He had to be mindful of practicality of a law, general economic conditions of the land, and the cultural norms of the people when devising laws. Any law that was not practical, that made economy stagnate or was in direct contradiction with cultural norms would not survive for long, even if it was the deepest wish of the ‘powerful’. That was the reason the absolute monarch never claimed that his person was the source of the law. He always maintained that the Supernatural Being had imparted him the law or had bestowed him with authority to devise law. The Code of Ur-Nammu, that dates from C. 2100 – 2050 BCE and is the first written law ever known to mankind, was claimed to have been imparted by An and Enlil to king Nammu.109 The argument continued. The law of Hammurabi, the first written law known in its totality, was also imparted by Shams to him.110

Allah gave the law of the Umayyad Caliphate through the medium of Prophet Muhammad. When laws are applied in real life, they need explanations, interpretations, and elucidations. In addition, as the society changes, the laws need adaptation. The caliph claimed to be the guardian of Allah’s revelations and His laws.111 The person of the Caliph was the source of the law in the Umayyad Caliphate on the behalf of Allah. The Caliph never claimed that he had direct guidance from Allah. Rather he maintained if he enacted contrary to Allah’s will, Allah would depose him.

The Caliph was the chief justice of the country. All decisions taken by the lower courts of the country presumably had a nod from the Caliph. The move of the political system from inclusivity during the Rashidun Caliphate to autocracy during the Umayyad Caliphate reflects in the the justice system of the country.

Initially, the Mu’awiya bin Abu Sufyan government maintained the separation of governors and judges up to the provincial level. 112 It was not Mu’awiya government’s policy. It was what it had inherited from the Rashidun Caliphate. Gradually the deliverance of justice became a sole prerogative of a governor, as the governor was proxy to the Caliph. 113 The provincial judge became merely another government officer, a sub-ordinate to the governor. 114, 115 The governor routinely presided over court cases. The judge relieved the governor when the governor did not have enough time.116 The governor became the sole authority to hire and fire judges. 117, 118 In this way, the provincial administration lost the oversight of judiciary. This change was a blow to the integrity of the justice system. The governor could easily use his authority as a judge to prosecute his political opponents. 119

Another change was practically annulation of the right to appeal. The Caliph did not bother to review the judgements imparted by the lower courts.120, 121 The only exemption is the brief period of Umar bin Abdul Aziz’s judicial reforms. 122

One of the reasons that Caliph Mu’awiya bin Abu Sufyan had to make judiciary subject to provincial governors could be that the judges no longer remained neutral and nonpartisan during the First Arab Civil War. A typical example comes from the case of judge Surayh bin Harith. Surayh started serving as a judge of Kufa during the caliphate of Umar bin Khattab. He continued to serve under Uthman bin Affan. When Ali got control of Kufa, he dismissed Surayh. The charge was that Surayh had become Shi’a Uthman. 123 Mu’awiya bin Abu Sufyan restored Surayh to his position after assuming power in Kufa. 124 This time the appointment would be purely political in nature. Surayh continued to serve in that position until Mukhtar al Thaqafi became the ruler of the province. 125 Mukhtar was Shi’a Ali. He sent Surayh on sick leave. 126 Mukhtar’s open objection to Surayh was his role in the case of Hujr bin Adi. Mus’ab bin Zubayr, after attaining power in Kufa, converted Surayh’s sick leave into termination. 127 When Abdul Malik became ruler over Kufa he once again restored Surayh. 128 Surayh became the longest serving judge during early Islam. In 698 CE, he took a voluntary retirement. Probably, working under the supervision of Hajjaj was too much for Surayh.129, 130

The four crimes that carried capital punishment during the Rashidun Caliphate continued in their original shape. 131 Killing a person in self-defense did not amount to murder in the legal system of the Umayyad Caliphate. 132 Sometimes an eyewitness of murder killed the assassin on the spot without waiting for court verdict. This kind of cases mostly arose from a situation where the murdered was from higher social status and the killer was of lower social status. 133 The mode of carrying out the death penalty in the murder cases remained the standard procedure of separating head from the body by the single stroke of a sword for the common murderer. 134

A fifth crime was added to the list of crimes that carried capital punishment. That was the death penalty for miscreants (mufsid). The government used it extensively. As the governor was the prosecutor as well as the judge, he could easily label any opposition figure to be a miscreant and kill him. This clause also applied to such criminals as dacoits. We hear of very few death penalties for the other four crimes. The majority of court cases that have reached us were about miscreants. The mode of death under this punishment was at the discretion of the judge/governor. The court strived to inflict as much physical, mental and spiritual torture to kill the condemned as possible. 135, 136

As tribal attitudes persisted, if the family or friends of a slain considered that the government had failed to provide justice, they took the law in their own hand to kill the murderer. In almost all cases, the murderer was a government officer who acted in line of his duty. The family and friends of the slain, on the other hand, did not consider that the officer had acted lawfully. 137

Adultery committed by a married person carried the death sentence by stoning, as was the case during the Rashidun Caliphate. However, we don’t find a single incidence of this punishment being carried out in the Umayyad Caliphate for consensual sex. 138 The ‘Mughirah vs. state’ case decided by Umar bin Khattab’s court had made this law redundant.

The crime of theft carried the punishment of amputation of a hand. Again, we hear of very few actual cases, if any. Mostly the punishment was topic of social conversation and was proverbial. 139

Alcohol drinking carried the punishment of flogging. 140 Still, we find rare instances where a drinker was punished in reality. Probably, the pattern and style of alcohol drinking explains it. A successful judgment needed two free Muslim male eyewitnesses of unquestionable character. The presence of such ‘angels’ in a gathering of alcohol drinkers in such a large number was impossible.

The main aim of flogging as a punishment remained to inflict insult rather than to inflict injury.141 For political rivals, who faced the charges of being miscreants, flogging no longer remained gentle. Its aim was to cause bodily harm, even if a person dies in the process. Obviously, such death was not considered capital punishment. It was rather accidental death as a consequence of another prescribed punishment. This concept appeared during the Second Arab Civil War. Amr bin Zubayr was the first to die because of flogging. Amr had flogged supporters of Abdullah bin Zubayr’s rebellion in Medina in his official capacity as police officer. Each of his victims took vengeance on him except two. 142, 143

Each case needed two eyewitnesses. The only exception was the cases of sexual misconduct which needed four witnesses. 144 A contract, like any other legal matter, needed two witnesses. 145

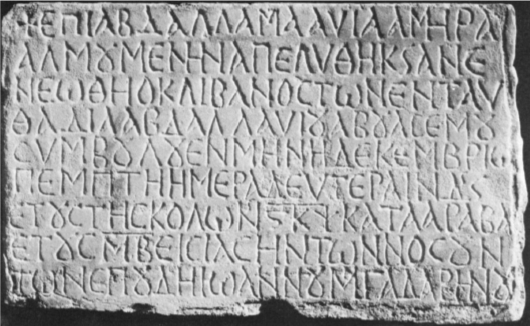

A legal contract written in 663 CE and witnessed by two men. 146

Some details of the court procedure have survived. When Abu Bakr bin Muhammad bin Amr bin Ḥazm of Ansar was governor of Medina, two people brought their civil case in his court. One of them was from the Fihr clan of Quraysh and another was from the Najar clan of Ansar. They had a dispute over the ownership of a piece of land. Abu Bakr granted the land to the Najari. After April 10, 720, when Abu Bakr was dismissed and Abdur Rahman bin Ḍaḥḥāk bin Qays of Quraysh became governor, the Fihri brought the matter up again in Abdur Rahman’s court. The Fihri tried to convince the court of mistrial. The court had to summon the Najari and Abu Bakr. Abu Bakr told the court that he had given the verdict by due diligence and after the deliberations of many days. He had even sent the case for opinion of legal scholars (Mufti) whom the Najari had been given a chance to question. The Najari admitted that he was given the chance to question the legal scholars but claimed that he was not bound to their opinions. Abdur Rahman judged that if the Najari acknowledges he was provided the chance to question the legal scholars, he does not have a right to claim for the land again. Abdur Rahman dismissed the case. 150 So, the governor/judge was non-technical on legal matters. He relied on the legal opinions of professionals to reach a judgement. The judge was solely responsible for the verdict. The judge had a right to pick legal experts of his choice without taking any inputs from the parties to the dispute. One can safely assume that the governor/government paid the legal experts. The plaintiff could argue with the legal experts but their opinions were binding. Interestingly, in the above-mentioned case, the judge belonging to Ansar gave verdict in favour of Ansar, but the judge belonging to Quraysh did not give verdict in favour of the Qurayshi. In this case, both judges based their judgement on the merit of the case.

Details of another court case are sketchy but worth noting. In this particular case, the government of Hisham bin Abdul Malik wished to collect money from the family of Governor Khalid bin Abdullah that the government believed they owed. Khalid’s son Yazid produced a statement under torture that four men of Medina owed him money, which he had paid to them to buy a land in Medina but did not complete the deal. Yazid bin Khalid actually wanted the government to squeeze money out of those four and count it towards repayment from him. Hisham summoned the four to his court where he cross examined them and took their statements under oath. They all denied owing any money to Yazid bin Khalid. Then Hisham sent them to the court of governor Yousuf bin Ibrahim with instructions that Yousuf should summon Yazid bin Khalid in the presence of the four men. Ask the four to reproduce their statement of denial of owing any money in presence of Yazid bin Khalid. Then ask Yazid to provide a proof if he had any to counter their statements. If Yazid fails to provide any proof, ask the four to take an oath to verify the truth of their statements. Governor Yousuf bin Ibrahim followed the instructions. Yazid failed to provide any proof for his claim. The four went to the local mosque along with the involved parties to take oath after the afternoon prayer. 151 Here both parties got ample chance to defend themselves.

Look at the summary of another court case. This was a dispute between the descendants of Husayn and Hasan in Medina about the inheritance of income from an endowment (waqf) property of Ali. Solely, Hasan’s descendants were probably using the income. Abdullah bin Hasan bin Hasan bin Ali represented the Hasan house and Zayd bin Ali bin Husayn bin Ali represented Husayn’s house. Abdullah bin Hasan had the power of attorney from the other Hasan family members to represent them. The case started in the court of Ibrahim bin Hisham, the governor of Medina. The judge constituted a jury of legal experts from both the Ansar and Quraysh factions. The function of the jury was to advise the judge on the legal aspect and not to give a verdict. Abdullah bin Hasan argued that Zayd was a son of an Indian slave girl. In this way, he was not entitled to any inheritance. Zayd argued that being a son from a slave girl does not diminish a person’s rights. Islama’il was a son of a slave girl and he obtained more than a property. Allah made him the forefather of Prophet Muhammad. Abdullah was speechless. The judge ordered the adjournment of the court until the next day so the plaintiff could refine his arguments. The next day both litigators were entangled into a personal mudsling on each other’s mothers. The aim was to establish superiority in descent. Both had a common grandfather, they could argue only about their mothers. One of the Ansar jurist tried to intervene so they would not air their dirty laundry in public. Zayd got irritated and questioned the eligibility of the Ansar jurist to sit on the jury for a case among Quraysh, he being from inferior tribe. The Jurist got offended and claimed that not only he was superior to Zayd but also his father and mother were superior to Zayd’s father and mother. The claim made a Quraysh member of the jury so furious that he walked out saying that it was not bearable to him. The court was held in the mosque in public. The character assassination of each other’s mother by both of them became the talk of the town. Both could tell that the judge was unnecessarily prolonging the case to further amuse the public. They withdrew the case with mutual consent. Then they appealed to the court of Caliph Hisham to hear their dispute. The Supreme Court did not admit their plea, arguing that the matter was subjudice in a provincial court. Both pleaded that the matter was not about only money; it was about interpretation of the law of inheritance. The Supreme Court accepted their appeal after a long delay. 152 We note that the disputing parties had to plead their case themselves. They could not engage attorneys to represent them.

Being a judge in a case under hudd law and punishing a person was not out of danger. Sometimes a later court, presided over by the next governor, ruled that the condemned culprit was actually innocent. In this case, the judge who had imparted the original sentence could be liable for compensation. Compensation in such cases was to undergo the same punishment which the innocent had received.153

The court system definitely took into account the social status of the complainant and the defendant when imparting punishments. Nasr bin Sayyar was the lieutenant governor of Khorasan in 744 CE. He presided over a court case in which the complainant was an envoy of Governor Mansur bin Jumhur of Iraq. He had sent the envoy to Nasr. On his way to Merv, the envoy stayed in Nishapur. There, a government servant who happened to be in charge of coinage (sikak) seized him, beat him and broke his nose. The envoy brought the case of damages to the court. Nasr imparted a fine of twenty thousand dirhams and a set of clothes. Nasr said, “The person who broke your nose is a mawla of mine. He is not a social equal, so that I may take retaliation from him on your behalf. So don’t complain anymore.” 154 This particular court case discloses another feature of the court system of the Umayyad Caliphate. A conflict of interest did not bar the governor/judge from judging the case. The status discrimination can be seen in hadd cases as well. Once, Ali bin Abdullah bin Abbas faced a murder case. He was accused in the court of Caliph Walid by his stepmother of murdering his half-brother. Caliph Walid judged the case in his capacity as governor of Syria. Ali defended himself by claiming that his slaves committed the murder. The Judge imparted a light punishment on Ali by exiling him. He did not establish the fact of who murdered the man. 155 Ali bin Abdullah was a dignitary and close to Caliph Walid.156

Brand new punishments like imprisonment, fines, public insult and amputations of different parts of the body were abound. Capable surgeons supervised amputations because the sentence could not become a capital punishment. 157

A new technique of arresting criminals emerged during the Umayyad Caliphate. It was the arresting and harassing of close family members of an accused if he himself had absconded or was out of reach of law enforcement agencies. In most cases, such family members were released later on when the law enforcing agencies achieved their target. 158

It was possible for the accused to run away from their district of residence to avoid justice and take refuge under the wings of the administrator of another district. The background of an interesting letter, written in April of 710 CE and preserved in Egyptian National Library Cairo, is that a junior administrative officer had given refuge to certain fugitives from the neighboring district in Egypt. The administrative officer of the neighboring district complained about this matter to Governor Sharik. Governor Sharik wrote the letter to the junior administrative officer ordering him to return the fugitives with immediate effect. 159

The concept of vicarious responsibility was present in the Umayyad Caliphate’s legal system. Once, lieutenant governor Nasr bin Sayyar personally compensated an Arab Muslim who was wronged by a mawla of Nasr. 160

Anecdotes of lynching do exist. Just before the end of the Umayyad Caliphate, an angry mob took four political prisoners out of Harran Jail and stoned them to death. One of them was a Patrikios of Armenia by the name of Kūshān. 161

The overall law of the country stemmed from Islam. One of its offshoots was the allowance of non-Muslims to settle their disputes according to their respective religious practices and by their own judges. A papyrus discovered in Egypt brings to light that people clarified at the time of entering into a contract which court system would apply in case of breach. 162

As the Umayyad Caliphate was a huge country and many times the government was too weak to dictate its terms, examples of deviation from the standard practice of justice can be spotted. On one occasion, at least, a Muslim judge presided over a case of a non-Muslim. 163

The mingling of Muslims and non-Muslims became a normal affair in the Umayyad Caliphate after the Second Arab Civil War. Clash of interests between members of the two communities was inevitable. Which court system would decide the case in case a crime took place because of clash between members of two different communities was a tricky question. Apparently, if the accused was Muslim, only an Islamic court dealt with the case. Look at the case of Abdullah bin Awf of Azd. He killed two dihqans of the Durqīt Canal region (near Mada’in) in a bout of rage. His case reached the court of Governor Hajjaj bin Yousuf.164

As rulers were quite powerful, they could commit crime with impunity. A vivid example is murder of Sa’id bin As at the hands of Abdul Malik bin Marwan. When the victims or their families lost hope of any justice, they satisfied themselves by waiting for the Day of Judgement when Allah would provide justice. 165 Actually, waiting until the Day of Judgement for justice was a usual coping mechanism in the case a powerful man committed a crime and went unpunished. Many instances of such behavior are present. 166

Head price

Paying a head price for the wanted men was a norm for the government in Umayyad Caliphate. 167 The wanted could be a criminal or a political opponent. This arrangement made the survival of wanted men difficult.

Jail break

Imprisonment was a standard punishment in the Umayyad Caliphate. Each administrative center had its own dedicated jail. 168 In addition, the government was using small islands as high security prison where only high grade sinners, thieves and disquieters were kept. 169

Jails have their own cultural cosmos. Look at a story of a jailbreak. In 744 CE Nasr bin Sayyar threw his political opponent, Kirmani, in the Merv prison. Kirmani’s supporters in Merv planned a jailbreak. They hired a man from the town of Nasaf at the price he asked. The man widened the aqueduct that took water to the jail citadel. The supporters of Kirmani gave him the date of escape. They sent the message to Kirmani hidden in his food, apparently with the help of the jail staff. Kirmani took his supper with his chaperons. The chaperons were appointed by the supporters of Kirmani to observe any mishandling or any compromise to Kirmani’s safety on the behest of the government. When the chaperons left, Karmani entered into subterranean aqueduct. His supporters were waiting outside with a vacant mule. A serpent wrapped around Karman’s trunk at the level of his abdomen in the aqueduct. However, his companions pulled Kirmani out of the narrowest part of the aqueduct and the serpent could not harm Kirmani. Kirmani rode the mule with his fetters still in his feet. The gang rode to a nearby village where a smith cut loose his fetters. Like any A-class prisoner, Kirmani had the privilege of keeping his personal servant with him in the jail. 170

Public image of dacoits

The people of the Umayyad Caliphate had made a hierarchal ranking of crimes in their minds. Praising Ubaydullah bin Ḥurr, the dacoit who had played havoc in Iraq, Tabari’s source narrates, “He was respectful towards free women and abstained from drinking alcohol.171 Dacoity was a lesser crime than disrespecting a free woman and drinking alcohol. A dacoit was acceptable if he did not commit those very serious crimes.

General law and order

The probability of commission of any given crime is directly proportional to the advantage it imparts to the perpetuator, and is inversely proportional to the disadvantage it imposes to the perpetuator and the chances of being caught. The rule holds valid for all cultures, all countries, all religions and all times. The chances of being caught and the disadvantages of committing a crime drastically decrease during any period of political turmoil. The advantages of committing a crime remain the same. It is not surprising that the crime rate increases during political turmoil.

Ziyad bin Abihi/Abu Sufyan made a speech in front of a gathering on assuming the governorship of Basrah. He reminded the people of all the vices that had sprang up in the society, like an abundance of thieves, burglaries, the abduction of weak women, protecting the criminals, grouping on clan basis etc. According to Ziyad, the Muslims had eradicated these vices. He threatened to root out these vices by harsh punishments. He further elaborated that such crimes were new so new punishments had to be devised for them. He promised good governance and particularly that he would be readily available to hear complains, would provide stipends in time, and would not prolong the expeditions. He said that rulers were ruling over them by the authority (sulṭān) of Allah that He had given them. Therefore, the rulers expected obedience from them in whatever they desire and the rulers owe justice to the people. He reminded the people of Hell and that the worldly pleasures had made them forget the afterworld. 172 An analysis of the speech establishes the kind of crimes that prospered in the Muslim society of the Umayyad Caliphate after the First Arab Civil War. It also gives a hint that such crimes were rare before the First Arab Civil War. It further sheds light on the managerial capabilities of Ziyad. He knew that severe punishment increases the cost of committing a crime but it is not enough. Decreasing the advantage of committing crime by increasing people’s income by legal means and keeping the family members together had adverse effect on crime rate. He also knew that a crime gives worldly pleasure and no matter what the government does, it cannot control crime one hundred percent. Reminding people of the Hell further decreases the advantage a crime provides. He also mentioned two new principles to tackle the law and order situation. Chronologically, both are mentioned the first time in the history of Islam. One, Allah bestows with rule and the ruler is responsible to Allah. People have a duty to obey him without question. The second principle stems from the first. As society changes and the nature of crimes changes, the caliph and his governors have to amend and modify existing laws. They also have to enact brand new laws. They can do it by their own wisdom without seeking inputs from the experts of religious law in this matter.

When the country drowned into the Second Arab Civil War the law and order situation deteriorated again. During this time, somebody successfully snatched the anklets of an elite woman from her very legs without being caught, in the same town – Basrah- where Ziyad had established law and order. 173

Luxuries of life

Arab Muslim elite enjoyed all the material luxuries of life that technological developments had provided. The invading Syrian army over Hejaz had the availability of ice to combat heat. 174 Such luxuries were not heard of in Arabia during pre-Islamic times.

War Cries

Like pre-Islamic times, ‘Allah o Akbar’ was not merely a war cry. It was used on any emotion-laden occasion. When the governor of Basrah had rounded up sons of Ziyad bin Abihi/Abu Sufyan with an intention to kill them Abu Bakrah, their paternal uncle, asked for a delay of one week during which he approached Caliph Mu’awiya bin Abu Sufyan for final reconciliation. Abu Bakrah reached back Basrah with a letter from Mu’awiya. The sympathizers of Ziyad in the town were waiting for him anxiously. When Abu Bakrah returned and dismounted from his conveyance, he proclaimed “Allah o Akbar”. All people replied in response, “Allah o Akbar”. And it was not an occasion of war. 175

Saying so, Allah o Akbar retained its position of single war cry in battles against non-Muslims. This was a kind of the slogan of the military of the Umayyad Caliphate. It did not work well during mutual fights of Muslims. Here they designed new war cries distinct to their particular group. The war cry of the Shi’a Ali, for example, was ‘Yā Manṣūr amit” (ye who have been promised victory, kill). 176

Buttering

Pre-Islamic Arabs were crudes who treated each other almost equally. As they reached the ‘civilized’ areas of Iran and Byzantine Rome, they learned new manners. Ziyad bin Abihi/Abu Sufyan was one day on a trip outside his palace when the belt of his robe became loose. Kathīr bin Shihāb immediately drew a needle that was stuck in his cap, and a thread and mended the belt. Seeing that Ziyad said, ‘thou art a man of discretion; and as such a one should never go without an office.” Saying this, he appointed him governor over a part of Jabal.177

Muru’ah

Pre-Islamic Arab muru’ah survived all political upheavals, mingling, and mixing of cultures. Protection of a guest, for example, was a supreme responsibility of an Arab Muslim wherever he lived.178 Actually, Hani preferred death to abandoning a guaranteed guest. 179 One Medinan family had given refuge to a dissident of Basrah by name of Abu Sawādah. In 713 CE governor of Medina Walid bin Uthman bin Hayan exerted extreme pressure on the population to hand over the dissidents to the government. A foe of the host family brought to the notice of the governor that the family had hidden Abu Sawadah in their house. The host family had vowed to die defending Abu Sawadah. They shifted Abu Sawadah to the house of their brother secretly. The governor sent guards but they did not find Abu Sawadah in the host family’s house. Now the head of the host family, Sa’īd bin ‘Amr, petitioned to the governor that his foe should be tried on the charge of the attempt to frame him in a false court case. The governor granted a punishment of twenty lashes to the foe. Abu Sawadah continued to live with the host family. They prayed salat together. 180

Showing respect to the dignitaries was a normal and expected behavior. On his way to Damascus for rebellion, Yazid bin Walid stopped at Jarūd (a village of Ma’lūla., Yaqut II 65 and Le strange Palestine 463) with seven people. Yazid and his companions wished to buy food from a mawla of ‘Abbād bin Ziyād. The mawla refused to sell anything; rather he offered it free as a hospitality. Therefore, he brought hens, young chickens, honey, clarified butter, and curd, which they ate. 181

Visiting a sick person to say ‘get well soon’ remained as popular as it was in pre-Islamic times. 182

A house had a specific sanctity. Nobody entered into a house without permission. Once Mukhtar went to the dwelling of Islmā’īl bin Kathīr. Mukhtar asked Ismail loudly to come out. He saluted and greeted him, clasped his hands and wished him joy. After that he told him the purpose of visit. 183

Getting off a mount to greet somebody was a way to express respect. It was particularly true for the situations where the pedestrian was actually of lower status than the rider was. Once Caliph Hisham bin Abdul Malik came across Sa’id bin Abdullah bin Walid bin Uthman bin Affan in Medina. Hisham got down his mount and greeted him. 184

Office related etiquette

When Abdul Malik bin Marwan entered into Kufa triumphantly, all and sundry came to visit him and acknowledge his superiority. Dāwīd bin Qaḥdham came with two hundred tribesmen from Bakr bin Wa’il, wearing a chain mail (Aqbiyah Dāwūdiyyah). He sat down with Abdul Malik on his couch and Abdul Malik turned to him to talk. Others apparently sat somewhere else, probably on the mats. After a brief meeting, Abdul Malik rose and everybody present rose with him. Following the two hundred tribesmen with his gaze, Abdul Malik said, “those evildoers! By Allah, had their leader not come to me, not one of them would have given me obedience.” 185 Pre-Islamic Arabs did not have any etiquette and manners about officer and subordinate relationship. Actually, no such relations existed among them. Arab Muslim culture developed such social rules after contact with people of Sasanian Iran and probably with those of Byzantine Rome. They trickled into Arab Muslim culture during the Umayyad rule.

When Abdul Malik wrote an open letter to the people of the cantonments encouraging the soldiers to fight against the Kharijis, Hajjaj made the letter read to the people in mosque loudly. When the reader began, “After a greeting of peace, I praise Allah to you,” Hajjaj asked the reader to stop. He said to the people, “O slaves of the rod! When the Commander of the Faithful gives you a greeting of peace, does no one among you return the greeting? These are the manners of ibn Nihyah! (Former police chief of Basrah). By Allah, I swear I will teach you better manners than these! Start the letter again!” This time, when the reader reached the words “After a greeting of peace,” every one of them without exception responded, “And upon the Commander of Faithful be peace and Allah’s mercy!” 186

The subordinates were expected to call their superiors with certain decorum of respect reserved for that post. Otherwise the obedience of the subordinate was questionable. 187 If somebody of social standing did not attend a governor regularly, the governor took it as rudeness on his part. 188

Such etiquette had a wider application. Mu’awiya bin Ḥudayj had played a radical role in establishing authority of Mu’awiya bin Abu Sufyan in Egypt. Mu’awiya bin Hudayj visited Damascus to meet Caliph Mu’awiya. That day the city of Damascus was decorated like a bride and booths of sweat basil were set up in the streets. 189

When Hisham bin Abdul Malik had made up his mind to dismiss Khalid bin Abdullah al Qasri from the office of governor of Iraq, he started looking for excuse. One day, Amr bin Sa’id bin As went to see Khalid bin Abdullah. Khalid insulted Amr in public. Amr complained to Hisham about Khalid’s behavior. Hisham wrote a tough letter to Khalid, full of swearing words, and asked Khalid to go to Amr’s house on foot along with his servants and apologize from him about his behavior. At the same time, Hisham wrote a letter to Amr, acknowledging of his blood relations with the caliph and encouraging Amr to ask anything from the caliph. In that letter he told Amr that it was at his discretion if he forgives Khalid and restores him on his position of governor or dismisses him. 190

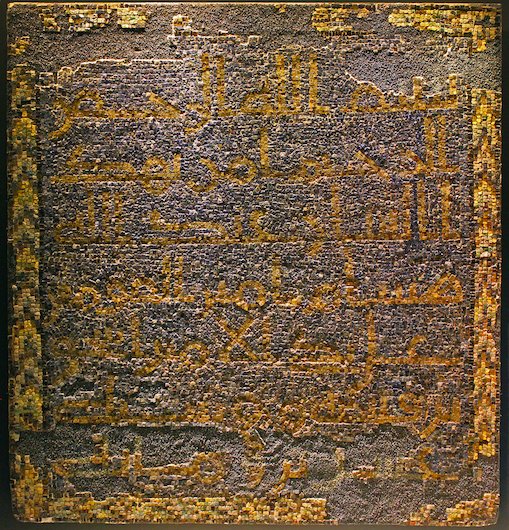

Regalia of the caliph

We keep hearing of a seal as regalia of the Caliph. A postal rider is said to have brought the staff and the ring of the office to Hisham bin Abdul Malik at his holiday home in Zaytūnah. The rider was the official messenger to break the news of the death of Yazid II, and salute Hisham as the next Caliph. 191 A number of seals from the Umayyad time are present in private collections and museums all over the world. Their study is still in rudimentary phase. One thing is sure. All official letters were rolled and the ends were sealed with clay. Official seal was stamped on the clay. 192 Each official, including the governors and the caliph, had his own seal. A seal belonging to the state, rather than a person, is still to be discovered. Probably the incoming caliph got the official seal of outgoing caliph, and he in turn, discarded the old seal. The staff, however, could be a symbol of the state that symbolized transfer of authority. We no longer hear of the robe that a Rashidun Caliph used to wear.

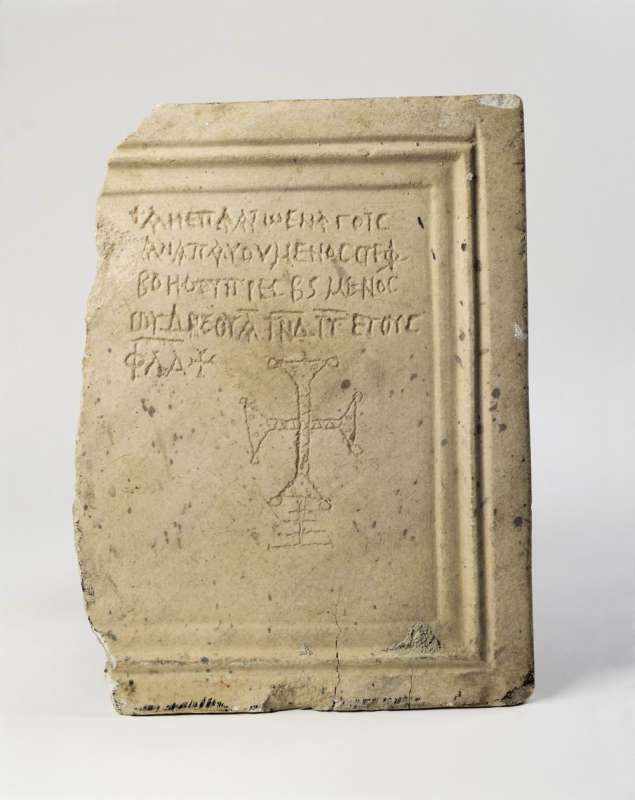

A signet ring seal of the caliph. 749 CE.193

Loyalty a high valued gesture

When rebels attacked Qutayba bin Muslim with the intention to kill him, a person trying to save him was from Bakr bin Wa’il. Qutayba asked him to save his own life. He answered, “How miserable a repayment, in that case, for you gave me bread to eat and soft clothes to wear.” 194 The society attached high value to loyalty.

Nonverbal communication

Some gestures become equivalent to verbal communication. It happens in each culture. Putting a finger on mouth was a gesture of tacit request for others to keep quiet. 195 Seizing feet of some body was ultimate gesture to ask for forgiveness. 196 A nonverbal gesture becomes equal to spoken words only when it has widespread recognition.

Sometimes the communication was verbal but the implied meanings were different from the expressed ones. The listeners understood it well. We know people used to express false anger on a subordinate to satisfy a business client. 197

Animal symbolism