Sulayman becomes caliph

Walid didn’t get enough time to officially amend the will of his father regarding Sulayman. Sulayman bin Abdul Malik proclaimed himself caliph the same day Walid died.1, 2 He did not even bother to travel to Damascus for a formal ceremony. He proclaimed himself caliph in Ramallah where he resided. He was visibly in a hurry. 3 If few prominent figures of the country would have pledged allegiance to Abdul Aziz bin Walid as caliph, Sulayman would have been in trouble. Generally, people hated renouncing their oath because it was a religious misconduct in their belief system. 4

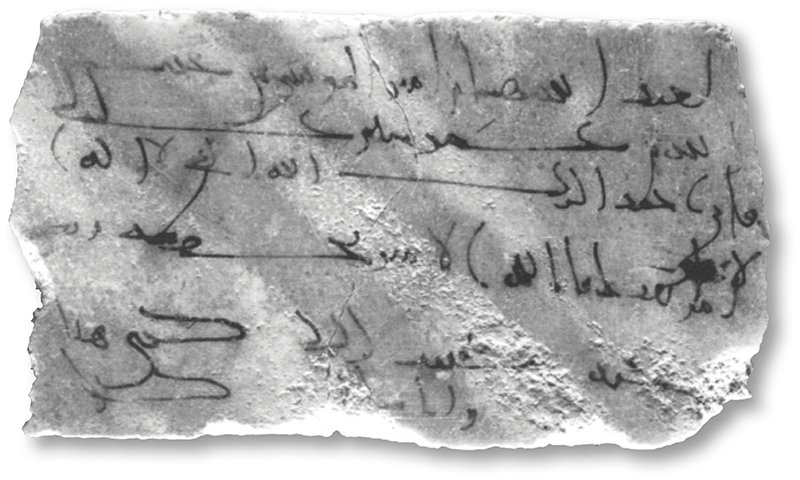

An earthen bowl with Sulayman’s name.5

Sulayman’s retribution against Walid’s governors

The first administrative action Sulayman took after gaining power was to torment all those who had served as a governor during Walid’s government. Yazid bin Abu Muslim was ad hoc governor of Iraq designated by Hajjaj at his death. Sulayman didn’t confirm him in the office. Rather he brought in Yazid bin Muhallab, the sacked lieutenant governor of Khorasan, as governor of Iraq. At the same time, he appointed Ṣāliḥ bin Abdur Rahman, a person afflicted by Hajjaj, as financial secretary of the province. Sulayman ordered Salih, to arrest and torture the family of Hajjaj. 6 Musa bin Nusayr was visiting the capital to deliver the prized booty of Spain and to amass praises at the time of Walid’s death. Sulayman dismissed him and accused him of pilferage and demanded hundred thousand Dirhams from him. Musa could get rid of the trap only on interference of Yazid bin Muhallab.7, 8

Walid not only dismissed the governors of Medina and Mecca but also flogged them and shaved their heads and beards, apparently under a number of hudd punishments, but actually to insult them.9

The only governor of Walid who did not face the vindication was Qurrah bin Sharik, the governor of Egypt. He was lucky to die a few months before Walid. 10

The case of Qutaybah bin Muslim needs special mention. Qutayba was one hundred percent sure that Sulayman would dismiss him and would bring in Yazid bin Muhallab to decide his fate. He reminded Sulayman that he was the most capable officer of the Umayyad Caliphate in the border region of Khorasan and that his name was a guarantee of security in Central Asia. He also requested Sulayman to give him a chance to serve Sulayman’s government loyally as he had done to Walid and Abdul Malik. Qutayba’s letter to Sulayman contained an occult threat that he was in a position to defy the orders of the central government in case of dismissal. Sulayman was, it appears, in limbo. The impatient Qutayba decided to flout preemptively before he received a dismissal letter. He shifted the military under his command to Bukhara under the pretext of a campaign. There he announced his real intentions. He had only regiments belonging to Kufa and Basrah divisions under his command. The ‘Syrian troops’ were not under his command. Common soldiers foresaw a fight against the ‘Syrian troops’ in case the matter lingers on. They were not in a mood to lose their lives for the sake of Qutayba. They simply refused to obey Qutayba. When Qutayba pushed them to obey his commands showing them anger and threats, they turned against him. They not only murdered Qutayba but his whole family. 11, 12

Sources don’t articulate clearly Sulayman’s reasons for sacking the governors. The actions speak for themselves. Sulayman was avenging their opposition to his candidacy. Being governor in the Umayyad Caliphate became a dangerous job. Not only this, each and every governor was, from now onwards, very clear in his mind that his governorship would end with the death of the caliph. The same applied to all subordinates to the lowest level. Each one’s job became subject to the life of his superior. On the flip side, the events of Khorasan proved beyond doubt that fear of the central government of a governor growing powerful enough to challenge the authority was real.

Developments in Khorasan

The murder of Qutayba had left Khorasan without any lieutenant governor. Wakī’ bin Ḥassān, the killer of Qutayba had become self-appointed administrator of the district. In his earliest convenience, Sulayman added Khorasan to the domain of his governor of Iraq, Yazid bin Muhallab, in late summer of 715 CE. 13 Yazid bin Muhallab was under pressure to outperform Qutayba to prove himself.

Gorgan was the most difficult to reach region in Khorasan. This, and its neighboring Tabaristan, had never come under permanent yoke of the Umayyad Caliphate. After their surrender during the first phase of Futuhul Buldan, they were non-compliant in payment of their taxes dues to the central government. They used to pay whatever they deemed reasonable, and many a times didn’t pay a dime. After the final subjugation of many principalities in the region, like Kabul, Tukharistan and Balkh, it was imperative for the Umayyad Caliphate to tame Gorgan and Tabaristan. Yazid bin Muhallab accomplished it in the summer campaigns of 716 and 717 CE. Yazid penetrated the impassable mountains with thirty thousand soldiers. Sul, the Turkish prince of Gorgan fled to an island in Caspian Sea and could not be defeated to the extent of being ousted from power. He, however, saved his life and domain by signing a long lasting treaty to pay taxes in time and in amount assessed by the Umayyad Caliphate. 14, 15

Now it was turn of Ispahbadh of Tabaristan, a Turk by ethnicity. Yazid turned his forces against him in a decisive way. The Ispabadh called help from the neighboring principalities of Daylam and Jīlān. The combined forces got defeated on rolling hills of Tabaristan. Ispabadh agreed to pay taxes in time and whatever Umayyad Caliphate assessed. 16

Last attempt on Constantinople

During previous decade the Umayyad Caliphate had expanded in all directions except sub Saharan Africa and Byzantine Rome. By the time Sulayman took office, first Islamic century was drawing towards its end. Rumors were circulating that Islam shall get dominance all over the world before end of first century. 17 Each ruler of the Umayyad Caliphate wished to be remembered as the one who accomplished final dominance of Islam by annihilating Byzantine Rome from the face of earth. Preparations for the full scale assault on Constantinople with all the might of a big empire had started in summer of 714 CE, when Maslamah bin Abdul Malik had led the summer campaign of Umayyad Caliphate against Byzantine Rome. 18 Maslamah had penetrated only up to Galatia, which was a routine, but somehow Emperor Anastasios had got intelligence that the Umayyad Caliphate was preparing for a bigger invasion by land and by sea. 19, 20, 21 Anastasios remained confident and appointed Leo, the most competent man with political skills available in the empire, as a general to tackle the anticipated attack. 22 The Emperor then, sent his envoy Daniel of Sinope to Walid bin Abdul Malik’s office to negotiate any possible de-escalation. Part of Daniel’s responsibility was to assess the military preparations of the Umayyad Caliphate while he was in Damascus. Daniel reported back to Emperor Anastasios that a great expedition by land and sea was looming against the imperial city. The emperor ordered that everybody in the city would stock provisions for at least three years. Those who cannot afford doing this should evacuate the city. At the same time Emperor Anastasios started large scale defensive preparations. He ordered the building of warships, sails, and Greek fire carrying biremes. The land and sea walls of the city got renovated. All gates of the city got installed with arrow shooting engines, stone throwing engines, and catapults. The city stockpiled as much produce in the imperial granaries as they could. 23 The Umayyad Caliphate was yet fine tuning its offensive preparations when Walid died and the golden chance to be immortal in the history of Islam came into Sulayman’s lap. Sulayman himself moved out of comforts of his palace in Damascus to Dābiq, a military depot in vicinity of Qinnasrin, to supervise the preparations personally. 24, 25.

The legendary Theodosian Walls.26Alexander Van Millingen, Byzantine Constantinople: The Walls of the City and Adjoining Historical Sites, (London: John Murray, 1899), Pl. facing p 46.[/notes]

Emperor Anastasios was optimistic that he would be able to defeat the Umayyad Caliphate militarily. Contrary to his optimism, his country was far from being politically stable. When news reached the ears of Anastasios that numerous warships had left naval bases of Umayyad Caliphate from Alexandria to the ports of Lebanon, and that they would first sojourn in Cyprus to collect wood, Anastasios came into action. He sent his warships to Rhodes to make it a naval base and ordered his army division stationed in the province of Opsikion to join the navy at Rhodes. The plan was that the combined army and navy, would sail to Lebanon and burn its timber, which was the raw material of warships, and would capture whatever military equipment it finds. The soldiers of Byzantine Rome were not eager to carry out the orders. On their way to Lebanon, they mutinied, killed their commander, elected a certain Theodosius as their leader. This Theodosius was an obscure tax collector. The rebels turned their ships back to Constantinople. Emperor Anastasios did not have power to withstand the rebels. After a ‘peak-a-boo’ type of battle between the supporters of Theodosius and Emperor Anastasios for six months, the rebel forces entered into Constantinople. They proclaimed Theodosius emperor and Anastasios resigned. 27, 28

The Umayyad Caliphate attacked Byzantine Rome with its full vigour in late summer of 716 CE, utilizing hundred thousand Syrian Troops. 29 Maslamah bin Abdul Malik, the overall general of the campaign, marched slowly with heavy equipment. 30 He had sent his navy under the command of Umar bin Hubayra and his lightly armed cavalry under the command of Sulayman bin Mu’adh in advance. Sulayman, on reaching Ammuriya, entered into negotiations with General Leo, the commander of the Anatolian division of Byzantine Rome. 31, 32 Leo had royal ambitions and decided to play a double game.33 Representatives of the Umayyad Caliphate offered him a nominal emperorship of Byzantine Rome, provided he chased Emperor Theodosius out of Constantinople. Leo accepted the offer. Simultaneously, General Leo reassured the nervous subjects of Byzantine Rome that the Saracens won’t be able to destroy the Christians through him. Probably Maslamah expected to tear the political fabric of Byzantine Rome by this move before his forces lay a siege against Constantinople. Maslama ordered his military to refrain from harming anyone in the province of Leo to build confidence. The naval ships of Umayyad Caliphate docked at Cilicia and the army camped at Pergamon to winter and to give Leo enough time for action. Leo secured support of General Artavasdos, the commander of Armenian division of Byzantine army. He declared that Emperor Theodosius was unconstitutional and generals Leo and Artavasdos won’t recognize him. 34, 35

In the fall of 716 CE Leo marched on Constantinople, and expelled Emperor Thoedosius out of office with the help of his men. Leo declared himself Emperor and accommodated General Artavasdos by making him his son in law. Immediately after gaining power in Constantinople, Leo showed indifference to Maslamah. Only then Maslamah could figure out that Leo had dodged him. 36, 37 In his fury, Maslamah set his military in motion. At the same time he wrote to caliph Sulayman for reinforcements. The army of the Umayyad Caliphate crossed the Dardanelles Strait from Abydos, and rode through Thrace to Constantinople. On August 15, 717 CE, Maslamah’s army blocked access to Constantinople from land. It dug a ditch along all the land wall of the town and built a wall of mortar by the side of the ditch. Further, it devastated many towns of Thrace to cut off any possible supply to town.38, 39. As planned, the army built wooden houses to live in, and started cultivation around Constantinople to grow food. 40 On September 1, 717 CE the naval fleet of the Umayyad Caliphate was in the area. After the initial failure to anchor on the shores of Constantinople, the fleet could anchor at four different harbors on the European and Asian sides of the Bosporus. They were a total of eighteen hundred vessels including front-line ships, armed merchantmen, and warships. Some of the ships were so heavy with their load that they could not reach the coast and remained in the deep sea. Each of them needed about twenty armed merchantmen for protection with each merchantman staffed with one thousand warriors. Maslama had a plan to bring the warships to forward positions on a windless day so they could be anchored besides seawalls of the city to complete the blockade. This move would have limited Byzantine capacity to use Greek Fire. Emperor Leo’s only hope was an opening from the sea. He swiftly sent the ships equipped to deliver Greek Fire from the citadel, before Maslama could bring his ships near the city walls. They set ablaze the fleet of the Umayyad Caliphate within moments. Wrecks of some of them, still burning, smashed into the sea wall, while others sank in the deep with all men, and still others, flaming furiously went as far off as islands about twenty-five kilometers away. All plans of the Umayyad Caliphate shattered. The wonders of the Greek Fire boosted moral of nervous city dwellers. The Umayyad Caliphate’s navy still had an option to come near the city’s sea wall by entering into Golden Horn. Emperor Leo stretched a chain on the mouth of Golden Horn the same night. Frustrated, the surviving ships of the navy took shelter in bay of Sosthenios. The sea was now open for the residents of Constantinople for fishing. 41, 42 The war was practically over. Now it was only stubbornness on the part of the Umayyad Caliphate to linger on. The caliph had taken a wow that he won’t leave the hardships of Dabiq until the army enters Constantinople.43

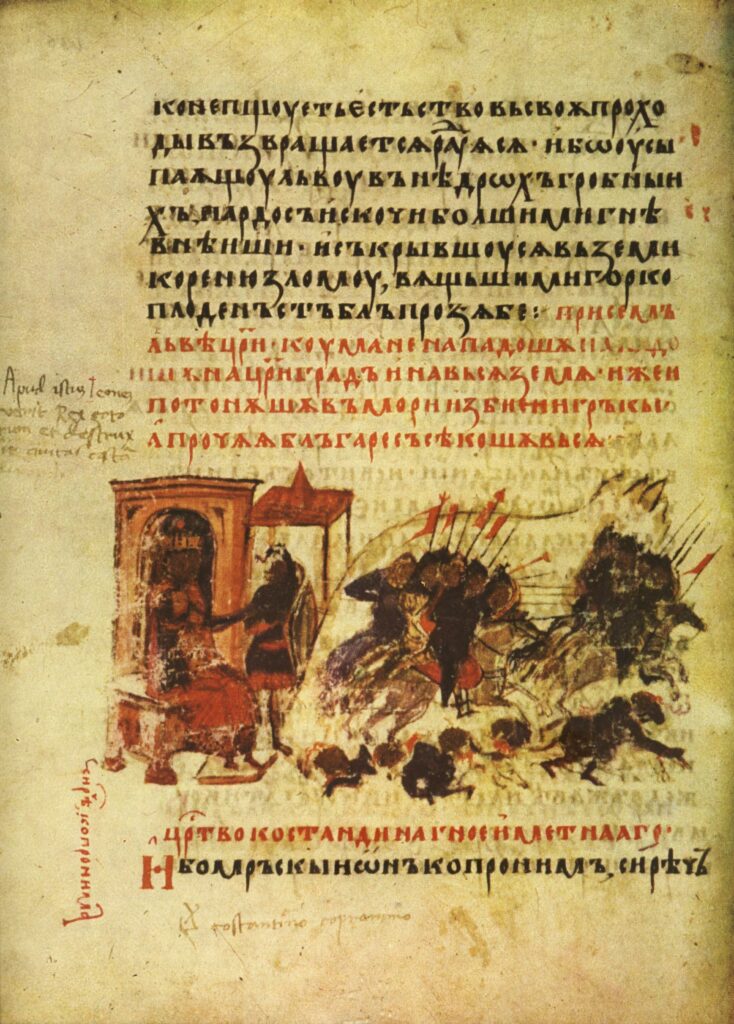

Disastrous second siege of Constantinople: a 14th century miniature.44

Some battalions of the Umayyad Caliphate were still stationed on the Asian land opposite Constantinople. The Umayyad Caliphate had organized a fifteen hundred kilometer long supply chain from Syria for logistic needs of this force. To their surprise, the chain didn’t work well and heaps of grains gathered for the army got rotten in the deserts. 46 The Umayyad Caliphate strived hard to restore this supply route with failure. 47 The conditions of soldiers in Asia were not entirely different from those in Europe. Emperor Leo sent ambush parties to harass them. Their retreat from the shores of Bosporus made fishing for people of Constantinople safer. Constantinople got everything, food and water. On the other hand, the famine stricken army of the Umayyad Caliphate got compelled to eat its dead animals, horses, camels, and asses. The rumors were ripe in the town that they were even eating their own dead men and their own dung. Infectious epidemics spread in their camp killing many more. 48

Umayyad Caliphate had learned its lesson. Co-operation from individual traitors is not a guarantee of defeating a country. No army can defeat a country unless a portion of population supports the invasion, or at least is neutral towards it. And that the Christian power cannot be annihilated only by military means. 49

Sulayman’s place in history

Before we proceed further, let’s be familiar with Sulayman’s impact on Muslim society. Ya’qubi claims that behavior of the subjects in an Islamic country is always a mirror image of the behavior of the caliph. 50 Tabari presents similar concepts and further elaborates his point by telling us, “Then there took charge Sulayman, who was an enthusiast for sexual intercourse and food, and people took to asking one another about coupling and slave girls”51 We don’t hear of widespread undocumented sexual promiscuity during the Umayyad Caliphate. Probably what Tabari is reporting is frequent buying and selling of slave-girls just for the sake of sexual intercourse, rather than for procurement. If we believe in Tabari’s report, the caliph himself suffered from the ailment.

Power changes hands

Sulayman died unexpectedly on October 8, 717 CE at a young age of forty three.52, 53, 54 The cause of his death is not known. Islamic sources report him being over eater and never satisfied with eating. 55 He might not be in good shape of health. The shock of failure at Constantinople might have depressed him. He had nominated his son Ayyub as heir apparent after coming to power. By chance Ayyub died before Sulayman.56 Sulayman’s other sons were either minor or away at Constantinople. His paternal cousin Umar bin Abdul Aziz was present in the camp. He had good relations with pious Muslims. One of them Rajā’ bin Ḥaywa, who attended Sulayman during the death process. He convinced Sulayman to appoint his cousin Umar bin Abdul Aziz as the next caliph. Sulayman willed for his brother, Yazid, after Umar just to bring the power back to Abdul Malik’s house. 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62

Disgraced withdrawal of the military from Constantinople

The most crucial issue for Umar bin Abdul Aziz was the siege of Constantinople. Sulayman had died just before the first winter of the siege. He was aware of the impasse but was unable to send any reinforcements due to harsh winter.63 All attempted reinforcements went under the supervision of Umar bin Abdul Aziz. 64 Probably Umar bin Abdul Aziz was still under illusion that he could be the lucky immortal in the history of Islam. He kept sending reinforcements of clothes, food and money throughout summer of 718 CE. 65 Nothing worked. Another risky winter was approaching. A reluctant Umar bin Abdul Aziz ordered pull out on August 15, 718 CE. Only five hundred horses were enough to bring the surviving army back. Those who were returning by sea met another disaster. A furious storm fell on them when they were in Aegean Sea. Most of them drowned. Those who managed to reach the shore got seized into slavery by elated people of Constantinople. Those who reached back to tell the tale could be counted on fingers.66, 67

Fiscal and administrative reforms of Umar bin Abdul Aziz

The Umar bin Abdul Aziz government had inherited the siege of Constantinople. It had to do something for it. Its undivided attention, however, was on internal affairs. Umar bin Abdul Aziz government survived only two and a half year. During its short tenure it initiated tremendous economic and administrative reforms. Possibly Umar bin Abdul Aziz had realized before coming to power that the country had accumulated numerous domestic problems and that it could not be run indefinitely the way it was being run. Umar bin Abdul Aziz staunchly believed in strength of political institutions. 68 His concept of a successful government was that of flawless economy and inclusivity. It was opposite to that of Mu’awiya I and Abdul Malik which was centralization of power and exclusivity. Most of the surviving evidence of Umar bin Abdul Aziz’s reforms is from Khorasan background. Still, it is justifiable to suppose that such reforms had a wider canvas.

Since Abdul Malik’s administrative and fiscal reforms the provincial governors were expected to collect a certain amount of tax and deliver it to the central government. The central government definitely guided them with tax law. Still, the focus of the central government was on prescribing them the tax amount and not on supervising their adherence to tax law. The central government was happy to overlook any deviation from the prescribed tax collection guidelines on the part of provincial governors provided they submitted the desired tax amount. Furthermore, all administrative levels worked on commission style remuneration. Each administrative level had a right to keep the surplus of what was deemed to be sent to the central government. Resultantly the provinces gradually started raising taxes by hook or by crook. The centralized power in caliph’s hands shaped the government spending policy. Islamic historical sources continue to term all kind of government spending as ‘ata’ (stipends).69 However, the meaning of ‘ata’ was quiet different in the second decade of the eighth century from what it used to be by end of the seventh century. Spending the tax funds in the form of ‘ata’ was at the caliph’s discretion. He obliged his family members, relatives and well-wishers and those he wished to impress upon more than anybody else. A similar government spending pattern existed at the province and district levels. 70 A quarter of a century of such taxation and spending policy created side effects. The total tax burden on general population increased. The formula of tax calculation became unpredictable for a common man. The net flow of money became uni-directional, from the districts to the central government, and from common man to the high ranking government officials, including the caliph. Widespread discontent was inevitable. After a long while, we hear that the Kharijis raised their head again during Umar bin Abdul Aziz’s reign. He had to crush them militarily.71, 72 The people of Khorasan were so disappointed with the government performance that an open rebellion was imminent. 73

The central government had no choice but to attend the matters at home before they get out of hand and to halt the border expansion for now. The Umar bin Abdul Aziz government strived to make the governors abide by the taxation rules. 74 It forbade all officials from receiving the pricy gifts which they used to receive at Nawroz and Mirjan.75 It hit at the knuckles of those governors who were still taxing jiziya from newly converted Muslims.76

The bottom level lieutenant governors had judicial powers. They used them to collect taxes. Umar bin Abdul Aziz government ordered them to demand tax from the peasants gently and not to ruffle them. Furthermore, the Umar bin Abdul Aziz government forbade carrying out punishments awarded by local courts, like cutting off hand of a thief or crucifying anybody, without judicial review from the court of caliph. 77

The central government halted the endless flow of tax money from the provinces towards the central government. The Umar bin Abdul Aziz government ordered the provincial governors to spend most of the tax money in the same district which had contributed towards it. 78

The Umar bin Abdul Aziz government made some changes in the spending policy of the central government as well. It allocated funds for spending on public welfare independent of the caliph’s discretionary powers. The aim was to recycle the collected tax. The government promised to pay one hundred Dirhams to women with children towards their expense for Hajj if any intended to perform it. 79 It started some kind of child support subsidy after weaning. (When parents had to provide the child food). 80 The government devised a disability grant of fifty dirhams for all chronically sick people in the province of Basrah. In addition, abject poor of Basrah got government assistance of three dirhams each. 81

No government can afford annoying the military, especially at the time of distasteful reforms in the country. The Umar bin Abdul Aziz government was under pressure to raise the salary of soldiers. It gave a raise of ten dirhams per person to the Syrian troops only. It did not raise anything for the other military divisions. 82 The Syrian troops might have considered this ‘peanuts’. Umar bin Abdul Aziz is on record telling them that they should not expect more.83 However, the government introduced some kind of lottery scheme in all divisions of military by which the winners of the lottery got a family allowance on top of their salary. It had two tiers, one of hundred dirhams and the other of forty dirhams.84

After enduring extreme tyranny, the opposition got some relief during the Umar bin Abdul Aziz government. As a first confidence building measure, Umar bin Abdul Aziz repudiated the deeds committed by members of his family, which he branded as acts of injustice.85 He banned the cursing of Ali bin Abu Talib from the pulpits. 86, 87 He gave some financial support to Banu Hashim. Ya’qubi reports that Umar bin Abdul Aziz granted fifth (khums) to Banu Hashim. 88 It could be a token money got as booty from the raids. Umar bin Abdul Aziz restored Fadak to descendants of Fatima. He had inherited it from his father Abdul Aziz, who had inherited it from Marwan. Mu’awiya had granted it to Marwan. 89

Banu Hashim were not the only one to get exclusive treatment at the hands of Umar bin Abdul Aziz. Other political groups received a softened stand. Ibrahim bin Muhammad bin Talha bin Ubaydullah, for example, got his confiscated property back. 90 He was a prominent member of the ‘Meccan Alliance.’

Khorasan – a trouble child

The clamorous setting of the country in which Umar bin Abdul Aziz was operating, and which compelled him to introduce reforms, is obvious from the news of Khorasan. Immediately after taking office, Umar bin Abdul Aziz appointed Jarrāḥ bin Abdullah, a man of his own liking, over Khorasan as lieutenant governor. The newly appointed lieutenant governor sent back his first report of situational analysis. The report was gloomy from the Umayyad Caliphate’s perspective. The essence of the report was that ‘the people at Khorasan were at the verge of rebellion. They wanted to withhold what they owe to Allah (meaning tax). Only a sword and whip would control them.’ Umar got upset. He wrote back to use only whips and not swords, and even use whips after due judicial process. 91

The question is why was Khorasan so troublesome? And the answer is that Khorasan was special. It was different from others.

The Arab’s internal economic migration started again after a lull during the Second Arab Civil War. 92 The general direction of the flow of immigrants was from Iraq towards the eastern districts of the Umayyad Caliphate. 93 Khorasan proved to be particularly attractive to economic immigrants. Tabari mentions the presence of two small towns in Khorasan as early as 696 CE, whose whole population consisted of Arabs. One was near Merv by the name of Bāsān. Only the Arabs of Banu Nasr inhabited it. The other was also nearby, by the name of Būyanah. Solely the Tai Arabs inhabited it. 94, 9596 The Arab population in Khorasan was disproportionately bigger than any other eastern district of the Umayyad Caliphate. 97 We don’t know exact reasons for Khorasan being the first choice of the Arab economic immigrants. It could be the remoteness of the district. People might be running away from the oversight of authorities. It could be a higher chance of getting seasonal work in the army and getting rich with booty. Khorasan was the most active region of cross border raids since end of the First Arab Civil War. It could be easy availability of virgin lands. Whatever the reason, the Arab settlers of Khorasan were subject to local Dihqan tax collectors. Khorasan did not get fully assimilated in the Umayyad Caliphate until Qutayba’s campaigns of the 710s. Sulh agreements between different agents of the Umayyad Caliphate and the local lords were about payment of lump sums. Role of agents of Umayyad Caliphate was to make sure local lords make timely payments and in full. What formula the local lords used to collect tax in their respective jurisdictions was not a headache of the agents of the Umayyad Caliphate. The Arab dwellers of Khorasan did not get lower tax rates, like the Arab Muslims dwelling in other parts of the country. This was the first clash of interests that made Khorasan special. 98

Khorasan was ‘the hen that laid golden egg’ in the eyes of the rulers of the Umayyad Caliphate. This impression could have been created by easy success of raiding expeditions and their favourable returns since the time of Mu’awiya. Each succeeding caliph expected the lieutenant governor of Khorasan to send back huge treasures. If any lieutenant governor failed to yield results he was dismissed in one or two seasons. 99 Decades of plundering and looting would have brought economic recession in the region. Further, the transfer of much of the looted goods to Iraq and Syria would have depleted the region of investable capital. All reasons of economic downturn were present in Khorasan.

Economic downturn gives birth to all sorts of chauvinisms. “Humph! My son did not get job due to color of his skin,” the argument goes. No wonder Arabs of Khorasan harbored worst tribal chauvinism. Conflicting tribal groups among the Arabs in Khorasan were those of Mudar and Yamen. There was no political division on regional lines among Arab tribes during pre-Islamic times. Neither there was any during first phase of Futuhul Buldan. The stressful events of the First Arab Civil War gave birth to the new geography based classification of the Arabs. 100 The tribal people of Hijaz used to call themselves Mudar in pre-Islamic times. The tribal groups living in the south used to call themselves Yamen. The tribes of northeastern part of the Arabian Peninsula were Rabi’ah. The Rabi’ah tribes had joined hands with Mudar to invade Iraq and Iran during the first phase of Futuhul Buldan. It was they who got houses in Basrah at the time of its founding. Tabari informs that the Azd Oman tribe of the south immigrated to Basrah later on for economic reasons. They did not get houses inside Basrah and had to be content with camping on the outskirts of the town. When the Second Arab Civil War was in its credible, tribalism raised its head everywhere. Rabi’ah were numerically small in Basrah. They felt threatened from Mudar. They made an alliance with the campers of Azd. The Rabi’a-Azad alliance was conveniently called Yamen. Mudar and Yamen fought against each other in Basrah and Khorasan in the Second Arab Civil War until both were satisfied. Generally speaking, tribalism got defeated in the Second Arab Civil War all over the country. Khorasan was special. Tribalism survived in the backdrop of political theatre. It was tribalism which compelled the conscious citizens of Khorasan to appeal to Abdul Malik to send a man of Quraysh as governor.101 Since then, all lieutenant governors of Khorasan, including Muhallab bin Abu Safrah and Qutayba bin Muslim had treaded a cautious path to deal with tribal tendencies in Khorasan.

Khorasan had one more special feature. From its very beginning Islam was more attractive to certain cultures.102 Turks of Khorasan were one of them. Islam had started spreading among them even before Qubayba bin Muslim had assimilated Transoxiana into Umayyad Caliphate.103 Khorasan had a larger proportion of Mawlas as compared to many other ex-Sasanian districts. Increase in numbers of Mawlas was inversely proportional to decrease in numbers of non-Muslim Ahl al Dhimma. The development resulted in contraction of tax base. Now, Khorasan had got a reputation of ‘land of opportunities’. Candidates of Lieutenant governorship preferred it over others. Each succeeding lieutenant governor reached Khorasan to fill his own pockets and at the same time to send lavishly to the central government via provincial government to keep his job.104 Though raids generated main income of district, provincial and central governments, locally collected taxes made a significant portion thereof. In face of increasing population of Mawlas, the lieutenant governors were not inclined towards applying same lower tax rate to them which Arab Muslims enjoyed after full assimilation of Khorasan in Umayyad Caliphate. Arab Muslims had no objection to such taxation policies. The last clash of interests which developed in Khorasan was between Arab settlers and the Mawlas.

Murder of Qutayba bin Muslim broke the dam which had a capability of containing all opposing torrents. Group based hatred became pervasive and endemic in Khorasan after Qutayba’s death. Three groupings were more oppugnant than any other – non-Muslims vs Muslims, Arab Muslims vs Mawla Muslims, and Mudar Arabs vs Yamen Arabs.

Qutayba’s successor, Yazid bin Muhallab, was artless in tackling the tribal sentiments of Arabs. He filled all available lucrative government posts with the people of Mudar at the expense of Yamen.105 This action of his accelerated the pre-existing tribal hatred to the top notch. The situation could still have been handled. Umar bin Abdul Aziz was apt in dismissing Yazid bin Muhallab after coming to power due to his personal disliking for him.106 Jarrah bin Abdullah, Umar bin Abdul Aziz’s pick to govern the troubled district, was even worse than Yazid bin Muhallab. To bring all Arab tribes on one platform, he raised the slogan of Arab nationalism, irking the Mawlas.107 Jarrah bitterly failed to mend the cracks between Yamen and Mudar but he successfully widened the gap between Arabs and the Mawlas.108, 109

Winding up of Futuhul Buldan program

Umar bin Abdul Aziz’s short lived government was too busy on domestic front. It neither had appetite nor energy to seek territorial expansion, which had been a flagship policy of Abdul Malik, Walid and Sulayman’s governments. Winding up of Futuhul Buldan program was not a conscious decision of Umayyad Caliphate. The circumstances dictated it to do so.110

Khorasan gave the first shock to the long cherished concept of territorial expansion in the name of Islam.111 Forces of Umayyad Caliphate operated in Transoxiana to subjugate the non-compliant non-Muslim Turks in first year of Umar bin Abdul Aziz’s reign. Umayyads got a crushing defeat. A disheartened Umar ordered halting any further raids. “Let them be satisfied with the victories that Allah had already granted to them.” Umar declared while halting the Futuhul Buldan program.112 A number of Arab families had settled in Transoxiana. Withdrawal of Umayyad Caliphate forces to the western bank of River Oxus made their safety precarious. Umar advised all of them to evacuate the land because his government was no longer in a position to protect them. They chose to stay on at their own risk.113

Then came the ignominious retreat from Constantinople. Byzantine Rome got so bold that the very next summer in 719 CE it sent its navy ships to Ladhiqiyah, the very heart of Umayyad Caliphate. They took many Muslims in captivity. The weak government of Umar bin Abdul Aziz had to pay ransom for their safe return.114 The development was troublesome for Umar. He ordered strengthening of fortification of Ladhiqiyah.115 Soon after, Umar bin Abdul Aziz personally inspected the fortifications at the border of Syria and Armenia. He ordered abandoning many of them to hinder the potential Byzantine Raids to Umayyad Caliphate.116 Umar bin Abdul Aziz government also reversed the decision of Abdul Malik to raise the tax on people of Cyprus.117 It could be another gesture of détente for Byzantine Rome.

Umayyad Caliphate had been launching regular summer and winter assaults on Anatolia throughout its life. Halting them would have given a wrong signal to the opposite side. Umar bin Abdul Aziz government organized them albeit on lower scale.118

Umayyad Caliphate had teased Khazar Khanate by destroying Bab.119 The Khanate had grown powerful and won’t take it lightly. Counterattack from their side was expected. In 718 CE, when Umar bin Abdul Aziz ruled the Umayyad Caliphate, we hear from Khalifa that Khazars (Turks of Khalifa) attacked Armenia and Azerbaijan. The local border guards easily repulsed the attack. Umayyad Caliphate dug a defensive canal along whole border to prevent future attacks.120 Tabari verifies it. “Turks attacked Azerbaijan killing a group of Muslims and causing serious damage. Umar bin Abdul Aziz sent his general who killed the Turks and only a small number could escape. The general captured fifty of them as prisoners of war” reports Tabari.121 This was the first intrusion of Khazars into Armenia and Azerbaijan since the times of Sasanian Iran.

Umar bin Abdul Aziz government adopted the same policy of nonviolence at the borders of Ifriqiya. We don’t hear of a single raid in that border region during Umar bin Abdul Aziz’s tenure.

Did Umar bin Abdul Aziz flip the official policy?

Umar bin Abdul Aziz is an atypical ruler of the Umayyad Caliphate. Islamic sources join in a chorus to sing his praises. They label him as a torch bearer of justice and reviver of original Islamic practices. Reference to the Book of Allah and Sunnah of the Prophet definitely increased in frequency during his tenure. Official instructions to the governors and generals attained more religious tone.122 The religious leaders softened their antagonistic stand against the central government. A common vision between the caliph and the religious leaders started developing. However, all these changes were in supra structure. We don’t find any change in the foundations. The caliph continued to govern single handed without establishing any consultative institution. The caliph held the same draconian powers which his predecessors had attained. Excellence in religion did not become criteria in appointments of governors or generals. The policy of arrest, extortion and insult of a dismissed governor continued.123 The central government re-confirmed the land grants to members of Umayyad clan, approved by previous governments and kept paying them government handouts, recognizing their higher status in the society.124 The caliph continued to inscribe his name on commemorative plaques of the buildings funded by the central government as a show off.125 So on and so forth.

Then a natural question arises why Umar bin Abdul Aziz government tried to look different? It appears that the descendants of Abdul Malik had attained massive power. Umar bin Abdul Aziz aspired to reduce their influence. One way to achieve the target was to find friends in non-conventional circles – the religious leaders.126 Umar bin Abdul Aziz government’s parleys were only with those religious leaders who were incubated by previous Umayyad governments. Examples are Zuhri and Raja’.

Young death of Umar bin Abdul Aziz

Umar bin Abdul Aziz was only thirty nine years old when he died. A short illness took his life on February 10, 720 CE. Umar bin Abdul Aziz’s fiscal policy was not compatible with further accumulation of wealth in hands of Umayyad house. They were afraid that if things continued in the same direction, one day Umar might confiscate their properties. They were also nervous that if Umar’s parleys with religious leaders cross a limit, power might get out of Umayyad house forever. Umar bin Abdul Aziz himself didn’t shun from expressing that if it was up to him he would nominate a religious leader as his successor. Under these circumstances, it is not surprising that rumors circulated that Umayyads had poisoned Umar bin Abdul Aziz.127, 128

Tomb of Umar bin Abdul Aziz. 129

Place of Umar bin Abdul Aziz in history

Later Muslim generations had a great regard for Umar bin Abdul Aziz. They considered him a replica of Umar bin Khattab and took pride in the fact that he was a maternal grandson of Umar I.130, 131 Unlike his predecessors in Umayyad Caliphate, Umar bin Abdul Aziz presented himself as a down to earth ruler who wished to look like common citizens. Soon after assuming power he abandoned the grand governmental palaces of Damascus and took residence in an ordinary house.132 He revived the idea that being a caliph over Muslims is a burdensome responsibility rather than a prestigious carrier option.133

Umar bin Abdul Aziz’s attire of a devout Muslim could be, anyhow, a political farce. Ya’qubi reports that Umar bin Abdul Aziz adopted the religious propensity later in his life.134 The only surviving statement from opponents of Umar bin Abdul Aziz is that of Yazid bin Muhallab. He labels Umar bin Abdul Aziz as ‘hypocrite’.135 We don’t find anything atypical of Umayyad governors during his work as governor of Medina. His baggage and pomp and show with which he landed in Medina to take a charge were splendid. Thirty camels delivered his luggage to Medina.136 He did have a meeting with prominent Jurists of the town, including ‘Urwah bin Zubayr, Sālim bin Abdullah bin Umar and Abdullah bin Abdullah bin Umar, and reassured them that he would take their inputs in decision making process. He also invited them to inform him about any transgression or injustice on the part of his government.137 However, this could be a routine meeting, a usual for a new governor. None of these Jurists was in opposition to the caliph or the governor.138

A caliph born with silver spoon

Worst negativity of dynastic aristocracy is scarcity of competition for the highest ruling post of the country. People with high mental caliber lay foundation of a dynasty. They usually arise from general cadre and are in touch with reality. They are generally flexible, diplomatic, and cunning. As time passes the forthcoming generations of the ruling family are born with a silver spoon in mouth. The possible heirs are raised in an isolated environment of a palace under the tutelage of a personal trainer. They never have a chance to learn from ‘open university of people.’ They are usually of average mental caliber, not capable of tackling the political, social and economic issues of their time. They get a chance to govern the country only because nobody competed with them for the top slot. Yazid bin Abdul Malik is a typical example of ‘a heir born with silver spoon.’ Yazid bin Abdul Malik (Yazid II) took over the caliphate after death of Umar bin Abdul Aziz according to the will of Sulayman.139 He did not have any clue of the troubles the country was facing and the reasons behind the reforms of his predecessor. His sole perception about his country was that it was created to serve the interests of caliph and his family. Single aim of the young and inexperienced caliph was to provide as much luxury to the caliph and his Umayyad friends as possible.140

Reversal of Umar bin Abdul Aziz’s reforms

Umar bin Abdul Aziz had died prematurely without institutionalizing his reforms. It was simple for anybody to annul them by decree. Yazid bin Abdul Malik government worked sincerely on it for the next four years.

Yazid II government restored the previous taxation and government spending policy. Taxation on vacant lands re-started. The custom of payment of cash or expansive gifts at the time of Nauruz and Mihrajan reinstated. 141 There was nothing which Umar bin Abdul Aziz had introduced and Yazid II didn’t change. 142

Yazid II government took off the olive branch Umar bin Abdul Aziz had offered to the opposition. Instead it presented a bouquet of thorns. Confiscation of their properties restarted.143 Most pronounced was confiscation of Fadak by the government.144

Empty government coffers

The speedy taxation and spending reforms of Umar bin Abdul Aziz must have reduced the government exchequer to a dangerous level. Yazid II government had to face the consequences. Previous governments of Umayyad Caliphate are known to have faced financial constraints. This time it was different. Yazid II government did not have money to spend at time of dire need. His governor of Basrah could pay the soldiers only two dirhams each in the midst of the fighting with an empty promise that they could be paid more only if the central government sends an authorization to do so.145 Even the central government had to quieten the fighting soldiers by mere promise that their stipends would be raised.146

One of the reasons for Yazid II government to revert the fiscal policy of its predecessor could be the urgent need for money. Yazid II government also looked for new sources of tax revenue. In 723 CE it carried out a fresh land survey in Swad. It brought those palm trees and other trees into tax bracket which had been omitted by the previous survey conducted by Umar bin Khattab government.147 Umar bin Abdul Aziz government had barred the torture of outgoing governors, though insulting them had continued. Yazid II government resorted the practice of torture to the extent of killing to extort money from outgoing governors and their officials.148

Rebellion of common people

When Yazid bin Muhallab escaped the Damascus prison after hearing the news of Yazid bin Abdul Malik’s ascension, the former didn’t know that he would be a leader of revolt against the central government. His only moto was to avoid wrath of the new ruler.149 Yazid II ordered his officials in Iraq to hunt down Yazid bin Muhallab. To the surprise of Yazid II, the divisions of both Kufa and Basrah did only halfhearted attempts to grip Yazid bin Muhallab. Yazid bin Muhallab reached Kufa and then Basrah unhindered where the local deputy governor had jailed Yazid bin Muhallab’s brothers to pressurize him. Yazid bin Muhallab demanded release of his brothers, which the deputy governor rejected scornfully. Yazid bin Muhallab hired paid mercenaries to assault the prison where his brothers were imprisoned. After a superficial fight the soldiers loyal to the government conceded defeat and Yazid bin Muhallab could capture Basrah, arrest deputy governor of Basrah and release his brothers from the prison on 31 March 720. Yazid II hastily declared amnesty for Yazid bin Muhallab. Yazid bin Muhallab would have accepted the offer, but to his surprise, people from all walks of life and of different political opinions started gathering around Yazid bin Muhallab. Soldiers of Basran regiment, Kharijis, Qurra, tribal leaders, even some soldiers of Syrian Troops stationed in Basrah were in Yazid bin Muhallab’s camp. The town was in ferment. Encouraged by the scenario, Yazid bin Muhallab formally declared revolt against the central government, promising to enforce the Book of Allah and the Sunnah of the Prophet if he becomes ruler of the country. Very few people, like Hassan al Basri the judge of the town, opposed Yazid bin Muhallab, doubting his intentions to enforce the Book of Allah and the Sunnah of the Prophet, given his well known secular past. Anyhow, Yazid bin Muhallab was swinging high. He appointed his own lieutenant governors over Khuzestan, Fars, Kerman, Bahrain and Sind. The central government could maintain its control over Khorasan. Wasit fell into Yazid bin Muhallab’s hands without any fight. Unrest had spread to kufa, Jazira, Oman, and Khorasan. Yazid bin Muhallab had gathered one twenty thousand supporters. They included soldiers from Jabal and from far off frontiers, volunteers from Medina, as well as those of Kufan regiment who had sneaked out of the town. They all advanced towards Kufa to join hands with kufan division there and to bring whole eastern part of the country under their rule. Yazid II countered their move by promising a raise in the salary of the Kufan division to keep them loyal. The soldiers of Kufan divisions were not kids to be pacified by empty promises. Yazid II had to dispatch two separate regiments of his Syrian Troops. One regiment of four thousand men pacified Jazira and Kufa, restoring grip of the central government over there. Another division of four thousand men proceeded to al ‘Aqr, near Karbala, to halt the rebel forces from entering Kufa, to engage them in war, and to eliminate them. This regiment could accomplish its target in the month of August of 720 CE. As it happens in all situations where a number of people from different political shades crowd together on a short notice, Yazid bin Muhallab’s undisciplined locust sized mob had differences on war strategy. They dispersed in all directions after initial light fighting. The rebels were aware of striking similarities between this rebellion and that led by Abdur Rahman bin Ash’ath two decades ago. The only contrast was the behavior of the leader. Yazid bin Muhallab decided to die a hero’s death fighting on the battlefield on August 22, 720. The Syrian Troops restored order of the central government all over the eastern parts of the country in forthcoming weeks.150, 151, 152, 153 Yazid II government survived due to disorganized condition of the rebellious mob. The rebellion, anyhow, documented the wide spread discontent against the central government. The rebellion also demonstrated the weakening iron grip of the central government. Ordinary rebels could not be prosecuted as had happened after the Rebellion of discontent.

Kharijis raise their head again

Despite Kharijis military defeat, Umar bin Abdul Aziz government was interested in political solution of the issue. It had engaged Shawdhab group of the Kharijis.154 Yazid II government was supposed to do everything opposite to the previous government. It called off the negotiations claiming that the new government would not honour even the memorandum of understanding both parties had produced. Yazid II government sent small battalions of up to two thousand men many a times to contain the Khariji group with failure. It was only after crushing the ‘rebellion of common people’ that Yazid II government could muster ten thousand soldiers to defeat the Kharijis.155 In any case, the Kharijis were going to be a regular feature of political landscape of Umayyad Caliphate from now onwards. The very next year, in July of 721, a small band of Kharijis raised banner of rebellion in Bahrain and instantly took control of Yamama in their hands. They had to be defeated militarily.156

Anarchism in Khorasan

Jarrah bin Abdullah was the last effective lieutenant governor of Khorasan for Umayyad Caliphate.157 When Umar bin Abdul Aziz fired him in April of 719 CE for deviating from taxation policy of government, Umar knew that Khorasan was out of hand. He appointed two relatively unknown men in Jarrah’s stead. One was over military and the other was over finances. Separating the two interdependent bureau of government was the last option available to Umar to pacify the widespread unrest. He wrote an open letter to people of Khorasan that if they get displeased with these two men then ‘seek help from Allah.’158 Yazid II government, on the other hand, didn’t see the things through the lens of Umar bin Abdul Aziz. It was confident that Khorasan could be tamed by a dynamic personality without fixing its social, economic, and political mess.

The next political period in Khorasan is that of frequent hiring and firing of its governors in a hope of finding a ‘Qutayba bin Muslim’, no practical support, either militarily or financially, from the provincial or central government to stabilize the district, high expectations of provincial and central governments to gain net revenue from the district, inability of government to make necessary amendments in the laws governing the district to improve scenario, and failure on the part of government to extend its justice system, financial system, and police protection to all citizens of the district.

Changing whole government apparatus from bottom to top after change of caliph had become a fashion in Umayyad Caliphate. Yazid II government appointed its own governor in Iraq, and that governor had a compulsion to dismiss the two men appointed in Umar bin Abdul Aziz’s time. When the new lieutenant governor of Khorasan, Sa’īd Khudhaynah reached Merv in summer of 720 CE, he found the district unmanageable. Numerous small and large non-Muslim Turk lords had become semi-independent. A wave of apostasy had swept a large population of newly converted Turk Muslims of Soghdia to their previous religions during the last eighteen months.159 The apostatized Turks had abandoned their lands to avoid paying tax. They had joined hands with non-Muslim Turks to form small militias.160 The militias were making harassing raids on Arab settlers and their Iranian mawlas.161 The Arab settlers were totally fractured on tribal lines. If Mudar battalions would co-operate with government to re-establish administration, Yamen battalions would flatly refuse and vice versa. Rather they would hinder the process.162 On top of it, all groups, whether they were Arabs, Iranians, Turks, Muslims, or non-Muslims, would laugh at the governor and ridicule him.

Sa’id Khudhaynah decided to appoint lower level government officials only by consultations of tax payers. Nobody could agree on a single name.163 He re-started raiding to subjugate the disobedient.164 It ended in a stalemate.165

Umayyad Caliphate got compelled to change Sa’id Khudhaynah with two men, one after other. Both proved to be similar to Sa’id Khudhaynah. The maximum they could do was to prevent further disarray in Khorasan.166

Border with Khazar Khanate

Constant scrimmage at the border between Khazar Khanate and Umayyad Caliphate was a normal feature during previous two governments. It was not unilateral and hence, was not in hands of Umayyad Caliphate alone. Sources describe yearly clashes between the two rivals during Yazid II government. None was decisive. Both sides suffered from loss of property and life. Both did not feel need to sit down and settle the differences.167

Byzantine policy under Yazid

Byzantine Rome – Umayyad Caliphate border had the same conditions which prevailed for years. Forces of Umayyad Caliphate crossed the border yearly to protrude into Anatolia, and returned to their base camps. However, the size and ferocity of the campaigns had decreased during the years of Yazid II as compared to those of his predecessors.168

Armenian policy under Yazid

The border between Byzantine Rome and Umayyad Caliphate in Armenia used to be the hottest at one stage. Lately, that part of Armenia which was under control of Umayyad Caliphate had become passive. Border clashes in Armenia, during the tenure of Yazid II, were of similar intensity as were elsewhere between Byzantine Rome and Umayyad Caliphate.169

Ifriqiya under Yazid

Worst setback for Umayyad Caliphate came from Ifriqiya. Like Turks of Khorasan, Islam was popular with Berbers of Ifriqiya from the time of first phase of Futuhul Buldan. The numbers of Mawlas grew exponentially. Somewhere during Caliphate of Sulayman it became practically difficult for Umayyad Caliphate to honor its tax rates for Muslims and non-Muslims. They charged the newly converting Mawlas at the same rate they used to pay when they were Ahl al Dhimma. Complains and discomfort was rife in the region. Umar bin Abdul Aziz’s tax reforms provided Mawlas with a great relief. Cash strapped government of Yazid II tried to revert Umar bin Abdul Aziz reforms. For this purpose, It sent Yazid bin Abu Muslim, who himself was a Mawla but of old generation, as a new lieutenant governor to the district in May of 720 CE. Soon a revolt flared up in general population and in the army. Local politics must have played a part because the dismissed ex-lieutenant governor Muhammad bin Yazid and the jailed ex-lieutenant governor Abdullah bin Musa bin Nusayr were the leaders of the rebels. A Mawla soldier by name of Jarīr assaulted Yazid bin Abu Muslim fatally when he was praying in the grand mosque of Kairouan. The rebels elected Muhammad bin Yazid as their new lieutenant governor. The same time the rebels wrote to caliph Yazid II that their intention was not high treason against the caliph, they simply didn’t want to pay the tax rate imposed upon them. Poor caliph wrote back that he was already concerned with the tax policies in Ifriqiya and whatever the rebels had done was worth accepting. Then he ordered Bishr bin Safwan, his governor over Egypt, to take administration of Ifriqya district in his own hands. Bishr did not touch Muhammad bin Yazid but he sentenced Abdullah bin Musa bin Nusayr to death in murder case of Yazid bin Abu Muslim.170 Umayyad Caliphate could restore its writ over Ifriqyia. Ifriqiya did not behave like Khorasan because center did not have high expectation of revenue from Ifriqiya and hastily took the unpopular policy back. Umar bin Abdul Aziz government had halted the cross border raids in Ifriqiya. Now Forces of Umayyad Caliphate in Ifriqiya started raiding far off islands again.171 Probably they were safer than at other borders and the region needed income.

Defeat in France

Umayyad Caliphate tasted its first defeat in France in 721 CE. After consolidating its rule in Spain, the forces of Umayyad Caliphate were, now, advancing towards France. They had raided border areas of France and, lately, had stationed a permanent garrison at Galia Narbonensis. The people of France felt threatened. Odo of Aquitaine confronted forces of Umayyad Caliphate at Tolosa. Forces of Umayyad Caliphate got routed and its commander Samh., got killed on the battle field.172, 173.

Sudden end of Yazid bin Abdul Malik government

Yazid bin Abdul Malik died of natural causes on January 29, 724 at the age of 37 after ruling for four years.174, 175

Yazid II’s place in history

Each upcoming caliph of Umayyad Caliphate did something which his predecessor had shunned to do. Yazid gave more attention to his sexual partners than to the affairs of government. Ya’qubi blames, “Then came Yazīd bin ‘Abdu al-Malik. He was the first caliph to acquire a singing slave-girl and the first over whose affairs a woman gained control. Ḥabābah, his singing slave-girl, used to appoint and dismiss, set free and imprison, command and forbid.”176

Yazid II holds another record to be the first in history of Islam. Since times of Umayyad Caliphate it was customary for the sitting caliph to lead Hajj. It was a symbol of their authority over religious matters. As the seat of governance moved out of Hijaz, it became practically difficult for the caliphs to go for pilgrimage every year. They used anybody who was governing Hijaz as their proxy. Still each caliph led the Hajj personally at least once as his religious duty. There were exceptions but each had explanation. Abu Bakr did not lead any Hajj during his tenure. Only one Hajj fell during his tenure and he was pre-occupied with Ridda wars. Ali bin Abu Talib did not lead Hajj personally because he remained busy with First Arab Civil War throughout. Yazid bin Mu’awiya did not lead any Hajj because Ka’ba was under control of his rival Abdullah bin Zubayr. The first caliph who did not perform Hajj during his caliphate out of choice was Yazid II. He had led Hajj once in his capacity as heir apparent. Probably he considered that event enough.

Due to his lusty habits, low political IQ, failure to handle internal turmoil, and weak foreign policy, Yazid bin Abdul Malik is an obscure figure in history of early Islam. Today very few Muslims even know his name.

Long stagnant decades

34 years old Hisham bin Abdul Malik was on holiday at his estates of Zaytūniah in Ruṣāfah when news of Yazid II’s death broke out. Within a day he was in capital Damascus to take reign of the vast country into his hands. After taking oath he returned to Rusafah to make it the official residence of caliph.177, 178, 179 Unlike his predecessor, Yazid II, he had some practical experience. He had conducted campaigns against Anatolia.180 He should have better understanding of things as compared to Yazid II. Yet, most characteristic feature of Hisham government is maintenance of status quo. He did not make any effort to reform the political, economic or social system of the country, though it was direly needed. Hisham government was simply continuation of Yazid II government, as far as policies were concerned. On the surface everything appeared to be in control during his long two decades. Under the surface there were torrents of unrest. They say, still air is predictive of a storm. Hisham’s era was still air and the storm came at the end of his era.

Inscription mentioning Hisham bin Abdul Malik. 181

Intrusion in India

The Umar bin Abdul Aziz government had terminated the border expansion and cross border raids.182 Yazid II government was irresolute over the issue.183. Hisham government allowed both of them, provided the risk and expenses were those of the lieutenant governor of the border district and at least some benefits were transferred to the central government. Need for money at the central government appears to be the main stimulus. Probably Hisham had calculated that it won’t cost much to his internally weak country. Umayyad Caliphate had grown so big that the neighboring countries had no chance to get irked and invade it in retaliation.

Umayyad Caliphate had assimilated Sind about a decade ago. Its lieutenant governor Junayd bin Abdur Rahman was a speculator. He picked the cue intelligently how Hisham wanted his borders to be. He took his forces all the way to Kannauj. Results of this campaign are not known to Islamic sources. Then Junayd invaded the land of China and captured one fortress. Still not satisfied, Junayd attacked Kīraj with the help of king Ashandarābīd and compelled its king Rāh to flee. Ultimately he could appoint his tax agents at Marmadh, Mandal, Dahnaj, Burūṣ, Surast, Bīlamān and Māliba.184, 185, 186 Blankinship considers this campaign as a full scale invasion with intention to add land to Umayyad Caliphate.187 However, circumstantial evidence defies this opinion. Umayyad Caliphate was not in a position to occupy foreign lands, even if it wished to do so. Junayd boasted to Hisham of capturing three fifty thousand captives and collecting eighty million dirhams in booty.188 Nonetheless, he did not send even a cent to the center.

Raids on Anatolia

Umar bin Abdul Aziz government had not halted summer and winter raids on Anatolia after retreat from Constantinople in 718 CE. The failure of siege of Constantinople was a purely defensive action of Byzantine Rome. It was still not in any position to effectively keep the raids of Umayyad Caliphate out of its borders. There is not a single year during Hisham’s tenure in which the raids did not take place.189 The reporting of these raids is as brief as those of previous years and as typical as it used to be. Look at reports of Theophanes the Confessor about two separate raids. In one raid he reports, “In this year [1/9/726 – 31/8/727] Hisham’s son Muawiyah attacked Romania, went here and there, and withdrew”.190 In another raid he reports, “At about summer solstice [21 June 727] a body of Saracens attacked Bithynian Nikaia. It had two emirs. Amr went ahead with 15,000 light-armed men to surround the unprepared city, while Muawiyah followed with another 85,000. Even after a long siege and the partial destruction of the walls, they could not enter Nakia’s sacred precinct ……… after the Arabs accumulated a large body of prisoners and booty, they withdrew. [Emperor] Leo boasted that he prevailed over his fellow citizens due to his piety”.191, 192 It appears that Umayyad Caliphate chose different city each time to avoid timely detection. The purpose was, as usual, to loot human and material resources and return. 193 Things were going smoothly from Umayyad Caliphate’s point of view at this border when something unusual happened near the end of Hisham’s tenure. The summer raid of 740 CE was particularly large. Four field commanders of Umayyad Caliphate penetrated into Anatolia in the month of May from four different directions keeping their target secret. Sulayman bin Hisham was the vanguard with ninety thousand men. His aim was to create general fear. Ghamr led ten thousand lightly armed cavalry behind him to swiftly give surprise attack to any target in Anatolia. Behind both of them were Malik and Abdullah bin Husayn Al Baṭṭal with their combined force of twenty thousand lightly armed riders to target Akroinos. In the last was Sulayman with sixty thousand men to attack Tyana. Both Sulaymans withdrew from the territory of Byzantine Rome unharmed after achieving their targets. Malik and Battal got trapped. Emperor Leo and his son Constantine were waiting to trounce them. Both of them died fighting on the battle field. Out of their twenty thousand men only sixty-eight hundred could flee to safety in Synnada. From there they joined Sulayman’s withdrawing army to return to Syria.194, 195 The event did not compel Umayyad Caliphate to change its policy towards Byzantine Rome. It continued to send summer and winter expeditions. By that time Umayyad Caliphate was militarily engaged at all its borders. Such events were expected and were considered a by-product of raids. On the other hand, it was a marvellous achievement for Byzantine Rome. It had defeated an Arab force in open field after almost a century of military abuses at their hands. Same emperor Leo carried out the credit, who had successfully defenced Constantinople.

The Northern borders

Khazar Khanate and Umayyad Caliphate were two giants one-on-one. None was afraid of the other. Whole Caucasus region between Caspian and Black seas became their non-ending battle ground. Each year both armies came out of their camps devastated each other’s populations and cities and returned without gaining anything substantial. 196 Look at a passage of Khalifa: In 730 CE “al-Jarrāḥ [bin Abdullah al Ḥakami] marched from Bardha’a to Azerbaijan. He encamped with his army at Marj Sabalan. There was a river over which he built a bridge. To this day it is called al-Jarrah’s bridge (Jisr al Jarrāḥ). Al-Jarrāḥ marched against the son of Khaqān, who was besieging the inhabitants of Arbadil. They fought bitterly. Al-Jarrāḥ was killed – my Allah have mercy on him – on 22 Ramaḍān 112 [8 December 730], and the Khazars took control of Azerbaijan. Their cavalry roamed about unopposed, getting close to Mosul. They set up mangonels against Arbadil while the inhabitants of Ardabil were battling them. When the siege against them lasted too long, they surrendered the city, and the Khazars entered it. They killed the warriors and took the women and children captive. Al-Jarrāḥ was killed in Arshaq. When al-Jarrāḥ was killed, Hishām bin ‘Abd al-Malik sent Sa’īd bin Amr al-Ḥarashi with Arab knights riding post-horses. Sa’īd bin Amr went to Bardha’a. Al-Ḥarashi came to ….. to Baylaqan, and they went twards Adherbaijan. A khazar army was advancing. They had many carts on which they were carrying the Muslim prisoners and the booty taken from the inhabitants of Ardabil. Al-Harashi sent …. a scouting mission. [It] came upon the Khazar camp while they were sleeping, then …. [it] departed and informed him. He roused his men and marched against the Khazars, and rescued the carts and their contents. ….. He brought the carts into the city of Warthan, and wrote to Hishām about the victory…… Then he marched and confronted the tyrant (ṭāghiya) of the Khazars. Allah put them to rout, the tyrant fled and al-Ḥarashi rescued the Muslim prisoners and their booty. In Shawwāl 112 [December 760 – January 731], Maslamah bin ‘Abd al-Malik went out in pursuit of the Turks, in driving rain and snow, until he passed al-Bāb. He left aṭ- Ṭā’i to rebuild and fortify al-Bāb. He assigned a detachment for that . Then he sent the armies, and conquered cities and fortresses. The enemies of Allah burned themselves in their cities.197, 198, 199 The borders of Umayyad Caliphate and Khazar Khanate did not touch each other. There were buffer states between the two. These tiny princely states had to get ground between the fight of two genies.200

Armenia had been a trouble spot of Umayyad Caliphate in the past. It could create very little trouble for Umayyad Caliphate, if any, during Hisham’s tenure. The districts of Armenia and Azerbaijan were under administration of province of Jazira. The governors of Jazira continued to attend the Khazar threat without any fear of disruption from the hostile population of Armenia.

Revolts in Ifriqiya

The border policy in Ifriqya remained the same. Now and then the forces of the Umayyad Caliphate organized a raid targeting either the Mediterranean islands or the sub Saharan communities of Western Africa. The raids brought wealth and income for the participants. Some of it was definitely transferred to the central government.201 Things were as usual until later years of Hisham’s tenure. According to Tabari, a delegate of Berber Muslims, all of whom fell under the Mawla class, reached Damascus to see the caliph in person. This was too much of an expectation from them. They stayed in the capital for days but in the end realized that seeing the caliph was like spotting a unicorn in the wild. They handed a list of grievances to the master of ceremonies (ḥājib) and returned home. Among other they enumerated that the governors of the region used Berber Mawlas in raiding campaigns. They assigned the most dangerous positions in the war to the Berbers, keeping the Arab fellows at safer points. At the time of payment from the booty, the Arab governors paid little to the Mawlas as compared to their Arab counterparts. Moreover, the governors slaughtered thousands of Berber’s sheep yearly to find a purely white skinned lamb’s wool for the caliph without compensation. The practice was extremely taxing on Berbers because chance of getting such lamb was one in one thousand. Furthermore the governors took each and every beautiful daughter from the Berbers. The delegate had wanted to hear from the caliph that such practices were against the Qur’an and the Sunnah of the Prophet, which was the supreme law of the country. They had expected that the caliph would issue a statement that Islam doesn’t discriminate between Arab and non-Arab Muslims. They had hoped that the caliph would categorically deny his involvement in such a tyranny. 202 Tabari accuses the Iraqi Kharijis for blossoming of such ideas in Ifriqiya. He says they had gone all their way to Ifriqiya to propagate the concept of equality of every Muslim in the eyes of law. The only dilemma among the ever growing Khariji sect in the Berber Muslims was if they should blame the caliph or the governor for ongoing discrimination.203 In any case, the delegate returned empty handed. On their return, all the members of the delegate organized a coordinated uprising.204 In August of 740 CE the Berber soldiers took power in their hands everywhere in Ifriqiya from Tanjah to Kairouan. The uprising had spread to the forces of Umayyad Caliphate stationed in Spain, which were predominantly Berber. The Khariji Berber rebels either killed or expelled governors of Umayyad Caliphate. For the next two years Umayyad Caliphate sent army after army from Egypt to subjugate them. Ultimately, as it usually happens with the Kharijis, they split into groups. Syrian Troops sent from Damascus could control the situation in December of 742 CE.205 Interestingly, one of the leaders of rebels was al-Ḥaqīr, which means ‘the downtrodden’. He was a water-seller by trade.206

Final defeat in France

Despite defeat at Toledo, local governors of Umayyad Caliphate in Spain had not stopped dreaming of capturing France. In October of 732 CE, the forces of Umayyad Caliphate, under the command of lieutenant governor of Spain by name of Abdur Rahman al Ghafiqi, crossed the Pyrenees Mountains to descend into the fertile plains of Aquitaine Basin. Odo of Aquitaine fled after a brief encounter at the northern bank of River Dordogne. Forces of Umayyad Caliphate were in hot pursuit of Odo when, to their surprise, Charles Martel the Mayor of the palace of Austrasia marched all his way down to Tours. Both sides tried to harass each other out of the conflict zone for seven days. Finally they drew themselves up into battle lines. “The ‘Europeans’ stood immobile as a wall and held together like a glacier in region of cold and slaughtered the Arabs by sword in a blink of an eye.” Abdur Rahman al Ghafiqi got killed on the battle field. The survivors fled to Spain for safety, with their tails touching belly buttons, taking advantage of the darkness of night. Charles Martel did not believe in sincerity of Arab’s flight. His army kept patrolling the area for days under suspicion that the Arabs had hidden somewhere. 207, 208

Some modern historians dub the battle of Tours as the final recuperation of Western Civilization from the gash it received at the hands of Arabs at Yarmouk about a century ago.209

Rebellions in Sind

Conditions on the eastern border of Umayyad Caliphate were not entirely different from its western border during later years of Hisham. Tamīm bin Zayd was Junayd’s replacement in Sind. The district became volatile. Local population rose in resistance to the government. Arabs started quarrelling with each other. Daily killings became a routine. Tamim had to cede the control and run to Iraq. When his replacement, Hakam bin ‘Awāan arrived, he found that Sind had been overrun by the people of Kutch. He was compelled to build a stronghold (madīna) for the Muslims to take refuge in it. He named it Maḥfūẓah (protected). After fierce fighting, he drove out those who had overrun the land, and the country became calm and quiet.210211

The calm did not last long. The administrative structure of Umayyad Caliphate had changed in a way that when a superior retired or got dismissed, the juniors got automatically a termination letter. Not only this, they had to face jail and torture for no crime of theirs. When Hisham dismissed governor of Iraq Khalid bin Abdullah in 738 CE, Hakam bin ‘Awaan knew his fate. He slipped off across the border to die as a martyr at the hands of foreigners rather than to die of torture in a jail of Iraq. Mayth people of India took the credit of killing him.212, 213 The new lieutenant governor, ‘Amr bin Muhammad bin Qasim had to shift his capital. He built a town this side of the lake, which he named Manṣūrah and took up residence in governor’s palace. The locals proved tenacious. They crowned a king, and marched on Mansura to besiege it. ‘Amr asked reinforcements from Yusuf bin Umar, the new governor of Iraq. He dispatched four thousand men. Hearing the news, the king lifted the siege and retreated. Amr’s vanguard made a surprise attack on the king’s army by night. Great many of king’s army was killed. The person of the king was vulnerable but Arabs could not recognize him, even when passerby people used to call him “al Rāh!” (Rao). The king and his men took to their heels and Amr took firm control of the land. ‘Amr had just pacified the local rebellion when his own people started fighting. An army commander of Sind by name of Marwan bin Yazid bin Muhallab rebelled along with likeminded commanders and made off with Amr’s provisions and riding animals. Amr defeated him with help of the remainder of the army and scattered his men. Marwan fled. Amr proclaimed clemency to everybody except Marwan, who was turned in and executed.214, 215

Insurgency in Khorasan

Out of all newly engulfed areas during Walid’s government, Transoxiana proved to be particularly hard on Umayyad Caliphate’s stomach. Still, Umayyad Caliphate did not wish to regurgitate it. At the beginning of Hisham’s tenure whole of Khorasan, from Herat in the west to Fergana in the east and from Ghur in the south to Bukhara in the north slipped out of proper control of Umayyad Caliphate. The insurrection was the worst in Transoxiana. 216

As Hisham government started its long tenure, the yaman and Mudar brigades of the military came to blows. About thirty soldiers died in one such conflict fought in Balkh in Spring of 724 CE.217 Since then they never sat on one table in Khorasan.

Muslim missionaries were highly active in Khorasan. They were speedily converting local Turks to Islam. One of their teachings was that Islam grants equal rights to all Muslims whether they were Arab or non-Arab and whether their current generation converted to Islam or forefathers had converted. Tax collection dropped to a drastic level due to non-cooperation of these new converts. Local Turk tax collectors had already warned the government of missing the tax targets in case people continue to convert to Islam with that speed. The lieutenant governor Ashras bin Abdullah dismissed the conversion of many new Muslims as ungenuine and merely a tax evading strategy. He challenged them to either produce a certificate that they were circumcised, or demonstrate their ability to read a portion of the Qur’an to prove probity of their conversion.218 No nation changes its religion abruptly. Initially it accepts the core concepts of a new religion while maintaining many traditions of its previous religion and culture. Slowly, over many generations, it adopts further principles of the new religion. Sometimes it maintains few of its old religious traditions forever. The newly converted Turks were practicing hybrid Islam. Their viewpoint was that they had established mosques and prayed in them routinely. The government must accept it as ample proof of their change of religion. Muslim missionaries agreed with them in toto. Under public pressure, the district government got compelled to change its stance. This time they announced that the government doesn’t need to go into any detail if anybody has converted or not. All new converts would pay according to the formula by which they had been paying in the past. Conversion to Islam won’t change tax liability of anybody. About seven thousand embittered Turk mawlas, Iranian Dihqan Mawlas, and Muslim missionaries staged a sit-in outside the city of Samarkand in 728 CE. The police arrested prominent missionary members and dispersed the crowd forcibly. Disappointed from all venues, the Turk Mawlas and their converting missionaries joined hands with non-Muslim Turk lords.219 Their aim was to chase away forces of Umayyad Caliphate from their land and probably establish self-rule. (Gone were the days of early Futuhul Buldan when the new converts had to participate in jihad to prove their wholehearted acceptance of Islam. Now they had to show their circumcisions.). The number of people who took arms against the rule of Umayyad Caliphate under their leader, the Khaqan, whom Islamic sources give a nick name of Abu Muzāhim and who is known to be Suluk Khagan from other sources, is estimated to be hundred thousand. They resorted to guerilla type warfare. Forces of Umayyad Caliphate faced their surprise attacks and destruction which such attacks can bring, followed by their disappearance from the scene. Soldiers of Umayyad Caliphate were used to pitched battles and didn’t know what to do with the elusive enemy. Fear spread in rank and file of the government officials. Grip of the Umayyad Caliphate got limited to urban areas.220