Abdul Malik the statesman

Once upon a time there was a sage in Scotland by the name of Adam Smith. He said, “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own self-interest.” 1 His saying became proverbial. If we expand this concept to governance, it is not from the benevolence of governor that we expect good governance, but from his regard to his own self-interest.

Abdul Malik had an obligation to provide good governance to the war-torn country. His success in the task is beyond any doubt. Abdul Malik made far reaching constitutional and organizational changes. 2 All came gradually during the thirteen years he reigned after the end of the Second Arab Civil War.

Islam as state religion

The Second Arab Civil War had been hugely divisive and Abdul Malik realized that he needed to try to bring some unity to his fractious community and to demonstrate to his subjects and those beyond his reach that Umayyad Caliphate was still a force to be reckoned with.3 He had observed how much popular support his rival Ibn Zubayr had gained initially by setting himself up as a champion for the primacy of the Ka’ba and of the Prophet Muhammad.4 He had also observed how much support the Kharijis got in the name of Islam and how die hard the Shi’a Ali were just for the sake of religion. He decided to ratify Islam as a cementing material to bond together fragmented political groups of his vast country.

Practicing Islam had been immensely popular in Arab and some non-Arab populations of the Umayyad Caliphate. The ruler had always been a Muslim. However, there was a reluctance to promote Islam as state religion before the Second Arab Civil War. Hoyland ponders that it was out of deference to the large numbers of Christians among the subject population and among the ranks of the military.5 The Abdul Malik government elevated Islam to the level of state religion. Islam played a pivotal role in public life. Symbolic representation of Islam as a state religion was the formula, ‘no God except Allah and Muhammad Apostle of Allah (lā Ilāhah illallah o Muḥammad ur rasūl Allah) which, Abdul Malik government placed on all public docements and stamped on his new coinage. 6, 7, 8

Abdul Malik’s aniconic coin from 696 CE.9

Government sponsored written Islamic traditions

When humans get defeated they start writing history for future generations. During the latter half of Abdul Malik’s tenure there were many among Muslims who felt defeated. That was the time when historical traditions of the movement called ‘Islam’ got written for the first time.

When the Abdul Malik government observed so many opposition scholars publishing journals with their peculiar viewpoints, it was compelled to jump into the arena. The government hired scholars, provided them with the needed resources, and instructed them to pen down historical traditions under government oversight.

That was the same written material on which the future historian of Islam would bank. None of historical material written by Islamic scholars during Abdul Malik’s period has survived in original form. Some has survived in the form of quotation in later books.

State censorship

They say state censorship was born the day media was born. We have ample proof that the Abdul Malik government, like all previous governments, actively censored the written and verbal material in circulation.

Tabari informs us that people composed poems about the heroes of Tuwwabun but the poems remained underground. 12

It appears that government censorship was selective. Some historical facts already had religious explanations. Tabari preserves a dialogue between a Shi’a Ali supporter of Mukhtar and Abdur Rahman bin Muhammad bin Ash’ath, an Ahl al Jami’ah supporter of Ibn Zubayr. This supporter of Mukhtar was a prisoner of war under the custody of personnel under the command of Abdur Rahman bin Muhammad. Mukhtar’s supporter accused Abdur Rahman that his grandfather believed and then he became unbeliever. 13 This was a reference to the role of Ash’ath bin Qays in Ridda Wars and the explanation of the war was the same which later Islamic sources stuck to. Obviously, the explanation didn’t hurt anybody in Abdul Malik government. The government would not have used its precious sources to suppress it or modify it.

Ya’qubi claims that ‘both his [Abdul Malik’s] grandfathers were among those banished by the Messenger of Allah’.14 This statement was definitely derogatory to Abdul Malik government. If it survived until time of writing of Ya’qubi, it was only because Abdul Malik government did not have ample sources to curb or modify those traditions which were already widespread. The government considered holding each and every tongue and pen futile and expensive.

Finally, there were definitely certain traditions which the government was touchy about. It was determined to ban them at any cost. Like black holes, we can assume the existence of such traditions only by their absence. The events of last day of Prophet Muhammad, for example, have survived only through pen of Ibn Shahab al Zuhri. Ibn Shahab al Zuhri had accepted position of chief historian in Abdul Malik government. How on earth, only one salaried scholar knew all of them and so many other freelance scholars knew nothing?

Poetry was a more powerful media than non-fiction prose. Poetry was a kind of social media of the time and possessed invisible wings. No wonder censorship effected the poets most. We regularly hear of death threats to the poets who voiced opposition to the government. 15 State censor of poetry was not to work in single direction. All of the dignitaries of the government, including the caliph, had hired poets whose job was to praise the paying personality. 16

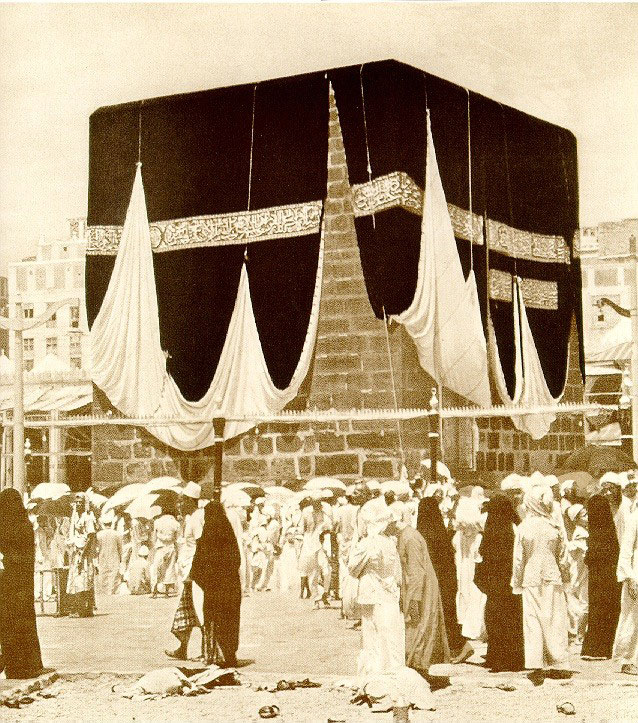

Reconstruction of the Ka’ba

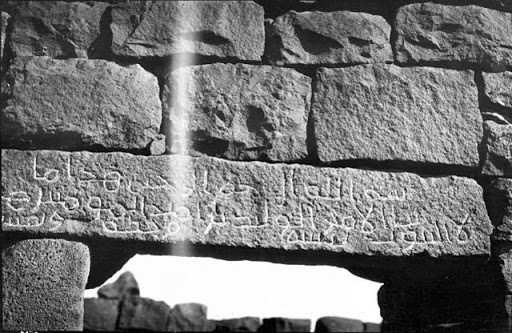

Al-Harithi has discovered an interesting inscription written on the face of a rock in the Ḥuma al-Numoor region of Saudi Arabia, northwest of modern town of Taif. The inscription reads, “Al-Rayyān bin ‘Abdullah testifies that there is no god but Allah and he testifies that Muhammad is the Messenger of Allah. Then reiterates to those to come to testify to that, Allah have mercy on al-Rayyān. May He forgive him and cause him to be guided to the path of Paradise and I ask Him for martyrdom in His path. Amen. This was written in the year the Masjid al- Ḥarām was built in the seventy eighth year”. 17

Inscription about the reconstruction of the Ka’ba.18.

Islamic sources give the reason of its reconstruction that the existing structure got severely damaged due to stoning by magnonels during the siege of Mecca by Hajjaj bin Yusuf.19

Ka’ba, final shape.20

Abdul Malik did not approve those changes in the design of the Ka’ba, which Ibn Zubayr had introduced. He ordered it to be reconstructed in exactly the same fashion as it used to be during the Prophetic times.24, 25

Sources are quiet as to why Abdul Malik reverted to the previous design. Either changes made by Ibn Zubayr were not popular among Muslims or Abdul Malik did not wish to give any credit to Ibn Zubayr as the final designer of the Ka’ba.

Anyhow, the Ka’ba and its harem acquired its final appearance. Their appearance was only altered in a few details before they were rebuilt in the 1950s. 26

Theophanes the Confessor blames that Abdul Malik wanted to take out the pillars from the holy Gethsemane (in Jerusalem) and use them in construction of the Ka’ba. Sergios, the son of Mansur could convince him to get them from Emperor Justinian. Abdul Malik and Sergios sent a combined request and Justinian agreed. 27

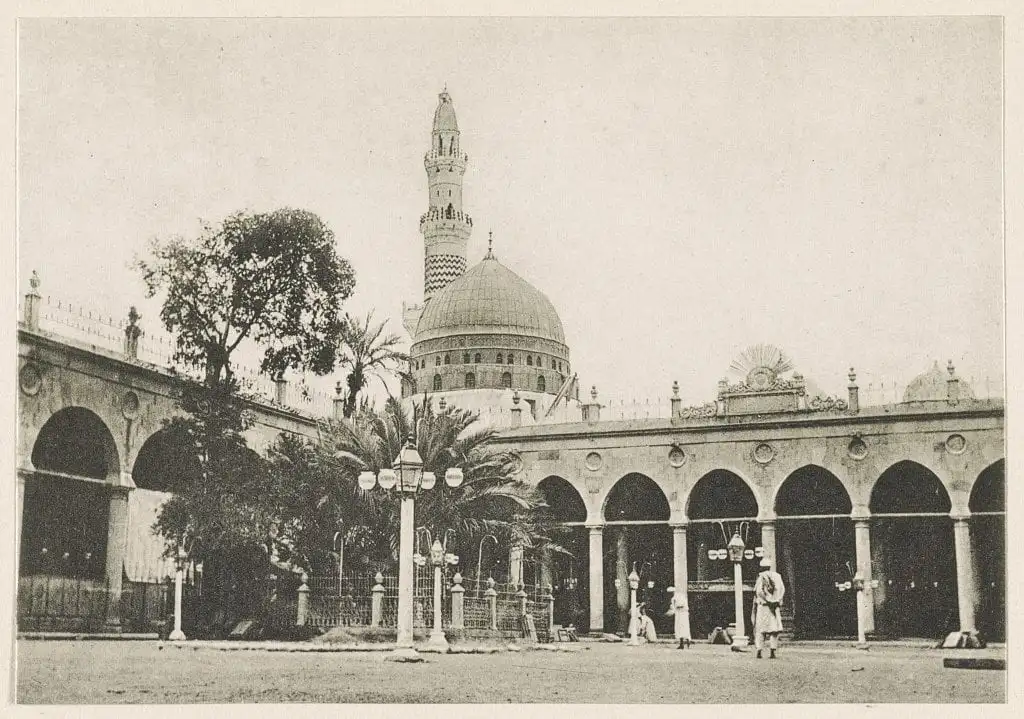

Sacralization of Jerusalem continues

From the very beginning the Abdul Malik government recognized the spiritual significance of Jeruslam for the Muslims and promoted it further.

Marwan bin Hakam had died in Damascus. Abdul Malik took the pain of travelling all the way to Jerusalem to take the oath of caliph.28 The precedent of taking the oath in Jerusalem was already present from Mu’awiya bin Abu Sufyan. Still, it was not a hard and fast rule. Marwan bin Hakam took the oath of caliph in Jabiya. Abdul Malik wished to demonstrate his reverence to the sacred site.

Abdul Malik did not leave the matter here. He ordered the construction of a dome on the rock, which had a reputation of being the site from where Prophet Muhammad started the ascent of his night journey (Mi’rāj). 29, 30 The Dome of the Rock was completed in 691 CE, just before Abdul Malik gained control of whole Umayyad Caliphate except Mecca.31

Dome of the Rock.32

Linguistic reforms

The Abdul Malik government gets credit for introducing a single official language of bureaucracy, namely Arabic. 38 Archaeological evidence suggests that Arabic was one of the official languages of Egypt just after Futuhul Buldan.39 The Abdul Malik government’s linguistic reforms applied to the rest of the country. Abdul Malik’s finance secretary, Sulayman bin Sa’d, who was a mawla and who had taken the office after Sarjun, was the one who started using Arabic for Syrian Diwan near the end of Abdul Malik’s tenure in 705 CE. 40 Sources suggest that Abdul Malik introduced Arabic as the sole official language in Iraq and the eastern parts of the country. 41.

Hawting comments that ‘though the tradition credits the introduction of Arabic as the official language to Abdul Malik and Hajjaj, the change might have been gradual starting in the beginning of eighth century. Arabic might have spread to border areas like Khorasan by the end of the Umayyad period’. 42 Hawting further notes that though it is difficult to distinguish Arabs from non-Arabs (mawlas) during the later Umayyad period, it appears that non-Arabs remained the main workforce in bureaucracy. The change of the official language to Arabic indirectly proves that there was a substantial know how of Arabic among non-Muslims.43

What happened to the Kharijis?

The Abdul Malik government had finished the Khariji entities in the Arabian Peninsula by force and had pushed the Kharijis out of Khuzestan towards Fars. However, the Khariji presence was far from over. One of the reasons of their persistence was the reluctance of Iraqi army to fight against them. The successive governors of Iraq, since Zubayrid take over, had been playing politics and probably keeping the issue alive deliberately to prop up their own political stature as compared to the central government. Abdul Malik faced the same problem that his predessosors had. When Abdul Malik noticed that his governor over Basrah, Khalid bin Abdullah, was not interested in giving Muhallab a free hand against the Kharijis, he dismissed Khalid. Abdul Malik gave the charge of Basrah to his brother Bishr bin Marwan who was already governing Kufa for him. 44 Now, Abdul Malik wrote a letter directly to Muhallab entrusting him full responsibility of war against the Kharijis. 45 Abdul Malik ordered Bishr bin Marwan at the same time to organize a big force from soldiers of Basrah and Kufa for Muhallab. 46 Bishr was sore that Abdul Malik had written directly to Muhallab, instead of allowing Bishr to pick a man. Bishr took it as a personal injury. He wanted to play politics around the issue. 47 He reluctantly provided soldiers to Muhallab and the army camped outside Basrah to prepare thoroughly for the campaign. 48 However, to good luck of Abdul Malik, Bishr died unexpectedly in May of 694 CE, before the army waged a war, before Bishr could play more politics, and before Abdul Malik and Bishr clashed openly.49 Abdul Malik quickly filled the vacancy of governor of Iraq by appointing Khalid bin Abdulla. 50 When the Iraqi soldiers heard the news of death of Bishr and his replacement by Khalid bin Abdullah, they no longer felt compelled to fight against the Kharijis. The common soldiers started absconding the camp in hordes and within days the army vanished. 51 Governor Khalid bin Abdullah tried to persuade the soldiers back to their camp but no plea or threat penetrated their thick skin. 52 Abdul Malik realized that Khalid bin Abdullah did not have skills to handle the rowdy soldiers. He started looking for another guy. Hajjaj bin Yusuf was an ambitious young man who had a resolve and guts to implement government policies. He had proved beyond doubt during his role in war against Ibn Zubayr and then as governor of Hejaz that he could go to any length to be in the good books of the caliph. In winter of 694 CE Abdul Malik announced dismissal of Khalid bin Abdullah and appointment of Hajjaj bin Yusuf as governor of Iraq in his stead.53, 54, 55

In his introductory speech, made in grand mosque of Kufa, Hajjaj told his audience that the central government had tried many governors in Iraq but ultimately it found the most appropriate one. He articulated all the harshness he was going to unleash upon the disobedient. 56, 57 To convince the people that he actually meant it, he practically put a few people to death who had deserted the army and were known malingerers.58 Herds of soldiers jammed the bridge across the river to take the road to Fars.59 After pushing the Kufan garrison out to Fars, Hajjaj reached Basrah and did the same thing there.60

Previously Muhallab was busy pushing the Kharijis eastwards with the help of around ten thousand soldiers.61 The arrival of locust of soldiers from Iraq to fight under Muhallab demoralized the Kharijis. On December 13, 694 CE Muhallab’s forces reached Ramhurmuz and expelled the Kharijis out of it without much fighting. The Kharijis retreated towards a region of Sabur called Kāzarūn. On December 25, 694 CE Muhallab’s forces camped at Kazarun opposite to them.62, 63 Muhallab was a smart general. Instead of keeping fighting against the Kharijis and hardening their resistance, he pursued a policy of active pressure from now onwards. For the next eighteen months Muhallab kept his army in combat ready state without a full scale attack. 64 The Kharijis were already a spent up force after their defeat at Ramhurmuz. The supply of new recruits had stopped reaching them due to strong government hold over Iraq and the Arabian Peninsula – their most fertile recruiting grounds. 65 By that time Umayyad Caliphate was collecting revenue from Fars, which was comparatively rich district and the Kharijis were collecting revenue from Kerman, which was comparatively poor district.66 Under military pressure, lack of new recruitment and financial hardships Kharijis split further in groups by spring of 696 CE and infighting started. About eighty percent of their fighters separated from Qatari bin Fuja’a under leadership of ‘Abd Rabb al Kabīr.67, 68 Hajjaj was getting impatient. He suspected that Muhallab was unnecessarily prolonging the war to keep draining the war funds.69 He sent an inspector to the battle field to check on Muhallab. The inspector reported back that Muhallab was actually fighting but with strategy. Muhallab explained to Hajjaj through his own envoy that he did not want to subject his men to unnecessary death when the Kharijis were getting weak day by day by killing each other. Hajjaj had to understand. 70 Gradually Muhallab’s forces pushed the Khariji presence back to Jirfut, the capital of Kerman. 71 The weakened Kharijis found themselves between the devil of the Umayyad Caliphate and the deep sea of the Baluch deserts. The Qatari group decided to flee to Isfahan and from there to Tabaristan. 72 Muhallab urgently attacked the remaining Kharijis killing almost all of them. Abdur Rab al Kabir died on the battlefield. The survivors were taken slaves because the Kharijis used to take non Khariji Muslims in captivity. 73 Hajjaj, then, sent a well-disciplined army consisting of Syrian Troops to help the Kufan soldiers of his lieutenant governor of Rayy to eradicate the Qatari group. The army did it within days. Qatari bin Fuja’a got killed on battle field. Most of his men died on the battlefield, few ended up being slaves. 74 By the summer of 696 CE Kharijis were totally eliminated and Syrian Troops had settled in Khorasan.75 This was the first instance after the Second Arab Civil War when Syrian Troops were used to maintain law and order in the country.76. Hajjaj also secured his seat by eliminating the Kharijis.

That was the final defeat of the Kharijis but not of Kharijism. Small and localized Khariji outbreaks did happen throughout Abdul Malik’s tenure. However, gradually the government gained the full capability to nip them in the bud before they got out of control. 77

Shi’a Ali go extinct

The second phase of the Second Arab Civil War had wiped out the Shi’a Ali as a political group for the time being. The tragedy of Karbala had deprived them of almost all potential leaders. Misadventure of Tuwwabun shattered their supporters. The impulsive decision of Mukhtar to revenge murderers of Husayn proved the last straw on the camel’s back. A handful of them survived the sacrilegious massacre conducted by Mus’ab bin Zubayr in Kufa after Mukhtar’s defeat. The surviving Shi’a Ali did not mind taking employment in the military and fighting on the orders of Abdul Malik. 78 The Shi’a commoners started co-operating with the government. 79

The Banu Hashim had divided into two camps by the beginning of Second Arab Civil War. The descendents of Abu Talib had supported the fight against Yazid and had sympathized with Husayn. The descendents of Abbas had parted ways from them and had taken allegiance to Yazid. Both groups diverged further after the Second Arab Civil War.

The surviving descendents of Abu Talib were confined to Medina. Abdul Malik government was particularly harsh to them. 80 Devoid of any political support in any corner of the country, they had only two options. One, they become the lackeys of Abdul Malik and survive in servitude. Two, they keep their grudge against the Umayyad government and become destitute. Most members of the Abu Talib group took the second option. 81. The poverty of Banu Hashim was well known. Zayd bin Ali rebelled in Kufa in 740 CE during caliph Hisham’s tenure. The ex-governor of Iraq Khalid bin Abdullah was in the wrong books of the caliph by that time. The serving governor of Iraq, Yusuf bin Umar, complained to the caliph that it was Khalid bin Abdullah who had provided money to the members of banu Hashim out of pity so that they would not die of hunger. And Khalid was the one who was waiting for success of Zayd’s rebellion. Hisham did not refute that Khalid might have provided banu Hashim money but refused to accept that Khalid was waiting for their success. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXVI, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Carole Hillenbrand (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 169.). The reason for the descendants of Abu Talib being relatively poor could be their spending habits. Mu’awiya bin Abu Sufyan is on record saying, “If an Umawi [Umayyad] were not taking care of his wealth prudently, he would not be like one of them. And if a Hāshimi were not generous and magnanimous, he would not be like one of them. However, you don’t hear about the eloquence, generosity and courage of Hāshimi.82

The case of the descendants of Abbas was different. Ali bin Abdullah was the youngest son of Abdullah bin Abbas. When Abdul Malik went for hajj in 695 CE, Ali met him and mentioned the difficulties Ibn Zubayr had imposed on his father because of his refusal to pay allegiance to him. Abdul Malik took him to Syria, settled him there, and remained benevolent to him. 83

Military reforms

One of the important changes in the government machinery, which came about in response to the political and social developments in Arab Muslim society, was the formation of something like a standing army at the service of the government, in place of the reliance on the mass of Arab tribesmen, which had been characteristic of previous governments in the Umayyad Caliphate. In the Abdul Malik period we hear, for the first time, of “Syrian Troops” being sent to the provinces to keep order and to participate in campaigns, while it is clear that in the provinces only some of the Arabs joined the army, others adopting a more civilian way of life. At the same time the governors appointed tended to be military men, having risen in the army, unlike those of the Sufyanids who depended on their tribal standing or relationship to the caliph. Symptomatic of the change is that we now no longer hear of the meetings between the Ashraf and the governor in the latter’s majlis or of the delegations (wufūd) of the local Ashraf to the caliph’s court in Syria, both characteristic of the time of Mu’awiya and Yazid governments. 84, 85

The process of creation of a professional standing army is not documented in detail by historical sources. One can assume that it was gradual but consistent.86 The Abdul Malik government had inherited a huge military residing in the cantonment towns and scaterred into the districs and border areas.87 The rank and file of army of the Umayyad Caliphate had broken down in the cantonments during the Second Arab Civil War. The military formations of border districts were still functional but their role was to raid the neighbouring countries and not to maintain law and order in the country. 88

By the beginning of Second Arab Civil war the only remuneration the soldiers got (‘aṭā’) was funded from the jiziya tax, which the government collected from non-Muslim subjects of the country. It was advance payment to fight. If a soldier could capture booty from the defeated enemy, it was extra bonus. 89

This formula of payment was awarded by the Umar bin Khattab government. By now, the generation that had participated in Futuhul Buldan was either in retirement age or dead. 90, 91 Their next generation used to receive ‘ata as their inherited right. This generation had not produced any source of jiziya tax by fighting. As the number of children in Arab elite was high, the per capita share of each soldier had thinned out. When Abdul Malik entered Kufa triumphantly, ata of soldiers of this garision town ranged from three hundred to seven hundred dirhams only. 92 For comparison, ata of an average soldier of Kufa garission was three thousand Dirhams by the end of Futuhul Buldan. 93

During the Second Arab Civil War no soldier was willing to provide military service inside the country only in lue of ‘ata’. Probably the prospect of booty was little encouragement in fighting with fellow Muslim Arabs. When the Zubayrid government sent military to fight against the Kharijis in Fars in 688 CE, the government had already paid the soldiers their annual ‘ata’ for that year. To convince them to fight, the govenernment provided them with a monthly ration (arzāq) over and above their ‘ata’ and in addition paid them a special grant (ma’āwin pleural, ma’ūwan single) on annual basis, equal in sum to their ‘ata’. 94, 95 Otherwise they would not have put their boots outside Kufa or Basrah. The low remuneration to fight was not the only problem. There was no system of retirement in the military. All the original soldiers of Futuhul Buldan had not died. They were too old to fight. Still the governments expected them to participate in the battles because they had received ‘ata’. 96

Abdul Malik was aware of the situation. He started organizing the army in a better way soon after gaining power in Syria. The first step was to withhold a portion of ‘ata’ of the next year if a soldier had not fought during the previous year. In 688 CE his Syrian soldiers did not participate in summer campaign against Byzantine Rome on excuse of muddy roads. He withheld twenty percent from their next year’s ‘ata’. 97 He could successfully establish a principle in his domain – no work, no pay. ‘Ata’ no longer remained a birth right of anybody in Syria because his ancestor had participated in Futuhul Buldan.

In the second step Abdul Malik applied the ‘no work, no pay’ formula to the cantonment towns of Kufa and Basrah. The Iraqi military was not enthusiastic in accepting the formula. Hajjaj, the viceroy over Iraq, announced that he would prosecute any man who avoided military service if he had received ‘ata’ that year.

Threats can compel a soldier to march to the battlefield but can’t motivate him to fight. The Umayyad Caliphate’s real nightmare about the fighting capacity of ‘ata’ recipients of Iraq came when a handful of Kharijis created havoc for fifteen months in whole of province.98 The government stood helpless in facing them.

The trouble started when Shabib bin Yazid (Shabīb bin Yazīd شَبيب بِن يَزِيد) and his hundred or so Khariji companions started an anti-government campaign on the night of May 21, 695 CE. 99 In this saga, well preserved in Tabari’s history, Hajjaj’s provincial government sent at least nineteen well equipped and well-staffed expeditions to tackle them. Each time they could kill the commander of the army and could disperse the soldiers. Some of these armies were as big as fifty thousand heads.100 The soldiers left the cantonment city under the pressure of the government. None of them fought on the battlefield. As soon as the action started they abandoned their commander and dispersed in all directions. The Kharijis could easily grab the commander and kill him. The commander didn’t have a choice other than facing the death with courage. If he escaped, Hajjaj would have prosecuted him for absconding and execute him. 101, 102

The registrants of ‘ata’ register not only earned notoriety for fleeing from the battlefield, they used all kind of excuses before leaving the town with army. Many of them applied for an exemption from military services on medical grounds. 103. Others offered another fighting person in their place.104 Still others resigned from military and returned their ‘ata’.105

Many residents of Kufa and Basrah, enrolled on ‘ata’ register, had some other source of income by that time. 106 They happily received government handouts in form of ‘ata’ to supplement their income. But as soon as the government called them to military duty they did their best to avoid it.

The Hajjaj government was obliged to strike the noncompliant ‘ata’ recipients off the military register. It saved the government millions of dirhams, which it used to recruit new soldiers from the general public on salary basis and pushed them into back-country military operations. 107 The newly recruited salary based soldiers consisted of about twenty percent of the Kufan and Basran regiments.108 Not only this, Hajjaj asked the central government to send ‘Syrian Troops’ to help the provincial government. 109 Hajjaj government paid them from local ‘ata’ funds. 110

When sources use the term ‘Syrian Troops’ after Abdul Malik became ruler over whole of the Umayyad Caliphate, they are actually referring to the national army recruited from general public, irrespective of their religious beliefs, ethnicity, tribal background or political affiliations. This national army was loyal to the government and to the caliph personally.

The newly recruited portions of Kufan and Basran divisions, in collaboration with the national troops – the Syrian Troops – could easily eliminate Shadid and his companions by early fall of 696 CE.111

The formula of advance payment to soldiers for their assignment as opposed to paying them a predetermined remuneration as an inheritory right must have been practiced widely in the Umayyad Caliphate. A letter written by a governor of Egypt to his subordinate tax collector somewhere in 710 CE and preserved in Egyptian National Library, Cairo sheds some light on it. The said governor demands from the subordinate to bring the jiziya tax revenue to the government treasury as soon as possible so the soldiers and their families could be paid and sent off to campaign. 112.

Military reforms continued to mold the army futher in shape. The government dropped the old system of the same basic salary to the whole regiment. It introduced a performace based salary scale. Soldiers were given a raise in salary by one notch after performing well in a battle. This raise was of a permanent nature and continued for the rest of their military career. 113 The disciplined and well performing soldiers and commanders were also rewarded by bonuses after an event. 114 The military personnel also received free treatment at the government’s expense in case of injury on the battlefield. 115 The government now routinely accepted the provision of a substitute as a legal way to drop out of military. 116 Finally, the newly recruited soldiers no longer got paid on annual basis. Their salary was on month-to-month basis.117

It appears that the brigades of the reformed divisions retained their original tribal based names.118

The development of a rank-based hierarchy in military, which had started during the latter phase of Futuhul Buldan, completed somewhere during caliphate of Abdul Malik. Sources demonstrate Hajjaj sitting on a chair comfortably in the battlefield against the Shabib Kharijis instead of fighting personally. 119 Similarly, Qutaybah bin Muslim sat comfortably on a throne during the war on Samarkand, while his army fought for him.120 Nobody objected to the non-fighter and supervisor role of the commander in both instances. This kind of role was unacceptable to the military during the early phase of Futuhul Buldan. 121

Finally, the military slogans started changing from purely religious to simply administrative. The battle cry of some Syrian Troops in the battle of Maskin was “O Hajjaj! O Hajjaj!” 122

Administrative reforms

Abdul Malik had observed how the Ashraf of Kufa and Basrah had been destabilizing governments from the time of Umar bin Khattab to Abdullah bin Zubayr. 123 He might have been suspicious of loyality of the Ashraf to his government, which had been so fragile in the case of Yazid and Ibn Zubayr.124 He was not in a mood to tolerate their nuisance. He did not award any significant post to any of the Ashraf after occupying Iraq, though he had promised to do so. 125.

Abdul Malik was clear that the country needed a monocratic central government to avoid any further civil wars. In the spring of 695 CE, after pacifying all the provinces and territories, Abdul Malik went for pilgrimage. There he made a speech at Arafat to the pilgrims who had come from all over the country. He made clear that he won’t tolerate opposition to his government. Even ctiticism to his government would be considered rebellion. Rebels would be treated in the same way, as he had treated Amr bin Sa’id.126, 127

The later years of Abdul Malik saw a gradual move away from the indirect system of ruling to a more centralized and direct form of the government. The middlemen, the Ashraf and the various non-Arab notables, who had stood between the government and the subjects, were replaced by officials more directly responsible to the caliph and his governors. 128.

The city and district level officials became responsible to the lieutenant governor. The lieutenant governors became answerable to the governor and the governor became answerable to the caliph. Nobody could bypass the chain of command. 129, 130 Each superior had the full right to hire and fire his subordinates. The incidences where a caliph directly appointed or dismissed a lower level officer were something of the past.

Each subordinate had to toe the government policy in toto. Anybody could pay the price of deviating from it with his life. 131

Some 9th century Islamic historians view the centralized administrative system as tyranny. Ya’qubi comments, “Abdul Malik had a penchant for shedding blood and acting in haste, and his governors were of similar character: al-Hajjaj in Iraq, al-Muhallab in Khorasan, Hisham bin Isma’il al Makhzumi in Medina, Abdullah bin Abdul Malik in Egypt, Musa bin Nusayr al-Lakhmi in Maghrib, Muhammad bin Yusuf al-Thaqafi (al-Hajjaj’s brother) in Yemen, and Muhammad bin Marwan in the Jazira and Mosul. All of them were tyrannical, unjust, violent, and headstrong. Al-Hajjaj was one of the most unjust of them and most given to shedding of blood.” 132

Since all appointments were merit based, the government machinery was run by equally competent individuals. In this scenario each senior had to remain vigilant that none of his junior becomes strong enough (socially, militarily or wealth wise) to replace him. 133.

Though the Barīd appears to be a postal system, the one in charge of the barid at provincial level was actually a spy of central government for local affairs. 134 This function of postal system is clear from a papyrus preserved in the Egyptian National Library in Cairo. This was written in January of 710 CE in the province of Egypt by a mid-ranking administrative officer to his subordinate. The officer concerned tells his subordinate clearly that the postmaster (ṣāhib al barīd) had informed him that the subordinate had fined some villagers for the non-payment of Jiziya tax. The subordinate should not bother any of the villagers after the receipt of this letter until the officer talks to the subordinate about the matter at hand further. 135

As the government adopted a more centralized approach to administration, the size of bureaucracy at the central government did not increase. The number of departments in the caliph’s office remained the same as they were during the Mu’aywia government. 136

Rebellion of the discontent

Thorough overhaul of the civil and military apparati of a country, achieved in a relatively short period in time, is not something of routine. It jostles many officials out from their hiding comfort zones and threatens privileges of many others who had taken them for granted. It also creates opportunities for the aspirants and introduces new ways to earn privileges. The Abdul Malik administration’s reforms engendered a big rebellion in the eastern part of the country. The rebellion was at such a large scale that at one point future of Abdul Malik government was at stake.137

The two groups were definitely adversely affected by the reforms. One were the overly ambitious Ashraf of Iraq and the others were the old styled soldiers in cantonments. The Ashraf were losing their status as middleman and hence their income. hey were also losing chances of getting higher government posts. The criterion of the higher government post had changed from links to caliph or a particular tribe to personal competency. The soldiers didn’t want to fight, particularly inside the country, but at the same time didn’t want to surrender their hereditary ‘ata’ rights.

Both discontent elements got a chance to vent out when Hajjaj sent them to fight in Sistan. Out of all ex-Sasanian districts, people of Sistan had been more tax evading since Second Arab Civil War. They had established their own semi-independent government under their king whose title was Zunbīl and who governed from Kabul. 138 Zunbil appears to be a capable leader who could perish many expeditions sent by Umayyad Caliphate to re-impose the taxes.139 Abdul Malik and Hajjaj were not comfortable with presence of a pocket of resistance in the geographical area, which they considered part of Umayyad Caliphate.140 Hajjaj prepared a formidable force of forty thousand consisting of both Kufan and Basran divisions and sent it under leadership of Abdur Rahman bin Ash’ath in 699 CE.141 142 The army, which contained a large number of Ashraf and ‘ata’ receiving hereditary soldiers, was particularly underpaid as compared to the standards of the time.143, 144 When the army reached fringes of Sistan, away from the oversight of the government, both Ashraf and common soldiers mutinied.145 They were not going to peril their lives against Zunbil, they declared. When government pushed them to march forward against the enemy, they decided to rather return to Iraq and pull their swords on the government managers.146, 147, 148 All of them headed straight to Basrah to meet their families.149 From whichever city or village the rebels passed, local garrison and Ashraf joined them. By the time the swollen number of rebels reached Basrah, left over Ashraf and soldiers of Kufa and Basrah joined them. No district of eastern part of the country remained unaffected.150 Many people of Khorasan joined the rebels, though lieutenant governor Yazid bin Muhallab remained pro-government.151 Hajjaj had to flee for his life.152, 153, 154 Initially, the rebel’s only demand was removal of Hajjaj from governorship due to his highhanded administrative methods. Soon, they declared their true intention – to get rid of Abdul Malik – the force behind the reforms.155 A horrified Abul Malik quickly offered removal of Hajjaj from the office and accommodation of the leader of rebels as a lieutenant governor in Iraq.156, 157 Hajjaj warned Abdul Malik of repeating the same mistake Uthman bin Affan had made. Hajjaj cautioned that removing a governor under pressure would simply embolden the rebels and they would then come to Abdul Malik’s throat.158 The matter resolved by itself as rebels, in their high spirit, rejected Abdul Malik’s offer.159 Abdur Rahman had not declared himself a caliph but he aspired to do so.160 Hajjaj, however, considered Abdul Malik’s offer to the rebels as his ‘no confidence motion’ in Hajjaj’s capabilities and tendered his resignation.161 Abdul Malik, naturally, did not accept it and sent his loyal forces from Jazira and Syria to bail Hajjaj out.162 Two pitched battles took place. First was at Dayār al Jimājim in which government forces defeated the rebels but let them escape in all directions to save their lives.163, 164 Probably the government’s strategy was to settle the matter amicably by granting amnesty to the survivors after gaining guarantee of future good conduct. The rebels, however, were not in a mood to compromise. They assembled again at Zāwiyah to try to dislodge the government.165, 166, 167 This time the government forces not only defeated the rebels but also hot pursued them to kill as many as they could.168, 169, 170 Hajjaj reasserted government authority over Iraq and the rest of eastern province. Abdul Malik did not want any rebel to survive to avoid such troubles in future. Whole eastern province plunged into post rebellion crack down. Hajjaj government traced all those rebels who had fled from the battle field and executed them after sham court cases. The purging continued throughout Abdul Malik’s tenure and even after it. It is estimated that a total of one hundred and thirty thousand rebels died either at the battle field, or later as a result of persecutions. Very few could save their necks by entering an affidavit that they had committed unbelief (Kufr) by disobeying a rightful caliph.171, 172 The rebellion was a sudden outburst of anger and frustration. It was not an organized political movement. This is the reason government could handle it successfully. The incidence once again proved Hajjaj’s superior capabilities as administrator and a war strategist.173

The rebellion was, no doubt, masterminded and executed by Ashraf and ‘ata’ receiving soldiers. However, some other discontent groups joined them. One of them were Qurra’.174 They were extremely unhappy with some of the government policies which they considered completely contrary to Islam.175 The Qurra were purely religiously motivated. Indirect evidence is that after the rebellion was over and the government carried out massacre of rebels all prisoners appealed for mercy and pardon except the Qurra.176 The other were non-Muslims. They included both Arabs and non-Arabs. The Christians of Najran, who had settled in Iraq on orders of Umar bin Khattab sided with the rebels, for example. Non-Arab land lords of Iraq also joined hands with the rebels. 177, 178, 179

The result of the rebellion of discontent showed that the monocracy created by Abdul Malik was to stay for now. Ashraf and the hereditary soldiers would no longer be a political force in the country.

A far reaching result of the rebellion was cessation of crown lands in Iraq. They were bone of contention since their very establishment by Umar bin Khattab government. When the rebels occupied the cantonment towns of Iraq, they burnt the military registers and the owners of neibouring lands seized pieces of crown lands that bordered their land.180 The government did not make any efforts to gain control of these lands again.

Wasit founded

The government had many reasons to build a brand new cantonment town in Iraq. Firstly, the ‘Syrian Troops’ had to stay in Iraq permanently for law enforcement after crushing of the rebellion of the discontent. The local Arab population of Kufa and Basrah harbored hostility against them.181 It was prudent for the government to establish a new location for their lodging. Second, for a long time the two provinces of Kufa and Basrah had been being governed by one governor. The governor had to move between Kufa and Basrah every six months to attend to the business of management properly. It was logical to build a new town at the provincial border of Kufa and Basrah from where the governor could look after both.182 Thirdly, the towns of Kufa and Basrah had persistently demonstrated bitter opposition to the sitting government. It was advisable for the smooth functioning of the government to avoid them.

In 702 CE Hajjaj built the new cantonment town near Kaskar as his new capital and named it Wāsit.183, 184. He decorated the town with a castle, a mosque and a Qubbat al Khaḍrā’.185 He shifted the ‘Syrian Troops’ to this city.186 This was the peaceful town where Hajjaj lived the rest of his life and where spear holding soldiers and their in charge walked in front of Hajjaj when he came out of his palace in the streets of the town.187

Fiscal reforms

As the rebellion of Ashraf and hereditary soldiers passed over, Abdul Malik government again got busy with reforms. Country’s fiscal matters were in a dire form of neglect since the beginning of First Arab Civil War. Mu’aywia government’s efforts were limited to ‘patch up’ type repair throughout its twenty years. Second Arab Civil War wrecked the left over fiscal system.

Soon after gaining control of the country, Abdul Malik sat with his governors to fix the damaged fiscal system. Like his civil administration, Abdul Malik organized his fiscal apparatus purely in centralized form.188

Archaeologists have excavated some written documents which shed light on government’s preoccupation with fiscal management during Abdul Malik’s tenure.

Nessana was a live town during Abdul Malik’s reign. Its ruins are present at the village of Nitzana in southern Israel. It has yielded papyri, about 200 in number, during excavations in 1930’s. One of them is P. Nessena 77 which is currently lodged in Rockefeller Museum, Palestine. This document contains two letters written in Hijazi style Arabic. The letters are written by a regional administrator to his subordinate tax collector. The letters are fragmentary and hard to read correctly. Both are related to one matter. The officer rebukes the subordinate that Allah does not like wrongdoing (zulm) and corruption (fisād) and that the subordinate was not hired to act sinfully (tathmūn) or behave unjustly (tazlamū). The officer orders the subordinate to correct the financial corruption he had done to the people of Nessena and threatens to take the money out of the subordinate’s property if he fails to correct it. The officer further reminds the subordinate that the people of Nessana are under ‘protection of Allah and the protection of His Messenger’ (Dhimmat Allah wa Dhimmat Rasūlihi). Hoyland dates this paper from late 680’s.189 This was written during Abdul Malik’s reign. This paper provides evidence that government officials used to collect tax from non-Muslim population directly and that the middle men were already absent in Syria. It further elaborates that the officials did their best to stick to the income tax law of the country and if any infarction of law did occur on the part of officials it was strictly dealt with.

Abdul Malik is credited with creation of a single uniform coinage in the country.190 “Gold and silver coins were first inscribed in Arabic in the days of Abdul Malik, Hajjaj being the one who did this”, alleges Yaqubi.191

Abdul Malik’s fiscal reforms might have an element of austerity because Ya’qubi taunts him to be a miser.192 It is on record that Abdul Malik reduced salaries of Iraqi troops, even before they fought against Kharijis under command of Muhallab.193 The decision had stirred riots among soldiers of Basran division. The government authorities had to curb them.194

The fiscal reforms had gone hand in hand with military reforms. By getting rid of compulsion of paying the military whatever the government collected in the form of jiziya tax, the government had more disposable funds at its discretion. It could budget funds to buy goods and services other than used by the military, for example, construction of iconic buildings. The caliph did not have to get any preapproval in deciding whose services to be bought and for how much. Apparently the caliph was the biggest buyer of goods and services in the country, he had oligosmy. All these factors created an impression among the sellers of goods and services that the caliph paid them out of his own pocket. It definitely enhanced the authority of the caliph in eyes of his subjects. Tabari reports an incident in which a group of ‘Anazah (a clan of Rabi’ah) tribesmen killed some rebels (probably Khariji) on their own initiative and presented their severed heads to Abdul Malik. Abdul Malik let them settle in Bāniqiyā, as a reward and assigned them stipends, something which they rarely had before.195

Abdul Malik reforms coin

While introducing unified currency in the whole country Abdul Malik government achieved another milestone. It designed the first coin in history of Islam which did not bear any human figure. Rather it had religious inscriptions written in Arabic. Both Ya’qubi and Tabari give credit of minting first aniconic coin with Arabic inscriptions to the Abdul Malik government. Tabari allots this event to 695 CE (76 AH).196 Archaeological finds confirm the reports of Islamic sources. Aniconic dinars from as early as 696 CE (77 AH) are preserved in museums and private collections and dirhams are available from 698 CE (79 AH) onwards.197.

Aniconic Dirham of Abdul Malik from 698 CE.198

Governor’s remunerations

It appears that Abdul Malik government brought revolutionary changes in remunerations of the governing managers at all levels. The government phased out salary gradually and introduced a franchise system. Each manager had to pay a reasonable amount to his superior annually (a kind of franchise fee). The chain started from the bottom level village tax collector and reached up to the caliph. Each level manager could pocket a certain amount out of the collected tax as his remuneration (a kind of profit). Each of the managers could spend his money as he wished, including to keep his subjects satisfied, and hence prolonging his tenure in the office.

Indirect evidence of the system is that we no longer hear troubles of audit imposed by the center on provincial governors or allegations of misappropriation of money on the part of higher office bearers from common people.

The system had an inbuilt recognition to the pivotal role a governor plays in management of a large province. It changed the perception of a governor in the eyes of common people. He was no longer a corrupt stealer, rather he was a smart entrepreneur.

The formula of change of remuneration of higher office bearers might have been introduced step by step. During initial years of Abdul Malik’s government payment formula of previous governments prevailed as far as remuneration of officers was concerned. After appointment of Hajjaj as governor over Iraq, when Hajjaj’s representative reached Basra to relieve Khalid bin Abdullah of his duties, Khalid vacated the governor house before the representative reached there. He then hastily distributed one million dirhams he had got in the provincial exchequer among the people. After that he resigned from his place of prayer (muṣallā’).199 Apparently he was afraid that the caliph would ask for audit and he didn’t want to pay back to the caliph. The situation changed slightly later. The central government raised Hajjaj’s salary. It was an obvious attempt to recognize the services of a competent governor, and to prevent a competent governor from being corrupt. During later years of Abdul Malik government the concept of salary disappeared. A great body of evidence suggests that the governor and district level managers were no longer salaried personnel during later years of Abdul Malik government. The franchise system of payments had replaced the salary system. When Muhallab returned to Basrah after defeating the Kharijis, Hajjaj demanded him to pay one million dirhams to the provincial government, he owed for governing the district of Khuzestan. Muhallab complied.200 Muhallab was not under threat of audit at that time. He was promoted from the post of lieutenant governor of Kerman – a war devastated district – to lieutenant governor of Khorasan – a wealth producing district. Muhallab did not deny the amount he owed but he did not have that much cash. He borrowed three hundred thousand dirhams from open market. His wife generated two hundred thousand dirhams by selling her jewelry. His son, Mughirah, who had been district manager of Ishtakhar under Muhallab, paid the rest of five hundred thousand.201 It was not a kind of fine which any outgoing governor had to pay during Mu’awiya government. It was a lump sum which a lieutenant governor had to pay to the provincial government, in lieu of his right to collect taxes from a district (a kind of franchise fee).

Governor of Khorasan, Umayyah bin Abdullah had announced nomination of Bukayr as in charge of Tukhāristan. Bukayr borrowed big money to buy horses and weapons. Meaning he had to spend something to earn from the district. He was expecting big income. Umayyah withdrew his orders unexpectedly. Bukayr could not pay back to his creditors, got bankrupt and ended up in jail.202

Ubaydullah bin Abi Bakrah was working under some kind of franchise system when he took expedition against Zunbil in 697 CE. He paid Zunbil seven hundred thousand dirhams to buy truce instead of fighting. His companions warned him that he should weigh his options between fighting and earning income or paying to Zunbil and loosing income.203 When Hajjaj dismissed Yazid bin Muhallab from the post of lieutenant governor of Khorasan, Yazid had to pay arrears of six million dirhams to the provincial government. Yazid did not dispute the amount because it was pre-determined and part of his job contract. He paid three million out of his pocket and borrowed three million to get a no dues certificate. Caliph Walid was sympathetic to Yazid but he did not write off his debt.204

The new system of remuneration recognized a superior’s right to pick his subordinates. No manager needed approval from his superior for this. When Muhallab got appointed over Fars, for example, he got a free hand to appoint his son Mughira bin Muhallab over Fasa and Darabjird and his other son Sa’id bin Muhallab over Arrajan and Sabur.205, 206

Due to franchise system of payments the central government no longer remained interested in getting share in petty border raids. Booty generated during big wars was, however, still dealt with according to old formula. In 704 CE Yazid bin Muhallab besieged Bādghīs. Its king, Nīzak made peace after paying him the treasure of Badghis. Tabari mentions that Yazid sent the news to Hajjaj but Tabari doesn’t mention any money sent to Hajjaj along with the news.207 Similarly, in 704 CE Mufaḍḍal bin Muhallab campaigned against Badghis. Mufaddal divided the plunder among the people. Every man received eight hundred dirhams. Then he campaigned against Akharūn and Shūmān. He again divided all the plunder among men.208 He didn’t send any share to the provincial or central government. He himself didn’t take anything out of booty.209

Companions lose ground

Abdul Malik government was particularly harsh on Companions of the Prophet. Hajjaj bin Yusuf, in his capacity as governor of Medina, hung lead seals around the necks of many Companions of the Prophet, including Jābir bin ‘Abdullah, Anas bin Mālik, Sahl bin Sa’d al Sā’idi and a number of others, to humiliate them.210, 211 People of Medina had not supported Abdul Malik government whole heartedly. Hajjaj’s attempt was to subdue the population of Medina generally.212 In doing so, he did not spare the Companions of the Prophet and treated them the same way he treated others.

This was the last political event in which any Companion of the Prophet got involved. All of them were above seventy five when Abdul Malik took power in Iraq.213 Many of them died one after another in succession during Abdul Malik’s time. Very few survived to see the next government change.

A regard for being Companion of the Prophet must still be present at grass root level. It could be this attraction that, by this time, certain men were present in the society who claimed to be a Companion of the Prophet but their claim could not be independently verified. A man of Taghlib named Qabisa got killed. Khalifa comments he was ‘said to have been a Companion of the Prophet’, meaning Khalifa could not verify the fact.214

Umayyads remained the richest

There was a lake in Armenia by name of Ṭirrikh. Rashidun Caliphate had left its water in public domain. When Muḥammad bin Marwān bin Ḥakam became governor of Jazira and Armenia, he converted it into his personal property. He marketed its fish for sale and pocketed its income. The property became hereditary and remained in Muhammad bin Marwan’s family.215 Such stories point out one fact. Though government owned properties contracted in number after distribution of much land in Iraq after unsuccessful rebellion of the discontent, they still existed. Their allotment continued during Abdul Malik’s period. This time caliph’s extended family was exclusive beneficiary.

Umayyads on construction spree

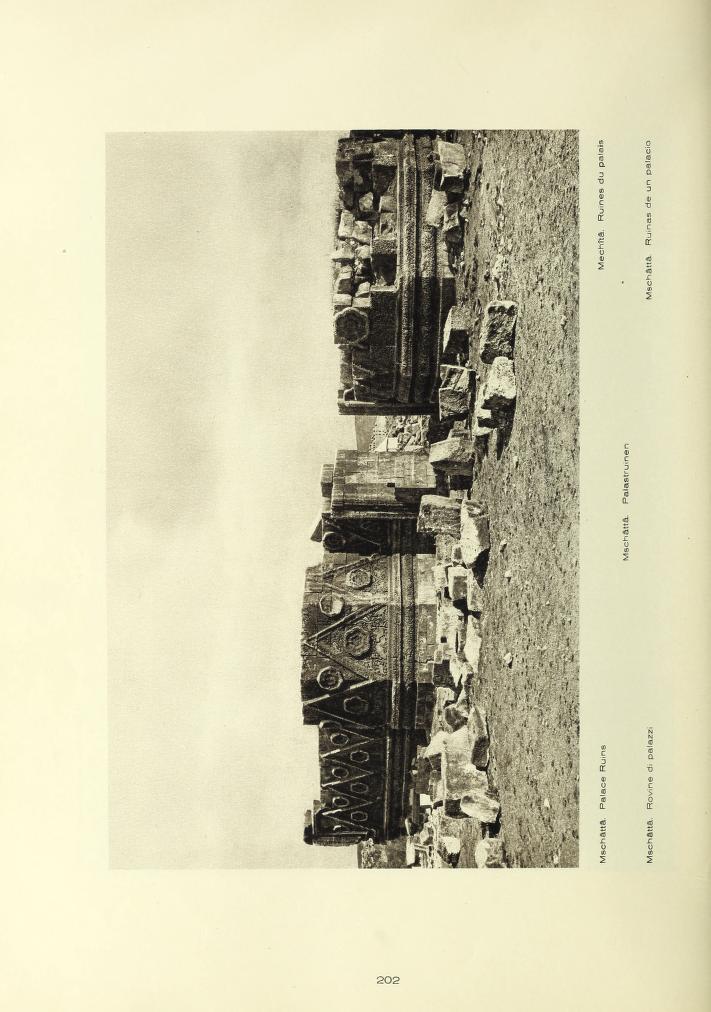

After success in Futuhul Buldan some Arab Muslims had got extremely rich. Trend to build luxury houses had started during Uthman bin Affan government. None of the residential houses built during Rashidun Caliphate, however, qualified to be called a palace. The trend to construct palaces was started by Mu’awiya himself. “Mu’awiya was the first in Islam to erect tall buildings and conscript people for their construction “, criticizes Ya’qubi.216 The first known building that earns the reputation of being a palace due to its elegance and splendor is al-Bayḍā’ owned by Ubaydullah bin Ziyad in Kufa. Ibn Ziyad had bought it from Abdullah bin Uthman al Thaqafi and renovated it spending one million Dirham which, Yazid bin Mu’awiya had gifted to Ibn Ziyad.217, 218, 219 the 1938 archaeological survey of the site is (Masjid al-Ku.fa 1940. See also Jana.bi. 1963; 1966; 2014). The second was in 1953 (Mus.t.afa. 1954). The third is in 1955 – 1956 (Mus.t.afa. 1956, 1963), The fourth is 1957 (Mus.t.afa. 1957, Taba 1971). The fifth is 1964 – 1965 (Jana.bi. 1963; 1966; Jana.bi. 1978). The sixth is 1966 and the seventh is 1967 (Jana.bi. 1983). The published plans are from Mustafa 1956. Khad.i.r 1983 figs 10 and 5 are redrawing of original plans. Photo credit of Qasr Imara: Michelina Di Cesare, 2019).

Dar ul Imarah.220

Qasr al-Mshatta.222

Walid’s inscription on Qasr Burqu.224

Khalifa of Allah formalized

An interesting coin from time of Abdul Malik has survived. This coin, minted in 75 AH [694 CE], records the title of the sitting ruler as ‘khalīfah Allah’.225 The finding has drawn a lively debate. Crone argues that actual title of ruler of Umayyad Caliphate was ‘khalifa Allah’ (deputy to Allah) and not Khalifa tur Rasul. She further insists that the title of ruler was Khalifa Allah from the time of Uthman, if not Umar.226

Out of all Islamic historical sources, it is only Tabari who records that the caliph was addressed as ‘Khalifa Allah’. And he keeps recording it over a time period. The evolution of the term can be traced clearly from his monograph. The term was first used for Mu’awiya and later on adopted by Abdul Malik. There is no evidence to suggest that Ibn Zubayr used this term for himself.

Arabs no longer a pure breed

Arab men had been taking non-Arab and non-Muslim women as their wives as well as concubines since first round of Futuhul Buldan. By the time Abdul Malik came to power, pure breed Arabs (children of an Arab man and an Arab woman) were already in minority. Overwhelming majority of those who called themselves Arab and used Arabic as their prima face were actually cross breed between Arab man and non-Arab woman. They had reached highest government offices without much hurdles as compared to their pure breed Arab counterparts. Bukayr bin Wishah, Abdul Malik’s first governor over Khorasan, was a son of an Isfahani mother.227 Mufaddal bin Muhallab, lieutenant governor of Khorasan was son of Bahlah, an Indian woman.228 Shabib bin Yazid, the Khariji who created havoc in Iraq, was a product of an Arab soldier who participated in Futuhul Buldan and a Roman mother captured in the campaign.229 Arab society still considered pure breed Arabs to be socially superior but as far as access to resources and opportunity to create wealth was concerned, they did not have more legal rights to their mixed breed counterparts. 230

Non-Muslims no longer needed in the government

As more and more skilled Muslims were available, Umayyad Caliphate no longer had to depend upon non-Muslims for bureaucratic jobs. Hajjaj’s finance secretary remained Zadhanfarrukh, who died in the office. After him Hajjaj appointed Yazid bin Abi Muslim.231. Yazid was a Mawla but Muslim. We don’t hear of any Christian on higher government post after death of Serjun bin Mansur. High ranking government officers of Christian faith didn’t lose their jobs, they died out.

Mawlas on next step in social hierarchy

The procedure of accepting Islam for a non-Muslim didn’t change throughout period of Umayyad Caliphate. He still had to be theoretically manumitted by a Muslim. That Muslim could be an Arab of mixed breed.232 As number of Muslims increased, the Muslim catalyst could be even himself be a Mawla.233 Once a person got the label of Mawla, it continued as sirname of the future generations of a new convert. A Mawla and his gernerations remained related to the original manumator, even after his death.234

Mawlas were still considered second class citizens by the Arab Muslims. As happens in such situations, the inferior group accepts the notion of them being inferior. When a Mawla got offer to lead the Qurrā’ Contingent in the rebellion of the discontent, he refused the proposal. The Mawla suggested that the commander of Qurra’ Should be a pure breed Arab Muslim. 235

Generally speaking Mawlas were not peasants. They were middle class people. Whenever Islamic sources describe trade of a Mawla, it is not tilling. A maula of Bukayr bin Wishah in Khorasan was an armorer. He used to make daggers.236 A Mawla by name of Ghāḍirah or Qayṣar used to be a contractor responsible for provision of supplies to the government troops of Hajjaj.237

Modern sociologists are discovering that a marginalized group of a given society works harder to achieve status as compared to the mainstream group. Despite odds, Mawlas progressed well in social hierarchy. Musa bin Nusayr is a typical example. He became full-fledged general of Umayyad Caliphate.238. Hawting observes that the Mawlas emerged as a political force and played significant role in future developments in Umayyad Caliphate.239

Mindset of non-Muslim subjects

Formation of a stable Arab government after end of Second Arab Civil War probably disappointed many non-Muslim subjects living in directly controlled provinces of Umayyad Caliphate. They lost any hope of establishing their own government. They kept paying taxes passively. Generally, attitude of Umayyad Caliphate towards them remained the same as was that of previous governments. However, after crushing of rebellion of the discontent, we hear anecdotes of highhandedness towards them. Hajjaj, for example, stripped the ancient doors of Zandaward, Dauqarah, Dārūsāṭ, Dair Māsirjasān and Sharabit to use them in the mosque of Wasit and its castle. The non-Muslim inhabitants of those towns protested that they had been granted the security of their cities and possessions, but Hajjaj did not mind what they said. 240, 241 Probably Arab Muslim elites were no longer afraid that the non-Muslim subjects could ever rebel successfully.

After Second Arab Civil War the main dilemma for the non-Muslims of directly controlled areas was which side of Arab Muslim elite to pick in case of their in-fighting. Kharijis of Shabib, for example, used to descend upon their villages and demand food and shelter without paying them. They used to provide but at the same time they were afraid that the Kharijis would depart the next day leaving them at the mercy of government forces, which would concuss them for co-operating with the Kharijis.242 When the non-Muslims compared the government of Umayyad Caliphate with the Kharijis, they found Kharijis more appealing. They perceived Kharijis merciful and accessible while the officially governing Muslims were oppressing and inaccessible in their eyes.243 This might explain partly success of Kharijis in challenging the government. However, non-Muslims were never sure that Kharijis would survive the government blitz. They never considered the Kharijis their savior. They always attached importance to obedience to the government. It was a Dahqan who tipped the government of Shabib’s plans of attacking Kufa in advance.244

The attitude of non-Muslims living in indirectly controlled districts and territories was different. They didn’t have to perplex between those Muslims who were officially governing and those who were opposing the government. Their dilemma was whether to pay taxes timely or nor. Most of the times their leaders stopped payments when they perceived it was doable. They had figured it out that it was not very risky. They knew maximum the government would do was to send a force demanding money. When it happens, they would simply apologize and pay arrears. Nobody would punish them or dismiss them to replace with another man. 245

Abdul Malik’s foreign policy

As Abdul Malik government got grip on internal situation of the country, policy of border expansion resumed.246 It appears that Muslim Arab political mind set was still fascinated by Futuhul Buldan.

Khorasan border

Due to non-ending hostilities between princes of central Asia, it had never been difficult for troops of Umayyad Caliphate to find allies among them. Some cenral Asian princes were readily available to co-operate with them, provided the target was their opponent prince. Before Second Arab Civil War had started, most of princes of central Asia were concerned if the situation continued, Umayyad Caliphate would gain permanent control over them. Khwārazm Shāh organized a round table conference of all the princes of the region in the fall of 681 CE. They agreed not to provoke each other, to settle their misunderstandings by negotiations, and not to invite the Muslims to their side in case of conflict.247, 248 However, advent of Second Arab Civil War dissipated the prince’s fears and they reverted to mutual fighting. The princes did not feel need to settle their differences after Second Arab Civil War finished because of the situation of Umayyad Caliphate on this front.

The Khorasan district of Umayyad Caliphate was particularly affected by tribal warfare during Second Arab Civil War. Restoring tribal harmony there was not an easy target for any incumbent government. Abdul Malik could successfully install Bukayr bin Wishah (Bukayr bin Wishāḥ بُكيَر بِن وِشاح), as his lieutenant governor over Khorasan by the end of Second Arab Civil War but could not neutralize its Arab population instantly. The tribal hostilities and attempts by opposing tribes to gain higher government posts at the cost of others continued by summer of 697 CE when Muhallab bin Abu Safrah took charge as lieutenant governor of Khorasan.249 Muhallab bin Sufrah rejuvenated the cross border attacks during his two years as lieutenant governor. The results were, anyhow, equivocal. Muhallab died of gangrene of his leg in August of 701 CE while returning from an expedition. He had to withdraw from that particular expedition prematurely due to tribal hostility among his own soldiers.250, 251 Muir rightly observes that too much tribal Jealousy in Khorasan explains inability of Muslims to subjugate the region properly, and their failure to extend the borders further east.252

Ifriqiyah border

Campaigns on Ifriqiya front proved most fruitful for Umayyad Caliphate during years of Abdul Malik. “Then came ‘Abd al Malik bin Mervān to power and everything went smoothly with him [in Egypt and Maghreb]”, reports Baladhuri253

The war started just after Abdul Malik came to power in the Western part of the country. One of the first acts of Abdul Malik government in the region was to rebuilt and strengthen the fortification of harbor of Tripoli.254 Gaining confidence from the strength of the fortifications Abdul Malik’s border forces tried on Tūnis/ Carthage (توُنِس). The Byzantine Romans were vigilant. They landed their army by ships, which repulsed the Umayyad Caliphate’s forces. A large number of Umayyad Caliphate soldiers, including the commander himself, got killed in action255

The defeat compelled Umayyad Caliphate to stretch itself in another direction. From 687 CE onwards field commander Hassan bin Nu’man came into conflict with local Berbers in the mountaneous region of Awras (اَؤراس). A queen, referred to as Kāhinah in Islamic sources, led the local Berbers. Her title indicates that she had some kind of spiritual authority over her subjects. After initial successes, in which the queen captured area up to Barqa, she got defeated. By 689 CE the queen’s domain was gone and many of her Berbers were in captivity in Fustat.256, 257, 258.

Defeat of Kahinah emboldened Umayyad Caliphate. Umayyad Caliphate appointed Musa bin Nusayr (Mūsā bin Nuṣayr مُوسىٌ بِن نُصَير) as Lieutenant Governor of border district of Maghrib in place of Hassan bin Nu’man in 697 CE.259, 260 He added whole of North Africa up to the Atlantic to the assets of Umayyad Caliphate. His army reached up to Ṭanjah, permanently occupied it, and settled Muslims there261, 262 Kairouan remained the administrative hub for whole region, while Musa bin Nusayr declared Tanjah a sub administrative center and appointed his Mawla Tariq bin Ziyad (Ṭāriq bin Ziāyd طارِق بِن زِياد) there as his proxy.263 Few details of the conquest have survived. During his first campaign in Ifriqiya, Musa fought against king Kusayla of Sanhaja Berbers in Ṭubna. The king fled and Musa could capture twenty thousand men in captivity. This was the principality which had killed Uqba bin Nafi. Musa’s forces had a feeling of revenge taken by their defeat.264.265 Apparently, the Berbers could not be subdued completely during this campaign because a raiding army of Umayyad Caliphate reached against Sanhaja again in 701 CE.266 By 703 CE Musa’s army had definitely reached the shores of Atlantic Ocean because Khalifa reports that in this year he raided Sekiouma in Ifriqiya. The same year he subdued Awraba Berbers.267268 The Berbers of the area accepted Islam faster because Baladhuri reports that Umayyad Caliphate used to collect sadaqah tax from here.269 By 705 CE Musa bin Nusayr had settled in Ifriqiya to the extent that he started sending naval expeditions to Europe. His navy added Syracuse of Sicily to the territory of Umayyad Caliphate.270.271, 272, 273, 274, 275 As we don’t hear of any expedition towards the deserts of north Africa, we can safely assume that Umayyad Caliphate had no interest whatsoever in them.

Byzantine border

Most bothersome border for Umayyad Caliphate was that of Byzantine Rome. This was the only border of Umayyad Caliphate where a country had power to halt territorial expansion. We don’t know how the truce between Abdul Malik government and the Byzantine Rome signed in 689 CE broke down. One thing is sure. Both powers had mistrust against each other. The truce was temporary cessation of hostilities from the perspective of both. Its breakage was natural.

As truce broke down summer and winter raids on Byzantine territory started like a ritual. They were exactly the same in character and strategy as their precursors. None of them resulted in any gain in territory. All were planned with a mind that the forces will return into border of Umayyad Caliphate after plundering.

We hear of campaigns from the year 694 CE onwards on a regular basis except in 699 CE due to plague in Syria.276 The last such campaign during the reign of Abdul Malik was in 705 CE, which returned before death of Abdul Malik.277 Islamic sources generally describe them as great successes. The only exception is the campaign of 704 CE in which defeat of Umayyad Caliphate’s forces is reported278

Byzantine Rome could not take any retaliatory action except on one occasion. During the plague in Syria, which almost annihilated everybody, and during which Umayyad Caliphate failed to carry out any raid in Byzantine territory, Byzantine forces attacked Antakya.279, 280 During the course of time Abdul Malik consolidated the defenses of border towns and sea shore towns.281

Cyprus was a special territory. The terms between Umayyad Caliphate and inhabitants of Cyprus had not changed since the times of Mu’awiya. Yazid had returned the garrisons but had not annulled the annual tributes.282 Similarly, the truce between Byzantine Rome and Umayyad Caliphate signed in 689 CE had revised the formula of distribution of taxes from Cyprus. It had not excluded Umayyad Caliphate from collecting tax from the island.283 emboldened by the success of raids in Byzantine territory, Abdul Malik added one thousand dinars to the tax on inhabitants of Cyprus.284 They had to comply.

Final subjugation of Armenia

Armenia had taken full advantage of Second Arab Civil War and had joined hands with Byzantine Rome. Justinian, the Byzantine Emperor had paid a state visit to Armenia to cement the union.285 First priority of Umayyad Caliphate in the northwestern border of the country was to yoke the Armenians. Abdul Malik assigned the task to Muhammad bin Marwan, his governor of Jazira and his brother. If Muhammad bin Marwan had to bring Armenia to subjugation of Umayyad Caliphate he had to fight against the Byzantine. In 692 CE the two sides marched out to meet each other at Sebastopolis, in the Pontus region of Anatolia. After a reasonable fight, Slav portion of Byzantine army defected and Muhammad bin Marwan won the day.286, 287 Tabari retains the relative strength of both armies. According to him Romans were sixty thousand while Arabs were only four thousands.288 Obviously, the Byzantine Rome side had still not gained political stability. Yet they had not expected such a humiliating defeat. They cut nose of their king Justinian and banished him to Crimea.289

Umayyad Caliphate was so furious against the moonlighting of the Armenians that Muhammad bin Marwan rounded up many Armenian nobles (Aḥrār) in a chuch located in the district of Khilāṭ and set the church on fire.290, 291

Despite defeat at the hands of Umayyad Caliphate and massacre of salient notables, the spirit of Armenians to create an independent state didn’t die. Muhammad bin Marwan had to march into Armenia again in 701 CE. After a brief confrontation the Armenians sought for peace. This time Muhammad bin Marwan decided to leave a lieutenant governor in Armenia to look after interests of Umayyad Caliphate. As soon as Muhammad bin Marwan’s army left Armenia, the inhabitants betrayed and killed his lieutenant governor.292 Next year, in 702 CE, army of Umayyad Caliphate penetrated again into Armenia up to Ṭurandah. This time the army stayed in the region, built their houses and settled in the country293, 294 The developments in Armenia were definitely unacceptable to Byzantine Rome. It attempted to retake Armenia in 704 CE. The Byzantine Army, which had come to rescue the Armenians, got routed. Muhammad bin Marwan ordered setting many churches and villages of Armenians to fire as a punishment to collaborating with the invaders. Some of the fires were in Nashawa and Sfrjān.295, 296 By 705 CE Umayyad Caliphate had full hold of Armenia. It could send unhindered expeditions in Armenia in summer as well as winter to snub the pockets of resistance. It could establish its resident leutinent governor over the territory. It could rebuilt the destroyed cities of Dabil, Nashawa and Bardha’a .297 Armenia returned to the same status of a vessel of Umayyad Caliphate, which it had been before start of Second Arab Civil War. 298

Trade wars

Baladhuri preserves an interesting case of trade wars between Umayyad Caliphate and Byzantine Rome. Futuhul Buldan didn’t severe trade relations between Byzantine Rome and its ex-provinces, now under new management. Egypt continued to export its papyrus (qarāṭīs) to Byzantine Rome and Byzantine Rome continued to export minted dinars to Umayyad Caliphate. Manufacturer of papyrus were Copts of Egypt. They used to inscribe word “Christ; at the top part of the papyrus and used to ascribe divinity to him “may God be highly exalted above that!” and used to put the sign of cross. As part of his policy of promotion of Islamic symbols in public life, Abdul Malik ordered to inscribe ‘in the name of Allah, the compassionate, the merciful’ on top of papyrus. Other Islamic phrases, like, ‘declare: Allah is one!” or ‘Allah” were allowed instead of ‘in the name of Allah, the compassionate, the merciful’ in this decree. The move provoked disgust and anger in Byzantine Rome. The Byzantine emperor sent a diplomatic protest to Abdul Malik that he was not diligent in his orders to inscribe such things on the papyrus which Romans hated. And if he doesn’t withdraw his orders Byzantine Rome would start sending them Dinars on which name of the Prophet will be associated with things which Muslims hate. As a result of the row Abdul Malik banned export of papyrus to Byzantine Rome and made arrangements of manufacturing of dinars inside Umayyad Caliphate. The export of papyrus could resume only after a while.299, 300

Death of Abdul Malik – linear succession formalized

“The fiction of an elective right vested in the whole body of the Faithful, though still observed more or less in form, ceased now to have reality, and the oath of allegiance was without hesitation enforced by the sword against recusants. The reigning Caliph thus proclaimed as his successor the fittest of his sons, the one born of the noblest mother, or otherwise most favoured, or (in default of issue) the best qualified amongst his kinsmen. To him, as heir-apparent, an anticipatory oath of fealty was taken, first at the seat of government and then throughout the empire, and the succession followed as a rule the choice. Sometimes a double nomination was made, anticipating at once thus two successions: but such attempt to forestall the distant future too often provoked, instead of preventing, civil war. The practice thus begun by the Umeiyads was followed equally by the ‘Abbāsids, and proved a precedent even for later times,” notes Muir.301 Transfer of power from Abdul Malik to his son Walid at the death of former is the first typical expression of statement of Muir mentioned above. Abdul Malik died on October 9, 705 CE in Damascus.302, 303 He had already assigned his son Walid as heir apparent.304 Only one soul in whole of the country challenged the decision. He was Sa’id bin Musayyab, a resident of Medina, who received flogs at the hand of the local governor for his audacity.305, 306 Abdul Malik government had eliminated any kind of opposition in the country. Gone were the days when Arab Muslims would flock towards meetings in each big city at the news of death of a caliph, present conflicting names for the post, and quarrel with each other in support of their favourite candidate. Selection of next caliph became internal affair of the ruling house.307 Common people accepted whatever the ruling house decided.

Abdul Malik’s place in history

From the very inception, Abdul Malik was resolute to install an autocratic government over the country. During the sermon of the only Hajj Abdul Malik performed in April of 695 CE, he is quoted to have said, “The caliphs who preceded me used to consume this wealth and let others consume it. I shall not cure the diseases of the Community except by means of the sword. I am not a weak caliph – meaning ‘Uthman – and I am not a devious caliph – meaning Mu’awiya. People! We will endure all the troubles for you, as long as there is no flag – raising or attacking the pulpit”308

The country Abdul Malik took over as a ruler was bitterly divided on geographic, religious, ethnic and political lines. Law and order in the country was at such ebb that even the life of caliph was not secure. We hear of conspiracies to kill Abdul Malik in March of 695 CE.309 Abdul Malik implemented his agenda inch by inch, cautiously but steadfastly. By the end of his tenure he successfully gathered all and sundry under one flag. That was the flag of the caliph. In Abdul Malik’s own words, which he uttered just before his death, “I do not know that anyone had a stronger hold on this rule than I. Ibn al-Zubayr prayed long and fasted much, but, because of his avarice, he was not fitted to be a leader.”310

In achieving so, Abdul Malik concentrated all powers in one hand – the hand of caliph. Political scientists call such rulers ‘Absolute monarch”. Abdul Malik was first absolute monarch in Islam.311. After him absolute monarchy became a norm in Islamic Middle East.

Here, a small clarification is needed. According to modern definition of the word ‘Absolute Monarchy’ is a system of government where power of authority is not restricted by any written law, legislature or customs’. 312 The definition is a bit misleading. Even the most powerful rulers in history had some kind of restriction to their power. They had to abide by the social and religious law of the country. We need a historical telescope and a historical microscope to find a single ruler who fulfills the above definition in toto. 313

In addition to holding the record of being first absolute monarch in Islam, Abdul Malik holds another record. If a general fights his way to power in a country, and successfully holds it, the political scientists call him ‘soldier king.’ Abdul Malik is the first soldier king in Islam. After him being soldier king became an acceptable norm in the Islamic Middle East.