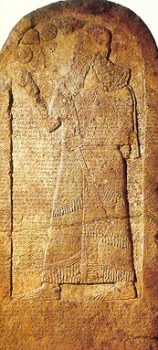

Kurkh Stela1

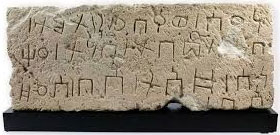

A Hasaean Inscription3

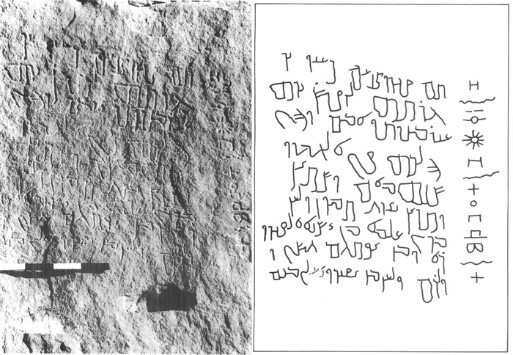

Rukash Inscription 7

By mapping the geographic distribution of Arabic language inscriptions and abodes of Arabic poets of that time, one can conclude that by the beginning of the 6th-century different dialects of Arabic were spoken all over Arabian Peninsula and Sinai.9 It does not mean that this was the only language spoken in Arabia. Aramaic, Syriac, South Arabian and Greek all had their share, mainly in the north and south.10 The overwhelming majority of the population in the peninsula in the 5th century CE was Arabic speaking and identified themselves as Arab.11 They were called Saracens (born to Sara, Sarah, Saʾrah ساءره) and Ishmaelites (descendants of Isma’il اسماعيل) by their neighbouring nations.12 Northern Arabs were fairer in complexion than the southern Arabs. That is the reason when the deputation of Najran came to Prophet Muhammad (Muḥammad Mohammad محمّد ) he asked ‘who these Indians are?’13, 14

Scholars are still debating what the term ‘Arab’ meant to Arabs living in Arabian Peninsula in the 6th century. One thing is definite. They did not have a notion of being a nation in the modern sense. Probably their self-identity as Arabs was through shared culture and language. The use of the term ‘Arab’ is relatively underrepresented in pre-Islamic poetry. It was rather used as a reference to the culture of the group rather than a political entity an individual would associate with. It means a group of people could be the best Arabs but an individual would still be a Quraysh (Quraish قريش) or a Bakri and not Arab. For example, Imru’ al-Qays (d. c. 540 CE), the chief of Kindah, while praising his father, does not claim that he was the best of Arabs but says he was the best of Ma’add. The term Arab began to be used in the works of Ḥassān bin Thābit, the Prophet’s ‘poet laureates’ and occurs more frequently in poetical texts of the Umayyad period to designate ‘the Arab nation.15 On the other hand, it does not mean that pre-Islamic Arabs were far distant from melting into a nation. Actually, there is evidence that settled Arabs had started associating themselves with the region they resided in.16 Scholars consider this kind of association the first step towards the development of national sentiments. A nascent nationalism might be present in Arab society by the time Prophet Muhammad started his mission.

Arab’s self-identity before Islam was tribal. It simply means individuals were identified by the tribe they belonged to. A tribe’s name was a kind of identity card for a person. Each and every individual needed to know his genealogy, the knowledge of his descent. And by proclaiming genealogy he earned a right to be part of one of the tribes. The tribe was a basic unit of social structure. Belonging to a tribe was a compulsion of life in areas where the state was less developed and the tribe was the only means of an individual’s protection.17

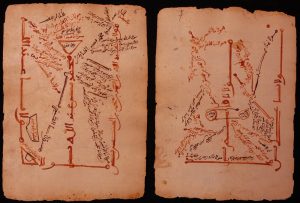

An ancient Arab Genealogy, preserved in Timbuktu18

Safaitic inscriptions, found all over North Arabia and dating from pre-Islamic times, often record a person’s genealogy going back to as many as fifteen generations. Hoyland believes that these inscriptions testify that kinship was not only real but also important.19 However, the kinship of all members of a tribe was not necessarily shared, even in situations where a tribe comprised of real descendants of one person. We know sometimes people not belonging to a tribe were added to it. Then they gained descent from the tribal ancestor in the name. For example, Prophet Muhammad adopted his slave Zayd bin Hārith as his son before his prophethood and from that date he was called Zayd bin Muhammad.20 It means a tribe could comprise of actual descendants of an ancestor, full members and those who attained ancestry in name, affiliated members. The principal social distinction within a tribe was between full members and affiliated members/dependents. There were many ways to become an affiliated member of a tribe. Individuals or groups escaping vengeance, impoverishment or in need of support for some other reason were sometimes admitted into a tribe as an affiliate member. Such Protégés were called jīrān (جيران). Similarly, sometimes an Arab was enslaved in war (‘abd عَبد). After being manumitted and adopted he could be incorporated into the tribe as a member if he wished to do so, though most preferred to remain in the tribe of their birth. Lastly, there were allies (ḥulafa حلفاء), individuals or groups spending a long time with a foreign tribe and ultimately developing a protective relationship with a native host tribe.21, 22 A tribe was not apt in taking affiliate members. An incidence narrated by Ṭabarī (an indispensable Islamic source active in the first quarter of the 10th century) exemplifies how damn difficult was it to attain membership in a respectable tribe. “When [the Iranian commander] Basak son of Mahbudh began work on [the fortress of] Mushaqqar [in east Arabia], he was told ‘these workmen will not remain in this place unless they are provided with womenfolk’ …. So he had whores brought for them from lower Iraq …. The workmen and the women married each other and begat children, and, they soon constituted the majority of the population of the city of Hajar. They spoke Arabic and called themselves after [the tribe of] ‘Abd al-Qays. When Islam came, they said to ‘Abd al-Qays: ‘you know well our numerical strength, our formidable equipment and weapons, and our great proficiency, so incorporate us among you and let us intermarry with you’. ‘Abd al-Qays responded: ‘no, remain as you are, as our dependent brethren’. But one ‘Abdi said; ‘people of ‘Abd al-Qays! Follow my advice and accept them, for the likes of these are highly desirable’. Another said; ‘Have you no shame? Are you telling us to receive a people whose origins and ancestry are as you know?’23

Membership of a tribe created certain rights for the individual. One such right was to be protected by the tribe. At the same time, membership generated liabilities, like the duty to protect other tribal members, and the responsibility to follow tribal traditions.24

There was no official chief of the tribe, let alone a hierarchy. Still, no social organization can work effectively without a leader and the pre-Islamic Arab tribe was no exemption. Tribes did have their informal leaders called shaykh (شيخ). A shaykh was only primus inter pares. There is not a single historic source recording a tribal gathering held for the sole purpose of selecting a tribal chief. He had to win his authority through his own efforts like heroism in war or contribution towards peace. Tribesmen started following a person in whom they saw qualities they perceived necessary for being a leader. Sometimes a leader acquired the position of any official character by being appointed to, or confirmed in, his office by a non-Bedouin power. Such non-Bedouin powers were neighbouring states like Sassanian Iran or Byzantine Rome.25

An Arab Shaykh26

Who now will help the indigent when they cry out?

And who will strain the tips of supple spears with blood?

Who will cast lots for the slaughter came when the morning wind cuts through the knotted ropes?

Who will come forward with blood monies and gather them?

And who will succour us when calamities befall? ?28

Pre-Islamic Arab tribes were both nomads and sedentary. Nomads (Bedouin, baddū, بدو) roamed around the countryside grazing their camel and sheep herds. The sedentary (al-mustaqraʾ المستقرأ) lived in fixed settlements as farmers, traders or perusing other economic activities.29, 30 Exact percentage of either Bedouin or sedentary Arabs in the total population is not known. Many regions of Arabia like Yemen, Ḥaḍramaut, Oman, Iraq and Syria (Bilād ash shām بلاد الشام), were almost completely settled.

A Sedentary Arab 31

Very few tribes, for example, Banu Ḥanīfa, were totally sedentary.34

The tribal organization of the society had originated from and was maintained by nomads. Harsh grazing conditions compelled Bedouins to split into small groups of fifteen to twenty tents. Simultaneously, security need compelled them to be within a few hours’ distances of each other to gather a group of up to about five hundred tents when needed. These natural needs of Bedouins organized them into the tribal system.35 Nomads were essential part of the society. They continuously interacted with the settled population. It was one of the primary reasons why the history of the Middle East differed from that of contemporary Europe, which did not have interaction between nomads and the settled.36 Those were, however, town dwellers who inculcated the sense of Arab solidarity in the Bedouins.37 And those were mainly town dwellers that ultimately embraced Islam and spread it enthusiastically.

A Bedouin Couple38

Bedouins still enjoy a nomadic lifestyle 39

Sharing food: present-day Bedouin’s murūʾah41

When you have prepared the meal, entreat to partake thereof a guest

I am not one to eat, like a churl, alone

Some traveller through the night, or protégé, for in truth

I fear the reproachful talk of me after I am gone.44

Look at verses of another pre-Islamic poet ‘Amr ibn Qami’ah:

Many’s the good companion, noble of ancestry, liberal, have I given

To drink before dawn a morning draught in a cup of wine bought dear…

And I tarried not, but sent my servant at once to seek

The best of my fat young she-camels with a large hump

And she strove to rise, though resisted to be led along, and I hamstrung her with my sharp-cutting Mashrafite sword.

And my fellow dallied long in luxury, waited upon, and later enjoyed a noble feast, to which all neighbours came.45

The judge of sticking to muru’ah was public opinion. It was so important to Arabs that, for example, Samaw’al bin ʾĀdiyā’ permitted a son of his to be killed by a besieging force rather than surrender some weapons entrusted to his safe-keeping by Imru’ al-Qays.46 Similarly, Ibn al-Dughannah, the chief of Qārah tribe who had given protection to Abu Bakr during Meccan phase of Islam, is quoted to have said ‘I do not wish the Arabs to hear that I violated an undertaking that I had granted to any man’.47 He was afraid of public opinion if he did not fulfil the expectations of muru’ah.

Arabs did a variety of jobs. All trades were not considered of equal status by society. Arab mind could arrange them in hierarchal form. Some jobs were superior to others. Most menial work one could be compelled to do, in their social belief, was manual labour. Manual labourers were called masiykhiya (those who bow) in Yamama.48 Hassan bin Thabit, a pre-Islamic poet who later became ‘poet laureate’ of the Prophet, curses his opponent in this manner: “your father was a blacksmith, and even worse, you are the slave of a blacksmith.”49 This is the reason trades were reserved for either Jews or non-Arabs like Persians or slaves.50

Pre-Islamic poet Labīd once spoke of a leader from his own clan as ‘one of a tribe whose forefathers laid down for them a sunnah (سنه), and every folk has a sunnah and its imām (امام). Here Labid refers to the established customary practice of each tribe having a sunnah and an imam. Imam is the tribal hero whose actions set a precedent and example for others to follow. This precedent is called Sunnah.51 Another pre-Islamic poet ‘Abīd elaborates this concept further: “we follow the ways of our forefathers; those who kindled wars and were faithful to the ties of kinship.53

Sunnah could only be modified in a tribal gathering and with the consensus of all full members. Attending such a gathering was a source of pride for a tribesman: “among them are assemblies of fine men, councils from which follow decisive works and deeds…; when you come to them, you will find them round their tents; in session, at which impetuous action is often obviated by their prudent members.”54 These assemblies had jurisdiction to hear criminal cases as well. “Yea, goodly is the Man, by my life, to whose protection thou mayst surely appeal, what time in the tribal assembly the crier (munādī) raises his cry!”55 Innocence or guilt was proven either by oath or contest or evidence.56 Probably pre-Islamic times needed two witnesses to establish a crime. It is evident from a South Arabian inscription noted by Schacht.57

A Tribal Gathering58

If you will not seek vengeance for your brother

Take off your weapons and fling them on the flinty ground;

Take up the eye pencil, don the camisole, dress yourselves in woman’s bodices!

What wretched kin you are to a kinsman oppressed!

You have been diverted from avenging your brother

By a bite of minced meat and a lick of meagre milk.61

This principle of blood for blood, talion and its substitute the blood money (paid in cattle), is known from ancient Middle Eastern civilizations. In pre-Islamic customary law, in contrast to Islamic law, not only the murderer but every member of his kinship was subject to talion. However, the talion extended to the clan and not to the whole tribe.62 Blood money during pre-Islamic times was one hundred camels.63

Another way to seek justice, in addition to the tribal council, was to agree upon an arbiter. He was respected for his nobility, integrity, trustworthiness, leadership, seniority, glory and experience.64 Arbiter did not have any force at his disposal. His judgement was honoured due to his personal respect: “the two conciliators from Ghaiz bin Murra laboured for peace after the tribe’s concord had been shattered by bloodshed; So I swear, by the Holy House about which circumambulate men of Quraysh and Jurhum, whose hands constructed it, a solemn oath I swear – you have proved yourselves fine masters in all matters, be the thread single or twisted double. You alone mended the rift between ‘Abs and Dhubyān after long slaughter and much grinding of the perfume of Manshim. And you declared: ‘if we achieve peace broad and sure by ample giving and fair speaking, we shall live secure,” says Zohayr, a pre-Islamic poet.65

One punishment, if somebody committed a crime against a member of his own kinship group, was banishing him from the protection of the tribe. This meant his blood was licit: “and somewhere the noble find a refuge afar from scathe, the outlaw a lonely spot where no kin with hatred burn. I, never a prudent man, night-faring in hope or fear, hard-pressed on the face of the earth, but still have room to turn. To me now, in default of you [my kin], are comrades a wolf untired, a sleek leopard, and a fell hyena with a shaggy mane. True comrades, they never let out the secret in trust with them, or forsake their friend just because he brought them bane” are the words of Shanfara, a pre-Islamic poet.66

Punishment of theft and adultery is often dealt with together in the earliest codes of law originating in the region of the Middle East.67 Adultery was a form of theft in the Middle Eastern mindset from the earliest times. Even punishment of stoning to death for committing adultery and chopping off a hand for theft can be traced back to the most ancient civilizations in Mesopotamia.68, 69 How nauseous did pre-Islamic Arabs feel about the act of adultery is evident from a Thmudic inscription written in Hejazi style and noted by Winnett and Reed. This inscription reads “and Z’G and Zufray have committed adultery; and this deed stinks worse than a stinking fart.”70

Stoning to death was punishment for adultery in pre-Islamic Arabs, as noted by Al-‘Askari (d. 1005 CE) in Awa’il, “the first to stone for zinā was Rabī’a bin Ḥiḍar al-Asadi : this is to say that a woman from among them [i.e. from the Bani Asad] fell in love with a man and employed – in order to elope with him – the deceptive delusion that she had died. Then some of her tribe ran into her, and, recognizing her, put the issue [of her deception] before Rabī’a bin Ḥiḍar al-Asadi who ordered her lapidation; thus was she stoned. It is [furthermore] mentioned that she had feigned illness, then death, and thus was she carried to her tomb and buried. Then when the people dispersed, her paramour took pity on her, so unburied her and carried her off, but God only knows.”71

Pre-Islamic Arabs used to chop off hands of thieves. In one anecdote recorded by Ibn Ishaq, Quraysh chopped off the hand of Duwayk, a freedman of Mulayḥ clan of Khuzā’ah for being involved in the theft of treasure from Ka’ba in pre-Islamic times.72 Awa’il literature attributes the first cutting of the hands to a well-known Quraysh Shaykh: “the first to cut for theft was Walīd bin Mughīrah. The messenger of Allah, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, cut in Islam, and the Qurʾān revealed it in His speech, exalted be He: ‘the male thief and the female thief: cut off their hands’ [al-Ma’ida: 38]. And the Quraysh used to prescribe that as well.73 Shahrastani gives details in Al-Milal wa’l-Niḥal: ‘and they used to cut off the right hand of the thief if he stole.’74 A hadith recorded by Bukhārī in his Ṣaḥīḥ confirms it: “Narrated ‘Urwah bin az-Zubair: A lady committed theft during the lifetime of Allah’s Messenger in the Ghazwa of Al-fath, [i.e. conquest of Mecca]. Her folk went to Usāma bin Zayd to intercede for her [with the Prophet]. When Usāma interceded for her with Allah’s Messenger, the colour of the face of Allah’s Messenger changed and he said, “Do you intercede with me in a matter involving one of the legal punishments prescribed by Allah?” Usāma said, “O Allah’s Messenger! Ask Allah’s forgiveness for me.” So in the afternoon, Allah’s Messenger got up and addressed the people. He praised Allah as He deserved and then said, “Amma Ba’du [then after]! The nations before you were destroyed because if a noble amongst them stole, they used to excuse him, and if a poor person amongst them stole, they would apply [Allah’s] legal punishment to him. By Him in Whose Hand Muhammad’s sole is, if Fatima, the daughter of Muhammad stole, I would cut her hand.”75

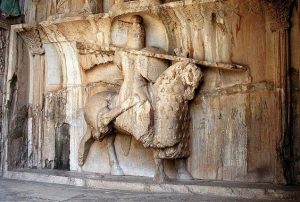

Engraving of Khusro II at Taq e Bostan.76

Helmet, Coat of Mail and Lancet can be seen

Poetry was the main literary expression of pre-Islamic Arabs in the centuries immediately preceding Islam. It was the political voice of a tribe. Poetry had achieved such a social prestige that every tribe of significance had to have a poet laureate. Poets were like journalists of the day and no political entity could afford to be devoid of them. Competitions of poetry were held regularly. No modern critic has ever doubted the eloquence of pre-Islamic Arabic poetry. It mesmerized the minds and souls of Arabs. One taunt of a poet could lead to bloodshed. Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry was a reflection of their tribal life. It dealt with heroic deeds in war and peace and told legends of ancestors and of tribal migration.79 On a lighter note, Arabic poetry from the pre-Islamic era has an abundance of praise for the beauty of the beloved one and the serenity of nature. Its verses have preserved forever the social customs and general thinking patterns of the people for whom it was created.80

A Bedouin tent81

Nomads needed only temporary shelters to live in. They have not left any archaeological trace of their camps. An account from pre-Islamic Arab poetry demonstrates why it was almost impossible for a camp to survive for archaeologists. ‘Still to see are the traces at ad-Dafīn…; every valley and pasture once full of people; the abode of a tribe whom past time has smitten; their dwellings show now like patterns on sword sheaths; desolate all, save for ashes extinguished; and leaving of rubbish and ridges of shelters; shreds of tethering ropes, and a trench round the camp; and lines plotted out, changed by long year’s lapse.”84

Here is an account of temporary shelter made for men on the expedition: “many a tent in whose sides the fresh wind blows; in a spacious country, the door of which is never closed; its awning made of worn-out embroidered garments; while the inner covering is of striped Athami cloth; having for ropes the halters of short-haired horses; straight like lance-shafts, returning from a first or second raid; such tents have I raised over men both young and hoary; whose lances cause blood to flow from the enemies’ veins.”85 The settled inhabitants of Arabia favoured stone or mud-brick dwellings.

Mabiyat village, Saudi Arabia 86 Mud Brick houses from 6th Century CE.

Viner’s house made up of stone: 6th Century CE89

Qasr Marid: Domat al Jandal. C, 6th Century CE91

Ghumdan Palace, Sana’a92

Bedouin hunter and his leopard 94

Pre-Islamic Arabs needed entertainment too and had devised means to fulfill the need. Poetry contests, that took place on occasions of the market, have already been mentioned. One favourite pastime of affluent Arabs was hunting. Though hunting was partly practiced to supplement food, its main purpose was to practice archery to get fame. The hunter was armed with a bow and arrow and was aided in the chase by the cheetah, the caracal lynx, or more commonly the hound. A beautiful pre-Islamic ode testifies:

In his fright he [the oryx] turns to escape and finds the way blocked by dogs well trained;

Two with hanging ears, crop-eared the third;

With their teeth they grip him, but stoutly thrusts he the hounds away;

A defender sturdy of leg, his long sides streaked with brown;

Sideways he turns to bring into play horns sharp as steel;

On them the blood shines red and bright as Socotra’s dye;

Two spits they seem, fresh cut to skewer the feasters’ meat;

drawn off before it is thoroughly cooked, as he thrusts them quick;

Till at last when all of the pack were checked, a good handful slain, and rest dispersed, yelping with pain;

Stood forth the master to save his hounds, in his hand a sheaf of slender arrows with shining points, feathers cut lose;

Then he shot, if haply the remnant escape: and the arrow sped;

And the bitter shaft transfixed the Oryx from side to side;

headlong he crashed, as a camel stallion falls outworn in the hollow ground,

but the oryx was fairer and goodlier far.” 96

Wine drinking was another social event for them. Here is a passionate description of wine by a pre-Islamic poet:

‘a captive, it dwelt in the jar for twenty revolving years;

above it a seal of clay, exposed the wind and sun;

imprisoned by Jews who brought it from Golan in land afar and offered;

for sale by a vintner who knew well to follow gain.97

Consumption of wine was not limited to drinking alone at home and in parties of personal guests. All Arab settlements had taverns:

Many a time I hastened early to the tavern;

while there ran at my heels a ready cook, a nimble active serving-man;

Midst a gallant troop, like Indian scimitars, of mettle high;

Well they know that every mortal, shod and bare alike, must die;

Propped at ease I greet them gaily, them with myrtle boughs I greet;

pass among them wine that gushes from the jar’s mouth bitter-sweat;

Emptying goblet after goblet, but the source may no man drain;

never cease they from carousing save to cry, ‘fill up again!’;

Briskly runs the page to serve them: on his ears hang pearls, below;

tight the girdle draws his doublet as he bustles to and fro;

‘Twas as though the harp waked the lute’s responsive note;

When the loose-robed chantress touched it, singing shrill with quavering throat;

Here and there, among the party, damsels fair superbly glide;

each her long white skirt lets trail and swings a wineskin at the side.98

Pre-Islamic Arabs used to bet.99 It could have provided delight to a selected few.

Ancient grave, H.a’il 100

End Notes:

- Kurkh Stela (named after location of discovery). Currently at British Museum. Identification: 118883.

- Daniel D. Luckenbill. Ancient records of Assyria and Babylonia (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1926), vol. I P 223. See also: Adolf Leo Oppenheim, “Babylonian and Assyrian Historical texts,” in Ancient Near Eastern Texts: relating to the Old Testament, ed. James B Pritchard Princeton, (Princeton University Press, 1969), 279.

- Tombstone of Matmat. Currently in a private collection in Virginia. First described and translated by: A. Jamme, W. F. Sabean and Hasaean Inscriptions from Saudi Arabia (Universita di Roma: Instituto Di Studi Del Vicino Oriente, 1966), 74, Pl. XVII.

- Beatrice Gruendler. The development of the Arabic Scripts: From the Nabatean Era to the First Islamic Century According to the Dated Texts; Harvard Semitic Series No 43. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1993.

- Albert W. F. Jamme. Sabaean and Hasaean inscriptions from Saudi Arabia. Rome: Istituto di studi del Vicino Oriente, 1966 .

- Livingstone, A. “linguistic, tribal and onomastical study of the Hasaean inscriptions,” The Journal of Saudi Arabian Archaeology 8 (1984): 86-108.

- Rukash inscription, current location: Maidan Saleh, Saudi Arabia. Discovered by Jaussen and Savignac in period from 1909 to 1914.

- John F. Healey and G. R. Smith. “Jaussenn-Savignac 17 – The earliest Dated Arabic Document (A.D. 267).” The Journal of Saudi Arabian Archaeology 12 (1989): 77-84. For the picture see plate 46.

- Christian Julien Robin, “Antiquity” in Roads of Arabia, ed. ‘Ali ibn Ibrāhīm Ghabbān, Beatrice Andre-Salvini Francoise Demange, Carine Juvin and Marianne Cotty (Paris: Louvre, 2010), 86.

- Michael C. A. Macdonald, “Reflections on the linguistic map of pre-Islamic Arabia,” Arabian Archaeology and epigraphy 11 (2000): 57.

- Francis E. Peters. The Arabs and Arabia on the Eve of Islam: The Formation of the Classical Islamic World, (Surrey: Ashgate, 2010), XIII.

- For the way Arabs were called by neighbours see: Procopius. History of the Wars, Books I and II, ed. and trans. H. B. Dewing (London: William Heinemann, 1914), 159.

- Prophet Muhammad is the founder of Islam

- For the event see: Muhammad Ibn Ishaq. The life of Muhammad, ed. and trans. Alfred Guillaume (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2013), 646.

- Gustave E. Grunebaum, “The nature of Arab Unity before Islam.” Arabica 10, no. 1 (1963): 20.

- Abdullah al-Askar. Al-Yamama: in the Early Islamic Era, (Riyadh: King Abdul Aziz Foundation, 2002), 3.

- Fred M. Donner, “The Role of Nomads in the Near East in Late Antiquity (400 – 800 C.E.),” in Traditions and innovation in Late Antiquity, eds. Clover F.M. and R. S. Humphreys (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1989), 80.

- Genealogy of Sharifians. Current location: Mamma Haidara Commemorative Library, Timbuktu.

- Robert G. Hoyland. Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam, (New York: Routledge, 2001), 251.

- Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabri. Tarikh al-Rusul wa’l-Muluk, ed. and trans. Ella Landau- Tasseronn, (New York: State University of New York Press, 1998), Vol. 39, P 7.

- Robert G. Hoyland. Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam, (New York: Routledge, 2001), 118.

- A pre-Islamic poet Ḥārith bin Wa’lah uses the word mujāwir for the one who is under protection. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Martin Hinds (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 8.). The root of mujawir is jiran.

- Muhammad ibn jarir al-Tabari. Ta’rīkh al-Rusul wa-l-Mulūk, 3 series, ed. M. J. de Goeje et. Al. (Linden, Brill, 1897 – 1901; Tranns. The History of al-Tabri, 39 vols. Albay, SUNY, 1985 – 99.

- Walter A. Dostal, “Mecca before the Time of the Prophet – Attempt of an Anthropological interpretation,” Der Islam: Journal of the History and Culture of the Middle East 68, no. 2 (1991): 212.

- Warner Caskel, “The Bedouinization of Arabia.” American Anthropologist 52, no. 2, part 2, memoir no. 76 (1954): 37.

- Matson (G. Eric and Edith) photograph. Current location: Library of Congress, Washington. ID matpc.03798. shot between 1934 to 1939 in Palestine

- Walter A. Dostal, “Mecca before the Time of the Prophet – Attempt of an Anthropological interpretation.” Der Islam: Journal of the History and Culture of the Middle East 68, no. 2 (1991): 115.

- Louis Cheikh. Kitāb Shu’arh’ al-Nasrāniyya, (Beirut: Jesuit Fathers, 1890), vol. I, P 162. For English translation see: Suzanne P. Stetkevych. The Mute Immortals Speak: Pre-Islamic Poetry and the Poetics of Ritual, (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1993), 206 – 38.

- Francis E. Peters. The Arabs and Arabia on the Eve of Islam: The Formation of the Classical Islamic World, (Surrey: Ashgate, 2010), xiv.

- Classification of the whole population into either nomads or sedentary will be an oversimplification. Donner points out that many had dual characters. They took to grazing when the climate was favourable and returned to settlements when the climate was not conducive to grazing. Donner also argues that members of certain fully nomadic tribes owned orchards in settlements as well, for example, Tamīm (Fred M. Donner, The Early Islamic Conquests (Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 1981), 16).

- Probably in Jerusalem

- Warner Caskel, “The Bedouinization of Arabia,” American Anthropologist 52, no. 2, part 2, memoir no. 76 (1954): 46

- Warner Caskel, “The Bedouinization of Arabia,” American Anthropologist 52, no. 2, part 2, memoir no. 76 (1954): 38

- Abdullah al-Askar. Al-Yamama: in the Early Islamic Era, (Riyadh: King Abdul Aziz Foundation, 2002), 33

- Warner Caskel, “The Bedouinization of Arabia,” American Anthropologist 52, no. 2, part 2, memoir no. 76 (1954): 35

- Fred M. Donner, “The Role of Nomads in the Near East in Late Antiquity (400 – 800 C.E.),” in Traditions and innovation in Late Antiquity, eds. Clover F.M. and R. S. Humphreys (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1989), 73

- Gustave E. Grunebaum, “The nature of Arab Unity before Islam.” Arabica 10, no. 1 (1963): 18 – 19

- Bedouin couple from Adwan tribe pose in front of their tent. Shot somewhere between 1898 and 1914. Photographer unknown.

- Probably in Saudi Arabia

- Ammianus Marcellinus. Ammianus Marcellinus in three volumes, ed. and trans. Johnn. C. Rolfe, (London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1935), 27-28.

- Photo of Bedouins eating a shared food is from Sinai shot by Ruth Shilling.

- Gustave E. Grunebaum, “The nature of Arab Unity before Islam,” Arabica 10, no. 1 (1963) 16.

- Irfan Shahīd. Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century, (Washington: Dumbarton Oaks, 2002), Vol. II part II, P 303.

- Hatim al-Ta’i. Der Dīwān des arabischen Dichters Hatim Tej, ed. and trans. Friedrich Schulthess, (Leipzig, Hinrichs, 1897), 62

- ‘Amr ibn Qami’ah. The Poems of ‘Amr son of Qami’ah, ed. and trans. Charles J. Lyall, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1919), 53. By the way, this Lyall is the same person in whose name Lyallpur, a city in Pakistan was christened.

- Montgomery W. Watt. Muhammad at Mecca, (London: Oxford University Press, 1953; Repr. 1965), 21.

- Ma‘mar ibn Rāshid. The Expeditions, ed. Joseph E. Lowry, trans. Sean W. Anthony (New York: New York University Press, 2015), 73.

- Sayyid Murtada al Zubaydi. Taj al-‘Urus (Kuwait: Matba’at al- Ḥukuma, 1965), vol. VI, P 58.

- Ḥassān bin Thābit. The Dīwan of Hassān B. Thābit, ed. Hartwig Hirschfeld (Leyden: E. J. W. Gibb Memorial, 1910), 127, 48.

- Robert G. Hoyland. Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam (New York: Routledge, 2001), 117, 118.

- Arthur J. Arberry. The Seven Odes: The First Chapter in Arabic Literature. (London, George Allen and Unwin Ltc., 1957), 147. For the Original Arabic ode see: Labid. Diwān, ed. I. Abbas (Kuwait: Wizarat al-Irshad wa-l-Anba’, 1962). See also: C. J. Lyall. A Commentary on ten ancient Arabic poems (Calcutta: 1894). See also: C. J. Lyall. Translations of ancient Arabian Poetry (London: Williams and Norgate, 1930). And see also: A. F. L. Beeston, “An experiment with Labid”, Journal of Arabic Literature 7 (1976): 1 – 6 (Labid). For comments on sunnah and imam in pre-Islamic times see: Gustave E. Grunebaum, “The nature of Arab Unity before Islam,” Arabica 10, no. 1 (1963): 15.

- ‘Abid ibn al-Abras. The Dīwāns of ‘Abid ibn al-Abras., of Asad, and ‘Āmir ibh aṭ–Ṭufail, of ‘Amir ibn Ṣa’ṣa’ah, ed. and trans. Charles Lyall (Leyden, E. J. W. Gibb Memorial, 1913), 48 (ode 20).[/nete] This signifies how important it was for the Arabs to follow the sunnah of their forefathers. Another term used in lieu of sunnah was ‘dīn al-‘Arab’ (the ways of the Arabs). Deviating from sunnah did not risk any religious punishment like the anger of gods or spirits or problems in the afterlife. In that sense sunnah was the secular unwritten ethos and abiding by it was honour (ird.) of an Arab.52Gustave E. Grunebaum, “The nature of Arab Unity before Islam,” Arabica 10, no. 1 (1963): 15.

- Zuhyr ibn Abi Sulma. Dīwān, ed. K. al-Bustani (Beirut: Dar al-Sader, 1964), 62.

- ‘Amr ibn Qami’ah. The Poems of ‘Amr son of Qami’ah, ed. and trans. Charles J. Lyall (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1919), 13.

- See an example in poetry: Zuhyr ibn Abi Sulma. Dīwān, ed. K. al-Bustani (Beirut: Dar al-Sader, 1964), 12.

- Joseph Schacht. Introduction to Islamic Law (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1950), 9.

- Bedouin wedding gathering. 1934. Photo credit: Kluger Zoltan.

- Hudhaliyyun. Dīwān, ed. Johann G. L. Kosegarten (London: Oreintal Translation Fund, 1854) (nos 1 – 138); Ed. and Trans. J Wellhausen in his Skizzen and Vorarbeiten I, Berlin, Georg Reimer, 1884 (nos 139-).89.

- Tufail ibn ‘Auf. The Poems of Tufail ibn auf Al-Ghanawi and At-tirimmah ibn Hakim At-Tayi, ed. and trans. Fritz J. H. Krenkow (London: E. J. W. Gibb Memorial, 1927), 3.

- Abu Tammām. Dīwān al- Ḥamāsa ta’līf Abī Tammām, ed. Salih, A. A. (Baghdad, Dar al-shu’un al-Thaqafiyya al-‘Amma, 1987), 684

- Warner Caskel, “The Bedouinization of Arabia,” American Anthropologist 52, no. 2, part 2, memoir no. 76 (1954): 36.

- Arthur J. Arberry. The Seven Odes: The First Chapter in Arabic Literature (London, George Allen and Unwin Ltc., 1957), 115.

- Ahmad ibn Abi Ya’qub al-Ya’qubi. Tarīkh, ed. Martijn T. Houstma (Leide: Brill, 1883), vol. 1, P 299.

- Arthur J. Arberry. The Seven Odes: The First Chapter in Arabic Literature (London, George Allen and Unwin Ltc., 1957), 115 (Zohayr’s mualliqa).

- Shanfara. Dīwān, ed. I. B. Ya’qub (Beirut: Dār al-Kitāb al-‘Arabyy, 1991).

- Walter Young, “Stoning and Hand-amputation: the pre-Islamic Origins of the Hadd penalties for Zina and Sariqa,” Master’s thesis, Institute of Islamic Studies (Montreal: McGill University, September 2005): 7.

- Wael b. Hallaq. The formation of Islamic Law (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004).

- The first mention of stoning as a method of execution comes from the very first criminal code known to us – Urukagina’s reforms (c. 2400 B.C) – a Mesopotamian law. It states that if a woman takes more than one husband she is liable to be stoned. (Versteeg, Russ. Early Mesopotamian Law (Durham: Carolina Academic Press, 2000), 18). Interestingly, the punishment is for a sexual crime. One of the epigraphic decrees discovered by Dr. Jabir Ibrahim at Hatra (Ibr. 1) dates from “the month KNWN of [the year] 463,” i.e. “December 151 CE – January 152” (Segal, J. B., “Aramaic Legal Texts from Harta,” Journal of Jewish Studies 33, nos. 1 – 2 (1982): 110, in. 1) and rules “that anyone who will steal inside this store and inside the outer wall, if he is a man of the community he shall be killed by the death of the god, and if he is a foreigner he shall be stoned,” This is the earliest epigraphic evidence of stoning. And it is produced by Arabs of Hatra.

Probably stoning to death as the punishment for sexual crimes in Judaic traditions early in their history. Deuteronomic Code is part of ancient Judaic law. Discussing if a husband finds after marriage that his wife is not virgin it states in Deut. 22: 20 – 1: ‘if, however, the charge is true and no proof of the girl’s virginity can be found, she shall be brought to the door of her father’s house and there the men of the town shall stone her to death. In Deut. 22: 23 – 4 it states: if a man happens to meet in a town a virgin pledged to be married and he sleeps with her, you shall take both of them to the gate of that town and stone them to death.” Both are written in: The Holy Bible: New International Version. (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan Bible Publishers, 1980), 210. Once the Jewish power to pronounce or inflict capital punishment had been lost, the punishment of adultery was modified into the divorce of the woman. (Abrahams, I. “Adultery (Jewish),” Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics ( New York 1951 – 1957), Vol I, P 130). See also: Grubbs, Judith Evans. Law and Family in Late Antiquity: The Emperor Constantine’s Marriage Legislation (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995), 243.

The earliest example of chopping off a hand for theft comes from code 253 of Hammurabi’s law: if a man hire a man to oversee his farm and furnish him the seed grain and entrust him with oxen and contracts with him to cultivate the field, and that man steal either the seed or the crop and it is found in his possession, they shall cut off his fingers. (Harper, Robert Francis. The Code of Hammurabi, King of Babylon about 2250 C.C. (Chicago: UP, 171), 89.)

- Frederick V. Winnett and W. L. Reed. Ancient Records from North Arabia (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1970), 110.

- Abu Hilal al-Ḥasan ibn ‘Abd Allāh Al-‘Askari. Kitāb al-Awāil, ed. Muḥammad al-Sayyid al-Wakīl (Medina: 1385/1966), 49.

- Muhammad Ibn Ishaq. The life of Muhammad, ed. and trans. Alfred Guillaume. (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2013), 79.

- Abu Hilal al-Ḥasan ibn ‘Abd Allāh Al-‘Askari. Kitāb al-Awāil, ed. Muḥammad al-Sayyid al-Wakīl (Medina: 1385/1966), 34.

- Abū Al-Fath Muḥammad ibn ‘Abd al-Karīm Al- Shahrastani. Kitāb al-Fasl fi al-Milal wa-al-Ahwa’ wa-al-Nihal (Al-Qhirah: 1899) Vol. II, Sec. 3, P537.

- Muḥammad ibn Ismā’il al- Bukhari. Sahīh al-Bukhāri, trans. Muhammad Muhsin Khan (Riyadh: Darussalam, 1997), vol 5, Hadith number 4304, P 361, 62.

- Herzfeld, Ernst, “Khusrauparawez und der Taq-ivastan,” Archaeologische Mitteilungen aus Iran 9, no. 2 (1938): 91 – 158.

- Muhammad Ibn Ishaq. The life of Muhammad, ed. and trans. Alfred Guillaume (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2013), 169.

- Anthony Sean W., “the domestic origins of imprisonment: an Inquiry into an Early Islamic Institution, ” Journal of American Oriental Society 129 (2009): 571 – 96.

- Warner Caskel, “The Bedouinization of Arabia,” American Anthropologist 52, no. 2, part 2, memoir no. 76 (1954): 37.

- Women poets are known from Pre-Islamic times. See: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXI, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Michael Fishbein (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 51.

- Cheese being dried on tent roof can be seen. Photo of Arakat tribe shot between 1898 and 1946. Photographer unknown.

- Warner Caskel, “The Bedouinization of Arabia,” American Anthropologist 52, no. 2, part 2, memoir no. 76 (1954): 40.

- David S. Margoliouth. Muhammad and the rise of Islam (New York: knickerbocker press,1905), 192.

- ‘Abid ibn al-Abras. The Dīwāns of ‘Abid ibn al-Abraṣ, of Asad, and ‘Āmir ibn aṭ– Ṭufail, of ‘Amir ibn Ṣa’ṣa’ah, ed. and trans. Charles Lyall (Leyden, E. J. W. Gibb Memorial, 1913), 84 (ode 11).

- Tufail ibn ‘Auf. The Poems of Tufail ibn auf Al-Ghanawi and At-tirimmah ibn Hakim At-Tayi, ed. and trans. Fritz J. H. Krenkow (London: E. J. W. Gibb Memorial, 1927), 1.

- ‘Abdallah bin Ibrahim al-‘Umayr, in “Al-Mabiyat: the Islamic town of Qurh,” in Roads of Arabia, ed. ‘Ali ibn Ibrāhīm Ghabbān, Beatrice Andre-Salvini Francoise Demange, Carine Juvin and Marianne Cotty, (Paris: Louvre, 2010) 463. Photo credit: Silvija Sares.

- Charles M. Doughty. Travels in Arabia Deserta (New York: Random House, Repr. 1921), Vol II, P 446.

- Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad ibn Jubayr. The Travels of ibn Jubayr: Being the chronicle of a medieval Spanish Moor concerning his journey to the Egypt of Saladin, the holy cities of Arabia, Baghdad the city of the caliphs, the Latin kingdom of Jerusalem and the Norman kingdom of Sicily, ed. and trans. Roland J.C.Broadhurst (London: Johathan Cape, 1952), 206.

- Bedouin of Shammar tribe in Iraq, 1925. This Asiatic leopard is critically endangered. Photographer unknown

- ‘Umar. Sa’d bin Abdulaziz Al-Rashid, “The discovery of Al-Rabadha,” in Roads of Arabia, ed. ‘Ali ibn Ibrāhīm Ghabbān, Beatrice Andre-Salvini Francoise Demange, Carine Juvin and Marianne Cotty, (Paris: Louvre, 2010), 438.

- Qasr Marid at Domat al Jandal archaeological ruins. Four minarets are visible. Exact period of construction is not known but it could be from 6th century CE as archaeologists have established the site’s occupation during 6th century. (‘Ali ibn Ibrāhīm Ghabbān, Beatrice Andre-Salvini Francoise Demange, Carine Juvin and Marianne Cotty. Roads of Arabia (Paris: Louvre, 2010)

- Modern Sana’a

- Ḥasan ibn Aḥmad al- Hamdani. Kitāb al-iklīl volume 8. ed. A. M. al-Karmali, (Baghdad, Darr al-Salam, 1931); Trans. Amin N. Faris, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1938) as The Antiquities of South Arabia, 15, 22-25.

- Bedouin of Shammar tribe in Iraq, 1925. This Asiatic leopard is critically endangered. Photographer unknown

- Al-Mufaḍḍal son of Muhammad. The Mufaddaliiyat: An Anthology of Ancient Arabian Odes. Vol. II, ed. and trans. Charles J. Lyall (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1918), Ode no. 52, poet: Aswad ibn Ya’fur, P 163.

- Al-Mufaḍḍal son of Muhammad. The Mufaddaliiyat: An Anthology of Ancient Arabian Odes. Vol. II, ed. and trans. Charles J. Lyall (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1918), Ode no. 126, poet: Khuwailid son of Khālid, P 358

- Al- Mufaḍḍal son of Muhammad. The Mufaddaliiyat: An Anthology of Ancient Arabian Odes. Vol. II, ed. and trans. Charles J. Lyall (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1918), Ode no. 55, poet: Rabi’ah son of Sufyān, P 187.

- Maymun bin Qays al-A’sha. Diwan al-A’sha al-Kabir, ed. M. M. Husayn. (Beirut: Dar al-Nahdha al-Arabiya, 1972).

- Muhammad bin ‘Umar al-Wāqidī. The life of Muḥammad: kitāb al-Maghāzī, ed. Rizwi Faizer, trans. Rizwi Faizer, Amal Ismail and AbdulKader Tayob (London: Routledge, 2011), 345.

- Ancient grave inside a compound called Qasr Tuwarin, located in Tuwarin village near Ḥaʾil, Saudi Arabia. The grave is claimed to be that of Ḥātim al-Ṭai but no archaeological work has ever been done on it. On the other hand, according to 17th Century orientalist D’Herbelot, Tai’s tomb is located at a small village called Anwarz in Arabia (Arbuthnot, F. F. Persian Portraits: A Sketch of Persian History, Literature and Politics (B. Quaritch: 1887), 132.

- ‘Abid ibn al-Abras. The Dīwāns of ‘Abid ibn al-Abraṣ, of Asad, and ‘Āmir ibh aṭ–Ṭufail, of ‘Amir ibn Ṣa’ṣa’ah, ed. and trans. Charles Lyall (Leyden, E. J. W. Gibb Memorial, 1913), 60 (ode 28).

- Al-Mufaḍḍal the son of Muhammad. The Mufaddaliiyat: An Anthology of Ancient Arabian Odes. Vol. II, ed. and trans. Charles J Lyall (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1918), Ode no. 80, poet: Sha’s son of Nahār, P 239.

- ‘Abd al-Razzaq al-San’ani. Muṣannaf, 11 vols. ed. Habīb al-Rahmān al-A’zami (Beirut: al-Majlis al-‘Ilmi, 1970 – 72), vol. 3, P 500.