Yazid assumes power

The transfer of power from Mu’awiya to Yazid (Yazid I) was as smooth as that between Abu Bakr and Umar. The military, the judiciary, the Ashrafs and the dignitaries, all supported him. At least a part of public opinion was in his favour as well. He did not change any governor or military commander. 1 2

He was the first caliph in Islam who had not seen Prophet Muhammad with his own eyes. 3 He was also the first caliph whose parents were not both Quraysh. 4 There might have been an annoyance among certain circles of the country regarding this fact. Mu’awiya is quoted to have said ‘a woman from Quraysh is better than a woman from Kalb’ about Yazid’s mother. 5, 6

Yazid did not organize an oath-taking ceremony, in which usually a caliph vowed to act according to the Quran and Sunnah of the Prophet. Perhaps he wanted to take the country in a different direction. 7 Archaeologists have discovered a coin of his, which he minted immediately after coming to power. This coin has no mention of Hijri year, which was official calendar of the country. Instead, it gives first year of Yazid’s ascension to power as a date of coinage, in imitation to the Sasanian kings. 8 The discovery hints that Yazid wanted to organize the country on a Sassanian pattern. Another clue that Yazid wished to take the country in a different direction comes from his special relations with his Christian subjects. Yazid further strengthened the bridge of friendship between the caliph and the Christian subjects of Syria. The Christians liked the previous caliphs but they loved Yazid. 9.

Inscription mentioning Yazid.10

Yazid faces political challenges

Yazid’s strongest weak-point was that he lacked his father’s social intelligence. Perhaps, he even didn’t know how to palpate the political pulse of Arab Muslims. He inherited a stable government and in a brief period of time, led it to instability. 11

Contrary to his father, Yazid could not tolerate the fact that a few renowned individuals in the country had not recognized him a caliph. Further, contrary to his father, he had the mindset to settle the matters by use of mere force rather than by gentle persuasion. The very first decision Yazid took after assuming power was to order Walid bin Utba (Walīd bin ‘Utbah وَلِىد بِن عُتبَه ), his governor over Medina, to arrest Abdullah bin Umar, Abdullah bin Zubayr (‘Abdallāh bin Zubayr عَبدُاللَه بِن زُبَير) and Husayn bin Ali (Ḥusayn bin ‘Ali حُسَين بِن عَلِي ) and to force them to give oath of allegiance to him. 12, 13 Abdullah bin Umar succumbed to the pressure. 14 Abdullah bin Zubayr and Husayn bin Ali were not in a mood to compromise under threats. They decided to test the popularity of Yazid. 15 Both Abdullah bin Zubayr and Husayn bin Ali were unarmed in Medina but they commanded respect among the residents due to their fathers. 16, 17 Governor Walid was reluctant to arrest them. He just suggested to them to take oath of allegiance to Yazid. 18 Without answering Walid’s request, both absconded from Medina to Mecca separately, each with a handful of supporters, in the darkness of the night in May 4, 680 CE. 19, 20 When Yazid received the news, he boiled in rage and dismissed the governor to replace him with ‘Amr bin Sa’īd, who had a reputation of being harsh with political opponents. 21 Yazid knew that the bird had flown the coop.

Debut of the Second Arab Civil War

Historians are unanimous on the date of end of the Second Arab Civil War. However, they disagree on its start date. Kaegi believes that the civil war started after the death of Mu’awiya. 22 Hawting thinks it started gradually during the caliphate of Yazid. 23 For all practical purposes it started on May 4, 680 CE when both Husayn bin Ali and Abdullah bin Zubayr left Medina in defiance to the government orders. 24

The posturing for the Second Arab Civil War took its final shape in the next few weeks after Husayn and Ibn Zubayr reached Mecca. The Second Arab Civil War was going to be as horrible as the first one. And again the winner of this gory war, that would be fought in the field of battle, in the domain of propaganda, and in the arena of religious proselytism, won’t be the one who was more pious or whose ancestors had been closer to the Prophet of Islam, but the one who was more pragmatic and closer to resources.

We don’t know exact reasons why Husayn and Ibn Zubayr chose Mecca. Probably, taking refuge in the sanctuary to avoid the pressure from governor Walid bin Utba was their initial intention. Once in Mecca, both of them picked up their future plans. Not only that they declared Yazid’s nomination to the office of Caliph unconstitutional, they presented themselves as suitable claimants for the job.

As Mu’awiya had not convinced his Arab Muslim subjects, rather he had imposed his son on them, many did not feel bound to that decision. Gradually, the Muslim Arab elite throughout the Umayyad Caliphate was divided into the same three parties which had fought the First Arab Civil War. Ahl al Jama’ah, whose leader was Yazid. Shi’a Ali, whose leader was Husayn. ‘Meccan Alliance’ whose leader was ibn Zubayr. ‘Neutral party’ emerged too. They again did not support any faction whole heartedly. They were willing to support anybody with whom the wind flies high. 25 The division of country on the same political stands suggests that twenty years of Mu’awiya’s reign had brought political stability, not political unification.

Yazid took the stand that he was the only hope of unity for Muslim Ummahs and his rivals were harbingers of division.26 Husayn took the stand that ruling over Muslim Ummah was the birthright of the Banu Hashim clan of Quraysh as they were the clan of the Prophet. 27 Abdullah bin Zubayr took a stand that the caliphate should belong to the descendants of one of those early immigrants from Mecca who participated in early wars along with the Prophet. 28 However, his dilemma was how to take Husayn out of the list of the sons of the early Muhajirun.

The Second Arab Civil War was about who should govern the country. It was not about how it should be governed. 29

Ibn Zubayr verses Husayn in Mecca

Apparently, Husayn did not have many supporters in Mecca. He kept a low profile there. The only people who gathered around him were those of his own family and clan who had accompanied him from Medina. 30 On the other hand, Abdullah bin Zubayr had supporters among the Quraysh of Mecca. He quickly dislodged the central government’s setup in the town and established himself in its place. 31 It appears there was no shurta force in Mecca to support the government representative, Harith bin Khalid. Ibn Zubayr did not declare himself ruler formally. His gesture of relieving Harith bin Khalid of his official duties was enough to an ring alarm in Damascus. It was only this gesture of Ibn Zubayr after which Yazid ordered governor ‘Amr bin Sa’id to send a force against Ibn Zubayr. 32, 33

Ibn Zubayr did not find any comfort in Husayn’s presence in the town. He perceived the latter as a political adversary. Both had a kind of cold war. 34 When Ibn Zubayr met Husayn in Mecca, according to Khalifa, he aptly asked Husayn what was keeping him from his Shi’a and the Shi’a of his father. If, Ibn Zubayr reiterated, he were in Husayn’s situation, he would have certainly gone to them.35 This was a gentle way to ask Husayn to leave Mecca and Husayn understood it. He knew Ibn Zubayr wanted a free hand in Mecca. 36 The cold war between the two must have contributed towards Husayn’s decision to leave for Kufa.37

First shot of the Second Arab Civil War

The new governor of Medina, Amr bin Sa’id, faced significant challenges in his role. Though he had the police force of Medina at his disposal, it was not strong enough to dislodge Ibn Zubayr from Mecca. Another issue was how to convince the policemen to attack and kill Ibn Zubayr in Mecca, who was declared a haram by the Prophet. The governor urgently raised forces from the Bedouin tribe of Aslam. Presumably, this force was underequipped but could supplement the Medinan police force in the attack and was willing to raid on the sacred site. The total number of soldiers was two thousand. 38, 39.

Ibn Zubayr organized his Quraysh supporters in Mecca in forces and supplemented them with members from the surrounding tribes. 40 This force easily defeated the forces of the provincial government that had marched on the vicinity of the city and chased them away. 41, 42, 43 Ibn Zubayr became the de fecto ruler of Mecca from where he was in a position to extend himself further. He didn’t proclaim himself as the caliph at this stage. He wanted to wait and see how the events unfold, particularly what decisions Husayn made. Husayn was in the town but didn’t participate in the fight. Defending the ‘Meccan Alliance’ was not on his agenda.

Husayn’s Maneuvers

Unlike Ibn Zubayr, fifty-five-year-old Husayn had no significant support in Mecca. 44 However, there was a strong presence of Shi’a Ali in Kufa and Yemen. 45 A group of Shi’a Ali was present in Basrah, though it was weak.46, 47

Husayn was weighing his options when a messenger of Shi’a Ali of Kufa met him in Mecca on June 14, 680 CE. He informed Husayn that Kufans were aching to be governed by him and invited Husayn to come and take over the city.48 Husayn did not take the offer of the messenger at face value and sent his young paternal cousin Muslim bin ‘Aqīl to Kufa on a fact finding mission. 49, 50, 51 In the meantime Husayn had consultations with his sympathizers in Mecca about his future strategy. Muhammad bin Hanifa was opposed to Husayn’s plans from the beginning. He had not accompanied Husayn from Medina. 52 Abdullah bin Abbas doubted the loyalty of Kufan Ashraf. He advised Husayn not to hurry towards Kufa until Kufans chased away Yazid’s governor on their own. The other option he tabled to Husayn was to go to Yemen, build guerrilla warfare and bit by bit dislodge the central government from the whole country. 53, 54, 55

Husayn took his own decision to bank upon Kufan support and his Meccan sympathizers parted their ways from him. 56 The only people who accompanied Husayn to Kufa on September 9 680 CE were those who had accompanied him from Medina. 57, 58, 59

Unrest in Kufa

On reaching Kufa, Muslim bin Aqil had found the conditions favourable. 60 While remaining underground, he claimed the allegiance of eighteen thousand men for Husayn in a few weeks. 61 They contributed towards a fund to buy arms for the final uprising. 62 Muslim bin Aqil gave a signal to Husayn to come to Kufa immediately and to lead the revolt in person. Yazid’s governor of the province, Nu’man bin Bashīr, turned a blind eye towards the development. 63, 64 All Kufans were not Shi’a Ali. Actually, the majority was ahl al Jam’ah. 65 They panicked and informed Yazid of the weakness of his governor. 66 When Yazid saw the province of Kufa slipping out of his hands, he dismissed governor Nu’man and replaced him with Ubaydullah bin Ziyad, his hawkish governor over Basrah. 67 In doing so Yazid once again combined two provinces of Kufa and Basrah. 68, 69.

On reaching Kufa, Ibn Ziyad found the city alien to the central government. The guards of the city and the common people in streets mistook him for Husayn and greeted him joyously as if Husayn had reached there from Mecca. 70 He lodged in the governor house without delaying a single moment and prepared a scheme to crack down on the opposition. He used the police force, the Ashraf of the town, and the loyal Ahl Jama’ah to re-establish the government’s writ. His spies quickly unveiled that Hani’ bin ‘Urwah of Murad tribe had hidden Muslim bin Aqil in his house. They arrested Hani to pressure him to produce his guest. Muslim bin Aqil was in a situation of now or never. He come out of his hiding and ordered Husayn’s sympathizers to assault the governor house without waiting for arrival of Husayn. 71 72 A big procession of four thousand leapt at the governor house where Ibn Ziyad was holed with a handful of supporters, most of them police officers and Ashraf. Ibn Ziyad sent the Ashraf to speak to the crowd and to threaten them by calling the Syrian Troops if they didn’t disperse. The Ashraf also communicated clearly that no participant of the procession would ever receive stipends. The trick worked and crowd started thinning out, ultimately leaving Muslim bin Aqil alone.73, 74, 75, 76

Political scientists tell us that there are three levels of political support. The weakest level is that of sympathy and vote. The next level is that of support with time and money. The strongest level is taking up arms and risking life. Muslim bin Aqil had overestimated Husayn’s support in Kufa. It was at the weakest political level.77, 78 Ibn Ziyad arrested Muslim bin Aqil and ordered him and Hani to be executed. 79 Ibn Ziayd did not bother to try them in a court of law, not even a sham one. This was a first instance in Islam where the government eliminated its political opponent by simply murdering them. Later, it set a precedent. 80

Tragedy of Karbala

Husayn had left for Kufa along with his family members including the women and children on the day of Muslim bin Aqil’s uprising, unaware of the situation in Kufa. He received the news of Muslim bin Aqil’s execution in the vicinity of Kufa. 81, 82 Husayn wished to return but he had to change his mind when the brothers of Muslim bin Aqil disagreed on the ground that they should at least try avenging his death.83 Probably, Husayn still had a glimmer of hope that the Kufans would support him militarily if they find him among them.84

Ibn Ziyad had settled the potential uprising in Kufa within two weeks. 85 Now, he put armed guards on all of the roads leading to Kufa to halt Husayn from entering the city. 86 The guards stopped Husayn at Mecca-Kufa road just few kilometers outside the town of Kufa. Husayn didn’t confront them, rather he deviated towards Kufa-Damascus road with an aim to see Yazid in person.87, 88 Ibn Ziyad had not anticipated it. He ordered his guards to halt Husayn again and sent a force of four thousand men under command of ‘Umar bin Sa’d bin Abu Waqqāṣ to confront Husayn.89, 90

Husayn was a big religious figure among Muslims. He was the closest surviving descendent of Prophet Muhammad. 91, 92, 93 Ibn Ziyad had difficulty in finding a man to command this army. Umar bin Sa’d bin Waqqas agreed to command this army after a promise that he would be granted lieutenant governorship of Rayy. 94, 95, 96, 97

During customary negotiations with Umar bin Sa’d bin Waqqas, Husayn proposed to Umar to either allow him to go to Yazid for negotiations, allow him to return to Mecca or to allow him to go to any border town to live an anonymous life. 98 The conditions sounded reasonable to Umar and his army.99 They held the view that Husayn had not committed any offence against the government. He had not revolted personally. He was on his way to Kufa on invitation from its citizens and now no longer wished to continue. 100 Why should he not be allowed to leave the venue? The conditions were, anyhow, not acceptable to Ibn Ziyad.101 He asked for Husayn’s unconditional submission to his person. 102 Husayn was a proud man.103 He made clear that such humiliation was unacceptable to him. 104

Ibn Ziyad ordered his army to kill Husayn if he didn’t submit to Ibn Ziyad. 105, 106 Such was the reluctance of the army to carry out the orders that one commander by name of Ḥurr bin Yazīd switched sides to Husayn and was killed defending him. 107, 108.

Umar threw a lance himself to encourage his soldiers to start the battle. 109 The day was the b10th of October, 680 CE and it was Ashura.110 It took about half a day for four thousand soldiers to kill the thirty horsemen and forty two foot soldiers of Husayn. Husayn was the last to die on the battlefield. It was the five men battalion under the command of Shamir bin Dhi al Jawshan of Hawazin who killed him. They severed his head from his body and Shimar took it to Ibn Ziyad as a trophy. Ibn Ziyad sent it to Yazid. 111, 112, 113, 114, 115. This was one of the earliest examples of mutilation of a dead body in Islam, which was otherwise considered a war crime. 116, 117, 118, 119.

The death toll of the forces of the provincial government was eighty eight. The wounded were extra. Umar bin Sa’d prayed over them and buried them. 120 The death toll on Husayn’s side was seventy two. Sources don’t mention anybody praying over them. The next day, residents of the nearby Ghādiriyyah village, who belonged to Asad, came to the venue and buried the bodies of Husayn and his companions. 121, 122, 123 The Tragedy of Karbala attracts detailed attention from all Islamic sources. However, non-Islamic sources are totally mute about it. It appears that the incident was too insignificant to catch the attention of contemporary Christian writers but it had such far reaching political implications that Islamic sources writing during the Abbasid Caliphate had to deal it like a milestone in the history of Islam.

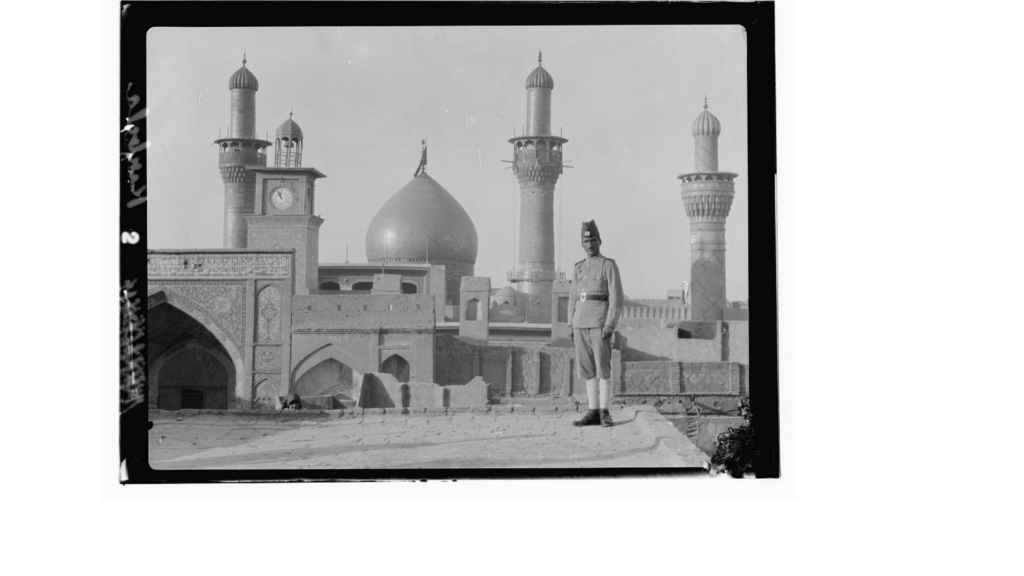

Tomb of Husayn bin Ali124

Phenomenon of martyrdom

Those who die knowingly for the sake of a great cause remain alive in the memories of people. It is not the death itself which makes a person a martyr, it is the undauntedness with which a person faced the death. Husayn immediately attained martyr status in the eyes of all Muslims, both Shi’a Ali and Ahl al Jama’ah. Here is a piece of poetry composed by ‘Ubaydullah bin Ḥurr, the son of the slain warrior Hurr bin Yazid, a few years after Husayn’s death:

A treacherous governor, the very reality of a treacherous man, says:

Should you not have fought against the martyr son of Fāṭima?

O how much I regret that I did not help him!

Indeed, every soul that does not set upon the right course regrets.125

By the time Tabari was writing his history, the mode of the death of Husayn was straightforward murder (maqtal) in the eyes of his contemporaries.126, 127, 128, 129

“Karbala was such a big tragedy for Ali’s and Fatima’s descendants,” points out Hawting, “that when Yazid died after a while, they were unable to take advantage of the situation. And that is the reason Mukhtar Thaqafi had to take another line of Ali’s descendants.”130.

Who decided to murder Husayn?

Yazid was pleased when hearing the news of death of Husayn. 131 However, he soon realized that he had committed a political blunder. 132 There was not a single political dignitary in the country who praised this action of Yazid. Even members of his inner circle, like Yaḥyā bin Ḥakam, publicly criticized him on this matter. 133, 134 He quickly distanced himself from the murder. Yazid told the messenger who had brought the heads of Husayn and his companions that the killing of Husayn was not a required thing for Ibn Sumayyah to prove his loyalty. He wept on this incident in front of everybody present and publicly blamed Ibn Ziyad for the mishap. 135 A few days later, when Ibn Ziyad asked Yazid what to do with the imprisoned women and children of Husayn, he ordered him to send them over to him. 136 Yazid dealt with them kindly and generously. 137 That time he declared in front of everybody present that if he were to decide the fate of Husayn, he would have decided differently from Ibn Ziyad. He then sent the women and children to Medina respectfully. One special person among them was ‘Ali al-Aṣghar bin Husayn bin Ali.138, 139, 140, 141

Ibn Ziyad was not very happy for being made a scapegoat. 142 He tried to pass the buck on Umar bin Sa’d but the latter flatly refused to accept responsibility for the murder. He stood firm that Ibn Ziyad had ordered him to do so in writing. 143 Ibn Ziyad himself did not have any written instructions from Yazid to prove his innocence. According to Tabari, when Yazid received the news of the execution of Muslim bin Aqil and suppression of unrest in Kufa, he simply ordered Ubaydullah to arrest anybody on the suspicion but kill only those who fight. He also ordered him to set lookouts and a watch against Husayn and to keep an eye on suspicious characters passing on the roads. 144

Yazid’s fending off measures didn’t earn him any dividends. He was overall responsible for the heinous crime in the public eye.

Abdullah bin Zubayr harvests what Husayn sowed

The only person in the country who reaped the reward from the situation arising from death of Husayn and curbing of Shi’a Ali’s revolt was Abdullah bin Zubayr.145 His ‘Mecca Alliance’ emerged as a single possible political alternative in case the people got fed up with the governance of sitting caliph. Hejaz had never been a staunch supporter of Ahl al Jama’ah. 146 They were governing over Hejaz by force. In the absence of any political rival, the people of Hejaz were apt to accept leadership of Abdullah bin Zubayr. 147 He took advantage of the situation without wasting any time and declared himself as the ruler of Hejaz, independent of the central government in the beginning of 681 CE. The people of Hejaz took oath of allegiance with him. 148, 149, 150 Ibn Zubayr preferred to be called by title “One who seeks refuge”. 151

Battle of Harrah

Medina had supported Ali during the First Arab Civil War. The people of Medina were ambivalent at the start of the Second Arab Civil War. After Husayn’s death, all the people of the town, including Ansar and Quraysh, leaned towards Abdullah bin Zubayr. 152 Yazid tried to maintain his grip on the town by changing governors. 153 He was receiving reports that the majority of Hejaz stood behind the leadership of Ibn Zubayr. 154 Yazid expected Walid bin Utbah, who had replaced Amr, to crush the opponents with an iron fist as Ibn Ziyad had done in Kufa few months ago. Walid, anyhow, did not have a dedicated group of ahl al Jam’ah in the town as Ziyad had in Kufa. He found himself weak and found Ibn Zubayr strong and cautious. 155 Just to increase the hurdles of Walid, by this time the people of Yamama accepted Khariji doctrine en masse and came into open revolt against the Yazid government under their leader Najdah bin ‘Āmir of Hanifa. Their inclination was towards political alliance with Ibn Zubayr. 156 Under distress, Yazid replaced Walid bin Utbah with ‘Uthmān bin Muḥammad bin Abu Sufyān on the suggestion of Ibn Zubayr, in a hope that the change might produce a soft corner in heart of Ibn Zubayr for Yazid government.157, 158 The young and inexperienced Uthman couldn’t handle the situation. 159 Disappointed from all venues, Yazid organized a meeting with the dignitaries of Medina at Damascus with the mediation of governor Uthman. Yazid bestowed upon them the gift of hundreds of thousands of Dirhams. 160, Bribing didn’t work. All of them kept the gifts but didn’t change their mind. They returned to Medina publicly vilifying Yazid’s character. 161 Nothing worked out and ultimately people of Medina raised banner of revolt under their leader ‘Abdallāh bin Ḥanzalah al-Ghasīl of Ansar. 162, 163 They herded the handful government officials and government supporters to one place and let them leave the town with the promise that none of them would inform the forthcoming forces of central government about strategic deployments in Medina. 164, 165

The events in Hejaz alarmed Yazid. Hejaz was not a significant province as far as revenue generation or military strategy was concerned. It must be the immense popularity of Abdullah bin Zubayr that abashed him. He apprehended the spread of his cult to other parts of the country. He decided to unleash the Syrian Troops, which had been being portrayed as a dreaded force, to impose central authority over provinces for the last quarter century but had never been used. The people of Hejaz, on their end, had resolved not to take the threat of use of the Syrian Troops on face value. They wished to test the waters.166

Within days, Yazid raised an army of twelve thousand men, all well paid.167 The army descended on Medina on August 27, 683 CE. 168 The citizens of the town came out for an open battle at the Harrah located to the east of the town. Hence the name ‘Battle of Ḥarrah’.169 Medinans were defeated within the hour. 170, 171, 172 The army of the central government treated the defeated citizens of Medina as combatant enemy. They not only killed some prisoners of war, whole city was given to the license and rapine of the army for full three days.173 This was the first example in a Muslim state of killing and plundering a Muslim town. After that it set a precedent. The survivors either pledged allegiance to Yazid or escaped to Mecca to join hands with Abdullah bin Zubayr. 174. Ali bin Husayn had taken residence at Yanbu near Medina. When the people of Medina came in open disobedience to the central government, he assured Yazid that he was not involved in the matter. Obviously, the Shi’a Ali were too weak at this stage to take any risk. Yazid had ordered the invading army to protect Ali bin Husayn and the army did. 175, 176.

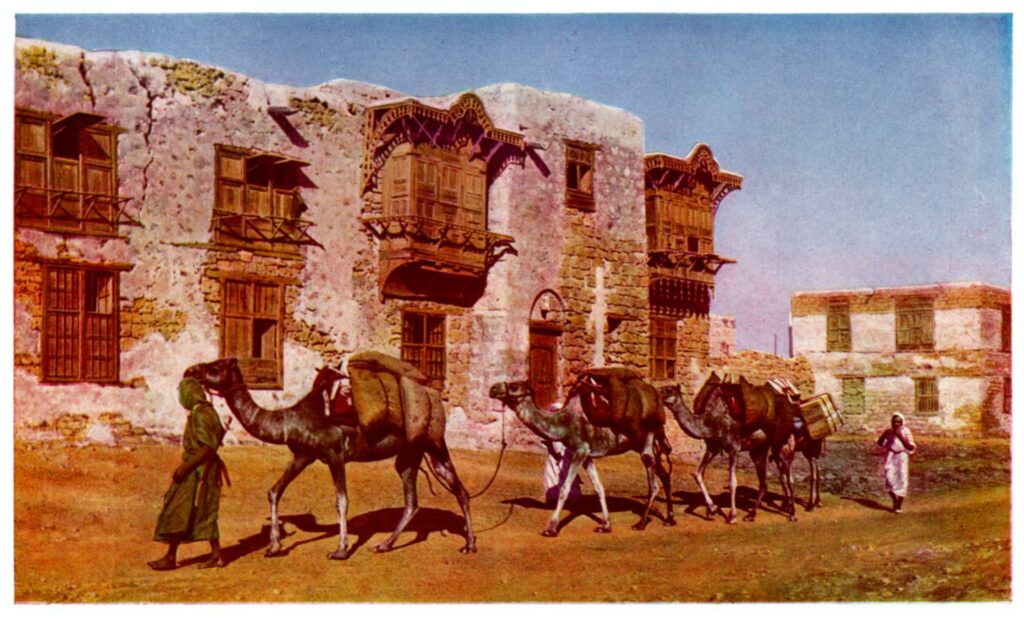

Old photograph of Yanbu. The Hijazi towns might not have changed much in look.177

The Battle of Harrah is the last episode in the history of Islam in which the Ansar of Medina participated as a group. 178 The battle was a fatal blow to them. They lost political significance for ever. The group’s name ‘Ansar’ scaled down to merely a surname among the future generations of Muslims.

Medina itself underwent further political downgrading. After the Battle of Harrah the only political significate Medina retained was that it became a refuge for the important families excluded from power. From here onwards, Medina distinguished itself as a scholarly city playing the role of a crucible for the study of the holy text and the first Muslim historiographical tradition.179

First Siege of Mecca

After imposing ‘peace’ on Medina, the army of the central government marched into Mecca. 180, 181 Abdullah bin Zubayr was not an easy target. He had gathered his supporters from all over Hejaz including Medina. The Kharijis of Yamama had also snuck in to help him under their leader Najada bin ‘Āmir because they considered protecting the Ka’ba from the invaders a religious duty. 182, 183 The army had to besiege the city. This city had no walls. The term ‘besiege’ means they blockaded the city. 184 Yazid’s management outside Hejaz had already blockaded the city and they were routinely checking traffic and returning those to their origin who intended to support the efforts of Abdullah bin Zubayr.185, 186, 187. When the siege was prolonged for a month, the army of the central government started bombarding the city, including Ka’ba, with stones with the help of ballistics. 188.

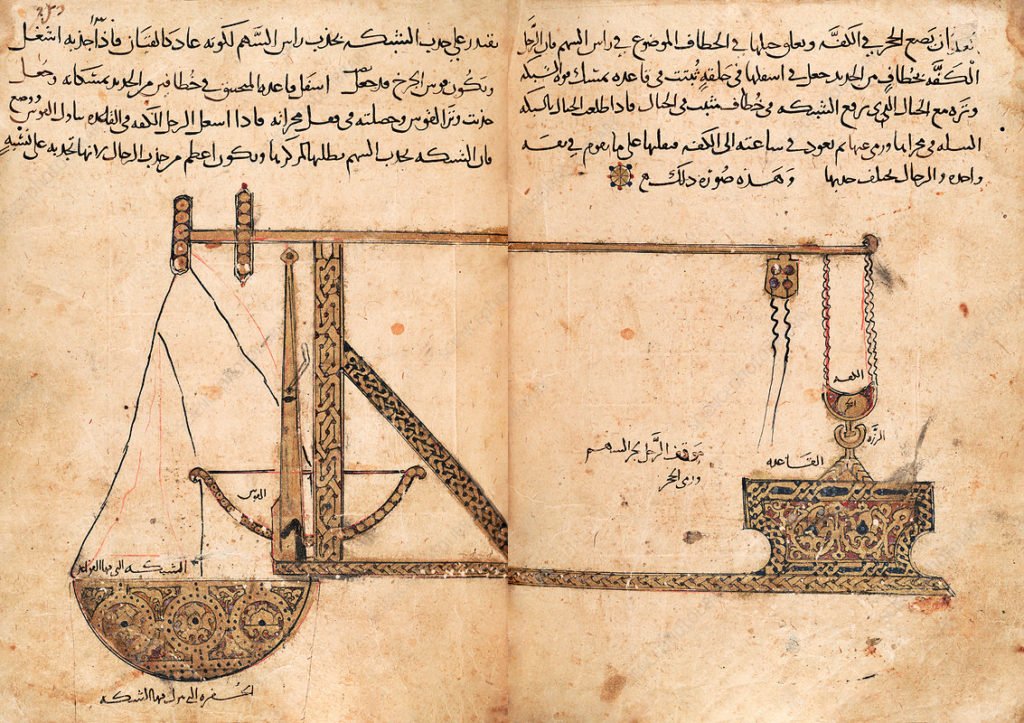

Earliest illustration of a manjaniq. Mardi ibn Ali al-Tarsusi, c. 1187 CE. 189

Why only Hejaz?

Just like the reporting of the First Arab Civil War, Islamic sources of the Second Arab Civil War are obsessed with events and personalities. They employ all of their eloquence to establish the innocence and righteousness of their favourites and meanness and indecency of the unfavoured. They leave it to the future historians to dig out the root cause of the trouble.

Noticeably, only people of Hejaz raised arms against the central government in the first phase of the Second Arab Civil War, more precisely Mecca and Medina. Taif remained neutral to some extent. The dissatisfaction of the people of Mecca and Medina toward the central government was only for one reason, according to Islamic sources. That was the immoral character of Yazid. The question is why only Hejazis were enraged. Were the Arabs of Basrah, Damascus or Fustat not Muslims? Arguably, there was something which hurt mainly the people of Mecca and Medina.

Let’s guess! When the rebels attacked Medina to dislodge Uthman in 656 CE, the caliph entered into an agreement with them. The central government gave a pledge that it will not pay stipends to anybody who did not participate in Futuhul Buldan except the bona fide Companions of the Prophet. We don’t find any sources for streaming money from the provinces to Mecca and Medina after it. Probably, the succeeding governments of Ali, Hasan and Mu’awiya honored the agreement. 195 Only a handful of the Prophet’s Companions kept receiving stipends. Most of them were residents of provincial capitals. Residents of the twin towns of Mecca and Medina were disgruntled with the situation.

The first phase of the Second Arab Civil War was a brawl between the factions of Quraysh for the highest chair. 196 Initially the unsatisfied population of Hejaz had a choice between Husayn and Ibn Zubayr. They were unsure of Husayn’s success, though. After his death, they embraced Ibn Zubayr wholeheartedly.

Slogans of the Second Arab Civil War

Each participating leader of the Second Arab Civil War knew that both possession of wealth and high number of supporters was key to final success. Tapping into the religious sentiments of the masses could indeed be a straightforward method to garner support. None of the participants in the Second Arab Civil War presented a clear political, social, or economic manifesto. Similar to the First Arab Civil War, all sides resorted to vilifying their opponents, questioning their adherence to the correct path of religion, in order to incite hatred against them. Yazid labels Ibn Zubayr mulhid, a man of deceit in religion, who slanders noble people. 197 Ibn Zubayr labels Yazid as “ a man who drinks wine, neglects his prayers, and goes hunting,” 198 Husayn states, ‘The [Yazid] government has make permissible what Allah had forbidden, violated Allah’s covenants, Opposed Sunnah of the Prophet by acting against servants of Allah sinfully and with hostility. They have neglected the punishments (ḥudūd) laid down by Allah’. 199

Defaming political opponents in religious terminology became a precedent in Muslim politics later on. There is not a single political movement after the Second Arab Civil War where opponents on both sides don’t blame each other for deviating from Islam. Such blames are usually vague, which means, religion remained the main ideological umbrella for political thoughts, and everybody tried to exploit it without being precise what he meant by his phrases. 200

Passions have played a significant role in shaping the political movements throughout history. The collective emotions of fear, hate, love, greed, and jealousy can be seen behind many historical changes. Most influential political books, like Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Gorky’s Mother were, anyhow, fictions not facts.

Kharijis during Yazid’s tenure

Mirdās bin ‘Amr had rebelled in Tawwaj during Mu’awiya’s reign. Ibn Ziyad, governor of Basrah, had sent two thousand men to punish him. He easily defeated the government forces. The matter was pending when Yazid came to power. Ibn Ziyad sent another force of three thousand men in 681 CE. Mirdas’s companions were inferior in number. They preferred death on the battle field to surrender. 201, 202.

The Khariji ideology smoldered throughout Mu’awiya’s tenure. Actually, according to statistics, thirteen thousand Kharijis were killed during combined tenures of Ziyad bin Abihi/Abu Sufyan and his son Ubaydullah bin Ziyad as governors of the Eastern Provinces. Four thousand Kharijis were thrown into prison by Ubaydullah alone.203 As Yazid took over and politics of the country took a violent turn, the Khariji ideology blazed.

In the fall of 681 CE, a few months after Ibn Zubayr proclaimed independence in Mecca, and when the revolt in Medina was simmering, the people of Yamama accepted Khariji doctrine en masse and raised a banner of revolt under their leader Najadah bin Amir of Hanifa.204 This was for the first time in history of Islam that whole population of a region accepted religious fundamentalism and managed a piece of land. The beleaguered Yazid government did not find any means to contain them.

Mawlas increase political activities

During Mu’awiya’s time, the political role of Mawlas was still that of subservient to the Arab catalyst who had symbolically freed them. 205 Mawlas were trustworthy in the eyes of the symbolic masters. They utilized them at times when they needed strict obedience. 206 As the Second Arab Civil War unfolded, the dynamics between Mawlas and their symbolic masters started changing. Apparently, hostilities among the ruling Arab Muslim elite had compelled them to depend upon Mawlas. By the time of Yazid, we can trace the latent political activism of individual Mawlas, independent of their symbolic masters. 207

Not only this, there is a shred of evidence that Christian subjects of the country had started taking interest in Arab Muslim politics as well. 208

Foreign policy of Yazid

Yazid’s brief tenure was full of internal strife. However, all internal events were of low intensity. Yazid never needed to withdraw troops from the borders to deploy them against his adversaries. Raids across the border continued in the Central Asian front.209 The situation was similar on the African front. 210.

The dependent territories of the Basrah province had been showing periodic hostilities against Umayyad Caliphate during Mu’awiya’s tenure. The trend continued. Khalifa mentions a revolt in Kabul in 682 CE in which they imprisoned Abu Ubaydah bin Ziyad bin Abihi/Abu Sufyan, the lieutenant governor of Sistan. Yazid bin Ziyad bin Abihi/Abu Sufyan went to fight against Kabul but was killed .211 In the fall of 682 CE Salm bin Ziyad bin Abihi/Abu Sufyan, the lieutenant governor of Khorasan, sent Talha bin Abdullah bin Khalaf of Khuza’ah to ransom his brother Abu Ubaydah bin Ziyad. He ransomed him for five hundred thousand dirhams. 212

The only eye-catching change in the foreign policy of the Umayyad Caliphate during Yazid’s tenure was regarding its relations with Byzantine Rome. Immediately after coming to power, Yezid deescalated the military buildup on the naval front. He ordered the destruction of the military installation and the withdrawal of troops from all Mediterranean islands including Cyprus. 213, 214 Yazid’s attempt to befriend his Christian subjects more than his predessors explains his attitude towards Byzantine Rome. Apparently, Byzantine Rome reciprocated the gesture. We don’t hear of any new infiltration of Byzantine Rome in the Rashidun Caliphate during Yazid’s tenure as it was customary during internal stife of the country before Yazid.

In general, border raids were not aimed at occupying territory; they served as a core strategy for the military of the Umayyad Caliphate. These raids persisted against Byzantine Rome at a consistent pace, much like they did during the rule of Mu’awiya. 215

Failure against ‘Meccan Alliance’

The last event of Yazid’s tenure, which heralded the downfall of Sufyanids, actually happened after Yazid’s death. The well-paid and well-armed huge army of Syrian Troops, despite its ferocity, failed to dislodge Abdullah bin Zubayr from Mecca. The siege was in its 60th day when the news of Yazid’s death reached Mecca. 216 The army was perhaps already fed up of hearing the chiding for attacking the sacred haram. 217 They halted the war, requested permission from Abdullah bin Zubayr to perform Umrah, and once the Umrah was completed, they promptly returned to Syria. 218 The illusion of the invincibility of the Syrian Troops, that kept provinces terrified for decades, fizzled out in two months. On their way back, the soldiers of Syrian Troops were so afraid of being looted by the emboldened residents of Hejaz that they had to stick together in groups.219, 220

Death of Yazid

Yazid was in the midst of his youth when he died. 221 His death was so sudden and unexpected that even his own soldiers disbelieved the news. 222 He was definitely not in a good shape of health. His opponents never got tired of accusing him of drinking alcohol, a charge which he always denied. 223 Tabari notes that he had gout and used to soak his feet in water to get cold/hot compression. 224 No source gives the cause of Yazid’s death. One can guess it could be a sudden metabolic event like cerebrovascular accident or myocardial infarction.

Yazid’s unanticipated death on the night of November 11, 683 CE, was a surprising twist in the drama of the Second Arab Civil War. 225 Yazid’s government was a house of cards which Yazid had been protecting against blows. Like some of his predecessors, Ali and Hasan, he never was recognized as a caliph by everybody in the country. Hejaz never came under his ambit properly. After the murder of Husayn, he developed an antagonism with the powerful governor of Eastern Provinces, Ubaydullah bin Ziyad. Ibn Ziyad anticipated that Yazid would dismiss him but Yazid never got in that position. 226 The Umayyad Caliphate was yet trying to establish a constitutional principle that the sitting caliph would have the sole right to nominate the next caliph. It was not widely accepted among Muslim Arab elite. They still expected that they had a right to give inputs in selection of a new caliph after the death of previous one. Yazid was grappling with the issue. The untimely death of Yazid collapsed the house of cards. 227 It opened crisis of replacement. The trouble hotbeds of the country, Hejaz, Kufa and Basrah plunged into disarray. And within a few days after Yazid’s death, the authority of central government shrank to environs of the Sufyanid palace in Damascus.

Ibn ‘Arādah said on Yazid’s death:

Oh Banū Umayyah, the end of your rule

Is a corpse at Huwwārīn, there remaining.

His fate came upon him while by his pillow

Was a cup and a wineskin filled to the brim and overflowing.

Many a plaintive singing girl weeps by his drunken companions,

With a cymbal, now sitting and now standing. 228, 229.

Yazid’s position in history

Out of all rulers of the Umayyad Caliphate the most notorious in political memory of later Muslim generations is Yazid. The murder of Husayn and assault on Ka’ba became his unforgivable crimes.230 He was only thirteen when Mu’awiya came to power. He might have been raised in a rich, worry-free environment. He had hobbies. His passion for music and pet dogs was obviously not palatable for pious Muslims. His political opponents took the full advantage to demonize his personality. 231

Anyhow, there is one aspect of his personality which becomes evident from an anecdote. Being well-versed in the Qur’an was customary among the early Muslim elites. People used to teach the Qur’an to their children at an early age. It does not astonish that young Ali bin Husayn was deft in knowledge of the Quran and could produce quotations from the sacred text in arguments with Yazid, when Ali faced the later in his court. Astonishing is that Yazid asked his second born, Khalid, to respond to him in terms of the Qur’an. It simply means that Yazid had taken pains to teach his children Quran and had expected from them to express it. When Khalid could not aptly bring any arguments, Yazid himself quoted from the Quran to snub Ali bin Husayn. It means Yazid himself was well versed in the Quran. 232

By the time Yazid came to power decorating Ka’ba, at least once, had become a symbol of sovereign’s attachment with Islam. 233 Yazid did his part. Accroding to Baladhuri, he covered the Ka’ba with Khusruwāni cloth.234 As Yazid’s government never had full authority over Ka’ba, it can be assumed that Yazid aquired the consent of Ibn Zubayr to do it.

Yazid adopted the same title of the ruler, which his predecessors had – Commander of the Faithful. He introduced himself by this title in his first official letter which he wrote to his governor of Medina to arrest opposition figures. Not only this, his letter had full Islamic format as the letters of his predessors had.235

Lastly, the comments of the anonymous chronicler of Spain writing in Latin in 741 CE: ‘a most pleasant man and deemed highly agreeable by all the people of his rule. He never, as is the wont of men, sought glory for himself because of his royal rank, but lived as a citizen along with all the common people.’236

History, as a modern science, seeks explanation of the events. Events are already known to everybody. Modern historians tend to look for the causes in fields like economics, geography, environment or technological changes. All of them do influence the events but they cannot explain each and every facet of an even. Yazid took over a popular, smoothly running and economically stable government. He left it in an impending chaos. Why and how? Were there any sudden economic, geographic, environmental or technological changes? We don’t find any. The only reasons we find, objectively, from the sources of the history of Yazid’s failures, are the perceived personal habbits of Yazid and religiosity of common people. Sentiments do play role in historical events. They are an independent factor, in addition to economics, geography, environment or technological changes.

End notes

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 2.

- Yazid started his reign on April 21, 680 CE. AND Khalifa Ibn Khayyat, Khalifa ibn Khayyat’s History on the Umayyad Dynasty (660 – 750), ed. and trans. Carl Wurtzel, (Liverpool, Liverpool University Press, 2015), P 109, Year 64. AND Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 930. See also: William Muir, The Caliphate; its rise, Decline and Fall, from Original Sources (Edinburgh: John Grant, 1915), 306.

- Yazid was born in 646 CE, fourteen years after the death of Prophet Muhammad. For the date, see: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. R. Stephen Humphreys (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 13.

- Yazid’s mother was Maysūn bint Haḥdal of Kalb tribe. (Khalifa Ibn Khayyat, Khalifa ibn Khayyat’s History on the Umayyad Dynasty (660 – 750), ed. and trans. Carl Wurtzel, (Liverpool, Liverpool University Press, 2015), P 111, Year 64 AND Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 226. AND Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 930).

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Michael G. Morony (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1987), 188.

- Islam doesn’t discriminate between the children of different wives. The debate was influenced by an Arab mindset rooted in tribal traditions. (William Muir, The Caliphate; its rise, Decline and Fall, from Original Sources (Edinburgh: John Grant, 1915), 304.)

- The assertion is confirmed by John bar Penkaye: “When Mu’awiya ended his days and left the word, Yazid his son reigned in his stead. He did not follow in the footsteps of his father”. (Sebastian P. Brock, “North Mesopotamia in the late seventh century: Book XV of John Bar Penkaye’s Rish Melle”, Jerusalem studies in Arabic and Islam, 9 (1987), 51 – 75)

- This coin is guessed to be from 61 AH (681 CE). Obverse has typical late Sassanian bust, i.e. profile portrait of Khosrow II, enclosed by double circle. On the left is written in Pahlavi script “GDH ‘FZWT (“Increase of Glory”). On the right, in front of the head a legend in Pahlavi “Ḥwslwy” (“Khosrow”) is written. On the obverse margin is the usual star-and-crescent ornament with a legend in Pahlavi ‘PD (“excellent”). The reverse has typical Sassanian fire-altar with attendants. The Pahlavi legend on the far left says: S.NT ‘YWK (“Year one”). On the far right it reads: Y YZYT (“Of Yazīd). No mint is mentioned on this coin. Worth noting is that the name Khosrow is not substituted with Yazid. It is also worth noting that there are no indications of Islamic characters on the coin. The Pahlavi “excellent” is not replaced with “Bism Allah”. (M. I. Mochiri, “A Sasanian-style Coin from Yazīd bin Mu’āwiya”, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, (1982): 137 – 141. Plate I.) The current location of the coin is unknown. For Hoyland’s comments on the issue see: Robert G. Hoyland, In God’s Path: the Arab Conquests and the Creation of an Islamic Empire (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 130.

- Archaeologists have discovered an inscription at Samrūnīyyāt about 12 km south-west of Qaṣr Burqu’ in modern Jordan. It is probably written by a Christen soldier of Yazid. The inscription reads, ‘Yazid the king’. (Younis al-Shdaifat, Ahmad Al-Jallad, Zeyad al-Salameen, Rafe Harahsheh, “An early Christian Arabic graffito mentioning ‘Yazīd the King’ ”, Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy, Vol 28, Issue 2 (November 2017): 315 – 324. Fig. 1.) As a graffiti sheds light on what transpired in the mind of a person at the time of writing, it is apparent that the soldier was proud of his king.

- Younis al-Shdaifat, Ahmad al-Jallad, Zeyad al-Salameen, and Rafe Harahsheh, “An Early Christian Arabic Graffito Mentioning ‘Yazīd the King’,” Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy 28 no. 2 (2017): 315 – 324.

- “The strength of [Arab] men declined under his[Yazid’s] weak government,” analyzes John bar Penkaye. (Sebastian P. Brock, “North Mesopotamia in the late seventh century: Book XV of John Bar Penkaye’s Rish Melle”, Jerusalem studies in Arabic and Islam, 9 (1987), 51 – 75)

- Khalifa Ibn Khayyat, Khalifa ibn Khayyat’s History on the Umayyad Dynasty (660 – 750), ed. and trans. Carl Wurtzel, (Liverpool, Liverpool University Press, 2015), P 93, year 60 AND Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 2. AND Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 930

- Abdur Rahman bin Abu Bakr had died by that time. He died in 673 CE. (Khalifa Ibn Khayyat, Khalifa ibn Khayyat’s History on the Umayyad Dynasty (660 – 750), ed. and trans. Carl Wurtzel, (Liverpool, Liverpool University Press, 2015), P 76, year 53).

- Initially, Abdullah bin Umar responded to Walid’s messenger that when everybody else gives oath he would give it as well. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 9). Later on, when the provinces had pledged allegiance to Yazid he also gave allegiance. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990),10.) Abdullah bin Umar was a soldier by trade In this capacity, he participated in the campaign of Tabaristan in 651 CE under the command of Sa’id bin As. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. R. Stephen Humphreys (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 42. During the later years of his life, Abdullah bin Umar turned more towards religion and Tabari describes him as a pious person who did not have any interest in worldly matters. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Michael G. Morony (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1987), 208).

- Only those participate in the race to the ‘White House’ who have a glimmer of hope of reaching the finish line. Abdullah bin Umar had no political supporters in the country – thanks to selfless service of his father to the country.

- Abdallah bin Zubayr had always been a person with political bend. He attended the proceedings of the arbitration between Ali and Mu’awiya enthusiastically. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 107). His trade was soldiers. He had participated in the campaign of Tabaristan under the leadership of Sa’id bin As during Uthman’s tenure in 651 (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. R. Stephen Humphreys (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 42). He was active in the military of the Umayyad Caliphate as well and in this capacity he fought on the Byzantine Rome front under the command of Yazid in 669 CE. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Michael G. Morony (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1987), 94).

- Husayn bin Ali was the secondborn of Ali bin Abu Talib. When Husayn came of age, he joined the military of the Rashidun Caliphate as a soldier. In this capacity, he participated in the campaign of Tabaristan under the leadership of Sa’id bin As in 651 CE. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. R. Stephen Humphreys (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 42.). He got involved in the politics of the country later on and participated in the Battle of Siffin from Ali’s side. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 41). He was an advisor to his brother Hasan after the death of his father, Ali. He was totally opposed to Hasan’s policy of reconciliation with Mu’awiya. He implored his brother and warned him not to believe Mu’awiya’s story and advised him to believe the story of Ali at a time when Hasan was at the verge of surrendering his claim to the caliphate. Hasan had to snub him, saying he didn’t know as much as Hasan did. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Michael G. Morony (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1987), 5). Husayn had pledged allegiance to Mu’awiya as part of the peace deal signed with Hasan. Since then, he had taken residence in Medina.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 3, 4, 5.

- Khalifa Ibn Khayyat, Khalifa ibn Khayyat’s History on the Umayyad Dynasty (660 – 750), ed. and trans. Carl Wurtzel, (Liverpool, Liverpool University Press, 2015), P 94, 95. Year 60 AND Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 6, 7. AND Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 931. See also: G. R. Hawting, The First Dynasty of Islam, (London: Routledge, 2000), 47).

- Husayn reached Mecca on May 9, 680 CE. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 64, 84). It took five nights to complete a journey that should have taken only two. Clearly, he was trying to avoid arrest by staying off the radar of government spies.

- For dismissal of Walid bin Utba see: Khalifa Ibn Khayyat, Khalifa ibn Khayyat’s History on the Umayyad Dynasty (660 – 750), ed. and trans. Carl Wurtzel, (Liverpool, Liverpool University Press, 2015), P 90, year 60. ‘Amr bin Sa’id bin As was governor over Mecca at the time of Mu’awiya’s death. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 2. One source of Tabari gives the date of dismissal to be June 680 CE, other sources give it July 680. See: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 10, 15, 90.

- Walter, Kaegi E.. Byzantium and the early Islamic conquests. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 243

- G. R. Hawting, The First Dynasty of Islam, (London: Routledge, 2000), 46

- For a detailed description of the Second Arab Civil War see: Gernot Rotter, Die Umayyaden und der zweite Burgerkreig (680 – 692) (Wiesbaden, 1982). AND R. Sellheim, Der zweite Burgrerkrieg im Islam (680-962), Extrait des Sitzungsberichte der Wissenschaftlichen Gesellschaft an der J. W. Goethe-Universitat Frankfurt/Main, VIII/4, 1969, pp. 87 – 111, Weibaden 1970. Another work that deals with it is: ‘Abd al-Ameer ‘Abd Dixon, The Umayyad Caliphate, 65 – 86/684 – 705: (a political study), (London: Luzac, 1971).

- Unlike the First Arab Civil War, the descendants of Talha bin Ubaydullah were junior partners in the ‘Mecca Alliance’. Ishaq bin Talha bin Ubaydullah had died in 676 CE. Khalifa Ibn Khayyat, Khalifa ibn Khayyat’s History on the Umayyad Dynasty (660 – 750), ed. and trans. Carl Wurtzel, (Liverpool, Liverpool University Press, 2015), P 83, Year 56. Ibrahim bin Talha became a member of the ‘Mecca Alliance’ under the leadership of Ibn Zubayr. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989) 92, 93. )

- When Husayn left Mecca for Kufa, governor ‘Amr bin Sa’id sent messengers to him as a last ditch attempt to prevent Husayn from his designs. The messengers reiterated Yazid’s stand and warned Husayn to fear Allah and leave the people unified (jamā’ah) and don’t split this community (Ummah). (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 70). Similarly, ‘Amr bin Ḥajjāj was a supporter of Yazid, fighting against Husayn and his companions. Before the battle started he expressed the political stand of ahl al Jami’ah in the presence of the followers of Husyan. He said, “People of Kufa! Stay steadfast in your obedience and unity (Jamā’ah). Do not have any doubts about fighting against those who have strayed from the true religion and have opposed the imām.” (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 137). The godfather of Ahl al Jami’ah was Uthman bin Affan. When the news of Husayn’s death reached Medina through a messenger sent by Ubaydullah bin Ziyad to ‘Amr bin Sa’īd bin ‘Ās, governor of Medina, the women of Banu Hashim lamented bitterly. ‘Amr bin Sa’id laughed and said this lamentation is in return for the lamentation for ‘Uthman bin ‘Affan. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 177)

- See the contents of the letter Husayn wrote to his supporters in Basrah. He outlined his political philosophy in this letter. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 31, 32). When the forces of Ibn Ziyad halted Husayn on the fringes of Kufa and negotiations started, Husayn claimed that he had more right to correct things because he was Husayn bin Ali, the son of Fatima, the daughter of the Prophet. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 96.

- While talking to Husayn in Mecca, Ibn Zubayr claimed that only the sons of the early Muhajirun had the right to govern the country. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 67.).

- Hawting comments, “Ibn Zubayr does not seem to have espoused any distinctive religious or political program in the manner of the Shi’ites and the Kharijites (we are told that his alliance with the kharijites foundered when he refused to accept their religious and political program), and it seems that he won support mainly because of his status as one of the first generation of Muslims and a member of Quraysh at a time when the Umayyads were weak and opposition to them strong in different quarters. One thing that is notable, however, is the strong association between him and the Muslim sanctuary at Mecca. (G. R. Hawting, The First Dynasty of Islam, (London: Routledge, 2000), 49).

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 89.

- On reaching Mecca, Ibn Zubayr simply requested Ḥārith bin Khālid of the Makhzūm clan to stop leading the prayers. He complied. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 11.).

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990),11

- Amr bin Sa’id had already put Amr bin Zubayr in charge of his police in Medina because Amr bin Sa’id was aware of enmity between the two brothers. Amr bin Zubayr flogged a group of people in Medina who were supporters of Ibn Zubayr. Those who got flogged included Mundhir bin Zubayr, (Abdullah bin Zubayr’s brother), Mundhir’s son Muhammad bin Mundhir, Khubayb bin Abdullah bin Zubayr, and Muhammad bin ‘Ammar bin Yāsir (see how party changed). Each of them got forty to sixty lashes. The few supporters of Ibn Zubayr could escape to Mecca unharmed (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 11, 12).

- Both Husayn and Ibn Zubayr entered into negotiations about who would rule Mecca and later the country in future political set up. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 69.)

- Khalifa Ibn Khayyat, Khalifa ibn Khayyat’s History on the Umayyad Dynasty (660 – 750), ed. and trans. Carl Wurtzel, (Liverpool, Liverpool University Press, 2015), P 94, 95. Year 60. AND Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 23

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 67.

- The political case of the ‘Meccan Alliance’ was the weakest. The stance of Ahl al Jami’ah, that the unity of Ummah was of utmost importance and whoever governs the country is of secondary significance, appealed to many. Similarly, the stance of Shi’a Ali that the family of the founder of religion has the first right to govern over a country that had come into existence as a result of founding of religion, was valid in eyes of many. Ibn Zubayr’s only option was to play the ‘religious card’ to attract support. John bar Penkaye notes, “Zubayr made his voice heard from afar. He said of himself that he had come out of zeal for the house of God. He threatened the west [Umayyads], as transgressors of the Law. So he went south, into the place where was their place of worship, and settled there.” (Sebastian P. Brock, “North Mesopotamia in the late seventh century: Book XV of John Bar Penkaye’s Rish Melle”, Jerusalem studies in Arabic and Islam, 9 (1987), 51 – 75). It appears that Husayn did not consider the idea of using the sanctuary as a shield and get killed there in case of defeat as morally justifiable. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 69. AND Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 941.)

- According to Tabari, the force that went to Mecca against Ibn Zubayr consisted of a few dozen men on the dīwān, many mawlas of people of Medina and seven hundred men of Aslam. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 12). For the total number of soldiers see: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 16.

- For the government’s debate on whether or not to raid the sanctuary see: al-Waqidi’s Kitab al-Maghazi.; The life of Muhammad, edited by Rizwi Faizer, translated by Rizwi Faizer, Amal Ismail, Abdulkader Tayob. Routledge New York 2011; 415. See also: Khalifa Ibn Khayyat, Khalifa ibn Khayyat’s History on the Umayyad Dynasty (660 – 750), ed. and trans. Carl Wurtzel, (Liverpool, Liverpool University Press, 2015), P 95, Year 60 AND Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990),12, 13, 16

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 13, 14.

- The force that came to dislodge Ibn Zubayr had no coherence. The official police and tribal lashkar of Aslam fought separately. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 13. The reluctance to raid the sanctuary was at the minds of official policemen. Their commander, Amr bin Zubayr, sent a message to Abdullah bin Zubayr just before the start of war to surrender and avoid fighting in the sacred city. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 13). The secondary audience for this message might include his own men, whom he wished to persuade that it was Ibn Zubayr who had created a situation where a raid on the sanctuary was unavoidable.

- One of the commanders of Ibn Zubayr’s forces was Muṣ’ab bin Abdur Rahman bin Awf) (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990),14). Mus’ab’s appearance here gives a clue how alignment of the Second Arab Civil War was. Mus’ab bin Abdur Rahman died during the siege of Mecca by end of 683 CE. Khalifa Ibn Khayyat, Khalifa ibn Khayyat’s History on the Umayyad Dynasty (660 – 750), ed. and trans. Carl Wurtzel, (Liverpool, Liverpool University Press, 2015), P 111, Year 64

- Unays bin Amr, the leader of Aslam portion of the forces of the provincial government, was killed in the campaign. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 16). Amr bin Zubayr, the overall commander of the forces of the provincial government, was arrested alive. Abdullah bin Zubayr initially imprisoned him, and then asked his Medinite supporters to flog him as many times as they were flogged in retaliation. Amr bin Zubayr could not endure the extensive flogging and died. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 16. AND Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 964). Apparently, Zubayrid’s supporters had reached Medina from Mecca and they took vengeance physically.

- Husayn was born in 625 CE. (Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 936. Tabari states his age as fifty-five. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 82. Ya’qubi gives his age at death as fifty-six. (Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 936

- For the presence of a strong group of Shi’a Ali in Yemen see: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 67

- For activities of Shi’a Ali in Basrah see: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 26, 27, 36.

- Husayn did not limit his appeal to Shi’a Ali. He also tried to win over prominent members of the neutral party. See, for example, his letter written to Ahnaf bin Qays in Basrah. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990),32.

- For the date see: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 25

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990),16, 17. AND Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 931

- It seems that Husayn lacked confidence in the strength of his support in Kufa, as he requested Muslim to go there and verify the accuracy of the reports. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990),17, 26, 27). There are reports that many of Husayn’s sympathizers did not trust in loyalty of Kufans. They were of the view that Shi’a Ali of Kufa loved the glitter of Dirhams and Dinars more than they loved Husayn. They were government employees and their support to Husayn was just lip service. Those who were promising to fight with Husayn might fight against him when the time comes. For such comments from Husyan’s sympathizers in Mecca see: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 66).

- Muslim bin Aqil was a young man. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 55

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 8, 83.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 67

- The shakiness of Shi’a Ali of Kufa was apparent to many political observers. Some of those political observers were sympathizers of Husayn. Farazdaq, for example, commented that the hearts of the people were with Husayn but their swords were with Banu Umayya. (Khalifa Ibn Khayyat, Khalifa ibn Khayyat’s History on the Umayyad Dynasty (660 – 750), ed. and trans. Carl Wurtzel, (Liverpool, Liverpool University Press, 2015), P 93, year 60. AND Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 71).

- Suggestions to Husayn for his future line of action were numerous. Someone advised Husayn to go to the territory of Tayy and organize a rebellion with their help. Their mountains had defended them against Ghassan, Himyar and Nu’man bin Mundhir, he said. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 99, 100)

- Soon after, Abdullah bin Abbas pledged allegiance to Yazid. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 10). He took retirement from active politics and took up residence in Taif. (Khalifa Ibn Khayyat, Khalifa ibn Khayyat’s History on the Umayyad Dynasty (660 – 750), ed. and trans. Carl Wurtzel, (Liverpool, Liverpool University Press, 2015), P 124, Year 68.). Probably he chose Taif because he might have inherited the vineyard from his father.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 89.

- For the date of the departure of Husayn to Kufa see: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 64.

- Abdullah bin Amr bin As was in Mecca by the time Husayn left Mecca. He sympathized with Husayn but he didn’t accompany Husayn. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 71, 72.). Abdullah bin Amr’s tug-of war had continued with Mu’awiya after former’s dismissal as governor of Egypt. Abdullah bin Amr had an estate in Taif. Mu’awiya had offered to buy it above market price but Abdullah refused. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 71, 72.). This is the last entry of Abdullah bin Amr in the history of Islam. After him, the family of Amr bin As disappeared in anonymity.

- According to Muslim’s assessment, a majority (jam’) of Kufa was with Husayn. See: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 84.

- Khalifa Ibn Khayyat, Khalifa ibn Khayyat’s History on the Umayyad Dynasty (660 – 750), ed. and trans. Carl Wurtzel, (Liverpool, Liverpool University Press, 2015), P 92, Year 60. AND Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990),17, 30, 47. AND (Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 931.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 42

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990),17, 29.

- Governor Nu’man bin Bashir was not a sympathizer of Husayn. He was reluctant to crack down on the potential rebellion on the grounds that nobody had yet defied government authority. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990),29). He remained loyal to the Yazid government (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 36) and acted as Yazid’s ambassador to the revolting Medinites later (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 199,200)

- Kufa had a population of forty thousand (see above). Out of them, only eighteen thousand had assured Muslim bin Aqil of their support to Husayn.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990),17, 30.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 18, 31.

- Khalifa Ibn Khayyat, Khalifa ibn Khayyat’s History on the Umayyad Dynasty (660 – 750), ed. and trans. Carl Wurtzel, (Liverpool, Liverpool University Press, 2015), P 92, Year 60.

- Ubaydullah bin Ziyad was the son of late governor Ziyad bin Abihi/Abu Sufyan. He was born and raised in Basrah. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 7). He was a young man, just twenty-five, when Mu’awiya appointed him as lieutenant governor of Khorasan in 674 CE after death of his father. (Khalifa Ibn Khayyat, Khalifa ibn Khayyat’s History on the Umayyad Dynasty (660 – 750), ed. and trans. Carl Wurtzel, (Liverpool, Liverpool University Press, 2015), P 76, 77, Year 7. AND Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Michael G. Morony (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1987), 175. AND Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 917). He served as the lieutenant governor of Khorasan for two years. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Michael G. Morony (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1987), 179). He was a successful lieutenant governor and is reputed to have raided Bukhara, Ramithan and Baykand successfully. (Khalifa Ibn Khayyat, Khalifa ibn Khayyat’s History on the Umayyad Dynasty (660 – 750), ed. and trans. Carl Wurtzel, (Liverpool, Liverpool University Press, 2015), P 80, 81. Year 54. AND Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Michael G. Morony (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1987), 178, 179. AND Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 918). Mu’awiya was so happy with the efficiency of Ibn Ziyad that he gave him governorship of the largest province of the country – Basrah, in 675 CE. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Michael G. Morony (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1987), 180. AND Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 918). He served as governor of Basra until Mu’awiya died and Yazid took over. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Michael G. Morony (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1987), P 82, Year 55. See also: G. R. Hawting, The First Dynasty of Islam, (London: Routledge, 2000) 40.). Name of Ubaydullah’s mother was Marjānah. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 36.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 18, 36

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 20, 20. AND Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 932

- It was the same day, September 9, 680 CE, on which Husayn left Mecca for Kufa. See: (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 64, 84.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 20, 20.

- For the tribal affiliation of Hani’ and how Muslim ended up in his house see: (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 18).

- Ubaydullah was with only thirty policemen and ten Ashraf and his own family when he barricaded himself in the mosque. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. I. K. A. Howard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 48)