Economic conditions prevalent during the Umayyad Caliphate were entirely different from those of its precursor, the Rashidun Caliphate. Generally speaking, the economy of the Rashidun Caliphate was that of uncertainty while the economy of the Umayyad Caliphate was that of stability mixed with intermittent interruptions of uncertainty.

Gross domestic product

Any group/country whose income is growing is progressive. Any group/country where income is stagnant is conservative. Any group/country where income is decreasing is reactionary. It is challenging to allot the Umayyad Caliphate to any of these categories. Data is not sufficient. The economy of the country, and thus the GDP, must have fluctuated tremendously during the length of the Umayyad Caliphate. Praise for economic growth during Mu’awiya bin Sufyan’s two decades has reached us. 1 Relative peace gets credit for it. Ten years of the Second Arab Civil War must have damaged the economy. It might have become stagnant if not in recession. The economy must have recovered from the setbacks of war and stabilized during the ten years of Abdul Malik. It might have actually grown steadfastly during the combined tenure of Walid and Sulayman. The lengthy twenty years of Hisham must have seen a stable economy but a shift in the Gini coefficient towards the higher side. It gave rise to civil unrest that actually took the Umayyad Caliphate’s life.

Agriculture

Agricultural development was the main contributor to economic growth. The government allotted uncultivated lands free of cost. The private sector developed them.

Much of Iraq’s agricultural land was laid waste due to government negligence during the Sasanian Civil War. 2 The Rashidun Caliphate did not get the time and resources to rehabilitate it. The Mu’awiya bin Abu Sufyan government started the pending work. Almost all of these lands were crown property. They included wastelands, swamps, ditches and thickets. Mu’awiya appointed his Mawla ‘Abdullah bin Darrāj to reclaim them. Abdullah cut down the reeds, made dykes to stop water and made them arable. The action generated five million dirhams in annual income for the government. Later on, the Hajjaj government completed the project during Walid bin Abdul Malik’s tenure. Hajjaj uprooted further weeds, built irrigation dams (musannayāt) and populated the lands. 3

One particular area was very low-lying. Breaches in the canal filled it with water. Hajjaj estimated a cost of three million dirhams to Walid bin Abdul Malik for reclaiming this land. Walid did not see any value for money in the endeavor. Maslamah bin Abdul Malik saw an opportunity. He offered Walid to invest that much money provided Walid allotted the land to Maslamah as a fief. Walid agreed, provided Maslamah spent the agreed money under the supervision of Hajjaj so actual spending could be verified. Maslamah signed the deal. As a result, Maslmah got a large tract of fertile land. He dug a canal to provide water. He induced farmers and tenants to come and hold this land. 4

Balis and the villages attached to it on the upper, middle and lower extremities of the Euphrates were watered only by rain. They were simply tithe-lands. Maslamah bin Abdul Malik bin Marwan happened to camp at Balis on his way to the expedition against Byzantine Rome. He saw potential. He dug a canal and converted the land into irrigable fields. The farmers using the canal water had to pay Maslamah one-third of their crop, in addition to the usual tithe they used to pay the government (sultan). 5

Umar bin Khattab government had started a canal-digging project in the Anbar region of Iraq in response to the demands of local landlords. Governor Sa’d bin Waqqas shelved the project when a difficult-to-excavate mountain hindered further digging. The provincial government of Hajjaj started it from where Sa’d bin Waqqas had left it. The Hajjaj government spent more than usual money to complete it. Interestingly, during the pilot project to assess the economic viability of the canal, Hajjaj ordered to check if one worker could produce as many results as he ate. 6

Land development was not limited to high-ups in the government. The peripheral Umayyads had their own shares in this activity. Abdullah bin Amir bin Kurays, Mu’awiya’s governor of Basrah is also known to have indulged in such activities. 7

Manufacturing

It is an open secret that the most significant economic sector of the Umayyad Caliphate was agriculture. Manufacturing was, however, not much behind.

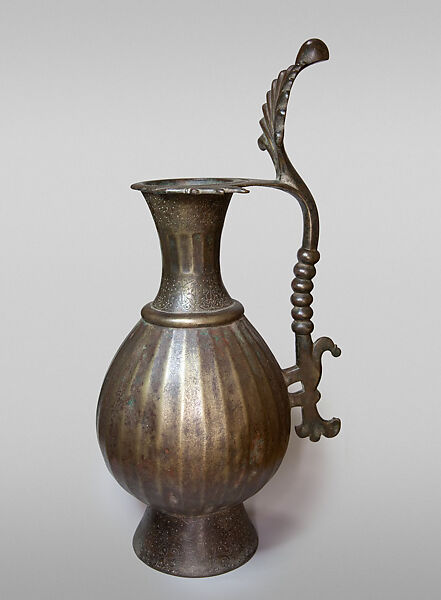

An interesting piece of metal is preserved in the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. It is the upper portion of a bronze can. The rim of the can has an inscription, “Made in Baṣrah in year sixty-nine, ‘barakah’ crafted by Ibn Yazīd.” 8 Basrah was the center for metallurgy in 688 CE and a certain Arab company by the name of Ibn Yzid mastered the art to the extent that it became a brand name.

Bronze jug with inscription.9

As rulers had a right to run their own businesses, they could use government regulations to promote their business interests. Such endeavors might have impacted the business environment negatively. Acre was an industrial hub in Jordan. A certain Arab family owned many mills and workshops in Acre. Caliph Hisham bin Abdul Malik offered to buy their businesses. The Arab family refused. Hisham used government regulations to move all of the industry (ṣiḥ’ah) of Jordan to Tyre, depleting Acre of its businesses. Then Hisham opened his own inn and a workshop in nearby Tyre. 11

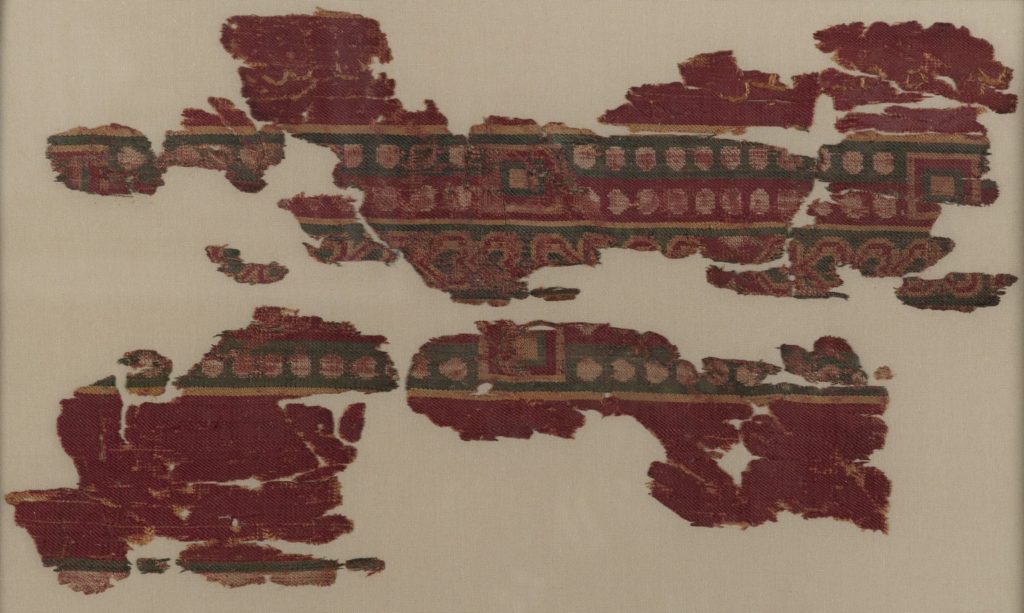

Despite the negative impact of government policies on the industry, businesses flourished. One reason could be the high aggregate demand during peaceful intervals. The demand for textiles was so great and competition among the manufacturers was so healthy that new concepts had to be presented in the market. One such innovation was the knitting of ṭirāz. Tiraz was actually an inscription in a piece of textile. The inscription could be anything but it was usually the name of the owner of that particular dress. Tiraz assured the onlookers that a particular dress was specifically customized for a certain individual. One cloth inscription is embroidered in a split stitch, with yellow silk on the red ground. Before being sown, the inscription was dotted with ink on the fabric. It exists in three pieces. The piece preserved in the Victoria and Albert Museum contains Caliph’s name. The piece in Whitworth Art Gallery Manchester contains the words “in the ṭirāz factory of Ifriqiyah.” The third piece is in the Brooklyn Museum, New York (41.1265). The fourth uninscribed piece is in Musee Royaux des Arts Decoratifs in Brussels. The combined pieces read, “[The servant of] Allah, Marwān, Commander of the Faith[ful]. Of what was ordered [to be made by] al-R … (or al-Z …) in the ṭirāz of Ifriqiyah.” 12 Tiraz was not limited to the extremely rich. The middle class could afford it. A tiraz preserved in the Museum of Islamic Art, Cairo and manufactured in 707 CE belonged to a certain Samuel bin Musa.13 This Samuel might have been a Jewish or a Christian person.

Service sector

As an economy grows, the service sector becomes the major portion of GDP. It creates more jobs than any other sector of the economy. The service sector of the Umayyad Caliphate was not that big. Still, it was significant. A lot of working people were involved in the service sector. Renting riding animals was a big business as long-haul travel had increased. Smith’s street in Kufa was a special market for renting riding animals during Mukhtar’s time. 14 As travel increased, renting accommodations to tourists became a lucrative business. This was particularly true for Mecca, where numberless religious tourists flocked to the city all year long. 15 Here again we can find easily government intervention in the market with a negative impact. The government actively discouraged people from buying services and goods from its political opponents.16

Trade and merchandise

Trade flourished throughout the Umayyad Caliphate. Most documented is the China-Iraq trade in luxury goods. Many traders on the China Merv route were Turks. 17 Probably, the Arabs bought from them and took the goods to further western markets.

The trade was over land as well as through sea. Ḥassān bin Nabaṭi managed to build a lighthouse (manārah) at Basrah port. 18 It was a government initiative to improve the infrastructure to promote trade and travel.

Mining

Historical sources are rich in mentioning a substance that could burn easily and helped to burn other objects. They call it nafṭ (tar or naphta). The way people used to pour it over a material before setting it to fire leaves no doubt that it was crude mineral oil. 19 As we don’t hear of any digging of wells to get naft, one can assume that it was available on the surface.

Economic Infrastructure

Traditionally, investing in economic infrastructure is the most applauded policy of a government. It enhances public satisfaction with the government because the facilities created not only serve the business but also the general public. The governments, on their part, boast about the completed projects to cash in on the goodwill a project generates. The Walid II government, despite its short duration, built a permanent bridge on Massisah – Adana road about nine miles from Massisah in 743 CE. It was still called bridge of Walid (jisr al Walīd) when Baladhuri wrote his monograph. 20, 21

Postal system

A good communication system is a prerequisite for nationwide trade and effective governance. The postal system was complete and mature in the Rashidun Caliphate. The Umayyad Caliphate maintained its quality. The official barīd system was accessible to common people. They could even send a letter to the ruler. 22

Borrowing and lending

Financing one’s business or other needs through lenders was a common practice. Lending and borrowing was a legal business performed under written contracts duly witnessed by two persons. P. Louvre Inv. E 7106 is a debt acknowledgement written on a piece of leather-dated the fall of 664 CE. It is witnessed by two males. The indebted is a woman by the name of Tarīs bint Muqayr who has borrowed a third of dinar. Though the document is on a small piece of leather with very little space, there is no mention of any interest. 23 Other similar documents do exist in libraries and museums. 24 None of them mention interest.

Borrowing and lending was not an opportunistic activity. There existed people of repute in the society who acted as bankers. A non-Arab by the name of Fayrūz Ḥusayn had participated in the Rebellion of the Commons against the sitting government. His kuniyah ‘Abu ‘Uthmān’ gives a hint that he was a Mawla. He was arrested and tried in the court of Hajjaj. The court asked him to explain his conduct of participation in an Arab dispute while being a non-Arab. The court rejected his defense that it was a sedation in which everybody caught up including non-Arabs. He got the death sentence. It came to be known that many people owed money to Fayruz. Fayruz had to compile a list of his property with the help of his servant (ghulām). Then the court compelled him to stand at the city gate and announce to a group of people his readiness to clear his debts. He had to return all his debts before his execution.25 It is clear from the story that Fayruz Husayn was a banker. He had accounts of several people with him. It is also clear that the bank was a person, not an institute. The banker’s death could make his debts uncollectable.26 If lending was that risky and really without any profit, what incentive did people have in taking a risk to lend their savings?

Many times, disputes around lending and borrowing would lead to violence. In one such instance, a rich Arab creditor from Hamedan attacked and choked a merchant to death because the merchant owed money to the Arab and was reluctant to pay. The rich Arab ended up in jail at Kufa. 27 Not all lenders were that hot-minded. When a soldier was unable to pay his loans, his creditors complained to the government and had him arrested. His friend paid his debt to ensure his release. 28 If creditors had to go to the extent of imprisonment or even murder of the indebted, there should be a strong incentive for creditors to lend money. None of the historical sources mentions any incentive. All of them keep us in suspense about the incentive behind lending.

Documented economy

The Centre of Papyrological Studies and Inscriptions (ACPSI), ‘Ain Shams University in Egypt lodges a business letter written in Arabic. Only nine complete lines have survived. It appears to be a business communication between a cloth merchant and his agent or partner. The letter says, “Qays ibn Hijr, and as far for the clothes, the market is more stagnant than I have ever seen it, and with one raṭal [pound] and half of pepper. And you [have] written to me concerning the subject of the eight dīnārs for the price of the ‘izār [waist wrapper] which is due from Hānī’ ibn Namir. Well, they claimed that you have already received them [i.e. dinars]. Peace be upon you and Allah’s mercy. And the gold that you have sent with Qays ibn Ḥajar is for part of the price for the three clothes which are with Qays ibn Ḥajar and for the garment which is my entitlement for the Ḥajj [pilgrimage].” Hanafi assigns the first Islamic century to the papyrus.29

The Umayyad Caliphate ran more or less a documented economy. Even bribery and gifts were duly documented. That is the reason details have survived. The government also maintained its books properly. When Kirmani got control of Merv, a man from Bukharis of the town came to Muqātil bin Sulayman, the administrative assistant, claiming that the government owed him money because he had set up mangonels. Muqatil asked him to establish proof thereof that he had done it for the sake of Muslims. He brought the testimony of Shaybah bin Shaykh al Azdi. Only then a draft on the treasury was written for the man at Muqatil’s behest.30

Safety

The rulers of the Umayyad Caliphate knew without any doubt that maintaining law and order in the country was a government responsibility. The conditions in which a woman could travel alone were a gold standard to measure the level of personal safety. Praising the safety of his roads, Qutayba bin Muslim boasts during the government of Walid I that the roads are so secure that a woman can travel in a litter from Merv to Balkh without an escort. 31

The Umayyad Caliphate met this standard on occasions, on others, it did not. Looting and robbery became widespread whenever the government got weak. Cutting off land revenues from reaching the government’s hands was the main source of income for the Khariji leader Shabib. 32 Anybody could be a victim of robbery. Once Yazid bin Muhallab, the son of the lieutenant governor of Khorasan, was on his way from Kish to Merv in the summer of 701 CE during the early years of Walid I, along with sixty equestrians. The party encountered some one hundred and fifty Turk dacoits in the desert of Nasaf. The dacoits demanded ‘anything’. The Muhallab party did not disclose their identity to the dacoits, probably to avoid being taken for ransom. Rather they posed to be merchants and told the dacoits that they had already sent their merchandise ahead of them. The party gave the dacoits a garment, some pieces of clothes and a bow. The dacoits went away, but apparently, they were not satisfied and returned demanding more. Yazid got annoyed and decided to fight against them. The fight did not push the dacoits away. The dacoits were determined to fight to their death. Yazid’s companion asked Yazid not to risk his life because his brother Mughirah had just died and his father Muhallab was still in shock from that death. Yazid said, “Mughirah did not exceed his allotted time span, and I shall not exceed mine.” His companion Muhhā’ah threw a yellow turban toward the dacoits. They took it and departed. One of the companions of Yazid by the name of Abu Muhammad al Zammi fled from the scene when he saw the dacoits. When the situation got clear, he returned with some horsemen and food. Yazid complained to him that he had deserted them. He answered that he had gone to get reinforcements and food. 33

The highways of Khorasan were infested with dacoits during the early years of Walid I but they were relatively safe during later years when Qutayba was the governor.

State sponsored safety networking

After the post Second Arab Civil War military, administrative and financial reforms, the central government had surplus money to attend to other state needs. Government handouts are always very popular. They help a ruler in enhancing his profile. The masses support them, turning a blind eye to the ruinous economic results of such policies. Very few people dare to criticize a government over this. Walid bin Abdul Malik was the first to establish hospitals (bīmāristān) for the sick, free food banks (dār al- ḍiyāfah), and a grant stipend to the blind, poor, and lepers. 34 He started paying government funds to all those afflicted with elephantiasis, telling them not to beg from the people. He provided every crippled with a servant and every blind with a guide. 35 Later on, in 707 CE, Walid ordered Umar bin Abdul Aziz to make the mountain passes of Hijaz easier and to dig wells at Medina. He ordered the construction of a drinking fountain at the Mosque of the Prophet. When Walid made the pilgrimage, he stopped at it, looked at the building and drank from the fountain. He ordered that it should have superintendents to look after it and the people of the mosque should be allowed to drink from it free. 36 After that the tradition continued more or less throughout the Umayyad Caliphate depending upon the funds available to the central government and its stability.

Private philanthropists played a vital role in the redistribution of money. Maslamah bin Abdul Malik owed a piece of income-producing land in Baghrās. He gave it as an unalienable legacy (waqf) to be used in the cause of righteousness. 37, 38

Prices

The time length of the Umayyad Caliphate was almost one century. Its provinces were varied. The fiscal policy of the government changed many times. Intervals of both peace and war affected the country many times. The surviving price data in historical sources might be misleading to draw general conclusions. It appears the most fluctuating prices in the Umayyad Caliphate were those of staple food. The reason was the delicate supply chain. Whenever a crisis came, when there was a famine or a war, the prices of staple food skyrocketed. At other times, they remained at baseline. They never dropped below the baseline. There was not an abundant supply at any time. The prices of real estate might have remained near the base line because short-lived crises did not disrupt their supply. Their demand was also flexible.

When Abdul Malik amassed his forces around Mecca to defeat Abdullah bin Zubayr and he instigated the residents of Mecca to abandon ibn Zubayr, he dumped the food in the camp he had established for Meccan refugees. Tabari reports that there was an ample supply of biscuits, barley meal and flour. A party of three could easily satisfy its hunger for one dirham. 39 That was ebb. The crest was when the Kharijis of Shayban were holed in Mosul by the forces of Marwan II. One loaf of bread sold for one dirham in Mosul. A few weeks later, food got so short that it disappeared from the market. No money could buy any food. 40 One dirham for a loaf of bread was extremely high price. Once Hisham wrote to his governor in Iraq, Khalid bin Abdullah al Qasri not to allow any crop of Iraq to be sold in the open market until the price of one loaf reached one dirham. 41 One dirham a loaf had stirred public discontent in Khorasan. That was during a local famine. 42 Food prices had varied effects in different parts of the country during the Rebellion of Commons. The Iraqi side had an abundant supply from all over Swad. On the other hand, the supply chain to Syria was blocked. Prices went up on the Syrian side to the extent that they did not have any meat. 43 The people of the Umayyad Caliphate expected a Qafīz (average 5 kg) of wheat should be four dirhams. That was the base price. 44 The base price of meat was definitely higher than that of cereals. Fish might be the most expensive meat. One piece was two dirhams. 45

The price of manual labour is a simple way to know the general wages in a country. The comparison of general wages with the price of staple food can give an idea of the regular well-being of average people. The labour contractors of Basrah used to pay a hired soldier ten dirhams daily. In turn, they supplied the soldier to the needy at thirty dirhams daily. 46 Similar figure comes from Kufa. The salary of a soldier ranged from three hundred dirhams to seven hundred dirhams per annum. 47 Salaries of the higher-ups in the military were definitely more. The regular salary of a military officer, for example, was two thousand dirhams per annum.48

Rate of skilled labourer depended upon his skills. A poet recited praise for Hisham bin Abdul Malik. Hisham paid him five hundred dirhams upfront and raised his salary for life.49

Real estate appreciated tremendously in Muslim neighborhoods. Mu’awiya bought a house in Mecca for four hundred thousand dirhams. 50 Price of an average home in Mecca was ten times lower in pre-Islamic times. 51

Agricultural property had comparable prices. Yazid III bought an agricultural estate for one hundred and eighty thousand dirhams in Syria. 52. A piece of agricultural land in Medina carried a hundred thousand dirhams. 53

Property development was expansive. A person received a rubbish dump outside Kufa as a fief from Yazid II. He had to spend one hundred and fifty thousand dirhams to clear it and make it cultivable. 54

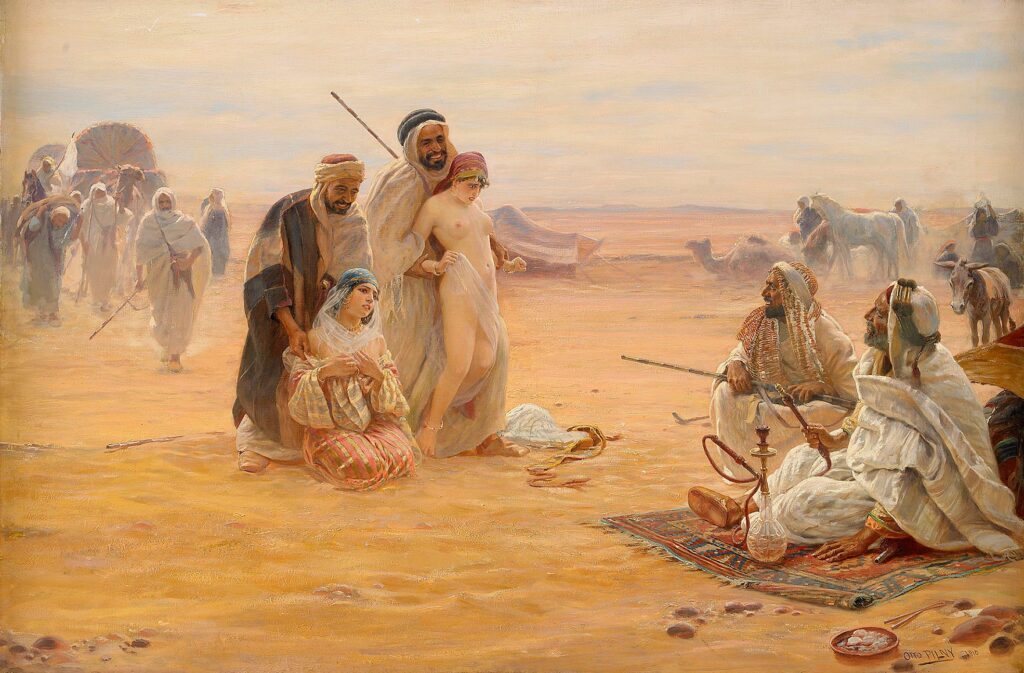

Slaves, both male and female, were an important part of the economy of the Umayyad Caliphate. It appears that the bulk of the labour force were slaves. The price of a slave, both male and female, depended upon his or her utility. A male slave who could write and knew arithmetic fetched a price of six hundred dirhams. 55. Abu Muslim, fetched a price of four hundred dirhams. Tabari says that his master sold him for below market price.56 Probably his master was not aware of his leadership qualities, which his Abbasid buyers had appreciated. Abu Muslim was illiterate. His new masters taught him after manumitting him.57

‘The Slave Market’.58

Blood wit was ten thousand dirhams.62 Some people were not going to be pardoned whatever they offered. A rich prisoner of war offered five thousand pieces of Chinese silk worth one million dirhams for his life. They did not accept his offer.63 Revenge was of utmost importance here. Sometimes there was too much at stake and the killer had to pay much more than the usual blood wit. Ahnaf bin Qays offered a hundred thousand dirhams for Azd’s slain young man. It was ten times higher than the usual blood money. 64 Basrah was boiling with tribal factionalism and if Ahnaf had not offered it, more bloodshed was imminent.

A good horse was an Arab’s weakness. The price of a male warrior horse was seven hundred dirhams.65 Good breeding mares fetched much higher prices. It could be up to four thousand dirhams.66

Good quality military ware had its own price. The best quality coat of mail was one thousand dinars .67

The price of luxury items can never be generic. Beauty lies in the eyes of the beholder. A big ruby was sold in Iraq for seven hundred and thirty thousand dirhams.68

Inflation was inflammatory

Like all times, the masses of the Umayyad Caliphate tolerated inflation poorly. It is particularly true for price hikes in food over a short period of time. Whenever food prices went up, the blame went to no one else but the ruler. Giving Qutayba bin Muslim a charge sheet before his execution, his killer Wakī’ blames him for being instrumental in the inflated prices of the goods. 69

Such blame to a ruler could go to any extent. Rulers were afraid of such accusations. When Hisham artificially increased the price of food in Iraq to sell his produce at a high price, people did not know who was behind the move. They blamed governor Khalid bin Abdullah al Qasri for the situation. Khalid felt so cornered that he did not mind disclosing to the people that it was Hisham rather than he. 70 Khalid knew that such behavior could cost him his life.

Rulers had their own coping mechanisms to deal with the blame of inflation. One argument floated by the rulers was that inflation was everywhere internationally. When Junayd faced the wrath of the Khorasani masses in the wake of rising food prices in the back drop of famine, he aptly announced that prices of food in Khorasan were the same as in India.71 Another way was to explain things in religious metaphors. During the same famine, Junayd exclaimed, “Merv used to be secure and tranquil, its provision coming to it abundantly from every place, but it became ungrateful for the blessing of Allah. [Quran 16:112].” 72

Currency

Both Dinars and Dirhams continued to circulate. Not all business transactions used either of the two. Barter trade was common. Slaves, both male and female, had become a currency in their own right. People used to pay by slaves. The recipient of the slaves could use them towards his own payments. Once Governor Khalid bin Abdullah al Qasri received one thousand slave youths and one thousand slave girls, in addition to cash. 73

Taxes and their collection

There were definitely changes in the Umayyad Caliphate in the tax law of the country, and the way they were collected as compared to the Rashidun Caliphate. There were also changes in the total revenues collected by the government and the way they were spent. Details are lost in history, only clues have survived.74

The most well-documented change was the drastic reduction in the revenues of jiziya tax. The rapid Islamization of the country hurt the government exchequer badly. A case study of the population of Najrāniyyah makes the point clear. Najraniyyah was a medium-sized town in Iraq, originally populated with forty thousand. The Christians of Najarn had founded this city after the Umar bin Khattab government expelled them from Arabia. 75 The Yazid bin Mu’awiya government had to reduce the tax burden on the Christian inhabitants of Najraniyyah because their number had decreased as a result of conversion and deaths. 76, 77 Initially, the Rashidun Caliphate imposed jizya per head after a census of each community. The chief of each non-Muslim community was responsible for collecting jizya from the member household and then delivering a figure calculated at the time of the original census to the government. Here, the request came from the community and the Yazid bin Mu’awiya government reduced the total jizya tax responsibility of Najraniyah without a new census. Later on, the Christians of Najraniyyah sided with the Rebellion of Commons and the Hajjaj government was unhappy about it. Hajjaj bin Yousuf repealed the reduction and reinstated the original jizya amount that was assessed by the Rashidun Caliphate. To punish the Christians of Narjraniyah further, Hajjaj prescribed a better quality of the goods that they used to pay the taxes. 78 The Christians of Najraniyah were one of those who took advantage of the reformist mood of the Umar bin Abdul Aziz government. In their complaint, the Christians of Najaraniyah pleaded to Umar bin Abdul Aziz that Hajjaj had treated them harshly and certain Arab raiders had also devastated them. In addition, their number had decreased further by conversion. Umar bin Abdul Aziz ordered a fresh census to verify the facts. The new census established that the number of Christians in Najaraniyyah had decreased by 90% from the original forty thousand at the time of its inception three-quarters of a century ago. Umar bin Abdul Aziz retained the original rate of jizya tax but changed the method of its collection. He dumped the lump sum figure and extracted per head Jiziya instead.79 The case points out the average rate of conversion among Christian Arabs in Iraq. It also verifies that gradually the Ashraf and their non-Muslim counterparts were eliminated from the tax collection apparatus. Lastly, it establishes beyond doubt that the government revenues from jizya tax reduced drastically.

Another important income source of the government also contracted in the Umayyad Caliphate. This was the 20% of the booty collected during a war against non-Muslims. This source did not vanish altogether. Once, the Umayyad Caliphate military plundered Sicily and brought back idols of gold and silver studded with pearls to Mu’awiya bin Abu Sufyan. Mu’awiya sent them to Basrah to be carried to India and sold there with a view to getting a higher price. 80 However, this source did not provide as much as it did to the Rashidun Caliphate. The only time the Umayyad Caliphate received a substantial share of booty was during the Second Phase of Futuhul Buldan when it expanded its borders. It was during this phase when the people of Gorgan agreed to pay Yazid bin Muhallab five hundred thousand dirhams, clothes and one thousand slaves annually. 81 It was a short-lived time and could not compensate for the rest of the tenure of the Umayyad Caliphate, which did not see any border expansion but only border raids.

As traditional sources of revenue were drying up, the Umayyad Caliphate had to find new sources. The Umayyad Caliphate slowly brought those groups into the tax bracket who were exempt from any kind of tax in the Rashidun Caliphate. Yazid bin Mu’awiya government levied jizya tax on the Samaritan Jews in Syria. They were particularly concentrated in Jordan and Palestine. Yazid imposed the same rate of jizya that was for other non-Muslims in the province. 82 The Umar bin Khattab government had exempted Samaritans from the jizya tax in recognition of their spying services during Futuhul Buldan.

Mu’awiya bin Abu Sufyan had already imposed a zakat tax on the salary (‘aṭā’) of the soldiers, which was exempt from any tax in the Rashidun Caliphate.

Another new source of revenue was the collection of costly gifts from the population. Throughout the Umayyad Caliphate, tax collectors were under pressure to collect and pay exorbitant gifts to their immediate bosses. 83

There is almost a consensus among historians that there was no uniform taxation system in the country. 84 It is likely that all provinces had slightly different tax structures. It took into account the capacity of the people to pay. My words. The principle of taxation according to capacity to pay is lucid from details of the kharaj tax in Iraq. According to Baladhuri the tax (ṭasq) rate on land was different depending upon the distance of the land from the market (māwardi) and distance from the drinking places in the river (furaḍ)85 It appears that the rate of zakat, the income tax on Muslims, was pretty fixed and it was 2.5% per year.

Sources tend to give figures of taxes in monetary units. However, people were free to pay in kind if they wished. Those who preferred to pay in kind started feeling disadvantaged. The government expected from them the same amount of kind each year, though the prices fluctuated. Umar bin Abdul Aziz’s reforms gave them relief. It fixed their tax amount in terms of monetary units and gave them a choice to pay an equivalent amount in kind. The people of Jazira who used to pay with oil, vinegar and food were beneficiaries of this policy. The policy applied to the jizya tax only. They still had to pay their kharaj tax in terms of a fixed amount of kind because it was a certain percentage of their crop. 86

It is almost impossible to know the true volume of revenue from different provinces in the Umayyad Caliphate. The changes in the tax structures and collection apparatuses make it difficult to compare available tax figures with those of the Rashidun Caliphate. Egypt was the largest tax-generating province of the Rashidun Caliphate. Its tax revenue had decreased to thirty million Dirhams during Mu’awiya bin Abu Sufyan’s tenure.87 The tax revenue of Swad was one hundred and twenty million at that time. 88 Basrah had become the largest province in terms of tax generation during Mu’awiya bin Abu Sufyan’s tenure. Tax collection from Basrah and its dependent territories had reached six hundred and fifty-five million dirhams annually. 89 Relatively barren provinces remained far behind. The combined revenue of Yamama and Bahrain was only fifteen million dirhams90 The tax revenue of the district of Homs, which was part of Syria province rested at three and a half million dirhams.91

The decrease in tax revenues of Swad during the later period of the Umayyad Caliphate is noticed by almost all sources. Baladhuri reports a sixty percent drop in the revenue of Swad during Abdul Malik’s tenure as compared to that of Umar bin Khattab. 92

All provinces did not send their share of revenue to the central government equally. It appears, for example, that Egypt sent very little. Ya’qubi reports that Egypt used to send very little to Mu’awiya bin Abu Sufyan during the governorship of Amr bin As. Even after Amr’s death, Egypt did not send much but instead spent funds on the military. 93 Tabari presents a similar picture. He tells us that when friction developed between the two brothers, Abdul Malik bin Marwan demanded revenue from Egypt from Abdul Aziz bin Marwan. Abdul Aziz bin Marwan did not pay anything but simply sent a message to Abdul Malik that the latter was making his life unpleasant in his old age. 94 It means Egypt had not paid anything to the center during the whole of Abdul Malik’s tenure and was not willing to pay. The situation probably remained unchanged in later times. We hear a lot of hue and cry about the revenues from Iraq and its dependencies, their collection, their payment to the Caliph etc. but we never hear of any dispute between the center and Egypt regarding revenues. The relatively docile role of Egypt in the political turmoil of the Umayyad Caliphate also strengthens the impression. The center had very little tax demand in Egypt, so the Egyptian people and the governor had no reason to be anxious who would govern the center.

A clash of interest between the taxpayers and the government was at the heart of many political clashes during the Umayyad Caliphate. Non-Muslims used to pay two taxes. Jizya was a tax levied on each non-Muslim household. It was in return for the protection of life, property, religion and customs of the non-Muslim provided by the state. The other tax was kharaj which was actually an income tax on the agricultural produce. Baladhuri mentions both of them clearly when he describes how the Yazid bin Mu’awiya government brought the Samaritan Jews of Palestine under the tax umbrella. Yazid assessed five dinars per head as jizya and the kharaj on their lands was extra.95

Kharaj was assessed on the land rather than on the household. Its rate was much higher than that of zakat which was a similar tax on Muslims. 96 The Umayyad Caliphate was of the opinion that the assessment of kharaj was attached to a particular piece of land. These were the lands which non-Muslims kept in their ownership at the time of Futuhul Buldan or the state nationalized them. The revenue department of the Umayyad Caliphate believed that the owner of those lands should continue to pay kharaj even if he converted to Islam or sold it to a Muslim. On the other hand, the Mawlas strongly believed that kharaj was imposed on the lands only because their owners refused to convert to Islam. If any of them converted, his land should be assessed for zakat. Certain opposition elements, particularly Muslims with a religious bend, agreed with the Mawlas. 97 The matter did not settle amicably. Mawlas constantly found that the tilling of land was not profitable under the burden of Kharaj. They abandoned their agricultural lands to seek alternate jobs in towns. The government pushed them back to grow food.

Islamic coin mentioning Jiziya.98

Rampant corruption

Yazid bin Muhallab snatched a big booty during his campaign against Gorgan. According to the law of the country, he should have documented the value of every article in a register with the sum total at the end. He should have then sent a copy of that register to the central government along with twenty percent of that sum. Instead, he promised to Caliph Sulayman bin Abdul Malik that he would bring the fifth of the booty to Sulayman by himself in the future. By gaining a bit of time, Yazid bin Muhallab started open consultations with his subordinate commanders about how much he should declare. Many different opinions emerged ranging from declaring zero to somewhere in between its actual value. Yazid ultimately declared four million dirhams. The actual booty was worth six million and everybody present knew that. 99 This is a classic case of economic corruption. Declaring a lesser amount left more for the commanders. It is worth noting that Yazid executed corruption after an open discussion about how much of it could be reasonably hidden. ‘Transparent corruption’ is possible in only one scenario. That is the scenario of everybody being totally corrupt. The executor of corruption can talk about his plans with anybody without the fear of repercussion and with confidence that the listener would become part of the scheme and would defend the corruption honestly. The Umayyad Caliphate was a nucleus of economic corruption.

Bribery was the main tool to avoid the consequences of corruption. The Umayyad Caliphate was a society of gifts. Mostly bribery was hidden in the form of a gift. Muhallab bin Abu Safrah paid Barā’ Bin Qabīṣah, the inspector sent by Hajjaj to find out if Muhallab was actually fighting, ten thousand Dirhams, fine garments and a mount. Bara inspected one battle and confirmed to Hajjaj that the fighting was fierce and the Kharijis were stubborn fighters. 100

Many times when an officer was charged with corruption or stealing government money, he simply admitted to it and asked the government to convert the amount into a debt which he would pay back. 101

All and sundry made money by use of their official position. The people of the Umayyad Caliphate had a saying, “It is good to be in authority even over stones.” The background of the saying is said to be the renovation of the grand mosque of Kufa. Ziyad bin Abihi/Abu Sufyan ordered that pebbles be strewn in the courtyard of the mosque. The overseers of the work used to oppress those who gathered the pebbles saying, “Bring us only this kind which we show you,” choosing special samples, and asking for similar ones. By such means, they enriched themselves. 102 Enriching self by abusing power was so common that it was almost normal. When Governor Ummayah of Khorasan appointed Bukayr as district governor of Tukharistan, Bukayr spent a lot of money in preparation for departure. He actually borrowed a big amount in the hope that he would return it after earning it from his job. 103

Arabs did not spare any chance of forgery. Once Mu’awiya bin Abu Sufyan ordered Ziyad bin Abihi/Abu Sufyan to pay back the debt of ‘Amr bin Zubayr bin ‘Awwām, which was one hundred thousand dirhams, through a letter to Ziyad. Amr opened the letter and changed the amount to two hundred thousand dirhams. When Ziyad presented his invoice to Mu’awiya, the latter disclaimed it. He then asked Amr to return the money and imprisoned Amr. His brother Abdullah bin Zubayr repaid the money on his behalf. That time Mu’awiya established the department of the seal, and he tied the letters, which had not been tied before. 104

Corruption was at a grass root level. Imitated coins were in circulation in Sistan in the late 8th century. 105

The existence of widespread corruption at all levels had not eliminated its sense of being a bad thing from the minds of people. People knew what amounts to corruption. When Yazid bin Muhallhab was governor of Iraq for caliph Sulayman, he prepared one thousand tables to feed his men at government cost. Sāliḥ, the finance secretary to Yazid bin Muhallab, appointed directly by Sulayman, seized them. Yazid had to pay the cost of the tables. Yazid also purchased many goods from the market for personal use and wrote checks from the treasury for their payments. Salih refused to clear the checks and the vendors demanded money from Yazid. Salih told Yazid gently that the provincial exchequer had cleared all the checks written by Yazid to pay salary to his soldiers in a timely fashion. The total amount of those checks was one hundred thousand dirhams. They were cleared because they were legitimate expenses. Salih would not clear any check for the governor’s personal expenses. 106

Managers at the highest levels were fully aware of rampant corruption and occasionally took measures to control it. Defending his decision to appoint a dihqan (people of Persian ethnicity) over financial matters, Governor Ubaydullah bin Ziyad said that whenever he appointed an Arab to the post of tax collector, the collection was insufficient. When he investigated and imposed fines on him or the leaders of his people or upon his clan, they got offended. If he appointed dihqans, he found them more punctilious in collecting tax, more trustworthy, and less demanding than Arabs. 107

It is no surprise that all government officials were super rich. Even those who only enjoyed the government office for a short period got something out of it. Abdullah bin Amir bin Kurays, Mu’awiya’s governor of Basrah, owned agricultural estates, orchards and palaces in many towns including Basrah, Mecca, and Taif. 108

Government control on measuring scales

The widespread Umayyad Caliphate continued to have many different measuring scales. It is evident from a variety of names mentioned in historical sources for measuring the same attribute. The measurement of distance, for example, was in miles as well as farsakhs. 109 The government did not strive to introduce a common scale for the whole country. Instead, it tolerated the regional variance of the scales very well. Archaeological finds suggest that what the government was emphasizing was the standardization of measures, particularly after the Second Arab Civil War.

A piece of bronze used to weigh equal to six mithqāl (25.5 grams) is preserved in the British Museum. Its inscription is clear that it was issued on the authority of Hajjaj bin Yousuf and emphasizes honesty in measuring. 110 A weight of one Raṭl (175.5 gram) is preserved in the National Museum of Damascus. It was issued on the authority of Caliph Walid bin Abdul Malik. 111 A weighing measure of 4.29 grams, made up of glass, is preserved in the British Museum. It was issued on the authority of Abdul Aziz bin Marwan. 112 There are many others in private collections. All point to one fact. Regulating weights was a provincial matter. Weights bore engraved Islamic formulas in line with coins. All surviving weights belong to the post-reform period. Abdul Malik is widely renowned for carrying out reforms in weight measures.

Bronze weight mentioning Hajjaj bin Yousuf.113

Environment – stepmother of economy

When Muhammad bin Qasim captured Sind, he sent thousands of buffaloes to Hajjaj as booty. Hajjaj apparently did not know what to do with them. He abandoned many of them in the wilderness of Kaskar and around River Euphrates. He also sent at least four thousand buffaloes to Caliph Walid. Even Walid didn’t know what to do with them. He released them around Massisah. Lions used to threaten the travellers on the Massisah – Antakya road. The buffaloes soon cleared the area of all lions. 115 This is a classic example of how we humans have ravaged our mother – the planet Earth. People and the rulers of the Umayyad Caliphate had nothing to do with environmental protection. Our modern research is establishing that people who are more connected to nature, do more to protect it.116 None of the rulers of the Umayyad Caliphate were connected to nature. The state forces captured a species from a unique biosphere. There was no reason to transport it to another biosphere. People in other biospheres did not know how to utilize it. Yet, they did not want to dishearten the forces by simply telling them upfront that the gift was unwanted. They needed an excuse to discard the animals. They created a fancy argument that releasing the animal in a jungle infested with lions was a public good. The weakness of the argument is obvious. The Massisah – Antakya road was not the only route in the country that passed through the wilderness. Lion encounters were common on the highways all over the country and the travellers knew how to tackle the issue. 117 The buffaloes did not have any natural enemy. They doubled in number in a few decades. By that time people had learned how to use them. They started stealing them from the wilderness with the aim of domestication. The practice got so out of control that after the Umayyad Caliphate was over, Caliph Manṣūr had to issue a decree that the animals in the wild were government property and people should return the wild buffaloes to the wilderness. 118

Generally speaking, the people of the Umayyad Caliphate considered animals and nature an evil which hindered the development of human society. No historical source for that time could resist boasting about how animals disappeared from the landscape after the founding of Kairouan. 119 “The site being thicket covered with tamarisk and other trees, nobody could attempt because of the beasts, snakes and deadly scorpions. This ‘Uqbah was a righteous man whose prayer was answered. He prayed to the Lord, who made scorpions disappear. Even beasts had to carry their young and run away”, are the words of Baladhuri. 120

Arthropods were the most hated creatures. Once the amil of Nisibayn wrote to Mu’awiya bin Abu Sufyan that some Muslims had fallen victim to scorpions. Mu’awiya ordered him to demand the inhabitants of each quarter to bring a fixed number of scorpions each evening and to kill them. The amil did so. 121 Biologists are pointing out that each species has a natural fear for certain other species. A baby monkey is afraid of snakes even if he has never seen one before in his life. It is quite possible that humans have fear of arthropods in their DNA.

Private property rights

Prophet Muhammad had granted to Bilāl bin Ḥārith of Muzaynah a mountainous piece of land in Hejaz as a fief. His descendants sold it to Umar bin Abdul Aziz. Umar explored and found a mineral mine in the land. The descendants of Bilal disputed with Umar that they had sold the tillable land, not its other resources. Umar returned the profit of other resources to the sellers.122 It is a typical example of selling a right rather than selling a whole article.

Labour market and slavery

Labour market totally consisted of slaves. Constant border raids were the main source of slave labour. The acquisition of slaves was a part of any such agreement after a successful raid. Capturing slaves from their country was the responsibility of the defeated. Masqala bin Hubayra al Shaybani, for example, defeated the people of Tabaristan. He made peace with the inhabitants against payment of five hundred thousand dirhams, with a weight of five (mithqals) and hundred ṭaylasāns and three hundred heads of slaves. 123 It appears that the majority of slaves in the later part of the Umayyad Caliphate were of Turk origin. Sources mention Turk slaves more frequently than of any other ethnicity. 124

If any free labourers were available, they were treated like slaves. They were underpaid and forced to work on those wages. Once Hajjaj dug Nahr Ṣin of Kaskar. He ordered the workers to be chained together so that none of them might run away as deserters. 125

Arabs into trades

Arabs had started settling in the conquered lands as soldiers and government officers. As time passed, many of them abandoned military service and adopted trades. Some started agricultural farming. A certain Abu Ṣāliḥ owned a vineyard in Rayy, near the gate of the town. 126 Even the Caliphs were involved in big-time agriculture. They could not manage their cultivation personally due to time constraints. They hired business managers. Ḥassān al Nabaṭi was the manager of Hisham bin Abdul Malik’s extensive estates in Syria. 127 Arabs were not alien to trading and manufacturing. Actually, some of them made fortunes in such businesses. 128 They had gone into the service sector as well. A certain Umar had established a public bath (hammām) near Kufa. The business became so popular that the place itself became known as Hammam Umar. 129 Definitely each Arab was not fortunate enough to establish a dashing business. Some, like Balta’ al Sa’di of the Tamim tribe, were petty vendors. Balta used to sell clarified butter in Basrah at the caravan’s station.130

Hierarchy of trades

Abusing the people of Abdul Qays, Qutayba bin Muslim says, “You have taken up the pollination of palm trees in exchange for horses’ reins.” He further abuses Azd that ‘you have taken ship’s cables in exchange for the reins of fleet stallions’. He blames ‘it is innovation in Islam’. 131 Arab society had a conceptual hierarchy of trades. The hierarchy had no relation with the money a trade could generate. Trades and professions that helped in establishing bossiness over others found higher places in the hierarchy of trades. In the case of Qutayba, he considered a soldier superior to a trader or a farmer. However, we know traders and farmers could sometimes earn more than a soldier. The more authority, the higher the trade. Bukayr was the lieutenant governor of Khorasan. Caliph Abdul Malik bin Marwan dismissed him in 693 CE and appointed Umayyah bin Abdullah in his stead. Umayyah knew that Bukayr must have a sore heart. He offered him to head his security forces. Bukayr’s well-wishers advised him to accept the offer but Bukayr rejected it. Bukayr’s argument was, “Yesterday I was governor of Khorasan, with Javelins (ḥarbah) carried before me. Shall I now become head of the security force and carry a javelin myself?” 132

Manual jobs at the bottom of the hierarchy

Arabs looked down upon manual jobs. Probably it was not because the manual worker earned little. It was because manual work was the least authoritative. Manual job had become a kind of abusive word. Using the worst abusive words available in his vocabulary against a dissident, Hajjaj calls him ‘the protector of the son of weaver’. 133 Husayn bin Ali is also reported to have used manual work as a taunt. He called his opponent, Shamir bin Dhi al-Jawshan, ‘son of a goat herderess’ before the start of a fight at Karbala. 134 The trend continued throughout the life of the Umayyad Caliphate. Waki’ the upriser against Qutayba bin Muslim calls a person a blacksmith just because he had lied to him. 135

Arabs shunned from manual work for obvious reasons. One had to hire non-Arabs for such jobs. Once a plague spread in Basrah and many died. One of the dead was the mother of Governor Abdullah. Abdullah could not find anybody to carry her body to the burial. He hired four non-Arabs who carried her to the grave. And he was governor at that time! 136

Government job best profession

The way people strived to be in the good books of a caliph or governor, and the way they ached to be a government servant, it is clear beyond doubt that government job was the most sought-after profession. It was not only authoritative but also the best paying. The annual income of Governor Khalid bin Abdullah of Iraq was a solid thirteen million dirhams.137 Actually many government officers, including the caliph and his family members, were enrolled in the military register. It affirmed them an additional status of a soldier, which was in itself a higher job in the hierarchy of trades. The caliph and his close family members could easily avoid risking their lives on the battlefield by either not drawing their soldier’s salary, sending a proxy to the battle by giving him their salary and one buck extra as a symbol, or by getting appointment of noncombatant military posts like diwan guards (fī’wāni al dīwān ). 138

Beggars and begging

Do beggars work? If we define work as ‘doing something to earn a wage’, yes they do! They fulfill an important demand of society – an urge to proudly give away, an urge to express sympathy. Begging has nothing to do with poverty. It flourishes in a society in which public display of charity is appreciated. The Umayyad Caliphate was as self-sufficient in beggars as the Rashidun Caliphate. On his way back to Damascus from pilgrimage in 716 CE, Sulayman stayed in Jerusalem. There lepers circled his camp, ringing their bells so that they prevented him from sleeping. Sulayman got so annoyed that he banished them to an isolated village. Probably they used to provide begging services to the Christian religious tourists. Sulyaman might be mindful of Christian uproar. Umar bin Abdul Aziz advised Sulayman to proclaim that the reason behind banishing them to an isolated village was public safety. The act prevented them from being mixed up with healthy people. 139

Population census

The Umayyad Caliphate, like its predecessor, the Rashidun Caliphate, emphasized the population census. The census of a province was a once over a time event but probably the census of individual communities was an ongoing practice. A document in the Coptic language is preserved in the British Museum. (accession number: BM 1079). The text is an affidavit on oath from the village headman that he has counted all his men honestly. It is probably part of the census in Egypt. The papyrus is undated but it mentions the name ‘Amr. Crum is confident that he is no other but Amr bin As and considers this papyrus from at least before the death of Amr bin As i.e. 663 CE. The affidavit also sheds light on the government and Christian relationships. They were being governed by intermediately village headmen before the Second Arab Civil War. 140

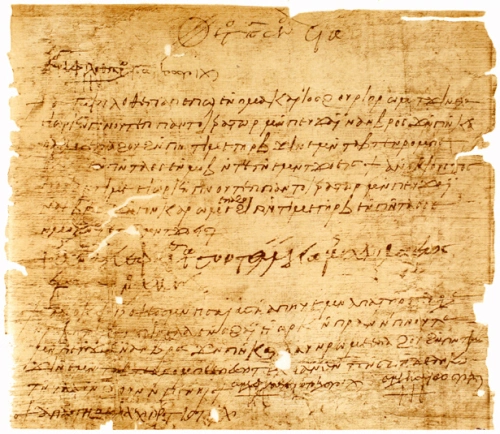

A census document from the Umayyad period.141

Size of cities

Regular censuses helped in tracing the growth or decline of the population over time. The big cities of the Umayyad Caliphate were ever-growing. When Yazid bin Mu’awiya attained caliphate, the total number of fighting men in the register of Basrah was seventy thousand. At the time of Yazid’s death, the number increased to eighty thousand. The number of dependents in the register was ninety thousand at the ascension of Yazid. By the time of his death, this number had swelled to one hundred and forty thousand. 142 The disproportional growth of dependents probably reflects increase in the number of Mawlas.

Internal immigration

Internal immigration, which had started during the Rashidun Caliphate, continued to change the population profile in the Umayyad Caliphate. Economic immigration was towards the land of opportunities from areas of stagnant growth. One person Khashram bin Mālik of the Asad tribe, for example, moved out of Kufa and settled in Jibal near the end of the Umayyad Caliphate. His descendants continued to live in the area and were called emigrants from Kufa at the time of Baladhuri’s writing. 143 Not only Arabs, but non-Arabs also immigrated for economic reasons. Some Hamra’ moved out of Basrah and settled in the district of Isfahan during Hajjaj’s tenure. 144 Generally economic immigrants are ambitious and hard-working. They perform better than the locals do. Most of the immigrants got wealthy in their new abode and their descendants enjoyed the fruits. 145

Involuntary immigration was also present. It was forced by the government for political reasons and carried government-generated economic incentives. Maslamah bin Abdul Malik settled twenty-four thousand Syrians in Bab in Armenia and assigned them a stipend. Since then, the descendants of the group thrived on stipends and didn’t settle for anything less. 146 Bab was a border area and the presence of a loyal Arab population was a precondition for government success there. Similarly, the Umayyads faced resistance from the local Arab tribes after they got control of Jazira after the Second Arab Civil War. Muhammad bin Marwan, governor of Mosul, transferred the tribesmen of the Azd and Rabi’a from Basrah to Mosul. 147 On the same lines, Mu’awiya had to inhabit the Mediterranean islands that he had captured. His government developed settlements of Muslims in many of them, for example, Rhodes. Rhodes was a thicket at that time but it was a fertile land capable of producing olives, grapes and fruits at the time of Baladhuri’s writing. 148, 149

Natural catastrophes

An abundance of natural disasters and catastrophes remained a salient feature throughout the Umayyad Caliphate. There was hardly any year which was devoid of such news. The plague was almost endemic. 150 Here is a report of plague in Basrah area, “In 131 there was a plague in Basrah. The plague began in Jumada II of 131. Many died from it. It continued in Rajab and got worse in Sha’ban. It reached its peak of its virulence during Ramadan and Shawwal. Then it decreased in severity, and returned to the way it began, until the end of the year.” 151, 152 Earthquakes created their own havoc. According to Ya’qubi, the Syrian earthquake of 712 CE destroyed everything. The tremors lasted for forty days. 153

Wildfires had their own role. In 726 CE, a wild fire at Dābiq gutted whole grazing land along with the animals and humans.154, 155 Droughts were unavoidable. When a drought came, it affected the whole region rather than some districts. Ifriqiya observed such a drought in 711 CE. 156

Historical sources note natural disasters loyally, specifically mentioning the name of the caliph during whose tenure it happened. Their implied reference is clear. The general public believed that all natural disasters were from the Supernatural Being and were manifestations of His wrath for something wrong on the earth. It was either the sinful behavior of the masses or of rulers.

The rulers, on their end, tried to console people through religious rituals as well as secular measures. During the Ifriqyian drought mentioned above, Musa bin Nusayr went out and prayed for the rain (istisqā’). He also rationed water, making sure that everybody had at least drinking water if not for other needs. 157

Uncertainty of life / low life expectancy

The life expectancy during the Umayyad Caliphate was not high. If a man crossed fifty, he was lucky.158 Bloody wars, uncontrollable diseases, natural disasters, and infighting all had their own toll.

Start of a week

A typical week started on a Friday. That is the reason the Umayyad Caliphate had to pay Byzantine Rome one thousand dinars each Friday according to the peace treaty of 689 CE between the two. 159

Conclusion

The economy of the Umayyad Caliphate was diverse, robust and progressive. The government had taken a more active role in regulating the economy as compared to the Rashidun Caliphate.

- See above.

- See above.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 450, 454

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 456

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 232

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 433

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 38.

- M. M. Diakonov, “Concerning an Early Inscription”, Epigrafika Vostoka Volume 1 (1947): 5 – 8, figure on 6,7. AND B. Gruendler, The Development of the Arabic Scripts: From the Nabatean Era to the First Islamic Century According To the Dated Texts, 1993, Harvard Semitic Series No 43, Scholars Press Atlanta (GA), pate 154.

- Current location: Georgian National Museum, Tbilisi (W/kl/5).

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 180

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 181

- Florence E. Day, “The Tiraz of Silk of Marwan” in Archaeologica Orientalia in Memoriam Ernst Herzfeld, ed. G. C. Miles, (Locust Valley (NY): J. J. Augustin, 1952), p 39 – 61, plate VI. AND B. Gruendler, The Development of the Arabic Scripts: From the Nabatean Era to the First Islamic Century According to the Dated Texts, 1993, Harvard Semitic Series No. 43, Scholars press: Atlanta (GA), pp 16 – 17. Florence Day dates it to the time of caliph Marwan bin Hakam (683 -685 CE). Some scholars insist that it could have belonged to Marwan II (744 – 750 CE). They extend the period from 683 to 750 CE.

- M. A. A. Marzouk, The Turban of Samuel Ibn Musa: the Earliest Dated Islamic Textile”, Bulletin of the Faculty of Arts (University of Cairo), Volume XVI, Part II (1954): 143 – 151, plate facing p 150.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXI, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Michael Fishbein (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 102

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Martin Hinds (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 178.

- When a resident of Medina went to Mecca in 710 CE with the intention to perform ‘Umrah, he rented a house from a political dissident for a short term. The local governor was alerted and summoned him to explain his conduct. He explained that he himself was obedient to the government and he chose that house for his short-term rental as a recurring client. The governor warned him that renting a house from a disobedient was not a crime but it was something the government disliked. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Martin Hinds (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 178.)

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXIV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. David Stephan Powers (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 175, 176.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 454

- For an example of naft and its use see: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Khalid Yahya Blankinship (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 154.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 259, 260

- Adhanah of Arabic sources is Adana in modern south eastern Turkiye.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Michael G. Morony (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1987), 223

- Y. Ragib, “Les Plus Anciens Papyrus Arabes”, Annales Islamologiques, 1996, Volume 30, Issue 1, P 14. Fig 3.

- See for example, M. Tillier and N. Vanthieghem, “Recording Debts in Sufyānid Fusṭāt.: A Reexamination of the Procedures and Calendar in use in the First/Seventh Century”, in J. Tolan (ed), Geneses: A Comparative Study of the Historiographies of the Rise of Christianity, Rabbinic Judaism and Islam, 2019, Routledge: London, pp 148 – 188. And Y. Ragib, ‘Une Ere Inconnue D’Egupte Musulmane: L’ere De La Juridiction Des Croyants”, Annales Islamologiques, 2007, volume 41, pp 187 – 207. And M. Shaddel, “The Year According to the Reckoning of the Believers”: Papyrus Louvre Inv. J. David-Weill 20 And the Origins of the Hijri. Era”, Der Islam, 2018, volume 95, Issue 2, pp 291 – 311

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Martin Hinds (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 67.

- Actually, there is strong evidence that the government transferred the debt of a dead person to his property. The problem was that the heirs of the dead could hurriedly distribute the property among themselves, leaving the creditor unpaid. A papyrus kept in the Egyptian National Library, Cairo, arises from a similar situation. A peasant died and his heirs took his belongings. His creditor complained to the governor. This letter is from the provincial governor to the district manager written in January of 710 CE ordering the district manager to look into the facts of the complaint. If proof became available, the district manager had to reclaim the property of the dead from his heirs and pay the debt out of it. (A. Grohmann, Arabic Papyri in the Egyptian Library, Volume III, (administrative texts), 1938, Egyptian Library Press, Cairo, pp 30 – 33. A similar letter is on pp 33 – 35.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 488

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Everett K. Rowson (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 166.

- A. Hanafi, “An Early Arabic Business Letter”, in P. M. Sipesteijn, L. Sundelin, S. T. Towar & A. Zomeno (ed), From Al-Andalus To Khurasan: Documents From Medieval Muslim World, 2007, Brill: Leiden & Boston, pp 153 – 161

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. John Alden Williams (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1985), 42.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXIV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. David Stephan Powers (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989),12.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Everett K. Rowson (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 57.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Martin Hinds (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 27, 28

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 1001.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Martin Hinds (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 144.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Martin Hinds (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 144.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 228

- Baghras in Arabic sources is the ruined Bakras Castle in modern southeastern Turkey.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXI, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Michael Fishbein (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 209.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. John Alden Williams (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1985), 60.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Khalid Yahya Blankinship (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 186, 187.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Khalid Yahya Blankinship (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989),100, 101.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Martin Hinds (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990),26.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXIV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. David Stephan Powers (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 22.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Khalid Yahya Blankinship (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 153.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXI, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Michael Fishbein (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 174.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXI, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Michael Fishbein (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 191.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXVI, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Carole Hillenbrand (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989),74

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXVI, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Carole Hillenbrand (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 80.

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 38. Here 40,000 dinars are converted to dirhams.

- See above.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXVI, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Carole Hillenbrand (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 216. 18,000 dinars are converted into dirhams

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXVI, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Carole Hillenbrand (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 5. Ten thousand Dinars are converted into dirhams.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 442

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Khalid Yahya Blankinship (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 6. Sixty dinars are converted into dirhams

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXVI, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Carole Hillenbrand (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 66, 67.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXVI, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Carole Hillenbrand (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 66, 67.

- Current location: private collection. Oil on canvas. Otto Pilny, 2010.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXIV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. David Stephan Powers (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 196. Four thousand dinars are converted into dirhams

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXI, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Michael Fishbein (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 200).

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 974. Ten thousand dinars are converted into dirhams.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXVI, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Carole Hillenbrand (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 218.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Martin Hinds (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990),136, 137.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XX, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989),42.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. John Alden Williams (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1985), 63.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Martin Hinds (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 229.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXVI, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Carole Hillenbrand (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 264, 265

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXVI, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Carole Hillenbrand (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 82. Seventy-three thousand dinars are converted into dirhams

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXIV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. David Stephan Powers (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 22.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Khalid Yahya Blankinship (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 186, 187

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Khalid Yahya Blankinship (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 100, 101.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Khalid Yahya Blankinship (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 100, 101.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Khalid Yahya Blankinship (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 178.

- For a general overview of taxation see: Lokkegaard, Islamic taxation in the classical period, Copenhagen, 1950.

- See above

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 104

- Najraniyyah is an unknown locality. There is a village by the name of Nijran in southern Syria. Some scholars claim that it was Najraniyyah. However, it is far from Iraq in Arabic sources.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 104. They used to pay in kind in the form of clothes

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 104

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 375

- Khalifa Ibn Khayyat, Khalifa ibn Khayyat’s History on the Umayyad Dynasty (660 – 750), ed. and trans. Carl Wurtzel, (Liverpool, Liverpool University Press, 2015), P 189, 190, Year 97.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 244.

- See an example: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Michael G. Morony (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1987), 68, 69. The gifts were exorbitant. One gift could amount to up to one million dirhams. See: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. John Alden Williams (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1985), 31.

- See: D. C. Dennett, Conversion and the poll tax.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 429.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 278

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 914.

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 912

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 912

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 912

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 914.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 428. See also: Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 1001. AND Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXIV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. David Stephan Powers (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 163.

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 913

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Martin Hinds (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 111.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 244

- D. C. Dennett, Conversion and the poll tax. AND G. R. Hawting, The First Dynasty of Islam, (London: Routledge, 2000), 76 – 81

- For the opposition of religious element to such governmental policies see: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Martin Hinds (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 67.