By the 4th century CE, the overwhelming majority of inhabitants in Arabia were polytheists. 1 Gradually monotheism diffused into them by the 5th and 6th centuries CE. Both of the main monotheist traditions of that time, Judaism and Christianity, established themselves among pre-Islamic Arabs. In addition, Zoroastrianism started making inroads as well.

Jews

The first archaeological proof of Jewish presence in the Arabian Peninsula comes from a tombstone in Madain Saleh erected in 42 CE by a certain Shubayt who explicitly describes himself as a Jew. 2 Therefore, Jews were the earliest monotheists in Arabia.

Jews believe in a single God whose name in Hebrew is “YHWH” meaning ‘I am’. They believe that Yahweh formed man by two impulses, ‘yetzer tov’ and yetzer ra. Jew scripture has very little to say about what will happen after death, which is contrary to Islam and Christianity. Torah, also called Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, is their most important text. It contains ten commandants which deal with believing in one God, honouring Sabbath, respecting parents, forbidding murder, adultery, stealing, giving false testimony, and coveting fellow’s possessions. Talmud is another sacred book exploring Torah. According to Jewish beliefs, Yhwh has made a certain covenant with the children of Israel. Authority in religious matters is not vested in one person but in scripture which is explained by Rabbis. Jews pray three times a day with a fourth prayer added on Sabbath day. Observant Jews recite prayers before eating, drinking etc. Jew’s prayer gestures resemble Muslim gestures of prayer. They have standing like qyam (قيام), kneeling like rukoo’ (ركوع) and prostrating like sajdāh (سجده). They do ablution before prayer which is also similar to that of Muslims. They believe in Messiah who will come in future to guide the right way to people who are sinful. One of the Jew’s festivals is Yom-Kippur which involves fasting. They strictly restrict themselves to eating kosher.3

The origin of Jews in Hejaz is a puzzling matter and has been discussed in the section of politics. In addition to the Jews of Hejaz, there was another group of Jews residing in the south. The earliest evidence of Jewish presence in South Arabia comes from the account of a Christian missionary Theophilus the Indian, who accompanied the ambassadors of the Byzantine emperor Constantinus (337 -61 CE) to the ruler of Himyar. He encountered Jews there.4 Probably Judaism in the south was limited to the ruling elite who had converted to it. Jews were not limited to northern Hejaz and Yemen. They were significantly powerful in these two regions. Otherwise, they were scatted as a minority all over. Baladhuri describes their presence in pre-Islamic Bahrain.5 None of the nomadic tribes has been described as being Jew, prompting speculation that Judaism had gained grounds among settled Arabs only.

Christians

Another monotheist group in pre-Islamic Arabia was Christians. The earliest reliable evidence of the presence of Christianity among Arabs is a dated inscription from 318 CE found in the archaeological remains of a Marcionist Christian church in Deir Ali (present day southern Syria). The inscription reads ‘the meeting-house of the Marcionists, in the village of Lebaba, of the Lord and Saviour Jesus the God—Erected by the forethought of Paul a presbyter, in the year 630.”6 Geographical distribution of churches and Christian inscriptions discovered by archaeologists and extant writings of both contemporary and early Islamic sources establish that Christians had rooted themselves in Iraq, Syria, Bahrain, Yamama and Yemen.7 In addition, they had pockets of followers spread all over the Arabian Peninsula where Christianity had infused into many Bedouin tribes.8 Najran and Sana’a both were influential Christian centers.9 Abode of a Christian group in pre-Islamic Mecca can scarcely be doubted. The Qur’an calls them ‘Naṣārah’(نصارہ). Warqa bin Nofel, the cousin of Khadija, is a vivid example.

Christians believe in God – the Father, Jesus – the son and the Holy Spirit. The trio makes what they call ‘Trinity.’ Their scripture is Bible (Injīl). They believe in the Day of Judgement and that pious souls will go to Heaven and evil souls will go to Hell. They also believe in Satan who will be thrown into a lake of fire on the Day of Judgement. In Christian traditions, regular public worship, performed in a church, is complemented by worship in private and in small groups such as meditation, prayer and study.10, 11

Zoroastrians

Zoroastrianism reached the Arabian Peninsula after its origin in Persia. It was mainly practised by expatriate Iranians living and working in the Arabian Peninsula. 12 Two prominent Zoroastrian families of Iranian origin living in Yamama were Ben Karman and Ahmar. Two temples of fire worship were located near the mine of Shamam in Yamama.13 Iranians residing in Bahrain practiced Zoroastrianism and built their fire temple there.14 They had a sizable presence in Yemen as well.15

The Supreme Being in Zoroastrian’s belief system is complex. Basically, it is Zaran Akaran that is timeless and boundless but its manifestation is Ahura Mazda, the ‘Wise Lord’. From Ahura Mazda come twin spirits of Spenta Mainyu (Bountiful spirit) and Angra Mainyu (Destructive spirit). These two spirits, along with Ahura Mazda, create a kind of trinity. They believe fire is a symbol of Ahura Mazda and worship it in their temples. Their basic prayer is Ashem Vohu, performed daily. Their scripture is Avesta. They believe in Yazatas (angels). They believe in life after death. Good souls go to heaven called Vahishta Ahu and evil souls go to hell called Achista Ahu.16, 17

Pagans

Probably the biggest and most widespread religion of pre-Islamic Arabia was polytheism (pagan مشرکون). No inscription written by polytheists has ever come to light up till now.18 Even pre-Islamic poetry is largely silent on the religious traditions of pagan Arabs because its central theme was tribal honour, not religion.19 In absence of any conclusive archaeological evidence of Hejazi pagan practices, Ibn al Kalbi (d. 821 – 822 CE) remains the principal source of pre-Islamic Meccan paganism.20 Due to sketchy evidence, we can get only glimpses of pagan Arab religion and it is impossible to reconstruct the whole picture.

It is known that the pagans worshiped raw unpolished stones. Stone worship in Arabia was centuries old. The earliest testimony to stone worship in Arabia comes from writings of second century CE philosopher Maximus of Tyre and his contemporary Clement of Alexandria.21 Pagans also worshiped statues and images. According to Ibn al Kalbi if a statue were made of wood, gold or silver after the human form, it would be called ṣanam (صنم) but if it were made of stone it would be awṣān (اوصان).22 Kalbi reports that the Arabs were passionately fond of worshipping idols. Some of them took unto themselves a temple around which they centred their worship, while others adopted an idol to which they offered their adoration. A person unable to build himself a temple or adopt an idol would erect a stone in front of the Sacred House or in front of any other temple which he might prefer and then circumambulate it in the same manner in which he would circumambulate the Sacred House. The Arabs called these stones anṣāb (baetyls انصاب). The act of circumambulating them was called dawar (دوار). Whenever a traveller stopped at a place or station in order to rest or spend the night, he would select for himself four stones, pick out the finest among them and adopt it as his god, and use the remaining three as supports for his cooking. On his departure, he would leave them behind and would do the same on his other stops. Arabs offered sacrifices before all those idols, baetyls and stones, nevertheless, they were aware of the excellence and superiority of the Ka’ba, to which they went on pilgrimage and visitation. What they did on their travels was a perpetuation of what they did at the ka’ba, because of their devotion to it.23

Some scholars have suggested that pre-Islamic pagans worshiped stars but no authentic evidence is available at present to support this assertion.24

It appears that they worshipped three different kinds of idols; ‘Clan idols’ worshiped by the whole clan, ‘idols held by noblemen’ and ‘lesser idols’ of a domestic family cult which were presumably part of every household. Idols of the former category had names but those of the domestic category were anonymous.25 Scientific study of fetishism as a religious phenomenon has revealed that the material object is not venerated for itself but rather as the dwelling of either a personal being (god or spirit) or a force.26 Anṣab, aṣnam and awṣan could represent gods and spirits but it appears that pagan Arabs attached spiritual significance to those objects themselves. They were not only symbolic representatives of a supernatural being but were sacred on their own merit. Clan idols were permanent objects, having a proper name, were reverenced, and kept safe and protected. Since worship of a particular idol was closely connected with the tribal leadership who protected it, the destruction of the idol (especially a clan idol) meant defying the protector’s leadership and undermining his authority. In other words, in the historical context, the destruction of idols was a political act in Prophet Muhammad’s struggle against Arab tribal leaders.27 Unsurprisingly, the stereotypical stories of conversion to Islam have a recurrent pattern of destruction of the idol by a former pagan (or by his friend). It signifies a break with past superstitions and past tribal leadership and symbolizes loyalty to the new faith.28

As polytheism is inherently tolerant of gods of others, religious wars were unheard of among pagan tribes of pre-Islamic Arabia.

Ibn al Kalbi reports that Quda’ah (Quḍā‘ah قضاعه), Lakhm and Judham (Judhām جذام) as well as people of Syria had an idol called Uqaysir to which they pilgrimmed and at which they shaved their heads. Then they mixed the hair with wheat. Hawazin used to frequent that place, they were poor so they took the whole thing, wheat, hair and lice, baked it and ate.29 Tasm and Judais from Yamama is said to have worshiped an Idol called Kuthra. It was destroyed by Nahshal bin Rabi’ bin ‘Arara as a symbol of his conversion before his departure to Medina to meet Prophet Muhammad.30 Aws and Khazraj, the Arab tribes of Yathrib, both worshiped idols.31 Ibn Ishaq reports that Mudar tribe used to worship Suwā’ And they had placed him in Ruhāṭ [a place near Yanbu], Quda’ah used to worship Wudd and they had place him in Dūmat al Jandal. An’um clan of Tai (Ṭāʾī طاءي) and Madhḥij worshiped Yaghlūth in Jurash [a place in Yemen]. Ya’ūq was idol of Khaywān clan of Hamdan (Hamdān هَمدان) and they had placed it in their own territory in Yemen. Dhu ’l Kalā’ Clan of Ḥimyar worshipped Nasr located in their own territory. Khaulān tribe had ‘Ammanas in their territory. Milkān clan of Kinanah reverenced a rock by name of Sa’d located in their desert plane [near Jidda according to other sources]. Dhu l Khalṣa, located in Tabāla, belonged to Daus, Khath’am and Bajīla. Fals was the idol of Tai located in their own territory. Dhu ’l Ka’bāt was the idol of Bakr bin Wāʾil and Taghlib located at Sindād, recognized as a place south of present-day Kufa. 32 By looking at the geographic locations of the above-mentioned idols we can authenticate the hypothesis that polytheism was practiced all over Arabia. Despite the presence of Christians and Jews, the predominant religion in Yemen and Hadarmaut was polytheism. There were shrines on the pattern of Mecca where the pilgrimage took place. 33

Pagans of Mecca

For obvious reasons historians are more interested in Pagan beliefs and practices prevalent in pre-Islamic Mecca and this topic is studied in more detail than pagan practices elsewhere in Arabia.

Waqidi tells us that there was not a single man in Mecca who did not have an idol in his home. Whenever a man entered or left the house he touched the idol to get a blessing.34 Kalbi confirms it saying that every family in Mecca had an idol at home which they worshiped. Whenever one of them purposed to set out on a journey his last act before leaving the house would be to touch the idol in hope of an auspicious journey; and on his return, the first thing he would do was to touch it again in gratitude for a propitious return.35 Ibn Ishaq reports that there were three hundred and sixty ansāb in Mecca.36

Three idols were of special importance to the Quraysh, none of them was in Mecca. Out of the three sacred idols, Ibn al-Kalbi reports that al-‘Uzza was more recent than Allāt or Manāh. Her idol was situated in a valley in Nakhlat al-Sha’miyah called Hurad alongside Ghumayr to the right of the road from Mecca to Iraq, above Dhat-Irq and nine miles from Bustin. A house was built over it called Buss. People used to receive sermons in it. Arabs and Quraysh venerated her and Quraysh used to travel to her, offering her gifts and sacrifices. 37 It was customary to divide the meat of sacrifice among those who offered it and among those who were present at the ceremony. Quraysh offered al-‘Uzza more than what they offered to any other idol. Other tribes who venerated ‘Uzza were Ghani and Bahilah.38 While circumambulating the ka’ba Quraysh used to say: ‘by Allāt and al-‘Uzza; and Manāh, the third idol besides; verily they are the most exalted females; whose intercession is to be sought. Banu Shayban of Banu Sulaym were custodians of al-‘Uzza. In the year of Fath Mecca the Prophet sent Kahlid bin Walid who killed Dubayyah bin Harami al Sulaymi, the custodian of al-‘Uzza.39

According to Ibn al kalbi Allāt used to stand in Taif. It was more recent than Manāh. It was a square rock [cubic]. Her custody was in the hands of the Banu ‘Attab bin Malik of the Thaqīf, who had built an edifice over her. The Quraysh and all other Arabs used to venerate her. The apostle of Islam sent Mughirāh bin Shu’bab who destroyed her and burnt her [temple] to the ground. In this connection Shaddid bin ‘Arid al-Jushami’ said: ‘come not to Allāt, for Allah hath doomed her to destruction; how can you stand by one which doth not triumph?; verily that which, when set on fire, resisted not the flames; Nor saved her stones, is inglorious and worthless; hence when the apostle in your place shall arrive; and then leave, not one of her votaries shall be left.40

Manāh, in Ibn al Kalbi’s account, was erected on the seashore in the vicinity of Mushallal in Qudayd between Medina and Mecca. All Arabs venerated her, particularly Aws and Khazraj, as well as inhabitants of Medina and Mecca. They sacrificed before her and brought offerings to her. Ma’add, Rabi’ah, and Mudar also venerated here but not as much as Aws and Khazraj. Aws and Khazraj as well as Arabs among the people of Yathrib used to perform pilgrimage [to Ka’ba], observed vigil at all appointed points, but did not shave their heads, instead, they went to the place where Manāh was erected and shaved their heads there and stayed there for a while. In 8 AH, Prophet sent Ali to destroy it, who destroyed it and brought a treasure back that was offered to her. It contained two swords which had been presented to (Manāh) by Ḥārith bin abi-Shamir al-Ghassāni, the king of Ghassān. One sword was called Mikhdam and the other Rasub. The prophet gave them to ‘Ali. One of them was hence called Dhu ‘l Faqār (ذوالفقار). It is also said that ‘Ali found these swords in [the temple of] al-Fals were idle for the Ṭāʾī was located and which he destroyed.41

Ibn al Kalbi believes that Aws and Khazraj venerated Manāh more, Thaqīf venerated Allāt more and Quraysh venerated ‘Uzza more because they were located near them. They did not venerate Wadd, Suwa’, Yaghuth, Ya’us and Nasr as they were located far.42 These five are also mentioned in the Qur’an.43

Ibn al Kalbi reports that Quraysh had another idol by name of Manaf (Manāf مَناف). He does not know where it stood. Menstruating women were not allowed to come near him or to touch him.44

Ibn al kalbi mentions that Isaf (Isāf اِساف) and Na’ilah (Nā’ilah نَاءِلَه) were a couple.45 Isaf stood near the ka’ba while Na’ilah was placed by Zamzam. Later on Quraysh moved Isaf to the side of Na’ilah and sacrificed to both.46 Waqidi tells us that Isaf and Na’ilah stood at the place of slaughter and sacrifice of the sacrificial animals.47 According to Ibn Ishaq both were near Zamzam.48

According to Waqidi there were three hundred idols around Ka’ba. Hubal (هُبَل) was the largest of them. It faced towards the Ka’ba at its door.49 Ibn al Kalbi confirms that the biggest idol around Ka’ba was Hubal. He gives details that it was made from red agate, in the form of man. Hubal had its right hand broken off. When it came into Quraysh’s possession they made a hand of gold for him. According to Ibn al Kalbi it stood inside the Ka’ba. In front of it were seven divination arrows (sing. qidh, pil. qidhah or aqdhuh). On one of these arrows was written ‘pure’ (ṣarīh), and on another ‘consociated alien’ (mulsag). Whenever the lineage of a newborn was doubted, they would offer a sacrifice to Hubal and then shuffle the arrows and throw them. If the arrow showed the word ‘pure’ the child would be declared legitimate and the tribe would accept him. If, however, the arrows showed the word ‘consociated alien’ the child would be declared illegitimate and the tribe would reject him. The third arrow was for divination concerning the dead, while the fourth was for divination concerning marriage. Ibn al Kalbi doesn’t explain the purpose of the three other arrows. Whenever they disagreed concerning something or purposed to embark upon a journey or undertake some project, they would proceed to Hubal and shuffle the divination arrows before it. Whatever result they obtained they would follow and do accordingly. ‘Abd ul Muṭṭalib shuffled arrows here to choose which of his sons should be sacrificed.50

Hubal was a deity associated with the Ka’ba. He was the one and only statue situated inside Ka’ba. Ibn Ishaq reports that when Arabs wanted to circumcise a boy or marry someone, or burry a body, or when they doubted someone’s descent, they would take the person to Hubal with a hundred dirhams and a sacrificial animal and would cast the arrows of Hubal and thus know what their conduct should be.51 The rituals like circumcision appear to be Ibrahimic.52

Belief in Allah

Did pre-Islamic Arabs believe in Allah? The answer is yes! The very name of Prophet Muhammad’s father, ‘Abd Allah, provides ample proof. Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry is saturated with the name ‘Allah’. For example, pre-Islamic verse of Nabigha: I took an oath and left no margin of the doubt for who else can support man, besides Allah.53 A couplet of pre-Islamic poet Imru’ ‘l Qays: She said (to her lover), “I swear by Allah that you have no way of attaining what you desire; even if I see allurement appear from you.” (Faqaalat, “yamainallaha malik hylata; wa ma in ari ankalghawayyeyah tanjli”.54 Even Abu Jahl is reported by Ibn Ishaq to have uttered about his fellow polytheists on one occasion, “You lie! By Allah.”55 The Qurʾan verifies pre-Islamic Arab’s belief in Allah, “If you ask them, “who created the heavens and earth, and subjected the sun and the moon?” they would surely say, “Allah.” . . . . and if you ask them, “Who sends down rain from the sky and gives life thereby to the earth after its lifelessness?” they would surely say “Allah.”. .. . and when they board a ship, they supplicate Allah, sincere to Him in religion. But when He delivers them to the land, at once they associate (yushrikūn) others with Him.56

Zabad inscription: writing beneath is the transcription of Arabic.

Meccan polytheists began their formal writings with the name of Allah. The only portion of the scroll on which the boycotting agreement was written by the Quraysh polytheists, that was not eaten by worms contained this formula: ‘In thy name O Allah’ (bi ism Allah).57 At the time of writing the peace treaty of Ḥudaybiyah Suhayl, the representative of Meccan polytheists, insisted on writing ‘Allahumma’ (in the name of Allah) as the Quraysh used to write on top of contracts.58 Interestingly, they used to exclaim ‘Allah Akbar’ on joyous occasions. This is what ‘Abd ul Muṭṭalib shouted on discovering Zamzam.59

It would be interesting to note that the Zabad inscription, found to the south of Aleppo (Ḥalab حلب) and first described by Sachau, mentions God by name of Al-llah. This famous inscription was written on a door lentil in 512 CE.60 Another dated inscription, written after Zabad inscription in 548 CE and found in Jawf near Dūmat al Jandal, Saudi Arabia also mentions God by name of Al-Ilah.61 Similarly, a Nabatean inscription found at Rawwafah, Saudi Arabia mentions `lh as god.62 We don’t know exactly how far and wide was Allah believed in but here one tradition recorded by Ibn Ishaq about pre-Islamic Arabs will be interesting. He informs us that Khaulan country had an Idol ‘Ammanas’. They used to divide their crops and cattle between it and Allah.63 The belief in Allah had some penetration among monotheists. Ibn Ishaq mentions a Jew by name of Abdullah bin Ṣūriyā from Banu Tha’laba who never converted to Islam and was the most learned man in Torah studies.64 Similarly, the name of a Christian who came to Medina with the deputation from Najran to argue with the Prophet was Abdullah.65

If pre-Islamic pagans believed in Allah, why did they not have an idol of Allah? The answer is clear. In one tradition the Prophet asked Ḥasīn bin ‘Ubaid of Banu Khuza’ah, who was sent by them to reason with the Prophet, “How many gods do you worship?” He said ‘seven on earth and one in heaven.’66 This “god of heaven” comes to be known from the chief of the tribe Muzaynah (مُزينه) who broke the idol Nahum and declared in his verse that he henceforth worshiped the “Allah of heaven.”67 A Thaqīf (who used to live near Taif) converted to Islam and asked Prophet Muhammad whether he should keep a vow made before conversion. Questioning elicited that he had made a vow to Allah and not to any idol. The Prophet declared that he should keep.68 So, the Quraysh did not have any idol of Allah because according to their belief He was God of the heavens.

The question arises: what was the relation between Allah and other numerous gods in their belief system? Wellhausen points out that as there was no idol for Allah and Allah was their high god, other pre-Islamic deities were inferior to Allah in status. Pagan Arabs believed that they will do intercession with Allah for them.69 It is verified by the Qur’an, “When Allah was called alone, you disbelieved, but if others were associated with Him (inn yushrak bi-hi), you believed’.70 Other Qur’anic verses speak as well of the pagan deities acting as intermediaries between men and Allah, and in particular interceding with Allah on behalf of men. “And those who take protectors besides Him (say), “We only worship them that they may bring us nearer to Allah in position.”71 At another place the Qur’an says of the pagans, “And they worship other than Allah which neither harms them nor benefits them, and they say, “These are our intercessors (shufa‘a) with Allah.”72 In another Qur’anic verse about pagans, “And the Day the Hour appears the criminals will be in despair. And there will not be for them among their partners (shurakā) any intercessors (shufa’a), and they will be disbelievers in their partners.73 Pagan Arabs believed that lesser gods could affect their lives negatively if annoyed. Ḍimām bin Tha’laba, a representative of Sa’d bin Bakr accepted Islam in 630 CE. Then he went back to his people and asked them ‘how evil are al-Lāt and al-‘Uzza.?’ They said ‘Heavens above! Beware of leprosy and elephantiasis and madness’. He said ‘Woe to you, they can neither hurt nor heal’.74

Pilgrimage to the Ka’ba

Pre-Islamic Arabs used to pilgrim the Ka’ba. Ibn al Kalbi, while describing their rituals, mentions, “They did the pilgrimage, the visitation or the lesser (al-‘Umrah), the vigil (al-Wuqul) on ‘Arafah and Muzdalifah, sacrificing she-camels and raising acclamation of the name of the deity (tahlil) [these days tahlil is la illaha illallah] age and the visitation, introducing there into belonging to it. Thus however the Nizar [the main group of north Arabians] raised their voice the tahlil they were wont to say “: labbayka allahumma labbayka; lak illa sharikun husa lak tamlikuhuu wa; ma malak. (In English; here we are O Allah! Here we are; Thou hast no associate save one who is thine; Thou hast domination over him and over what he possesseth). They would thus declare His unity through the talbiyah and at the same tune associate their gods with Him placing their affairs in His hands. Consequently, Allah said to His prophet, ‘and most of them believe not in associating other deities with Him [Qur’an 12:106]’. In other words, they would not declare His unity through the knowledge of His rightful dues, without associating with Him some of His own creatures.75 Though the language of this passage translated in English by Faris is not very clear, it points out many important beliefs and practices of pagan Arabs. First, they believed in gods who shared some properties of Allah. Second, they performed both hajj and ‘umrah to ka’ba. Third, they used to vigil in ‘Arafah and Muzdalifah. Fourth, they came to pilgrimage chanting talabiyah. Fifth, they sacrificed animals during their pilgrimage chanting tahlil for their gods. Talbiya is the only prayer of pre-Islamic pagans that has been preserved.76 Ibn Ishaq mentions the ceremony of throwing stones at Mina during pilgrimage rituals of pagan Arabs.77 Quraysh used to call Ka’ba their mosque (masjid).78

Currently, hajj is performed in an area of roughly five kilometres in width and thirty kilometres in length around the Ka’ba, called Ḥaram. Muslims put up iḥrām (ritual consecration اِحرام) before entering the Ḥaram. Any act of violence or sex is forbidden inside Ḥaram. They enter the Ḥaram chanting Talbiyah (تَلبِيَه). After entering the Ḥaram they proceed to Mina, which is located about eight kilometres east of the Ka’ba. Rituals start at Mina on the 8th Dhu ‘l Hajjah, where Muslims spend the night in sunnah of the Prophet. On the morning of 9th Dhu ‘l Hajjah they arrive on the plains of ‘Arafat about twenty-two kilometres further southeast of Mina. They stand there the whole day praying, facing toward the Ka’ba. Nearby Jabl al Rahmat (mount of mercy) is said to be the place where the Prophet gave his last sermon. After sunset, the pilgrims go to and stay at Muzdalifah in between ‘Arafat and Mina where they worship more and take a rest. The next day morning, before leaving Muzdalifah, they pick stones. Then they move to Mina, where on 10th Dhu ‘l Hajjah they throw stones to Jamrat al Aqabah, the three pillars. Afterwards, they sacrifice animals. Then pilgrims take off ihram. Men shave their heads and women cut off a symbolic lock. Everybody takes a bath and puts on new clothes. Before performing ṭawāf (circumambulation طواف) each pilgrim again throws stones on Jamrat ul Aqabah. Ṭawaf should be performed before sunset of 12th Dhu ‘l Hajjah. Each circumambulation starts from the Black Stone. They are a total of seven and be performed while reciting prayers. Pilgrims kiss Black Stone while doing ṭawaf. Then they run seven times between Ṣafa and Marwa. As the last ritual, they drink water from Zamzam.79

Detailed scrutiny of early Islamic sources confirms that different tribes attending the pilgrimage of the ka’ba in pre-Islamic times were free to perform rituals the way they believed to be correct. For example, Ibn al Kalbi reports that Rahia [North Arabian tribe] performed the pilgrimage, observed sacred rites and ceremonies, and carried out vigils at the appointed places, they then started back with the first group and did not wait until al-tashrīq [days next after the days of sacrifice on the 10th].80 However, two important grouping of tribes on the basis of the way rituals were performed were Hilla and Hums. Their difference in how rituals should be performed spanned from the time of putting up ihram to ṭawaf. It does not mean both had entirely different religious beliefs. Hilla had to take a different route from that of Hums after entering into the boundaries of the Haram. They were taxed and were not allowed to bring their supplies into Haram. Quraysh charged them for food and water that was provided by the Quraysh. It appears that part of Hilla did not perform rituals at all. Early resources, while defining Muhrimun tell that they consisted of Hums and those tribes of Hilla who performed the pilgrimage rituals. It means those Hilla who did not perform pilgrimage were called Mubillun.81 The Hums observed certain precepts of avoidance in their cultic practices during the consecrated state of ihram in the holy months; they did not prepare any curds or butter, they did not eat any clarified butter (ṣaman صمن), they practised sexual abstinence, wore clothes only made of camel hair and did not use these as protection against the sun; they avoided tents made out of goat’s hair; they did not seek out any shade; during the ihram state, they did not enter homes through the house door, but through the specially made opening at the rear of the house; they shunned the meat of game and marriages with Hilla (non-members of Hums).82 The Quraysh associated themselves with Hums. The religious brotherhood of the Quraysh and the Hums was something of pride for them. Zubayr bin ‘Abd ul Muṭṭalib bin Hāshim bin ‘Abd Manāf says in a poem: ‘If there were not any Hums, men would not be able to don a gown of honour their whole life long.83 At the ceremonies of Muzdalifah the Quraysh and their co-religionists Hums used to say, “we are the family of Allah”.84 Noteworthy is that Quraysh and their co-religionists did not attend rituals at Arafah.85

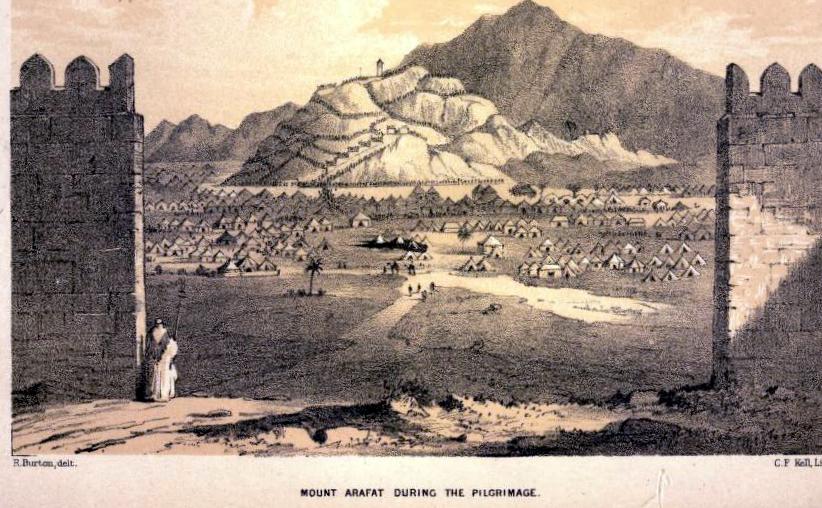

Sketch of Mount Arafat by Richard F. Burton. 1853 CE86

A stone of special reverence present in the vicinity of the Ka’ba was the Black Stone (Ḥajr al Aswad حَجْر الاَسْوَد). Mujahid (d. 722 CE) explained as recorded by Fakihi, the stone became black as the Quraysh used to stain it with blood.99 Another report of Fakihi tells us that the Quraysh used to stain it with intestines (farth) when they slaughtered.100 Ibn Ishaq reports that there was an ancient inscription on the Black Stone, considered by the Quraysh to be in Syrian, and deciphered for them by a Jew.101 The mountain of Abu Qubays (whose foothill was Ṣafa) was revered by Arabs on its own. For example, Baladhuri notes that the people of Quraysh headed by ‘Abd ul Muṭṭalib climbed up Abu Qubays to pray for rain and they were answered immediately.102 It is reported that the Quraysh brought stones from far-off places to build the Ka’ba including Abu Qubays.103 Actually the Black Stone was moved to the vicinity of Ka’ba from Abu Qubays. Shifting of Black Stone from Abu Qubays could be a motivational attempt to divert worshipers to the Ka’ba. The eastern corner of the Ka’ba, where Black Stone was originally placed, was nearer to Abu Qubays. This was the stone by touching of which they started tawaf of Ka’ba similar to the touching of Isaf and Na’ilah by Hilla while doing tawaf of Ṣafa and Marwa.104

The pilgrimage had some rituals related to clothes. According to Azraqi pilgrims used to cast their sacred clothes between Isaf and Na’ilah at the end of the tawaf around Ka’ba. These clothes became laqan, i.e. were put under taboo, and no one was allowed to touch or to use them and they remained there till they fell apart.105

Drinking water during pilgrimage was not for quenching thirst. It had a religious connotation. Quraysh associated Zamzam with Ibrāhīm (the same personality who is called Abraham in Christian and Jewish traditions and who is considered the patriarch of all Middle Eastern monotheist religions). A report by Ibn Ishaq verifies this belief of the Quraysh. When ‘Abd ul Muṭṭalib discovered Zamzam, Quraysh disputed its ownership saying that “this is the well of our father Isma’il.”106

They used to offer valuables to their deities. Azraqi reports that the people used to cast the votive gifts between Isaf and Na’ilah which were donated to the Ka’ba.107 Ma’mar reports that ‘Abd ul Muṭṭalib found a sword when digging zamzam.108 Fakihi reports on the reference to ‘Ikrima (d. 723 CE) that ‘Abd ul Muṭṭalib discovered a treasure while digging Zamzam. It contained a golden image of a gazelle (ghazal غزل) decorated with a pair of earrings, as well as jewellery of gold and silver, and some swords wrapped up in garments. ‘Abd ul Muṭṭalib’s fellow tribesmen demanded a share in the treasure, and therefor he cast a lot by arrows according to which the jewellery had to be donated to the Ka’ba, the swords had to be granted to ‘Abd ul Muṭṭalib and the gazelle to the Quraysh.109 Apparently tradition of casting gifts and burying them near Zamzam continued. As we know from other ancient cultures, burying gifts is a reverence to the dead, it can be postulated that casting gifts at Zamzam was a reverence to those who were buried there.110 In addition to Zamzam, gifts were also cast to a pit (khizāna خزانه) located inside Ka’ba according to Azraqi.111

The pilgrimage took place during the months of the truce. For the same reason, all pilgrimages of the pre-Islamic era had fairs attached to them. Bedouins could market themselves, entertain themselves and shine at these fairs. Truce months were the last two months of a year and the first month of the next year, all of which came in the fall according to the intercalated calendar of Arabs. Rajab was another month of truce in the spring when ‘umra took place.112 In the words of Tawhidi “then they (the Arabs) would journey to ‘Ukaz and Dhu ‘l Majaz in the holy months and would hold their markets in them. They would stage poetry competitions and debating contests and settle their differences. Whoever had a lawsuit would submit it to the member of Tamim who was in charge of legal affairs. Then they would stop at ‘Arafa and perform the required rites, and after that they would head for their homelands.113

Reverence of Ka’ba had diffused into followers of other religions as well. For example, ‘Abdallah bin Salam, a prominent Jew of Medina from Banu Qaynuqā’, who later embraced Islam, once talking to Jews of Medina before conversion, expressed his wish to visit Ka’ba as the house of Ibrahim.114 Quraysh and Jews took an oath with a curtain of the Ka’ba to be together in the battle of Khandaq.115 However, most of the Jews did not reverence Ka’ba. For example, when Prophet Muhammad diverted his qibla from Jerusalem to Mecca, the leaders of Jews at Yathrib told him that if he claimed to be adherent of din Ibrahim, he must return to the former qibla.116 Some Christians also venerated Ka’ba and prayed facing it.117

As Ka’ba and its vicinity were sacred to the pagan Arabs and others, it is not surprising that the premises were used to make solemn promises. According to ‘Adawi, Hatim was a place where pre-Islamic Arabs used to practice qasama (a collective, compurgative oath قسمه). 118 Azraqi explained that each imprecation uttered in the Hatim against an evil-doer only seldom escaped an immediate punishment. Whoever took a false oath in that place could not avoid an instant penalty. This held people back from sins, and they were afraid of taking false oaths in the Hatim.119 Apparently tradition of making solemn promises in Hatim continued during early Islamic period and is suggested from the tradition that ibn Muljam vowed in Hatim to execute ‘Ali bin Abu Ṭālib.120

Some religious beliefs in Mecca and elsewhere

Pagan Arabs believed in prophets (رسل rusul). The Interior of the ka’ba was decorated with many pictures of prophets.121 At the time of the conquest of Mecca the Prophet asked to erase all of them except those of Jesus and Mary which were allowed to be kept.122 Out of all prophets, Arab’s belief in Ibrahim and his son Isma’il is the most documented. Wellhausen has established that circumcision was common among pre-Islamic Arabs.123 This tradition of circumcision and its link with Ibrahim in Arabia is witnessed by Josephus Flavius, a first-century CE Jew scholar from Jerusalem, who writes that the Arabs circumcise after the thirteenth year, because Isma’il, the founder of their nation, who was born to Ibrahim of the concubine, was circumcised at that age.124, [Actually pagan Arabs took pride in the tradition of circumcision, which distinguished them from the Christians who did not practice it. One incident noted by Waqidi clarifies it: when the Muslim side came across a dead body of a Thaqif during Hunain that was uncircumcised, they shouted with disgust that the Thaqīf didn’t circumcise themselves. Thaqīf corrected promptly that this was a body of a Christian Thaqīf. 125

The ritual of casting arrows in front of Hubal was in itself Ibrahimic. They had painted an image of Ibrahim holding these arrows inside Ka’ba and when Mecca was conquered, Prophet Muhammad ordered it to be erased, according to Waqidi.126 Tabari reports that an ancient, dried-up pair of horns of the ram (kabsh) was hung on the spout of Ka’ba allegedly by Ibrahim until the days of Abdullah bin Zubayr when they disintegrated. 127 Motive of Ibrahim’s offering his son for sacrifice was well known to the pre-Islamic Arabs. It is dealt with in verses of the non-Muslim poet, Umayya bin Abi l-Salat, recorded by Tabri123 and is independent of the Qur’an.128 A verse attributed to Abu Ṭālib by Ibn Ishaq, “By Ibrahim’s footprint in the rock still fresh/with both feet bare, without sandals” not only establishes pre-Islamic belief in the prophethood of Ibrahim but also that Maqām was there before Prophet Muhammad.129 Actually, Meccans believed that it was Ibrahim himself who created the Ḥaram of Mecca. Mohammad bin Habīb (d. 859 CE) records a story in Munamaq that the Quraysh once asked Thaqif to become their partners in the Meccan Haram in return for equal partnership of Quraysh in the territory of Wajj which was owned by Thaqif. The Thaqif refused saying ‘how can you be partners in a land in which our father settled, and dug it out of the rocks with his bare hands, without iron tools. And you have not founded the Haram by yourselves; it was Ibrāhīm who founded it’.130 One verse attributed to ‘Abd ul Muṭṭalib by Ya’qubi again reiterates pre-Islamic Arab’s belief in the prophethood of Ibrahim, ‘we are the people of Allah in His town/ this has always been according to Ibrāhīm’s covenant’.131

One interesting prophet they believed in was Shu’ayb (شُعَيب). Shu’ayb is not mentioned in the Bible and is a Qur’anic personality,128 who was sent to Madyan and Ayka to ask people to respect justice and equity and refrain from falsifying weights and measures.132 According to the tradition he was from Banu Judham from the clan of Banu Wāʾil. Prophet Muhammad greeted the delegate of Judham saying ‘welcome to the people of Shu’ayb!” According to Muslim traditions, Shu’ayb is the father-in-law of Moses. Maqrizie describes Madyan as being located on Bahr Qulzum [Red Sea], at a distance of six marāhil from Tabūk.133

They believed that many prophets were buried around Ka’ba. Tabari in Tarikh notes that Adam, Eve and Sheth are buried at the mountain of Abu Qubays in a cave.134 Ibn Ishaq informs us that Isma’il and Hajrah are buried in Hijr.135 Azraqi reports a tradition of Muqatil that seventy prophets, including Hud, Saleh and Ismail, were buried between Zamzam and the Rukn.136 This kind of tradition also gives a hint of reverence that they felt for the dead.137

Quraysh used to believe in angles and they had made their images on the interior of the Ka’ba.138 Ibn Ishaq notes that to deny Prophet Muhammad’s concept of angels some Quraysh reiterated that they believed in angels as daughters of Allah.139 Ibn Ishaq also reports on the tradition of ‘Abdullah bin Ziba’rā, a Meccan polytheist, that the Quraysh used to worship angels.140

Pagans of Mecca used to offer ritual prayer (ṣalāt صلۈة). The exact nature of their prayer is not known. The Qur’an gives only a glimpse that the prayer of pagans involved clapping and whistling.141 Apparently, prayer does not seem to have been very important in the practice of pre-Islamic cults. Sacrifices, bloody as well as those that did not involve the shedding of blood, are more frequently mentioned. Sacrificed animals were camel, sheep and ox. Fowl are never mentioned.142 Libation of milk, wine and oil are other sacrifices.143 Muqatil bin Sulayman has reported that when pre-Islamic Arabs slaughtered their sacrificial animal, blood was sprinkled upon idols as well as upon walls of the Ka’ba.144 Henninger sees a similarity between the current practice of pouring and sprinkling blood and keeping bones of sacrificed animals intact among some Northern Asian stock farmers and the custom of sprinkling blood in pagan Arabs. Northern Asians believe if bones are kept intact and an animal is killed by letting blood, the sacrificed animal can regenerate.145 Tabari reports that sacrificial meat was sliced and also laid upon sacred stones. Some meat was cooked and eaten by the worshippers in a communion feast as reported by Bayhaqi.146 Human hair has been mentioned in sacrificial rituals. However, according to Henninger, the offering of human hair was not a true sacrifice but a rite of passage, involving a transition from the profane to sacred or in the reverse direction.147

The practice of human sacrifice as a religious ritual among pre-Islamic Arab Pagans is debatable. It is known that king Mundhir of Hirah sacrificed four hundred virgins to the goddess al-‘Uzza in 527 CE.148 The same king Mundhir also sacrificed a son of Ḥārith, the king of Ghassaan to al-‘Uzza.149 As victims were prisoners of war in both cases, it is plausible that it represented the victory-giving deity’s share in the booty. However, it is not logical to generalize human sacrifice to pre-Islamic Arabs on basis of the acts of one tyrant king. Ibn Ishaq’s story that once ‘Abd ul Muṭṭalib intended to slaughter his son ‘Abd Allah, between Isaf and Na’ilah for Allah, gives a hint that human sacrifice was thinkable.150 But the way Quraysh responded to his intention, in the same tradition of Ibn Ishaq, by advising him against this act with the argument that it would make a bad precedent, establishes that human sacrifice was actually not practiced in Mecca.

Meccans used to practice a rite called taḥannuth (تَحَنُّث)in the month of Ramadan (Ramaḍān رَمَضان). The exact meaning of this rite is not known.151 A hint of what it could be comes from a tradition narrated by ‘Ubayd bin ‘Umayr bin Qatāda and preserved by Ibn Ishaq. The tradition goes that ‘the Apostle would pray in seclusion in Ḥirāʾ (حراء) every year for a month to practice taḥannuth, as was the custom of Quraysh. Taḥannuth appears to be religious devotion. Praising people who practiced taḥannuth, Abū Ṭālib said: By Thaur and him who made Thabīr firm in its place; And by those going up to ascend Ḥirāʾ and coming down’. 152

Meccans also had a concept of some kind of day of judgment. It is evident from a pre-Islamic verse by Zuhair bin Abi Salma: ‘the deeds are recorded in the scroll to be presented on; the day of judgement; vengeance can be taken in this world too’.153 Similar themes are expressed in verses attributed to Zayd bin ‘Amr by Ibn Ishaq that are allegedly pre-Islamic.

I serve my Lord the compassionate

That the forgiving Lord may pardon my sin,

So keep to the fear of Allah your Lord;

While you hold to that you will not perish.

You will see the pious living in gardens,

While for the infidels (kāfir) hell fire is burning

Shamed in life, when they die

Their breasts will contract in anguish. 154

Ibn Ishaq reports an intriguing story where some people of Thaqif were afraid of shooting stars. They asked ‘Amr bin Umayya of banu ‘Ilāj about it. He said if they are the well-known stars which guide travellers by land and sea, by which the seasons of summer and winter are known to help men in their daily life, which are being thrown, then by Allah! It means the end of the world and the destruction of all that is in it. But if they remain constant and other stars are being thrown, then it is for some purpose that Allah intends towards mankind.155 As it is a pre-Islamic story, worth noting that is the ‘end of the world’.

Gibb argues that words expressing religious themes in the Qur’an, at least in the earliest verses, must have been used among Meccans before Islam. Otherwise, the Quraysh would not have been able to even understand them. Words like tanzīl, waḥī, etc. would have been well understood.156

One interesting belief of pagan Meccans was in ‘true dreams’ as Devine guidance if someone purposely slept in Hijr (Hatim). Baladhuri reports in Ansab that Kinānah heard a voice while sleeping in Hijr, telling him about his future.157 In a similar report Khargushi says that Nadr bin Kinānah dreamt in the same place that a cosmic luminous tree was emerging from his loins which symbolized his noble descendants, and especially Prophet Muhammad.158 Ibn Ishaq and Ma’mar report that Abd ul- Muṭṭalib was inspired by a series of dreams while asleep in Hijr to dig Zamzam.159 ʾĀmnah, Prophet Muhammad’s mother, dreamt in the Hijr that she was about to give birth to ‘Ahmad’, the lord of mankind according to ibn Habīb in Munammaq.160 These traditions give a clue that sleeping in Hijr was used to get Devine inspiration through dreams.161

One noteworthy pre-Islamic belief is the concept of Satan (sheyṭān شَيطان). When a polytheist Juhaym bin Ṣalt dreamt before the battle of Badr that many of the leaders of Quraysh would be slain, the Quraysh polytheists said to Juhaym, “Surely Satan jokes with you in your sleep”.162

Another noteworthy belief of pre-Islamic pagans was in Jinn (جن). Ibn Ishaq reports that Quraysh used to ‘take refuge in the lord of Valley of Jinn from the evil’.163 On another occasion, where Ibn Ishaq is reporting Quraysh’s arguments with Prophet Muhammad, they use the word Jinn in sense of a spirit that can possess a person temporarily.164 Banu Mulayh of Khuza’ah are said to worship the jinn.165 Pre-Islamic Arabs also believed in Qarīn (قارين) who was a jinn pairing humans, born with them and died with them.166 Wellhausen considers jinn as a spirit that was universal as opposed to personified gods.167 Albright has demonstrated that Bedouin belief in jinn had started only in the late pre-Islamic period.168 An inscription from the environs of Palmyra says; ‘the jinnaye of the village of Beth Fase’el, the good and rewarding gods’.169 The word ‘jinn’ could have originated like that.

Early Muslim scholars also mention ghouls (ghul غول) which ‘manifest themselves in different forms to people in desolate places’, particularly at night and try to lead them off their course.170 Their natural appearance is very ugly: ‘two eyes in a hideous head like that of a split tongued cat, with a cleft tongue; two legs with cloven hooves and the scalp of a dog’.171 Because its feet are like those of an ass, ‘when it presents itself to the Arabs in the wastelands they utter the following couplet: ‘oh ass footed one, just bray away; we won’t leave the desert plain nor ever go astray’ …. And it will then flee from them into valley bottoms and mountaintops’.172

Arab’s belief in magic is evident from a very ancient Safaitic text which tells us that a certain Sharab bin Ahbad had a period of derangement due to the magic spell (‘wdht rqwt).173 Another piece of evidence comes from a tradition that Prophet Muhammad was cast magic by Labīd bin ‘Āṣim.174 They used amulets to counter magic as is evident from this pre-Islamic verse: ‘A warrior would make sure that his steed was ‘shielded by spells (ruqa) so that she (horse) takes no hurt and amulets (tama’im) are tied to her neck-gear.’ 175

Level of religiosity among Bedouins

When Imru’ l Qays bin Hujr set out to raid Banu Asad he passed by Dhu ‘l Khalṣa (an idol that stood at Tabāla somewhere between Mecca and Sana’a a seven nights journey from Mecca). He cast Divination arrows three times and three times he drew the arrow ‘forbidden’. He broke arrows and hurled them at the idol exclaiming ‘go bite thy father’s penis! Had it been thy father who was murdered, thou wouldst not have forbidden me avenging him. He then raided Asad and defeated them.176 This pre-Islamic story, cited by Ibn al kalbi, is quoted by some scholars as proof that Bedouins were indifferent to religion. This theory is not entirely without justification. We know that they were not zealous even in practicing Islam after its advent and that Islam was mainly urban in character. Bedouin’s moral ideal of murūʾah (virility) had no religious character. However, to conclude that Bedouin population of pre-Islamic Arabs had a total absence of religious sentiments is going too far. The lack of mention of the religious affairs of Bedouins in pre-Islamic poetry is not ample proof of their indifference to religion. The subject matter of pre-Islamic poetry was narrow and as a such absence of religious themes in it does not prove beyond doubt that Bedouins were not interested in religion.177

Secondary forms of monotheism

A startling discovery by archaeologists and historians is the existence of belief in a monotheistic God in some parts of Arabia that was neither God of Christians nor of Jews. Madain Saleh, Saudi Arabia has produced a dated inscription from 267 CE in early Arabic script mentioning the ‘lord of the world’ (Rabb ul ‘Ālam) as single god.178 Of particular interest is the word Reḥmān that is used in South Arabian inscriptions to describe god. This god is further characterized as ‘lord of Heaven’ and ‘lord of heaven and earth’. Robin, who has studied all Yemeni religious inscriptions of the fourth and fifth centuries, points out that there is a monotheistic content in these inscriptions due to belief in a unique god ‘Rehman’.179 Robin believes that ‘Rehman’ and his characteristics would have developed under Jewish influence as nobility in South Arabia was Jewish. In Askar’s opinion, the definition of Rehman in pre-Islamic inscriptions is exactly similar to its use during Islamic times.180 This god ‘Rehman’ can be traced as far back in Himyarite inscriptions as 448 CE.181 The same word ‘Rehman’ is used by A’sha in pre-Islamic poetry and in the same context.182 There were two individuals contemporary to Prophet Muhammad who called themselves Rehman. One was Musaylima of Yamama and the other was Aswad al-‘Anasi of Yemen.183 Meccan pagans were aware of ‘Rehman’ though they did not believe in him. Musaylima was also known to them. In Ibn Ishaq’s tradition, Quraysh declined the call of Prophet Muhammad to believe in ‘Al-Rehman’, ‘the compassionate’. They responded antagonistically saying; ‘indeed we have known a man from al-Yamama called Rehman, and therefore, we will never believe in him.184 It appears that this confusion among Meccan pagans whether Rehman is the name of God or a person continued. In his commentary, Tabri mentions that Allah is also ‘al-Reḥmān’, but once people started to use ‘al-Rehman’ as a name ‘referring to Musaylima’, Allah almighty added the word ‘al-Rahīm’.185 This might explain the circumstances surrounding the phrase ‘Bism Allah al-Raḥmān al-Rahīm’. Prophet Muhammad insisted that ‘Rehman’ is another name of Allah as is ‘Rahim’. His companion ‘Abd ‘Amr bin ‘Auf changed his name to ‘Abd ur Raḥmān bin ‘Auf to witness that Allah and Rahman are the same. However, we do not find anybody named to be ‘Abd Rahīm’ in Prophet’s time.186

Hanif

Lastly, mention is necessary of a unique group of intellectuals among pagans who called themselves Ḥanif (حَنِيف sin. Ḥanīf, pl. Ḥunafa). They were all monotheists but did not associate themselves with existing monotheistic religions like Christianity or Judaism. All early Islamic sources confirm their presence though they are not mentioned as an organized religious group. Probably they were rather individualistic, similar to civil society of modern era.187

Sozomenos (5th century CE) who was born near Gaza and had a good knowledge of Arabs, describes Arabs as descendants of Isma’il who, due to the influence of their pagan neighbours, had corrupted the old ‘discipline’ of their ancestor, according to which the old Hebrews used to live prior to Moses. Sozomenos even knows of a certain group among the Arab descendants of Isma’il who eventually came in contact with the Hebrews and by learning from them resumed their original conduct.188 This description gives a feeling to some scholars as if he was talking about Prophet Muhammad and his followers.189 But the very fact that Sozomenos was active in fifth century CE verifies that was talking of people before Prophet Muhammad and was mentioning Ḥanifs.

Ḥanifs, though solitary and mutually contradicting, had a sense of belonging to one community. “Every religion will be declared untrue on the day of judgement before Allah except the Ḥanafiyya religion (kullu dinin yawma l-Qiyamati ‘ida l-lahi illa dina l- Ḥanīfati buru) declares Umayya bin Abi l-Salt (d. 630 CE), a pre-Islamic poet in a verse quoted by ibn Ishaq.190 We are told by Abu l-Baqa that Ma’add, Mudar, al-Ya’s and Asad bin Khuzayma among prophet’s ancestors were Ḥanīfiyya of Dīn Ibrāhīm and in this tradition Muslims are requested not to curse these persons.191 Some scholars, like Watt, think these are apologetic claims to show that Prophet Muhammad belonged to a noble monotheistic family who did not indulge in idolatry. However, we find staunch opponents of Prophet Muhammad to be Ḥanif as well. Why Muslims could have any interest in characterizing those opponents of Prophet Muhammad as Ḥanif if there was no such thing as Ḥanif in the pre-Islamic era? 192

Poetry and life sketches of some of the Ḥanifs have reached us. Poet Abu Qays bin Aslat was a leader of Aws Manāt and Aws bin Ḥāritha clans of Aws at Yathrib and was an opponent of Prophet Muhammad.193 Ibn Sa’d reported him to be Ḥanif and that he used to say ‘I adhere to the religion of Ibrāhīm and will not cease till I die’.194

He did not embrace Islam. His verses noted by Ibn Ishaq are;Lord of mankind, serious things have happened

The difficult and the simple are involved

Lord of mankind, if we have erred

Guide us to the good path

Were it not for our lord we should be Jews

And the religion of the Jews is not convenient

Were it not for our lord we should be Christians

Along with the monks on Mount Jalīl

But when we were created, we were created

Ḥanīf; our religion is from all generations.

We bring the sacrificial camels walking obediently in fetters

Covered with cloths but their shoulders bare. 195

Noteworthy is the 5th verse which suggests that Ḥanif had a sense of belonging to a distinct religion. The 6th verse suggests that Ḥanf had sacrificial rituals at Mecca which were similar to the sacrificial rituals performed at Mecca by others.196

In another verse quoted by ibn Ishaq, the same abu Qays bin Aslat, addresses Quraysh;

Rise and pray to your Lord and rub yourselves;

Against the corners of this house between the mountains.197

These verses show that the Ḥanifs revered the Ka’ba that was called ‘baytu llahi l- ḥaram’ and they regarded the Quraysh as legitimate custodians of the Ka’ba.198

Another Ḥanif, the poet Umayya bin abi l-Salt, mentioned above was from Taif. Umayya met Prophet Muhammad in Mecca before hijrah (migration هجرۃ) and was impressed by his teaching and inclined to embrace Islam. Later, battle of Badr broke out and he changed his mind.199 He even wrote qasīda for the Quraysh who had died at Badr.200 Isfahani reports that Abi l-Salt tended to consider himself a prophet and was jealous of Prophet Muhammad’s prophetic success.201

Abu ‘Amir ‘Abd ‘Amr bin Sayfi was a leader of Aws and was Ḥanif. Shortly after Prophet Muhammad’s arrival in Yathrib, Abu ‘Amir set out to Mecca with ten of his supporters, all refusing to embrace Islam.202 He took part in the battle of Uḥud from Meccan side.203 In fact, according to Ibn Ishaq, he was the first to attack Muslims along with the Aḥābīsh (black troops احابيش) of Quraysh.204 Following the expulsion of Naḍīr to Khaybar (625 CE) he again went to Mecca with some Jews and certain people of Aws, according to Waqidi, to urge the Quraysh to fight against Muslims.205 After the conquest of Mecca, he fled to Taif and after the surrender of Taif he went off to Syria where he died.206 His name is attached with building of a mosque in Yathrib by the name of Masjid al-Shiqaq or Masjid al-Dirar.207 Just before Tabūk’s raid (630 CE), Prophet Muhammad was asked to pray in this mosque but he refused. Prophet suspected hidden arms in the mosque and according to Waqidi, ordered to tear it down and burn.208 According to Ibn Ishaq this mosque was built by supporters of Abu ‘Amir who were intimated by him from Syria that he was bringing Byzantine troops who would oust Prophet Muhammad and his followers from Yathrib.209 Baladhuri reports that he wished to present himself as prophet.210 Ibn Ishaq reports that Abu ‘Amir came to Prophet Muhammad when the latter arrived in Yathrib, and asked him what the religion he had brought was? Prophet Muhammad said, ‘I have brought Ḥanīfiyya, the dīn of Ibrāhīm’. Abu ‘Amir said, ‘that is what I follow’. Muhammad said, ‘you do not’. Abu ‘Amir said, ‘yes, I do’ and added that Muhammad had introduced in the Ḥanifiyya things which did not belong to it. Prophet Muhammad said, ‘I have not, I have brought it pure and white’.211 Exact nature of the differences between the two men is not known. Gil after thorough examination of wide range of resources concludes that Abu ‘Amar was a leader of a group of dissenters with ‘a kind of pacifistic orientation’ who were also opposed to ‘the new system of justice in Yathrib personified by Prophet Muhammad’.212

Above discussion on the Hanifs leads to the postulation that the Ḥanifs were monotheists, who claimed to follow ‘Dīn Ibrāhīm’, had reverence for the Ka’ba, and had close contacts with the Quraysh. Their break up with Prophet Muhammad appears to arise after hijra when he broke up with the Quraysh.213

Some Ḥanifs were pro-Muhammad as well and embraced Islam. Ibn Ishaq reports Poet Abu Qays Simra bin Abi Anas of Najjār clan from Medina who embraced Islam when Prophet Muhammad came to Medina, at an advanced age.214 Tha’labi in his commentary of the Qur’an mentions As’ad bin Zurara and Barra bin Ma’rur who were practicing shar’ia of the Ḥanifiyya and embraced Islam on the arrival of Prophet Muhammad.215

The most interesting personality among Ḥanifs is that of Zayd bin ‘Amr bin Nufayl. In his old age Zayd bin ‘Amr had a chance of having discussions with the Prophet Muhammad when the Prophet was still young.216 Ibn Ishaq reports that Zayd abandoned idolatry and did not embrace Judaism or Christianity. He rather insisted that he worshiped the Lord of Ibrahim. Ibn Ishaq attributes some verses to him in which he voices aversion to the worship of the daughters of Allah. In another verse, he professes his exclusive devotion to Allah.217 A purely monotheistic talabiya which he is said to have uttered during the hajj is also attributed to him.218 Ibn Ishaq reports that his paternal uncle Khaṭṭāb (father of caliph ‘Umar) forced him to leave Mecca. He had to live on Mount Ḥirāʾ, being able to enter Mecca only secretly. Khaṭṭab reportedly feared that other Meccans would follow Zayd in abandoning the old dīn of the Quraysh. 219 According to Ibn Ishaq Asma bint Abu Bakr reportedly said that she had seen Zayd leaning his back against the Ka’ba saying, ‘oh Quraysh, by Him in whose hand is the soul of Zayd, not one of you follows the religion of Ibrāhīm but I.220 Ibn Sa’d records that Zayd used to pray facing the Ka’ba, saying this is the qibla of Ibrahim and Isma’il. I do not worship stones and do not pray towards them and do not sacrifice to them and do not eat what was sacrificed to them and do not draw lots with arrows. I will not pray towards anything but this house till I die.221 Bayhaqi in Dala’il notes that Zayd used to say ‘I follow the religion of Ibrāhīm and I prostrate myself towards the Ka’ba which Ibrāhīm built’.222 Ibn Ishaq attributes this verse to Zayd which he used to utter when praying towards Ka’ba ‘I seek refuge in what Ibrāhīm sought refuge/when he was facing the qibla while standing (in prayer). 223 The Prophet Muhammad himself is reported to pray facing Ka’ba as qibla during the first years of his prophetic activity in Mecca.224

- Robert G. Hoyland. Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam (New York: Routledge, 2001), 139.

- John F. Healey, “The Nabataean tomb inscriptions of Mada’in Salih,” in Journal of Semitic Studies: suppliment (Oxford: Oxford University press,1993).

- Louis Jacobs. The book of Jewish Belief. Springfield: Behrman House, 1984.

- Philostorgius. Church History ed. and trans. Philip R. Amidon, (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2007), 41.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 123.

- Philippe Le Bas and William Henry Waddington. Inscriptions grecques et latines recueillies en Grece et en Asie Minneure (Paris: Firmin Didot Freres, 1870), vol. III, inscription 2558. The year given in the inscription is that of Seleucid era. Deir Ali is almost 30 km south of Damascus.

- John S. Trimingham, Christianity Among The Arabs in Pre-Islamic Times. London: Longman, 1978.

- Joseph Henninger, “Pre-Islamic Bedouin religion,” in Studies on Islam, ed. and trans. Meril Schwarz, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1981), 7.

- Geoffrey. R. D. King, “Some Christian wall Mosaics in pre-Islamic Arabia,” Proceedings of the seminar for Arabian Studies 10 (1980): 37 – 43.

- Wayne A. Grudem and Elliot Grudem. Christian Beliefs: Twenty Basics Every Christian Should Know. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2005.

- For contemporary Christian beliefs in the pre-Islamic period see Antiochus Stratego: F. Conybeare, “Antiochus Strategos’ Account of the Sack of Jerusalem (614),” English Historical Review 25 (1910), 502 – 517. Antiochus was a resident of Jerusalem in 615 CE during the last war of antiquity. He intersperses his Christian beliefs in his brief description of the events of the war. In between the narration of the war, he expresses his belief in Trinity, angels, the Bible, Heaven and Hell.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 121.

- Hasan b. Ahmad al Hamdani. Kitab sifat Jazirat al-‘Arab, ed. Ibrahim bin Ishaq al-Harbi, (Riyadh: Dar al-Yamama, 1974), 310.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 121.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 106.

- Mary Boyce. A History of Zoroastrianism. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1975. See also: Contractor, Dinshaw and Hutoxy, “Zoroastrianism: History, Beliefs and Practices,” Quest 91.1 (January – February 2003): 4 – 9.

- An inscription written on the ka’ba-ye Zartosht, near modern Shiraz, by a Zoroastrian high priest by the name of Kartir in the 3rd century CE reiterates contemporary Zoroastrian belief in Ahūra Mazda and Yazd as good god and Ahriman and devs as bad gods. It also talks about lighting sacred fires in many places. (Erich F. Schmidt Persepolis III, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970), 34 – 49). AND (W. B. Henning, The Inscription of Naqs-i-Rustam, (London: Lund Humphries, 1957), Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum series part III, vol. II, Portfolio II) AND Philip Huyse, Die dreisprachige Inschrift Sa.buhrs I. an der Ka’ba-i-Zardust (SKZ), (London, 1999) Corpus. Inscriptionum Iranicarum III Vol. I, Text I, p 6 – 7.

- Joseph Henninger, “Pre-Islamic Bedouin religion,” in Studies on Islam, ed. and trans. Meril Schwarz, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1981), 5.

- Joseph Henninger, “Pre-Islamic Bedouin religion,” in Studies on Islam, ed. and trans. Meril Schwarz, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1981), 8.

- Francis E. Peters. The Arabs and Arabia on the Eve of Islam: The Formation of the Classical Islamic World, (Surrey: Ashgate, 2010), XXIX.

- Maximus of Tyre. The Philosophical Orations, ed. and trans. M. B. Trapp, (Oxford: Clarendon press, 1997), 21-2. AND Clement of Alexandria. Clementis Alexandrini Protrepticus, ed. J C M Marcovich, (Leiden: E J. Brill, 1995), 71.

- Hisham Ibn al Kalbi. Kitab al Asnam, ed. and trans. Nabith Amin Faris. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952.

- Hisham Ibn al Kalbi. Kitab al Asnam, ed. and trans. Nabith Amin Faris, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952), 42.

- Joseph Henninger, “Pre-Islamic Bedouin religion,” in Studies on Islam, ed. and trans. Meril Schwarz, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1981), 11.

- Michael Lecker, “Idol Worship in Pre-Islamic Medina (Yathrib),” Le Museon 106 (1993): 331 – 46.

- Mircea Eliade. Patterns in comparative religion, trans. Rosemary Sheed, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996), 13.

- Michael Lecker, “Idol Worship in Pre-Islamic Medina (Yathrib),” Le Museon 106 (1993): 331 – 46.

- Michael Lecker, “Idol Worship in Pre-Islamic Medina (Yathrib),” Le Museon 106 (1993): 331 – 46.

- Hisham Ibn al Kalbi. Kitab al Asnam, ed. and trans. Nabith Amin Faris, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952), 40.

- Sayyid al-Murtadi al Zubaydi. Taj al-‘Urus (Kuwait; Matba’at al-Hukuma, 1965), vol. III p 517.

- Michael Lecker, “Idol Worship in Pre-Islamic Medina (Yathrib),” Le Museon 106 (1993): 331 – 46.

- Muhammad Ibn Ishaq. The Life of Muhammad, ed. and trans. Alfred Guillaume, (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2013), 35 -39.

- Hisham Ibn al Kalbi. Kitab al Asnam, ed. and trans. Nabith Amin Faris, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952), 24.

- Muhammad bin ‘Umar al-Wāqidī. The life of Muḥammad: kitāb al-Maghāzī, ed. Rizwi Faizer, trans. Rizwi Faizer, Amal Ismail and AbdulKader Tayob, (London: Routledge, 2011), 428.

- Hisham Ibn al Kalbi. Kitab al Asnam, ed. and trans. Nabith Amin Faris, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952), 18 -22.

- Muhammad Ibn Ishaq. The Life of Muhammad, ed. and trans. Alfred Guillaume, (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2013), 552.

- Hisham Ibn al Kalbi. Kitab al Asnam, ed. and trans. Nabith Amin Faris, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952), 16.

- Hisham Ibn al Kalbi. Kitab al Asnam, ed. and trans. Nabith Amin Faris, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952), 16.

- Hisham Ibn al Kalbi. Kitab al Asnam, ed. and trans. Nabith Amin Faris, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952), 16.

- Hisham Ibn al Kalbi. Kitab al Asnam, ed. and trans. Nabith Amin Faris, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952), 14.

- Hisham Ibn al Kalbi. Kitab al Asnam, ed. and trans. Nabith Amin Faris, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952), 22.

- Hisham Ibn al Kalbi. Kitab al Asnam, ed. and trans. Nabith Amin Faris, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952), 22.

- Qurʾan 71: 22-23.

- Hisham Ibn al Kalbi. Kitab al Asnam, ed. and trans. Nabith Amin Faris, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952), 24.

- Hisham Ibn al Kalbi. Kitab al Asnam, ed. and trans. Nabith Amin Faris, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952), 10.

- Hisham Ibn al Kalbi. Kitab al Asnam, ed. and trans. Nabith Amin Faris, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952), 22.

- Muhammad bin ‘Umar al-Wāqidī. The life of Muḥammad: kitāb al-Maghāzī, ed. Rizwi Faizer, trans. Rizwi Faizer, Amal Ismail and AbdulKader Tayob, (London: Routledge, 2011), 409.

- Muhammad Ibn Ishaq. The Life of Muhammad, ed. and trans. Alfred Guillaume, (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2013), 37.

- Muhammad bin ‘Umar al-Wāqidī. The life of Muḥammad: kitāb al-Maghāzī, ed. Rizwi Faizer, trans. Rizwi Faizer, Amal Ismail and AbdulKader Tayob, (London: Routledge, 2011), 409.

- Hisham Ibn al Kalbi. Kitab al Asnam, ed. and trans. Nabith Amin Faris, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952), 22.

- Muhammad Ibn Ishaq. The Life of Muhammad, ed. and trans. Alfred Guillaume. Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Uri Rubin, “Hanifiyya and Ka’ba: An Inquiry into the Arabian Pre-Islamic Background of Din Ibrahim,” Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 13 (1990): 104.

- Abu Muhammad b. Ahmad Ibn Qutayba. Kitab al-Sh’r wa-l-shu’ara, ed. M. J. De Goeje, (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1904), 110.

- Imru’ al Qays. Diwan. ed. Muhammad Abu al-Fadl Ibrahim, (Cairo: Dar al-Ma’arif, 1990), 101.

- Muhammad Ibn Ishaq. The Life of Muhammad, ed. and trans. Alfred Guillaume, (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2013), 172.

- Qur’an 29: 61-65.

- Muhammad Ibn Ishaq. The Life of Muhammad, ed. and trans. Alfred Guillaume, (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2013), 173.

- Muhammad bin ‘Umar al-Wāqidī. The life of Muḥammad: kitāb al-Maghāzī, ed. Rizwi Faizer, trans. Rizwi Faizer, Amal Ismail and AbdulKader Tayob, (London: Routledge, 2011), 300.

- Muhammad Ibn Ishaq. The Life of Muhammad, ed. and trans. Alfred Guillaume, (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2013), 62.

- Carl E. Sachau. Eine dreisprachige inschrift aus Zebed (Berlin: Monatsberichte der Koniglichen Preussische Akadamie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin, 1881), 169 -90.

- Laila Nehmé, “New Dated Inscriptions (Nabataean and Pre-Islamic Arabic) from a Site Near Al-Jawf, Ancient Dūmah, Saudi Arabia,” Arabian Epigraphic Notes 3(2017): 124 -129. (DaJ14Par1) photo on page 126. 121 – 164.

- Jozef Takeusz Milik, “Inscriptions grecques et Nabateenes de Rawwafah,” in Preliminary Survey in N. W. Arabia 1968, Peter J. Parr, Gerald L. Harding and John E. Dayton, bulletin of the Institute of Archaeology 10 (1971): 54 – 58. (CIS ii no. 3642a).

- Muhammad Ibn Ishaq. The Life of Muhammad, ed. and trans. Alfred Guillaume, (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2013), 37.

- Muhammad Ibn Ishaq. The Life of Muhammad, ed. and trans. Alfred Guillaume, (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2013), 239.

- Muhammad Ibn Ishaq. The Life of Muhammad, ed. and trans. Alfred Guillaume, (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2013), 271.

- Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani. Al- Isaba fi tamyiz al-Sahaba (Calcutta: Bibliotheca Indica, 1853 – 94), vol. I P 692.

- Ibn Hajar, al-Asqalani. Al- Isaba fi tamyiz al-Sahaba (Calcutta: Bibliotheca Indica, 1853 – 94) vol. I P 874.

- Ahmad Ibn Hanbal. Musnad (Cairo: 1895. Reprinted Beirut: al-Maktab al-Islami Li’l- Tiba’a wa’l-Nashr, 1969) Vol. III P 419.

- Julius Wellhausen. Reste Arabischen Heidentums. Berlin – Leipzig: W. De Gruyter & Co. 1887, reprinted 1927.

- 66. Qur’an 40:12.

- Qur’an 39:3.

- Qur’an 10: 18.

- Quran 30:12,13.

- Muhammad Ibn Ishaq. The Life of Muhammad, ed. and trans. Alfred Guillaume, (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2013), 635.

- 71. Hisham Ibn al Kalbi. Kitab al Asnam, ed. and trans. Nabith Amin Faris, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952), 7.

- Meir J. Kister, “labbayka, allahumma labbayka……on a monotheist aspect of a jahiliyya practice,” Jerusalem studies in Arabic and Islam 2 (1980): 47 – 49.

- Muhammad Ibn Ishaq. The Life of Muhammad, ed. and trans. Alfred Guillaume, (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2013), 50.

- Ma‘mar ibn Rāshid. The Expeditions, ed. Joseph E. Lowry, trans. Sean W. Anthony. (New York: New York University Press, 2015), 4.

- Muhammad Moinuddin Ahmad. Masai’l-o-Ma’lumat-e-Hajj-o-Umrah (Karachi: Al Muin Trust, 1984), 1 – 89.

- Hisham Ibn al Kalbi. Kitab al Asnam, ed. and trans. Nabith Amin Faris, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952), 7.

- Fabietti Ugo, “The Role Played by the Organization of the ‘Hums’ in the Evolution of Political Ideas in Pre-Islamic Mecca,” Proceedings of the seminar for Arabian Studies 18 (London; 1988): 25 – 33.

- Meir J. Kister, “Mecca and Tamim,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 8 (1965): 113 – 163.

- Walter Dostal, “Mecca before the Time of the Prophet – Attempt of an Anthropological interpretation,” Der Islam 68, no. 2 (1991): 214.

- Tirmidhi. Kitab al Sahih (Cairo: Babi, 1292/1875) vol. I P 167.

- Walter Dostal, “Mecca before the Time of the Prophet – Attempt of an Anthropological interpretation,” Der Islam 68, no. 2 (1991): 193 -231.

- Richard F. Burton. Personal Narrative of a Pilgrimage to Al-Madinah & Meccah. London Tylston And Edwards, 1893.

- Muhammad Ibn Ishaq. The Life of Muhammad, ed. and trans. Alfred Guillaume. Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Al Fakihi. Tarikh Makka. MS Leiden Or. 463 fol. 380 (a).

- Muhammad bin ‘Abdullah Al-Azraqi, “Kitab Akhbar Makka wa ma ja’a fiha min al-athar” in Die Chroniken der stadt Mekka, Vol I. ed. Ferdinend Wustenfeld. (Leipzig: F. A. Grockhaus, 1858; reprint Beirut: n. d.): 74 – 75; 49 – 50.

- Al-‘Asqalani. Fath al-Bari sharh sahih al-Bukhari. Vol. III P 400.

- Al Fakihi. Tarikh Makka. MS Leiden Or. 463 fol. 380 (a).

- Uri Rubin, “The Ka’ba: aspects of its Ritual Functions and Position in Pre-Islamic and Early Islamic Times,” Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 13 (1986): 99 – 131.

- Muqatil b. Sulayman. Kitab Tafsir al-Khams Mi’ah aya min al-Quran, ed. I Goldfield, (Syfaram: Al-Masyriq press, 1980): Vol. I P 25.

- Muhammad bin ‘Abdullah Al-Azraqi, “Kitab Akhbar Makka wa ma ja’a fiha min al-athar” in Die Chroniken der stadt Mekka, Vol I. ed. Ferdinend Wustenfeld. (Leipzig: F. A. Grockhaus, 1858; reprint Beirut: n. d.): 75, 121.

- Uri Rubin, “The Ka’ba: aspects of its Ritual Functions and Position in Pre-Islamic and Early Islamic Times,” Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 13 (1986): 99 – 131.

- Muhammad bin ‘Umar al-Wāqidī. The life of Muḥammad: kitāb al-Maghāzī, ed. Rizwi Faizer, trans. Rizwi Faizer, Amal Ismail and AbdulKader Tayob. London: Routledge, 2011.

- Uri Rubin, “The Ka’ba: aspects of its Ritual Functions and Position in Pre-Islamic and Early Islamic Times,” Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 13 (1986): 99 – 131.

- Muhammad bin ‘Umar al-Wāqidī. The life of Muḥammad: kitāb al-Maghāzī, ed. Rizwi Faizer, trans. Rizwi Faizer, Amal Ismail and AbdulKader Tayob. London: Routledge, 2011.

- Al Fakihi. Tarikh Makka. MS Leiden Or. 463 fol. 277 (a)

- Al Fakihi. Tarikh Makka. MS Leiden Or. 463 fol. 276 (a)

- Muhammad Ibn Ishaq. The Life of Muhammad, ed. and trans. Alfred Guillaume. Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- al-Baladhuri. Ansab al ashraf. Ed. M. Hamidullah. (Cairo: Dar al-Ma’arif, 1959) Vol. P I 81-83.

- Muhammad bin ‘Abdullah Al-Azraqi, “Kitab Akhbar Makka wa ma ja’a fiha min al-athar” in Die Chroniken der stadt Mekka, Vol I. ed. Ferdinend Wustenfeld. (Leipzig: F. A. Grockhaus, 1858; reprint Beirut: n. d.): 154-155.

- Uri Rubin, “The Ka’ba: aspects of its Ritual Functions and Position in Pre-Islamic and Early Islamic Times,” Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 13 (1986): 99 – 131.

- Muhammad bin ‘Abdullah Al-Azraqi, “Kitab Akhbar Makka wa ma ja’a fiha min al-athar” in Die Chroniken der stadt Mekka, Vol I. ed. Ferdinend Wustenfeld. (Leipzig: F. A. Grockhaus, 1858; reprint Beirut: n. d.): 121.

- Muhammad Ibn Ishaq. The Life of Muhammad, ed. and trans. Alfred Guillaume. Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Muhammad bin ‘Abdullah Al-Azraqi, “Kitab Akhbar Makka wa ma ja’a fiha min al-athar” in Die Chroniken der stadt Mekka, Vol I. ed. Ferdinend Wustenfeld. (Leipzig: F. A. Grockhaus, 1858; reprint Beirut: n. d.): 75.

- Ma‘mar ibn Rāshid. The Expeditions. Ed. Joseph E. Lowry, Trans. Sean W. Anthony. (New York: New York University Press, 2015) 4.

- Al Fakihi. Tarikh Makka. MS Leiden Or. 463 fol. 338 (A), 338 (B).

- Uri Rubin, “The Ka’ba: aspects of its Ritual Functions and Position in Pre-Islamic and Early Islamic Times,” Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 13 (1986): 117.

- Muhammad bin ‘Abdullah Al-Azraqi, “Kitab Akhbar Makka wa ma ja’a fiha min al-athar” in Die Chroniken der stadt Mekka, Vol I. ed. Ferdinend Wustenfeld. (Leipzig: F. A. Grockhaus, 1858; reprint Beirut: n. d.): 73, 169-170. The treasure was still there in Ka’ba during ‘Umar bin Khattab’s tenure. He wished to seize it and use in the cause of Allah (state). Ubai bin Kalb of Anṣar resisted him on the grounds that Prophet Muhammad and Abu Bakr had not done it. (Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 69.

- Joseph Chelhod, “Le Sacrifice chez les Arabes. Recherches sur l’èvolution, la nature et al function des rites sacrificiels en Arabie occidentale,” Revue de l’histoire des religions 150, no. 2 (1956): 232 – 241.

- Joseph Chelhod, “Le Sacrifice chez les Arabes. Recherches sur l’èvolution, la nature et al function des rites sacrificiels en Arabie occidentale,” Revue de l’histoire des religions 150, no. 2 (1956): 232 – 241.

- Abu Hayyan al-Tawhidi. Kitab al imta’ wa-l-mu’anasa, ed. A. Amin and A. al-Zayn, (Cairo: 1939 – 1953): Vol. I P 85.

- Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti. Al-durr al-manthur (Cairo 1896. Repr. Beirut n.d.), Vol. IV P 410.

- Muhammad bin ‘Umar al-Wāqidī. The life of Muḥammad: kitāb al-Maghāzī, ed. Rizwi Faizer, trans. Rizwi Faizer, Amal Ismail and AbdulKader Tayob, (London: Routledge, 2011), 216.

- Muhammad Ibn Ishaq. The Life of Muhammad, ed. and trans. Alfred Guillaume. Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti. Al-durr al-manthur (Cairo 1896. Repr. Beirut n.d.), Vol. I P 143.

- Muhammad Baha’ al-Din abu-l-Baq’ al-‘Adawi. Ahwal Makka wa-l-Madina. Ms. Br. Library, OR. 11865 P 122 (B), 123 (A).

- Muhammad bin ‘Abdullah Al-Azraqi, “Kitab Akhbar Makka wa ma ja’a fiha min al-athar” in Die Chroniken der stadt Mekka, Vol I. ed. Ferdinend Wustenfeld. (Leipzig: F. A. Grockhaus, 1858; reprint Beirut: n. d.): 267.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVI, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 222. AND 116. Muhammad bin ‘Umar al-Wāqidī. The life of Muḥammad: kitāb al-Maghāzī, ed. Rizwi Faizer, trans. Rizwi Faizer, Amal Ismail and AbdulKader Tayob, (London: Routledge, 2011), 411.

- Muhammad Ibn Ishaq. The Life of Muhammad, ed. and trans. Alfred Guillaume, (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2013), 552.

- J. Wellhausen. Reste arabischen Heidentums 3rd ed (Beriln: 1961), 74.

- Josephus Flavius. Antiquitates Judaicae, trans. William Whiston, (New York: David Huntington, 1815): book I chap xii paragraph 2.