The politics of the Middle East during the 5th and 6th centuries CE were complex. Arabia was surrounded by regions that had organized themselves into states thousands of years ago and were governed by absolute monarchs. Arabian Peninsula itself had two political zones. The zone of state power, consisting of states or state-like structures and a zone of nomadic power, is inhabited and governed by constantly feuding tribes. Interaction between states surrounding Arabian Peninsula, state or state-like structures within Arabian Peninsula and the tribal zone of Arabian Peninsula created a constantly changing political scenario. We shall survey different regions one by one to see the political snapshot of each region. Then, by combining all snapshots with the power of imagination, the reader can visualize the bigger picture.

State vs. non-state

Fertile Crescent (Syria and Iraq) and South Arabia (Yemen), due to their ecological conditions, had historically permitted the rise of highly centralized, hierarchical and bureaucratized political structures (‘state’) built on an agricultural tax base. Northern and Central Arabia, because of their vast extent, difficulty of access, and meagre resources, had generally laid outside state control, and in the successive confederations of pastoral nomads were, from about the third century BCE onward, able to establish their control over local settlements. These confederations were not true states. They were instead state-like organizations governed by tribal traditions. Within the zone of nomadic power, the political life of sedentary people of towns and villages was shaped by power struggles among nomad population. In some cases, towns or villages were simply subjugated by nomads and were forced to pay taxes. In others, a town was ruled by a leading family that kept its position by maintaining a network of alliances with nomadic groups. Nomads in these alliances enhanced the ruling family’s influence in exchange for economic or other benefits. In some cases, a nomadic group might ‘capture’ a town and establish its own leaders as the town’s ruling family—a family that ruled partly by utilizing its close ties to its nomadic followers. Examples of this process abound from late antiquity (Palmyra, Hatra, Edessa) right up to modern times. In zone of state power, for example in Syria, Iraq or Yemen, relationships between nomadic groups and local power structures were somewhat different. Nomads living in the state zone were not autonomous foci of power. They fell under the surveillance and the taxing power of the state. State prevented nomads from controlling settled communities directly, or at least seriously limited such control. However, states often allowed nomads to work out mutual power relationships with other nomadic groups by themselves. The states of the regions under consideration had generally given high priority to preventing nomads from raiding, ‘capturing’ or taxing towns within their territory.1

Early Islamic historians have coined the term Jahiliyyah (Jāhiliyyah جاهِليه) to describe the chaos that prevailed in the zone of nomadic power during 5th and 6th centuries, before the advent of Islam.2 The term Jahiliyyah might be pointing to the spiritual ignorance of that era but it also definitely pinpoints the political and social chaos that existed. There is a unanimous agreement among historians that during the fifty years or so before the advent of Islam nomadic zone of Arabia was a devastated and ruined land, but this unanimity tends to disintegrate when discussion about the origins of the disaster starts. Do the roots of the crisis extend back several centuries, or was it caused by a sudden collapse following wars, massacres and epidemics (like the famous ‘plague of Justinian’) a few decades ago is still a paradox.3, 4. Some historians have suggested environmental changes behind the economic crisis.5

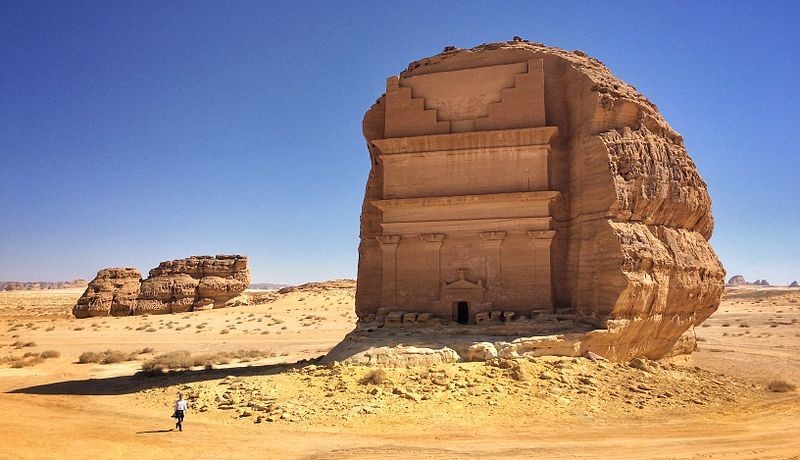

We know that Central and Northern Arabia had organized states and state-like strong structures at one point in its history before Islam, which later deteriorated gradually. If we go back as far as 100 CE we find strong states scattered all over Arabia. In the northwest, the kingdom of the Nabataeans stretched as far as some kilometres south of Hegra/Egra/al-Ḥijr (Present day Madain Saleh), including Tayma in the east.6 Then there was the kingdom of Lihyan, at that time only a city-state restricted to Dedan (present-day al Ula) and its surroundings. A number of similar structures extended up to the frontiers of the South Arabian Kingdoms of Saba’ and Du Raidan (of the Sabaeans and Ḥimyarites respectively). Finally, the kingdom of Hadarmaut (Ḥaḍarmaut حَضَرمَوت) existed in the very south. In the east were the two city-states of Gerrha, (present-day Hufuf), and Hatt/Qatif. In the district of the northern frontier, Palmyra (Tadmor تدمر), and in the northeast the petty principalities of the league of the Arsacides dynasty of Parthians extended to Characene. (a vessel state of Arsacides located at present-day Kuwait).

Qasr al Farid: biggest tomb in archaeological site of Mada’in Saleh. 7

Usually mentioned along with Thamud is another tribe by name of ‘Ād ((عاد. Historically, Ad was a tribe on the borders of Madain and southern Transjordan, where the ruins of the temple, Iram, with which its name was associated, still exists. (modern remains in the village of Shisr in the Dhofar region of Oman. 9 Though occasionally booty is mentioned, on the whole, the milieu seems to have been much more peaceful than in later times. In 106 CE the northern part of the Nabataean kingdom was incorporated into the Roman Empire. A temple, the columns of which are still standing, was erected between the end of 166 CE and the beginning of 169 CE in honour of the Emperors Marcus Aurelius Antoninus and Lucius Aurelius Verus at Rawwafa about 115 Km southwest of present-day Tabuk (Tabūk تَبوُك), confirming state influence in the region.10 Greek inscriptions by soldiers on the road about 10 km from al-Ula (Dedan) are another proof that state influence was present by that time.11 The last Lihyanic inscription dates from the time immediately after that. It reads “ ‘Anaza bin Aus bin Tunil bin ‘Abd, Du Al [Clan name] Hani’-Hunkat took Nauf ha-Ulur prisoner in al-Ḥijr in …. the year when the evildoers were caught. Therefore, the assembly of the people has instructed me for three years with the protection of the road.”12 One can notice the decline. There is no longer state influence as indicated by the fact that the era of Bosra, formerly used in Dedan, is no longer in use. The date is given in Bedouin manner instead. The protector of the road is instructed to do so by the assembly of people instead of a state. The long genealogy is also somewhat Bedouin in character. Such evidence brings to light the historical fact that the state influence gradually shrank in Arabian Peninsula and gave way to a nomadic zone by the 3rd century CE.13 It is plausible that the state influence gradually gave way to state-like tribal entities, and tribal confederations, which ultimately vanished by the middle of the 6th century CE after the death of Abraha, the Yemeni king.

Incense trade, which was the lifeline of state influence in Arabia, ceased exactly after 25 BCE when a Roman army attacked Arabia and reached Yemen. Once they discovered the caravan route and the land of incense, they turned the trade to the sea.14 Decline in state influence in northern and central parts of Arabia coincides with a decline in incense trade. As trade contracted, the economy collapsed. The population that depended on trade took to nomadic life. Because of constant insecurity in the Syrian Desert, caused by the periodic immigration from the south, Bedouin life developed earlier in northern Arabia than in central Arabia where circumstances necessitated it only later.15

The Nomadic Zone

During the centuries immediately prior to the advent of Islam a number of tribes inhabited the regions we call ‘zone of nomadic power’ in central and northern Arabia. They ran their affairs in light of tribal traditions. They were constantly in strife with each other, changing their allegiances and enmity in this process frequently. Allegiances and enmities changed so rapidly, evident from an example of the relationship between Tai (Ṭāʾī طاءِى), Ghatafan (Ghaṭafān غَطَفان) and Asad tribes. They used to be in alliance with each other. A few years later, sometimes just before the advent of Islam, the relationship changed. Ghatafan and Asad joined hands to chase the Tai away from their lands in Jadilah and Ghawth. Later on, during Ridda Wars, the relationship changed again. Many Tai clans sided with Ghatafan and Asad against the forces of the Medinan Caliphate.16 Constant fighting among Arabs kept the population sufficiently small for the meagre resources of the desert to support.17 As tribes were always dagger drawn at each other, they had to involve surrounding states to strengthen their respective position as compared to their opponents. Despite having auxiliary relations with foreign states, the nomadic zone never organized itself in a true state. Bedouins hated being subject of a state. “The Himasi does not defend his honour, but is like the Mesopotamian peasant who patiently endures when one enslaves him,” says Hassan bin Thabit (Ḥassān bin Thābit حَسّان بِن ثابِت) taunting tax paying tribesman.18 By the time of the dawn of Islam very few tribes were left without any kind of affiliation with a foreign power, anyhow. Like their own internal politics of frequently changing allegiance and enmity, they used to switch their allegiance to foreign powers at their convenience. The extent of influence of surrounding states over the nomadic zone during pre-Islamic centuries and changes in it will be discussed later along with a description of respective states who influenced it.

The tribes sometimes organized themselves into confederations of tribes by joining hands as confederates (حليف, ḥalīf). Such tribal confederations had played a significant political role in the nomadic zone after declining in state influence. However, it appears that a few decades before the advent of Islam, they were not that influential. There were few such organizations at that time. One of them, that dominated Central Arabia, and was comparatively large was called Bakr bin Waʾil (Bakr bin Wā’il بَكر بِن واءِل). This grouping included Banu Shayban, Banu ‘Ijl, Banu Qays, Banu Tha’labah (ثَعلَبَه), Banu Dhuhl (زُهٌل), Banu Taymallat (Taym Allāt تَيم الّاة), Banu Yashkur (يَشكَر) and Banu Hanifa (Ḥanīfāh حَنِيفَه).19 Al-Lahazim was another confederation headed by Bujayr bin Bujayr al-‘Ajali.20 Banu Tamim (Tamīm تَمِيم) deserves special mention here as they were the largest tribe of Central Arabia scattered throughout Nejd, Yamama and Bahrain.21 Banu Ghatafan were another big tribe. Actually, some historians believe that Ghatafan and Tamim had grown so big by absorbing weaker tribes that they could be considered geographical entities.22 It is worth noting that the tribe was too big to accommodate the political aspirations of all consisting clans. Resultantly, these were mainly clans that were acting as sovereign political units.23

Almost all Arab tribes in pre-Islamic Arabia had both sedentary and nomadic clans. Though each of them was predominantly settled or roamed in one specific area, small clans of a tribe might have scattered all over Arabia. Hence precise mapping of areas dwelt by each tribe is impossible. The situation becomes more bewildering when we find that the early Islamic sources call each group irrespective of size ‘banu so and so’ mingling clans with tribes. The situation becomes more bewildering when we find clans of the same name but from different tribes and the names of tribes are written similarly to the name of a person like ‘so bin so’ and the source assumes that the reader knows it.24 The map above gives a rough guide to the geographical distribution of prominent tribes of that time. 26 Tabari mentions two Azds in an odd, Azd Shanūah and Azd ‘Umān. They participated in the tribal warfare in Basrah during the Umayyad period under a single leader by name of Abdur Rahman bin Mikhnaf. 27

Clues exist that despite anarchy in the nomadic zone, there were lone voices favouring nation formation.28 In an interesting pre-Islamic inscription ‘the community of ‘Athtar’ is mentioned. It is very near to Prophet Muhammad’s concept of ummah floated later.29 These kinds of clues have led some historians to believe that Arab tribes were already en route to state formation on the eve of Islam.30

Byzantine Rome

In the northwest of the Arabian Peninsula, there was a powerful state that is called Byzantine Empire by modern historians. It was a superpower of the time and used to influence political events taking place in Arabian Peninsula. Byzantine Empire is named after its capital city Byzantium, whose name was later changed to Constantinople (قسطنطنيه, Qustuntunia of early Arabic sources, present-day Istanbul) by Emperor Constantine in 330 CE. Its citizens used to call their country Roman Empire (or simply Romania) because it emerged from the ruins of the Roman Empire in the 5th century CE.31 This predominantly Greek-speaking country was officially Christian. The population of this big country is estimated to be twenty to twenty-five million subjects at one stage.32

Its ruler, an absolute monarch, was called Basileus. Basileus is referred to as Qaiser (قيصر) by Arabic sources, a word derived from Caesar. After its inception, the Byzantine Empire progressively expanded reaching its largest size in 555 CE during the reign of Justinian I. At that time, it governed vast stretches of land surrounding the Mediterranean Sea. Its sovereignty extended from Rome (Italian peninsula) over to the Balkans in Europe, from Anatolia in Asia to Phoenicia (Lebanon), Levant and Palestine in the Middle East, from Egypt (Miṣr مصر), Libya and Carthage (Tunisia) to the whole coast of north Africa, and lastly across Gibraltar to southern parts of Iberian peninsula in Europe.33, 34 At that time area controlled by Byzantine Rome is calculated to be 3.4 million square kilometres and its population to be 19 million.35 This powerful state had a fully developed justice system of courts, bureaucracy and a standing army. The government was divided into specialized departments like those responsible for policing or construction and maintenance of roads etc. Byzantine possessed enough means to muddle with affairs of Arabia. The economic strength of the Byzantine Empire can be guesstimated from the fact that their golden coins, officially named Solidus and unofficially nicknamed Dinar (Dinār دينار), were accepted all over, including Arabian Peninsula.36, 37

Hagia Sophia: Church of Constantinople built by Byzantine. 38

His successor Justin II, who ruled from 565 to 578 CE, stubbornly refused to pay annual tributes to the Sasanians. Consequently, the empire lost its greater portion during his reign. Tiberius II ruled Byzantine Rome for a short period of four years after Justin II. Then came almost two decades of Maurice from 582 to 602 AD. Maurice considered Rome strong and secure. When civil war erupted in neighbouring Iran, Maurice quickly intervened by placing the legitimate candidate Khosrau II Parvez on the throne and giving his daughter to Khosrau II Parvez in marriage. Maurice’s rule ended abruptly when his general Phoscas usurped power and murdered Maurice.39 Phoscas could not hold power for a long time and Heraclius (harcūlīs هرقل) deposed him in 610 CE. Heraclius ruled Byzantine Rome from 610 to 641 CE and it was he who faced the first attacks of Arab armies under the banner of Islam. Events that took place inside Byzantine on eve of Islam will be discussed later.

Sasanian Iran

In the northeast of the Arabian Peninsula, there was another state. It was as powerful as Byzantine Rome itself and was rival to it. It is called Sasanid Empire (Sāsān سا سا ن) by modern historians after the name of its ruling dynasty. Its citizens, anyhow, used to call it Eranshahr or simply Eran.40 Sasanid Empire rose in 224 CE with its capital at Tysfwn.41 Sasanian ruler, another absolute monarch, called himself Shahanshah. Arabs named the Shahanshah as Kisra کسرݵ)), a word derived from Khosrau. The Sasanian territory was not only comprised of mainland Persia but also Mesopotamia (Jazīrah). In Asia, it stretched almost to Central Asia and to the River Indus in India. In Europe, it protruded up to Caucasia.42

Taq Kasra; ruined palace of Sassanids at Ctesiphon. 43

Though the official religion of the Sasanid state was Zoroastrianism, it exhibited extreme religious tolerance. Like Byzantine Rome, the Sasanians had the power and resources to shape political events occurring in Arabia and were participating in such events actively. Being an economic contender to Byzantine Rome, their silver Dirham was also accepted all over including Arabian Peninsula.45

By the turn of the 6th century CE, the Sasanian ruler was Qubad (Kavadh I, Qubād, قباد). His son Khosrau I, also called Nawshirvan (خُسرَو نَوشِيروان), succeeded him in 531 CE. Greek sources name him Chosroes. Khosrau’s rule continued up to 579 CE. Hormizd IV took the throne after Khosrau and ruled the country up to 591 CE. Hormizd was succeeded by his son Khosrau II, also called Khosrau Parvez (خُسرَو بَروِيز), who governed the empire from 591 to 628 CE. Khosrau II was the last effective ruler of the Sasanid Empire. The political stability of the country dwindled fast after his murder.46 We shall discuss it later.

Ethiopia

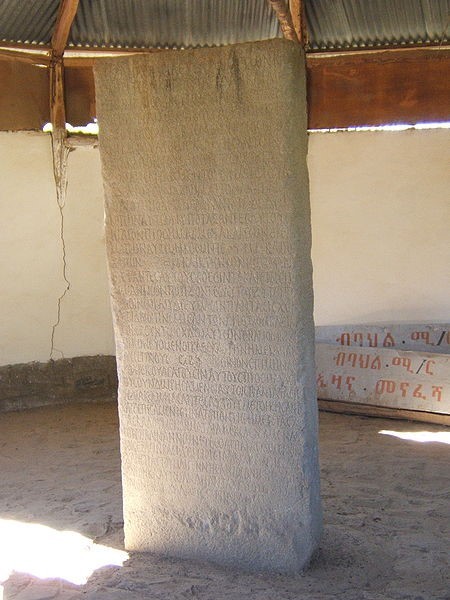

The third strong role player in the region was a kingdom located at the horn of Africa. Named the kingdom of Axum (Aksum) by modern historians after its capital city, the kingdom itself was called Ethiopia (Ḥabshah حبشه in early Islamic sources) by its inhabitants.47 Title of its king was ngš ngšt. ngš ngšt is referred to as Najāshī (نجاشى) in early Arabic sources.48 (Negus in English). This trading nation rose to prominence around 100 CE and survived up to 940 CE. It was one of the earliest nations to adopt Christianity.49 Mani, a 3rd century CE Iranian scholar, considers it one of four great powers of the word, others being Rome, Persia and Sileos (China).50

King Ezana’s Stela: an Axumite architecture.51

Arab power of Lakhmids

After a brief introduction to the world powers surrounding Arabia, let’s look at the small powers that existed inside Arabia.

In the northeastern corner of the Arabian Peninsula was the land of Iraq (Al-‘Irāq العراق). Sandwiched between Sasanian Iran and Arabia proper, it was inhabited by Arab tribes both nomads and sedentary. They were allied to the Sasanians. Sasanians did not annex Iraq to their empire. Rather they kept it as a buffer zone between themselves and Byzantine Rome on the one hand and between themselves and the nomadic zone of northern and central Arabia on the other hand. Sasanians used to appoint somebody from the tribe of Lakhm as king of Iraq. This king was not a governor. Neither was he a fully-fledged sovereign. He did not pay any tributes to the Sasanians but was always appointed by them. He used to act as a semi-independent ruler. As Tabari puts it ‘They (the clan of Nasr bin Rabi’a of the tribe of Lakhm) became rulers because the Sasanian kings employed them for this purpose, relying on them to keep the adjacent Arabs under control.’53 Capital of the Lakhmids (al-Lakhmiyyūn اللخميون) was Hirah (Hīraḥ هيرح).54

A victory inscription of the Shahanshah Narseh (293 – 302 CE) located in Iraqi Kurdistan and known as Paikuli inscription enumerates the kings who recognized Narseh as king of kings, Shahanshah. One of those kings is ‘Amru, king of the Lakhmids.’55 This is the earliest extant mention of lakhmids. In 5th and 6th centuries CE lakhmids were well established. During these two centuries, they not only took part in Iran-Rome wars from Sasanian side but also exerted influence in Hejaz, Yamama and Bahrain on behalf of the Sasanians.56

Ruins of al Ḥīraḥ.57

According to Abu l-Baqa lakhmids had income for fiefs in Iraq but the bulk of their revenues came from the profits gained from trade, from the booty of their raids against Bedouins, against the borderlands of Syria and against every territory they could raid and from the collection of taxes from the obedient tribes; they collected in this way great quantities of cattle.59

One job of the Lakhmids was to secure influence among tribes of Arabia either for themselves directly or through themselves for the Sasanians. In order to secure the loyalty and cooperation of the chief of a tribe, some prerogatives of the ruler were ceded to him. To meet this end, they created an institution of ‘ridafa’. The ‘ridf’ sat in the court of the Lakhmid king on his right hand, rode with the king, got a fourth of the spoils and booty of the raids gained by the king and received some payment from the king’s subjects.60 Yarbu, a clan of Tamim and Sadus (of Sayban), a clan of Taghlib (تَغلِب) are mentioned in sources as being ridf.61

Another institution of the Lakhmids during the second part of the sixth century CE, and established on a similar principle as that of ridafa, was ‘Dawu l-akal’. They were the chiefs of tribes who were awarded fiefs. This institution is mentioned by Ibn Habīb (d. c. 859 CE) as well as by pre-Islamic poet al-A’sha. Some clans of Tamim, who were residents of Yamama and adjacent regions, were given fiefs by the Lakhmids.62 Qays bin Mas’ud of the Shayban tribe was granted lands of Taff Ubulla by Khosrau II Perwez (after the death of Nu’mān III, the Lakhmid king) against a guarantee that Bakr bin Waʾil would refrain from raiding the territory of the Sawad.63 Abu l-Baqa records that some of the fief given to Nu’man (Nu’mān III, نُعمان) by the Shahanshah was located in Hejaz. An annual tax collected from them was a hundred thousand Dirhams and the yield was thirty thousand karr in addition to fruits and other produce. Nu’man, in turn, had granted some of them to Sawad bin ‘Adiyy from Tamim.64 In addition to the above-mentioned ways, the lakhmids had many other methods to favour chiefs of friendly tribes. They appointed leaders of friendly tribes as collectors of taxes, as commanders of divisions of their forces and as officials in territories in which they exercised some control. ‘Amr bin Sarik was in charge of Lakhmid Kings Mundhir’s (مَنذِر) and Nu’man’s police. Sinan bin Malik of Aws manat (Aws Manāt اَوس مَنات, a clan of Amir bin Qasit tribe) was governor of Ubulla for Nu’man.65

Despite Sasanian backing, Lakhmids could not subjugate all Arab tribes of central and northern Arabia. According to Abu l-Baqa there were three types of Bedouin tribes: Laqah, the independent tribes who raided territories of the Lakhmids and were raided by them. The tribes had pacts with the lakhmids on certain terms. And the tribes who were obedient to lakhmids when they were pasturing in their territories but did not obey them when away from their territories. The nearest neighbours of the lakhmids were Banu Rabi’a and Tamim. Banu Asad bin Khuzaymah and Ghatafan were laqah. Banu Sulaym (سليَم) and Banu Hawazin (Hawāzin هوازِن) had pacts with the Lakhmids. They were not submissive to lakhmid but escorted the king’s caravans to Nejd. Sometimes they took part in raids along with the king.66 Banu Mudar, who was part of the confederation of tribes with Tamim, were independent of Lakhmids.67, 68 Ibn Habib reports that Asad and Ghatafan were allies, not submitting to obedience to the Lakhhmids. ‘Amr bin Masud and Khalid bin Nandla of Asad used to visit Nu’man every year, stay with him and drink with him. Nu’man asked them to come to his obedience like Tamim or Rabi’a so he could defend them. They politely refused, saying his lands were not suitable for their herds. Nu’man ordered to poison them.69 Each tribe’s relations with the lakhmids kept on changing over time.70

Refusal to pay taxes could be a reason for Lakhmid’s raid on friendly tribes. One such raid took place on Tamim. Brother of Nu’man, Rayyan bin Mundhir, carried it out with the help of troops recruited from Bakr bin Waʾil.71 Another reason for Lakhmid’s raid could be an attack on their trade caravan. For example, according to Baladhuri, a 9th-century Islamic source, Nu’man equipped his brother Wabara bin Runamis with the strong force of Ma‘add (مَعَد) and others to fight against Zirar bin ‘Amr of Dabba clan of Amir bin Sasa’ah (‘Āmir bin Ṣa’ṣa’ah عامِر بِن صعصعه). Ibn al-Athīr, a 13th-century Kurd scholar writing in Arabic, gives the reason for this attack was in retaliation to an attack by Amir bin Sasa’ah on a caravan of Nu’man and his allies that was sent to ‘Ukaz. When Quraysh returned from ‘Ukaz to Mecca, Wabara attacked Banu ‘Amir. Waraba was defeated and captured by a warrior and poet Yazid bin Sa’iq. He returned Waraba to Nu’man after getting a ransom of one thousand camels, two singing girls and an allotment of possessions. This event is called the raid of al-Qurnatayn. Ibn al-Athir stresses that Amir bin Sasa’ah were Laqah and were ‘Hums’ confederating with Quraysh. That is the reason ‘Abd Allah bin Gud’an of Quraysh had warned Banu Amir of this attack in advance and they could prepare themselves for the fight.72

The Lakhmids reached the zenith of their power in the first half of the 6th century after defeating Kindah (كِنده) king Harith bin Amr (Ḥārith bin ‘Amr حارِث بِن عمرو) in 529 CE. According to Tabari Khosrau I Nawshirwan made Mundhir (called Alamoundaras by Procopius), the Shaykh of the Lakhmids, king over Oman, Bahrain, Yamama and the neighbouring parts of Arabia as far as the town of Taif (Ṭāʾif طاءِف) in the Hejaz.73 This event might have taken place shortly after 531 CE because that is the year when Khosrau I Nawshirwan came to power. Whatever the truth of this assertion, Mundhir was certainly exercising sovereignty over the confederation of the Ma‘add in Central Arabia towards the middle of the sixth century and it was he against whom Abraha sent an expedition from Yemen.74 Actually, all events of interaction between Lakhmid and the nomadic zone of central and northern Arabia mentioned above would have taken place between the defeat of Harith bin ‘Amr in 529 CE and Lakhmid’s fall from power by 602 CE (see below). There could be a transient decrease in Lakhmid influence in Arabia when Abraha rose to dominance in 553 CE and remained so until his death.

The second most important job of Lakhmids was to fight along with Sasanians against Byzantine and their Ghassan (Ghassān غَسّان) Arab allies. Some of them were full-scale wars taking great tolls on both sides. Mundhir was killed in 554 CE in a battle with Harith bin Jabalah (Ḥārith bin Jabalah حارِث بِن جَبَلَه, called Arethas by Procopius) of Ghassans. The day he was killed is called Yawm Halima.75

Despite their interdependence, the atmosphere of mistrust between the Lakhmids and the Sasanians can be traced throughout their relationships. Mistrust was not only a sign of friction between two political entities but also between two cultures, Arab and Ajam (عجم). (Arabs used to call Iranians Ajami). Hatred for each other is illustrated from the opinions the two camps have expressed about each other and are usually put together in a dialogue form that has attained legendary fame. Khosrau I Nawshirvan is said to have stated, “I see no good in the Arabs – materially and spiritually – they have no force or power in them, their place is with the beasts, they are deprived of the good things life offers, good food, drink and dress. Their food is camel meat, which even the lions refuse to eat because of its bad taste. If they feed a guest they count it as a virtue, and of this, they are pound and their poets sing – they are lowly, poor and miserable and yet they are so proud and arrogant. They do not complain of hunger, poverty and misery and put themselves above all other nations. So of what are they so proud?”76 Nu’man supposedly answered, “The earth is their cradle and the sky is their ceiling, their forts are their saddles, they prefer hunger and rags to your luxury and their desert with its hot wind (sumum) to your Persian lands which they consider a prison. Allah gave them poetry which sings of their integrity (izzat), courage and loyalty. Their generosity is such that poorest among them with one camel, on which hangs his livelihood, would kill the camel for dinner for any stray guest on his door. If a criminal or an outlaw seeks refuge in an Arab tent he will be protected and defended with their life.77 Iranian disdain for the Arabs is illustrated by remarks of the commander of the Iranian army, Shirzad, on his entry to the Arab city of Anbar when the Sasanians conquered Iraq. “I saw them writing in Arabic and when I asked them who they were they said, ‘clan of Arabs settled amongst Arabs who were there before us, since the days of Negukadnessar, I was among a people who have no brains and their origin is Arab.”78 Similarly Iranian nobles had contempt towards the Sasanian king Bahram V, son of Yazdegerd I, because he was brought up at the Lakhmid court and had a taste for Arab traditions and way of life, instead of Persian manners. He spoke and wrote Arabic poetry. Nobles hindered his succession, so the Lakhmids sent ten thousand Arab soldiers who set him on the throne.79 Ahoudemmeh, a resident of Mesopotamia in the late sixth century notes about the nomads, “There were many people between the Tigris and the Euphrates who lived in tents and were barbarians and warlike; numerous were their superstitions and they were the most ignorant of all the people of the earth.”80 Iranians thought of Arabs as subservient nations and Arabs saw Iranians as bullies. The Arab-Ajam schism had arisen from Lakhmid Sasanian political marriage.

So, it is not surprising that by end of the 6th century CE Lakhmids fell out of favour with the Sasanians. Contemporary sources fail to give an accurate reason for the fallout. One guess could be Lakhmid’s increasing assertiveness towards complete independence. Other guesses could be the religious difference between the Sasanians and the Lakhmids. Iranians persuaded Arabs of Lakhmids to convert to Persian religions but failed. Sasanians saw it as disloyalty.81 Most of Lakhmid kings were pagan though most of their households were Christian. The last straw on the camel’s back could be Nu’man’s overt conversion to Nestorian Christianity.82

Anyhow, whatever the reason for the differences between the two, the Sasanians had the upper hand in this row. The last Lakhmid king, Nu’man, was assassinated by Khosrau II Parvez around 602 CE.83 A letter from Parvez, in which he justified putting N‘uman to death and ending Lakhmid rule in Hirah, claimed that “Nu’mān and his clan had conspired with the Arab tribes against us by convincing them that our empire will pass to them. I learned this information from a letter, so I killed him and appointed an ignorant Arab who knows nothing of all this to rule Hīraḥ”84

After the assassination of Nu’man, Iranians appointed Iyas bin Qabisa (Iyās bin Qabīṣah اِياس بِن قَبِيصه), a Christian, whom Khosrau II Parvez called “ignorant Arab” in the abovementioned letter. He was merely a façade for the real ruler of Hirah who was an Iranian marzban (marzbān مَرزبان of Arabic sources, marzipān of Pahlavi sources. This was the title of Sasanian governor and commander of their border provinces). People of Hirah got dissatisfied with the new rulers and were nostalgic about lakhmids. With Lakhmid buffer removed, Iranians came face to face with Arabs of the nomadic zone, who started raiding them. Chronicle of Siirt tells us that the Arabs of Lakhm revolted after this event.85 This Arab Sasanian tug of war culminated in the battle of Dhi-Qar (Dhi-Qār زى قار) around 610 CE and the defeat of the Iranian army.86, 87 After this humiliating defeat, Iranians decided to rule Hirah directly. They removed Iyas bin Qabisa and installed Iranian, Zadeeh, as governor of Hirah. Arabs of Central Arabia, loyal to the Lakhmids, seceded from Hirah during these upheavals, and so did Bahrain. The battle of Dhi-Qar actually set the stage for Qadisyah a few decades later.88 Exact location of Dhi-Qar is not known but it is mentioned in Arab chronicles.89

A war broke out between Sasanian Iran and Byzantine Rome in 603 CE. This war, also known as the last great war of antiquity, terminated in Sasanian defeat at Nineveh in 627 CE at the hands of Heraclius. Actually, it was the last battle the two superpowers ever fought. Arabs of Hirah did not participate in this campaign while Byzantine clients Ghassans took part. Muthana bin Harritha (Muthana bin Ḥāritha مَثنىٌ بِن حارِثَه) from the clan of Shayban, the hero of the battle of Dhi-Qar, was carrying out raids on the Persian frontier during the war while Iranian regular army was engaged in invading Syria.90 Arabs of Hirah took advantage of the chaos created by this war and plundered villages of Syria in 613 CE before they withdrew.91 During this war very few Arabs remained loyal to the Iranians. It is illustrated by their sporadic participation in the Roman counter-offensive of 622 to 623 CE. Even then, their loyalty was doubtful. Heraclius sent a scouting party to a site, probably in Armenia, ‘where it encountered a battalion of bearded Saracens, allies of Iran who had hoped to ambush the Roman army. The Saracen chief was captured and brought in chains before Heraclius, who pardoned him and offered him hope of command if he joined the Roman army’.92 Defeat of Nineveh in 627 CE left the Iranian army in disarray and confusion while the Arabs of Hirah grew bolder in their raids against Iranians. The Arab tribes of the nomadic zone shared this feeling with the Arabs of Iraq. In Hejaz, early Muslims in the years from 610 to 622 had sympathy for Byzantine and apathy for Sasanians.

Arab power of Ghassans

Syria (Bilād ush Shām بلادالشام), located between the northeastern portion of the Arabian Peninsula and Byzantine Rome was a replica of Iraq as far as its political situation is concerned. Like Iraq, it was inhabited by numerous Arab tribes both sedentary and nomads. And exactly like Iraqi Arabs they were unruly and used to invade settled areas of Byzantine Rome. Byzantine kings did not have any interest in extending their empire over them formally. Instead, they kept them as a buffer zone between themselves and Sasanian Iran to the east and between themselves and the Arab tribes of Northern Arabia to the south. To manage this arrangement, they used to appoint an Arab chief as ‘Phylarch’ whose duty was to keep local Arabs under control and to avert any raids of Arabs from the tribal zone or Sasanian side. Arabs of Syria were fluent in both Greek and Arabic. It is evident from a number of inscriptions written by these people in both languages. An Arabic inscription found at Nimreh near present-day Damascus mentions king Imru’ l Qays (not to be confused with the poet Imru’l Qays) who died in 328 CE and discusses the defeat of Asad and Madhij at the hands of king Imru’ l Qays who were chased away to Najran and that Imru’ l Qays was phylarch for the Romans 93 This is the earliest evidence of Arabs being phylarchs (federates) in Syria. By the 5th century an Arab tribe by name of Salihids were phylarchs appointed by the Byzantine. Then came the Ghassans.94 Ghassans were sedentary Arabs of Syria and were relatives of Aws and Khazraj tribes of Yathrib, keeping close relations with them.99 Ghassans had two capitals, Jābiya and Jalliq. Jabiya was in Golan. The location of Jalliq is not known.100

Northern gate of Sergiopolis: City was center of pilgrimage for Ghassans.101

One job of the Ghassans, like Lakhmids, was to influence tribes of Northern and Central Arabia in favour of Byzantine Rome. Jabal Usays in Syria has inscription in Arabic from 528 CE recording military expeditions by Ibrāhīm bin Mughīrah on behalf of king Ḥārith (presumably Ghassanid king Ḥārith bin Jabalah, also called Arethas by Procopius). This Ibrahim bin Mughira is identified as resident of Yathrib by Shahīd who is a world renowned scholar on the Ghassans. It means they gave employment to Arabs of central Arabia to even high ranks like general.104 A bilingual inscription written in Greek and Arabic and found at Al-Laja (nick named Harran inscription, but different from the Harran inscription of Nebonidus) mentions a military expedition onto Khaybar in 567 CE, which is considered to be that of Ghassan phylach Harith bin Jabalah to Khaybar.105 Another duty of the Ghassans was to fight against Sasanians and their allies Lakhmids along with Byzantine Rome. Jabalah bin Harith died in war of Thannūris, fighting for the Byzantine in 528 CE.106

Despite having them as allies, the Byzantine looked down upon Arabs. Whenever a contemporary Byzantine writer mentions character of an Arab, he expresses contempt for him. Theophylact Simocatta, a Byzantine historian, writing around 630 CE notes, “The Saracen tribe is known to be most unreliable and fickle, their mind is not steadfast and their judgement is not firmly grounded in prudence.”107 Similarly, Roman ambassador Commentiolus states in 566 CE, “Whenever I mention Saracens, just consider Persians – the uncouthness and untrustworthiness of the nation.”108

As time passed, the Ghassans did not remain in the good books of Byzantine kings. Ghassans were Monophysite Christians. It was a different sect from the Chalcedonian Christianity of Byzantine rulers. The Byzantine viewed the religious difference with suspicion of disloyalty on Ghassan’s part. Emperor Tiberuius II (r. 578 – 582 CE) arrested Ghassan Phylarch Mundhir bin Harith (Mundhir bin Ḥārith مَنذِر بِن حارِث, Flavios of Byzantine sources) on this ground and deported him to Sicily. Almost immediately eighty years old Ghassan Byzantine confederation began to disintegrate. Cooperation between Byzantine and the Ghasans changed into confrontation.109 Tiberius himself died in 582 CE and was succeeded by Caesar Maurice (r. 582 -602 CE). In 584 CE the new emperor met with the new Ghassan phylarch Nu’man bin Mundhir (Nu’mān bin Mundhir نُخمان بِن مَنذِر). Maurice showed his willingness to recall Mundhir, but only on the condition that Nu’man accepted Chalcedonian Christianity and campaigned with the Byzantine forces against Sasanians. The phylarch refused, and he too was arrested and sent to join his father, Mundhir in exile in Sicily. Maurice then changed the Byzantine policy towards the Arabs that was being followed since the times of Justinian I. Instead of a single unified phylarchate under Ghassans, he divided them into fifteen phylarchates.110 Though Ghassans were restored to Byzantine payroll later and played some part in Byzantine defence of Palestine against the Sasanians in 614 CE during the last war of antiquity and against Muslims in the 630s, they never gained the position they had in the second half of the sixth century.111

Relations between the Ghassans and the Lakhmids

Before we proceed to other parts of Arabia, let’s discuss briefly relations between the two Arab neighbours, the Ghassans and the Lakhmids, themselves. In addition to being proxy of their respective warring superpowers, they had their own enmities too. They had heavy hearts for each other and many a times tended to settle their account by waging a war without involving the superpowers. On one occasion, when they waged war against each other without consent of their respective principals, “Khosrau …. conferred with Mundhir [the Lakhmid king] concerning this matter [violating the treaty with the Byzantine] and commanded him to provide causes for war. So Mundhir brought against Ḥārith [the Ghassanid king] the charge that he, Ḥārith, was doing him violence in a matter of boundary lines, and he entered into conflict with him in time of peace and began to overrun the land of the Romans on this pretext. And he declared that, as for himself, he was not breaking the treaty between the Persians and the Romans, for neither of them had included him in it.”112 The dispute in this particular case was about ownership and pasturage of a territory south of city of Palmyra called Strata claimed by both sides.113

Himyar state of Yemen

South Yemen (Al-Yemen يمن) was a well-developed state.114 By 240 CE Himyar kings (Ḥimyar حِميَر) were masters of all Yemen controlling Red Sea as well as Gulf of Aden. Initially their Capital city was Zafar (Ẓafār ظفار). As Himyars grew powerful they started playing politics outside their domain. Main direction of their policy was to exert influence over the Arab tribes of central and northern Arabia and to get recognition as sovereigns from other world powers active in the area. As early as around 300 CE the Himyar king Shammar Yuhar’ish sent an envoy ‘to Malik son of ka’b, king of Azd [a tribe residing in Oman], and from there he [the envoy] undertook two further journeys, to Ctesiphon and Seleucia, the two royal cities of Persia, and he reached the land of Tanukh [a tribe in southern Iraq].115 A few decades later there was an exchange of ambassadors and the establishment of peaceful relations between Himyar and Axum.116 And about the same time the Byzantine emperor Constantius (r. 337-361 CE) ‘dispatched ambassadors, accompanied by the missionary Theophilus the Indian, to the ruler of Himyarites, seeking permission to build churches for the use of visiting Byzantine merchants and for any other who might convert to Christianity.’117 These are the earliest documented pieces of evidence of attempts on part of Himyars to get recognized by others and to gain political influence in the nomadic zone of Arabia as a sequence.

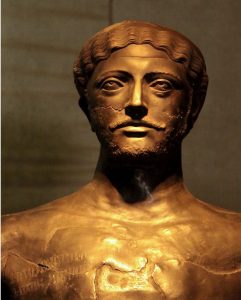

Dhamar Ali Yahbir II: Himyar king late 3rd or early 4th century CE.118

The respective sons of these leaders i.e. Abu Karb and Hujr continued this arrangement. Tabari reports ‘among those who served the Himyar king Hassan Yuha’min bin Abu Karb (Ḥassān Yha’min bin Abu Karb حَسّان يَهاءمِن بِن ابو كَرب) was ‘Amr bin Hujr, the chief of Kindah during his time. When Hassan led an expedition against the Jadis [in Yamama], he appointed ‘Amr as his deputy over certain affairs….. ‘Amr bin Hujr was a man of sound judgement and sagacity.’126 Apparently their sons after them followed suit; ‘He [the son of Hassan Yaha’min] dispatched Ḥārith bin ‘Amr bin Hujr to Ma’add and set him over them’.127 Domination of Himyars over Kindah and through them on Ma‘add was not unchallenged. Byzantine started wooing Harith bin ‘Amr, as is recounted by a certain Nonnosus, who belongs to a Byzantine diplomatic dynasty. He tells us that his grandfather had been sent to Harith son of ‘Amr son of Hujr al-Kindi by emperor Anatasius (r. 491 – 518 CE).128 Actually, Harith bin ‘Amr entered into a formal treaty with the Byzatine in 502 CE decreasing the dominance of Himyars and increasing that of Byzantine in nomadic zone of Arabia.129 The Himyar influence formally ceased to exist in 519 CE when their country became a tributary to Ethiopia (see below). In Byzantine Sasanian wars fought during Anastasius’ reign (491 – 518 CE) Kindah troops fought under Aswad in the vicinity of Nisibis along with the Byzantine magister militum Areobidus.130 Harith became most prominent of Kindah kings. In 520’s CE the Byzantine Romans declared him phylarch of Palestine.131 He extended his empire temporarily to Hirah in Lakhmid kingdom by defeating the Lakhmid rulers of the town. Iranian king Qubad acknowledged these developments and honoured Harith with the title of ‘king of Arabs’.132 It was only by 528 CE when Harith bin ‘Amr had friction with Diomedes, the silentiarius of Palestine, resulting in Harith bin ‘Amr withdrawing from Byzantine service.133 As Harith bin ‘Amr got weaker, he was expelled from Hirah in 529 CE by the lakhmids and was killed. This event practically put the Kindah state-like organization to an end. After the death of Harith the kingdom split into four fractions – Asad, Taghlib, Kinanah and Qays, each led by a prince. Byzantine kept in touch with Kindah but from a different perspective. Evidence again comes from Nonnosus who tells us that both his father Abraham and himself were sent to Qays in the time of Justinian (527 – 565 CE).134 According to Nonnonus Qays still commanded two of the most notable Arab tribes, Kindah and Ma‘add. Abraham was sent to Qays on Justinian’s orders and he made a peace treaty, under the terms of which he took Qays’ son, called Mauias [Mu’āwiyah], as a hostage and carried him off to Byzantium. Subsequently, Nonnosus negotiated with two aims; to bring Qays, if possible, to the emperor, and to reach the king of the people of Axum [Ethiopia], then Ella Asbeha, and in addition to reaching the Himyarites …. When Abraham came on another ligation on Qays, the latter went to Byzantium, dividing his own command between his brothers ‘Amr and Yazid, while he personally received from the emperor command of Palestine.”135 Imru’ l Qays (d. c. 565 CE) was a grandson of Harith ibn ‘Amr. He is the most celebrated pre-Islamic poet who tried to restore the kingdom of his forefathers.136

A wall mural from Qaryat al-Faw.137

Foreign interference in Yemen

By the beginning of the 5th century, CE superpowers were already playing a “big game” to take suzerainty of Yemen. One tool of the Byzantine-Ethiopia axis to achieve their end was to promote Christianity in Yemen and in turn produce a group of people loyal to the axis. The interest of Sasanian Iran was to keep Byzantine and Ethiopia axis at bay. Himyars themselves wished maintenance of independence. To look neutral in eyes of big powers and to distance themselves from them they accepted Judaism. Actually it was Himyar king Abu Karb As’ad who converted to Judaism around 400 CE and most of kings after him were Jews until the advent of Islam.139

Bir Hima inscription of Dhu Nawas.140

Events of the Jew king Dhu Nuwas are verified by three contemporary South Arabian inscriptions: “He [king Yousuf] destroyed the church and massacred the Ethiopians in Zafar, and waged war on [the pro-Ethiopian tribes of] Ash’ar, Rakb, Farasan and Mukha’. And he undertook the war and siege of Najran and the fortification of the chain [across the harbour at the straits] of Mandab. So he mustered troops under his own command and sent them [the chiefs loyal to him] with independent detachment. And what the king successfully took in spoils in this campaign was 12,500 slain, 11,000 captives, and 290,000 camels, oxen and sheep. This inscription was written by the lord Sharah’il the Yazanid when he was taking precautionary measures against Najran with the Hamdanid tribesmen, both townsfolk and nomads (hgr w’rb) and a striking force of Yazanites and nomads of Kindah, Murad and Madhhij, while his brother lords were with the king for the defence of the sea from the Ethiopians and were fortifying the chain of Mandab. All that they have recorded in this inscription is the way of killings, booty and precautionary measures was on a campaign, the termination of which, when they turned homeward, was in thirteen months [from its start]. [Written in] 633”. “Then he [Yusuf] sent [an envoy] to Najran in order that hostages might be exacted from them, otherwise he would wage war against them [in earnest]. But there was no surrender of hostages; on the contrary, they [the Najranites] committed criminal aggression on them [the Himyarites].146 The year given in this inscription is in the Himyar era and corresponds with 523 CE. Ethiopians were not ready to admit defeat. The next part of the story comes from a certain person Arethas [Ḥārith] narrated from the Christian perspective: “He [Ella Asbeha] collected a fleet of ships and an army and came against them, and he conquered them in battle and slew both the king [Du Nawas] and many of the Himyarites. He then set up in his stead a Christian king, a Himyarite by birth by the name Esimiphaios [Sumyafa’ Ashwa’ of South Arabian inscriptions and Aryat of Muslim sources], and after ordaining that he should pay tribute to the Ethiopians every year he returned to his home. In this Ethiopian army, many slaves and all who were readily disposed to crime were quite unwilling to follow the king back, but were left behind and remained there because of their desire for the land of the Himyarites, for it is extremely good land. These fellows at a time not long after this, in company with certain others, rose against king Esimiphaeus and put him in confinement in one of the fortresses there, and established another king over the Himyarites, Abraha (Abrāhah اَبراهَه, Abramos of Greek sources) by name. Now, this Abraha was a Christian, but a slave of a Roman citizen who was engaged in the business of shipping in the city of Adulis in Ethiopia.”147

The senior partner in the equation, Byzantine Rome was observing the situation closely. Procopius tells: “at that time, when Hellestheaeus [Ella Asbeha] was reigning over the Ethiopians and Esimiphaeus over the Himyarites, the emperor Justinian sent an ambassador Julianus, demanding that both nations on account of their community of religion should make common cause with Romans in the war against the Persians.”148

“The Puppet King” c. 530 CE.149

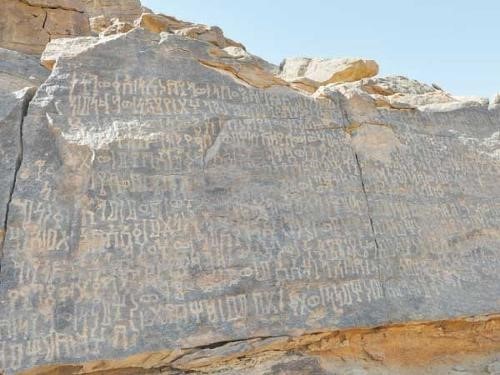

“By the power of the Merciful One (al-Rahman الرحݥن) and His Messiah, the king Abraha ……. wrote this inscription when he had raided Ma‘add in the spring razzia in the month dtbtn [April] when all the Banu ‘Amir had revolted. Now the king sent ‘BGBR [Abu Jabr] with kindites and ‘Alites and BSR [Bishr] son of HSN [Hisn] with the Sa’dites and these two commanders of the army did battle and fought [namely] the Kindite column against the Bani ‘Amir and the Muradite and Sa’dite column against …. In the valley on the TRBN [Turaba] route and they slew and made captive [the enemy] and took satisfactory booty. The king, on the other hand, did battle at Haliban and the [troops] of Ma‘add were defeated and forced to give hostages. After all this ‘Amr son of al-Mundhir [the Lakhmids] negotiated with Abraha and agreed to five hostages to Abraha from al-Mundhir, for al-Mundhir had invested him [‘Amr] with the governorship over Ma‘add. So Abraha returned from Haliban by the power of the Merciful one …..in the year 662.” 152

Abraha’s Mughiran inscription. 153

In any case, Ibn Ishaq alleges that during the expedition of elephant Abraha threatened to attack the Ka’ba in Mecca but actually failed to do so.158 Ma’mar asserts that during the threat all Quraysh escaped the town except Abdul Muttalib (‘Abd ul Muṭṭalib عَبدالمُطَّلِب) who stayed there.159 Early Islamic sources report that Abraha died on the way back to Yemen.160 According to Kister’s analysis this event took place in 552 CE131 while according to Robin’s analysis it should be dated to shortly after 558 CE.161

Yemen loses independence

So we can see that the nomadic zone of central and northern Arabia that was dominated by Lakhmids since defeating of Kindah king Harith bin ‘Amr at their hand in 529 CE, once again became a sphere of Yemeni influence under Abraha and remained so for almost a decade. Abraha was succeeded by his son Yaksum and on Yaksum’s death Abraha’s other son Masruq took over, according to early Arabic sources.162 But in Abraha’s Marib dam inscription he was succeeded by his brother Masruq. What happened exactly to Yemen after the death of Abraha is a mystery. According to ibn Ishaq time span from the advent of Aryat, which is known to be 525 CE, to the death of Masruq was 72 years.163 Thus year of Masruq’s death can be calculated to 597 CE, thirty-nine years after death of Abraha. Historic sources are silent about this period.164 Apparently Ethiopia’s involvement and influence in Yemen, which Abraha had contained temporarily, grew again. When Yemenis got convinced that they could not maintain their independence they chose to be vessels of Sasanians. “When the people of Yemen had long endured oppression, Sayf ibn Dhi Yazan the Himyarite went …. To Nu’mān ibn Mundhir, who …. Took him with him and introduced him to Khosrau ….. when Sayf Ibn Dhi Yazan entered his presence he fell to his knees and said, ‘O king, ravens [meaning the Ethiopians] have taken possession of our country … and I have come to you for help and that you may assume the kingship of my country’ …. So Khosrau sent [to fight the Ethiopians] those who were confined in his prisons to the number of 800 men. He put in command of them a man called Wahriz who was of mature age and of excellent family and lineage. They set out in eight ships, two of which foundered so that only six reached the shores of Aden. Sayf met Wahriz with all the people that he could muster, saying, ‘My foot is with your foot, we die or conquer together’. ‘right!’ said Wahriz. Masruq ibn Abraha, the king of Yemen, came out against him with his army …. Wahriz bent his bow – (the story goes that it was so tough that no one but he could bend it) – and ordered that his eyebrows be fastened back. Then he shot Masruq and split the ruby in his forehead, and the arrow pierced his head and came out at the back of his neck. He fell off his mount and the Ethiopians gathered around him. When the Persians fell upon them, they fled and were killed as they bolted in all directions. Wahriz advanced to enter Sana’a, and when he reached its gate he said that his standard should never be lowered.”165 This story gives us a clue that Khosrau II Parvez was not interested in annexing Yemen. He sent criminals to fight instead of his regular army. That is the reason Sayf was made king on the understanding that he would remit taxes to Khosrau every year and Wahriz returned to Iran. However, conspiracies of opposition continued. Sayf was stabbed to death by a group of Ethiopian servants and Khosrau dispatched Wahriz once more, this time to bring Yemen under direct Iranian rule.166 According to Ibn Ishaq, Khosrau appointed his son marzban ruler of Yemen at the death of Wahriz. When the marzaban died Khosrau appointed his son Taynujān [Baynujān in Tabari] over Yemen. He was succeeded by his son but he was deposed to be replaced by Badhan (Bādhān باذان).167 Yemen remained under the direct rule of the Sasanians until the early Muslim state took charge. Actually, Yemen converted to Islam before the ‘conquest of Mecca’ and years before any Muslim army reached here. Following the death of Khosrau II Parvez in 628 CE, the Iranian marzban Badhan converted to Islam.

Final deterioration of Nomadic Zone

Thirty-nine or so years between the death of Abraha and the death of Masruq are critical for the nomadic zone of Arabia. We hear of Ma‘add for the last time in conjunction with the conquests of Abraha. This big and influential confederation of the nomadic zone of Arabia might have disintegrated during those thirty-nine years. Lakhmids had filled the political vacuum in the nomadic zone that Abraha’s death had generated. We do not hear of Lakhmid’s authority over a big tribal confederation during this period. The Lakhmids established their authority on individual tribes based on mutual agreements. The Lakhmid’s fall from power in 602 CE might have spurred the process of political disintegration in the nomadic zone that was already underway. This was the political situation of the nomadic zone when Islam appeared in 610 CE and started spreading.

Oman

Yemen’s neighbouring land Oman was dominated by Azd (أزد) tribes in the pre-Islamic era. They were led by Julada princes. Archaeological evidence points to Sasanian influence or their presence in the area just before the advent of Islam. The Azd and the Sasanians were at daggers drawn. Their struggle entered into a final phase when Prophet Muhammad sent a military campaign from Yathrib with whom Azd cooperated well. They both routed Sasanians out of Oman in 630 CE, killing Maska, the Sasanian administrator in Oman.168

Bahrain

Bahrain (Al-Baḥrayn البحرين) consisted of the lowland in the eastern portion of the Arabian Peninsula on the shores of the Persian Gulf. Being in the vicinity of Sasanian Iran, it had always been under its influence. On occasions, it was ruled directly from Ctesiphon as Tabari reports that Khosrau I Nawshirwan’s governor in Bahrain was Azadhfiruz son of Guianas. He was asked to punish Tamim whose clan Yargu’ had plundered a caravan and Hawdha ibn ‘Ali al Hanafi [king of Yamama] had complained about it to Khosrau.169 On other occasions local chiefs ruled the Arab tribes in the name of the Sasanian king in the seventh century CE.170 We don’t hear of any influence of Himyars through Kindah or of Abraha on Bahrain. Probably it remained under Sasanid influence either directly or through their clients Lakhmids. As mentioned earlier, it drifted away from the Lakhmids by the eve of Islam after the death of Khosrau II Parvez in 628 CE.

Yamama

Yamama (اليمامه Al Yamamah) occupied the central plateau of Nejd. It had its own state-like entity on the eve of Islam. Yamama was left deserted after the defeat of Tasm and Judais at the hands of Hassan Yuha’min bin Abi Karb Tubba’, the Himyar king. Then Banu Hanifa started inhabiting Yamama. As they settled they gradually became sedentary.171 Ultimately they became the largest sedentary tribe in Yamama in the decades preceding Islam.172 Defeat of Harith bin ‘Amr, the Kindah king, in 529 CE at the hands of the Lakhmids produced a political vacuum in Yamama. The clans of Hanifa started managing their affairs by establishing a council of four outstanding figures (ashrāf اشراف) from three clans of Hanifa. The council’s tenure did not last long. Hostilities erupted between Hanifa and Tamim. It affected Yamama’s economy and resulted in collapse of the council.173 Battle of Nuta’ was the final armed confrontation between Tamim and Hanifa, in which the latter were successful.174 It started after Tamim attacked Iranian caravans which were unsuccessfully defended by Hawdha bin Ali, the new leader of Hanifa, who had contracted allegiance with the Sasanians. Despite initial failures, Hawdha showed determination and remained loyal to the Sasanians. Ultimately, with their help, he won the war of Nuta’. It was the beginning of Hawdha, who gradually emerged as a single leader of Yamama.175 As Hawdha had complained to Khosrau I Nawshirwan about Tamim’s involvement in the plunder of caravan and that Khosrau ruled up to 579 CE, it can be assumed that Nuta’ was fought before 579 CE. In early period of their political strength, Hanifa’s capital city was Hajar.176 Hawdha changed the capital to his hometown Jawa or Jaw al-Khadhram. He managed to stand firmly against ‘Amr bin Hind, the Lakhmid king who once penetrated into Yamama. Lakhmid defeat by Hanifa is recorded by contemporary poet al- A’sha.177 Though Hawdha could repel Lakhmid influence at the time when they were penetrating in other parts of the nomadic zone and later that of Abraha, Hawdha was not an independent sovereign. To maintain his political hegemony over his opponents he had to make a political bridge with Sasanians. It was Khosrau I Nawshirvan, the Sasanian king, who awarded him a crown and named him king of Yamama.178 Tabari reports that an Iranian protector was stationed in Yamama till the death of Hawdha. Tabari also reports that Yamama was controlled by the Iranian agent Mundhir bin Nu’mān, ruler of Hirah. Tabari further reports that a Sasanian king is said to have waged a raid in the Arabian Peninsula to establish a secure station to patrol the trade routes. Such reports confirm Sasanian influence. Once, Khosrau wrote to Hawdha to arrange his meeting with ‘Abd Allah bin Jad’an, a high dignitary in Mecca. This report gives a clue that Khosrau was going to utilize Hawdha to extend his influence up to Mecca. However, the meeting did not take place.179 Tamim, the main opponents to Hawdha’s authority, entered into a confederation with other tribes living around Yamama, like Qays and ‘Aylan (عَيلان). Tamim also developed good relations with the Lakhmids and Mecca. Therefore, Tamim remained in a position to employ pressure on Hanifa and their government.180 Hanifa generally liked Hawdha’s leadership but there was opposition against any Iranian penetration and the presence of any Iranian protector.181 To strengthen the economy of Yamama, Hawdha exchanged commercial envoys to Yemen and Bahrain and tradesmen from these areas were encouraged to settle in Yamama.182

Two significant events took place near the end of Hawdha’s fifty years long tenure. One was the defeat of the Sasanians at the hands of Byzantines in the last war of antiquity and the second was the advent of Islam. It was he whom Prophet Muhammad considered the king of Yamama and to whom he wrote a letter inviting him to Islam.183 Hawdha did not switch his allegiance from the Sasanians to Islam. He was willing to accept Islam provided Prophet Muhammad would give him a position in the Islamic government and assure him of the independence of Yamama.184 Around 630 CE Hanifa tried to revive al-Lahazim confederation under the threat of Islam.185 Anyhow, Hawdha died before any confrontation with the Islamic army and it was his heir, Musaylima who faced the swords of Islamic fighters.186

Northern Hejaz

Now we divert our attention to what was going on in Yathrib (Yethrib يثرب), a town or probably congregation of adjacent localities, which was destined to be the first capital of the Islamic state and was later called Medina (Madīnah مدينه). The dominant political group of Yathrib before Islam was Jews. Their tribes Banu Nadir (Naḍīr نَضِر) and Banu Qurayza (Qurayẓa قُرَيظَه) are described as ‘kings’ (mulūk ملوک) over Medina, ruling the Banu Aws and Banu Khazraj, who were mainly pagan Arab tribes.187 Nadir and Qurayza both did not have the guts to rule over Aws and Khazraj on their own. They had to secure support from one of the superpowers of the time. They chose Sasanians, as Jews were never on good terms with the Christian Byzantine. This assertion is strengthened by Muslim tradition that Ibn Ra’s al-Jalut, (literally meaning the son of the exilarch) was present in Medina at the time of Muslim immigration to Medina. His name was Bustanay and he discussed with the Prophet the matter of the names of the stars in Joseph’s dream. Exilarchs were Jews who were exiled from Palestine, their homeland, by the Byzantine. The presence of such a person in Medina proves that Byzantine Rome did not have any influence over Medina at that time.188

Ibn Sa’id mentions in his Aswal al-Tarab that ‘Amr bin Itnaba was appointed by Nu’man (Lakhmid king) as king of Medina. His name as the king of Medina has been mentioned in other sources as well. By looking at other names with whom he interacted, his era has been guessed to be the second part of the sixth century CE.189 This era coincides with an increase of Lakhmid power over the nomadic zone of Arabia after the death of Abraha. Ibn Hurdadbeh in his kitāb al-Masālik wal-Mamālik records a tradition according to which the marzban al-Badiya appointed an ‘amil on Madina, who collected the taxes.190 The Qurayza and the Nadir, this tradition says, were kings who were appointed by the Sasanians on Medina, upon the Aws and the Khazraj. A verse to this effect by an Ansāri poet is quoted in the tradition: ‘you pay the tax after the tax of Kisra; and the tax of Qurayẓa and Naḍīr’. Iranian suzerainty, based on the Jews of Medina, would have been strengthened by the initial Sasanian victory over Byzantine in the last war of antiquity.191 Jew’s absolute dominance over Arabs started eroding as Sasanian Iran got weak. We shall discuss it later.

Here, it won’t be out of order to discuss the presence of Jews in, around and north of Yathrib as a political entity. The presence of big Jewish populations in settlements of North Arabia, like Khaybar, Tayma and Fidak etc. has been attested by early Muslim sources.192 Talmudic sources agree with them in describing a Jewish population which inhabited the south-eastern parts of Palestine (inclusive of Transjordan). Jericho, So’ar, Eylat and their surroundings formed the northern edge of this Jewish area, which stretched into the Arabian Peninsula, starting from Wādi ‘l Qura, which, according to Muslim traditions represented the border between Hejaz and Syria and reaching the city of Yathrib.193 Jews of Hejaz appear to be a unique ethnic group, different from the Jews of Southern Arabia.194 Their origin is puzzling. Gil suggests that they might be political asylum seekers in face of persecution by Byzantine authorities in Palestine, most probably in 70 AD and perhaps also in 135 AD. Scattered Jewish families had been living in Arabia. This wave of refugees might have produced a substantial population in Hejaz. During the centuries that followed they increased in number with the addition of Arab tribes who converted, and adopted an agricultural life, taking over not only the Jews’ religion and way of life but also their spoken language, Aramaic.195 An inscription published by Altheim and Stiehl, from a photograph taken in 1965 at Madain Saleh is engraved on the tomb erected by ‘Adnun son of Ḥūnī (or Ḥunnay) son of Shemūel resident of Ḥigrā for his wife Mūnā, daughter of ‘Amru son of ‘Adnūn son of Shemūel resident of Tayma. She died in Av 251 at the age of 38. Here leading figures of two localities are mentioned, Ḥijr and Tayma, both named Samuel. This inscription dates from 319 CE, if the counting begins with 68, reckoned as the year of the destruction of the temple and common in Jewish inscriptions; or from 356 CE, if counting starts from 105 when Provincia Arabia was founded by emperor Trajan.196 This kind of historical clue suggests that Jews were well-established in Hejaz by the 4th century CE.

Like their origin, the ethnicity of north Arabian Jews is controversial as well. Nau thinks that Hejazi Jews were Arabs as almost all Jews mentioned during the Prophet’s lifetime had Arab names.197 Similarly, their immense contribution to Arabic Poetry convinces Noldeke that the Jews of Hejaz were Arabs.198 But Waqidi claims that Nadir and Qurayza were original Jews, from the children of the Kāhin of the Banu Hārūn.199 Isfahani was skeptical about the genealogies of Nadir, Qurayza a and Qaynuqa. He declares not having found any genealogy of the above, ‘since they were not Arabs, whereas the Arabs used to record their genealogies; they were only allies (hulafa) of Arabs.200 There is evidence that at least some of the Jews living in Yathrib were actually Arabs. Suhayli informs us that besides Qurayza, Nadir, and Qaynuqa, there were people of Aws and Khazraj who became Jewish (mantahawwada).201 It is possible that the initial population was ethnic Jews but it thinned out and Arabised as local Arab tribesmen joined ranks with them by conversion.

These Jews had a language of their own that was different from Arabic. Muslim sources call it by many different names. Waqidi calls this language ‘Yahudiyya’.202 Ibn Athir calls this ‘Ratan’.203 Tabari says it was Persian.204 Jewish language was written in a different way from Arabic. When Muhammad bin Maslama won the sword of Marḥab after killing him, something was engraved on it. Nobody knew how to read it until one Jew from Tayma read it ‘This is the sword of Marḥab. Whoever tastes it will die’.205 Epigraphic evidence of Arabian languages is very strong but no inscriptions have been found written in such languages. Gil believes the Jewish language was Aramaic.206 It is still plausible that some Jews, who emigrated from other areas, adapted Arabic while maintaining their original language as well. At the same time, Arab converts spoke only Arabic.

Politics of Mecca

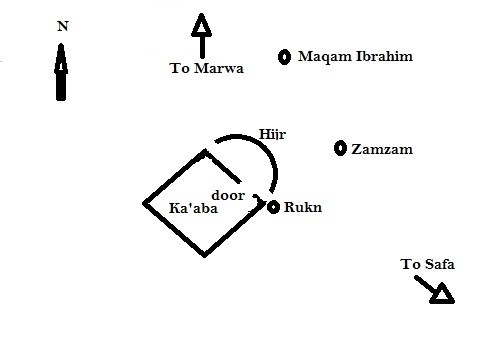

After a brief survey of politics and political role players of Arabia on the eve of Islam, let’s now concentrate on Mecca (Makkah مكّه) itself, the cradle of Islam. Before we go into details of politics at Mecca, let’s understand one socio-political term of pre-Islamic Arabia – Haram (Ḥaram حرم). In pre-Islamic inscriptions, the word mahram is used in associated with shrines and is generally rendered as ‘temple’. It still survives in the name of ‘Mahram Bilqis’ the Sabaean temple at Ma’rib, in Yemen. Timna, the capital of Qataban, the ancient Yemeni state, had a mahram dedicated to the god Dhu Samawi. The inscription identifying it refers to a maḥram and mnsbt, the latter meaning a place of ansab or boundary of stones for a harem such as we know used to exist in the Ka’ba at Mecca. Word ḥaram is derived from maḥram.207

Dinār: Currency of pre-Islamic Mecca. 208

Early Islamic sources report many other temples that were reverenced like Ka’ba. Those temples are not clearly mentioned to be haram but one can assume that there could be haram around them. For example, Ibn Ishaq reports that there was a temple by name of Ṭawāghīt, which Arabs venerated like Ka’ba. They used to circumambulate it and offer sacrifices there. This temple had its own guardians and overseers.212 Himyar had a temple in Sana’a (Ṣan’ā’ صَنَعَاء) by name of Ri’ām.213 Similarly, Ruḍāa’ was a temple run by Rabī’ā clan of Tamim.214

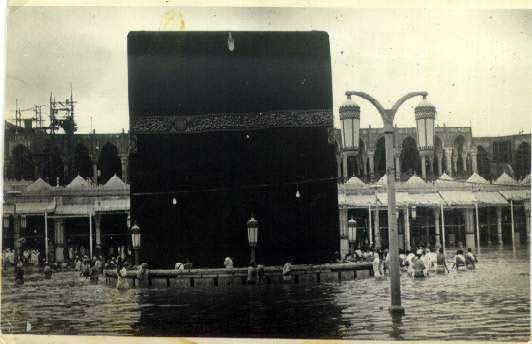

Mecca’s ancient history is obscure. We do not know exactly when it came into existence. What we know more definitely is that this place did not cultivate anything and depended upon trade and religious pilgrimage for survival.215 Early Islamic sources link the construction of the Ka’ba with Ibrāhīm, the biblical Abraham.216 When reporting of actual political events begins, it was Jurhum (جُرهُم) tribe who was in charge of Ka’ba. This prompts some scholars to speculate that it could be Jurhum who built Ka’ba. Ibn Ishaq informs us that Jurhum were immigrants from Yamen and their only reason to settle in Mecca was an abundance of water and trees.217 One can infer from this tradition that Mecca already existed when Jurhum reached there. Later on, Bakr bin ‘Abd Manāt clan of Banu Kinanah (Kinānah كِنا نَه) and Ghubshān clan of Banu Khuza’ah (Khuzā’ah خُزاعَه) joined hands to defeat Jurhum in open war and expelled them from Mecca. Out of the two victors, it was Khuza’ah who got control of Ka’ba. This is the time when Quraysh appear on the scene under their leader Qusayy bin kilab (Quṣayy bin Kilāb قُصَى بِن كِلاب). Qusayy fought an open war with Khuza’ah and their allies Bakr bin ‘Abdu Manat of Kinanah. Another part of the tribe of Kananah was allied to Quraysh, verifying the hypothesis discussed above that it was the clan and not the tribe that was politically sovereign. Though the war was indecisive, Quraysh expelled Khuza’ah and Bakr bin ‘Abu Manat from Mecca as a result of the judgement of a post-war arbiter. This is how Qusayy eventually took over Ka’ba’s cultic office.218 As Qusayy bin Kilab was the 5th generation forefather of Prophet Muhammad and Prophet Muhammad was born in the second half of 6th century, it can be calculated that this event would have taken place in the second half of the 5th century CE.219

Qusayy appears to be the most significant leader and statesman in the pre-Islamic history of Mecca. He is credited to be a unifier (mudhammi’) who organized the tribal union of the Quraysh and brought them from their dwellings to the settlement of Mecca.220 He behaved as a king over his tribe and the people of Mecca.221 Ibn Ishaq and Ibn Sa’d both mention that he cut trees in the haram district to renovate the periphery of the haram district.222 Cutting trees in haram is considered a crime in early Islamic traditions. Apparently, Qusayy got immunity from his fellow tribesmen. He performed both cultic (hidhaba) and political (siyada) functions over Ka’ba. He established the institution of siqaya (that the Quraysh would provide water to pilgrims and probably to their animals) and rifada (that the Quraysh would provide food to the pilgrims).223 Ibn Ishaq reports that the Quraysh used to provide food to pilgrims.224 Siqaya and Rifada helped Qusayy attain total control of the management of the pilgrimage. Azraqi has also described the ritual of lot-casting with arrows.225 As this function was linked to the priest’s office, Qusayy also acted as judge (sahib al-qidah). Al-Fasi reports another privilege of the Quraysh. They performed official duties of arbitration on the basis of the ‘Qasama’ and in return for which they were paid a hundred camels per man.226

Qusayy might have presided over Qasama ceremony.227 Azraqi and Ibn Ishaq both report that Qusayy founded an assembly house, Dār al-Nadwah (دارالندوه) which was used for consulting Quraysh, and only a Quraysh who had crossed forty years of age was allowed in such consultations.228 Dar al-Nadwa was also used for conducting ceremonies that had to do with the rites des passages; entering into a marriage contract, performing circumcision on young boys and carrying out ceremonies for girls upon reaching puberty who were declared marriageable, received a dir (a shift like a dress) and were finally led into the house of their parents. On the occasion of initiation ceremonies, ritual banquets (I’dhar/’adhir/’adhira) were also celebrated.229 Qusayy kept Liwa, the banner of war in Dar al-Nadwa and had a right to declare war. In this regard, he must have been, of course, dependent on the assembly of noblemen (mala). He was the supreme commander of the military (qiyada). According to al-Hufi three war banners were kept in the Dar al-Nadwa, one for the Kinanah, another for the Ahabbish (Aḥābīsh اَحابِيش) and a third for the Quraysh. The Ka’ba was considered property of a divinity; Qusayy acted as its administrator and hence had access to the supernatural.230 Furthermore, it should not go unmentioned that Qusayy unified Quraysh on behalf of Allah. Azraqi mentions ‘abuhum Quṣayyu kana yud’a mudjammi’an bi-hi djama’a Allahu al-qaba’ila min Fihri’, meaning their father Qusayy is called the unifier, through him Allah has united the tribes of Fihr.231 Fihr is the fictitious ancestor of the Quraysh. Similar passages are written by Ibn Ishaq and ibn Sa’d.232 Hence we can see Qusayy converted Mecca into a state-like tribal entity. This entity remained neutral from the superpowers of the time up till the advent of Islam, though it underwent deterioration in terms of leadership and reduced to mutually conflicting clans.

Over time the spiritual and political combined chieftainship of Qusayy underwent a radical structural change. Political leadership ultimately rendered itself independent of cultic offices. In this process Meccan political organization became dynastic. It was contrary to general Arab rule of a succession of chieftainship that was qu’dud. The hereditary way of succession could have developed under influence of the states existing in Arabia at that time.233 There are two versions of how it took place. According to the first version, passed onto us by Ibn Ishaq, Qusayy’s eldest son, Abdul Dar (‘Abd al-Dār عَبد الدار), assumed all functions of Qusayy and bequeathed them to his agnates. Abd Manaf (‘Abd Manāf عَبد مَناف), who was the more prominent son of Qusayy didn’t get any of the functions. Later on ‘Amir bin Hāshim bin Abd Manaf bin Qusayy, who belonged to the 4th descending generation of Qusayy, contested these privileges from agnates of Abdul Dar.

Dirham used in pre – Islamic Mecca. 234

In this arrangement, Abdul Dar had a right to declare war but Abd Manaf was the commander of the army. All important offices in the Abdul Dar segment were bequeathed. The functions of Abd Manaf were, on the other hand, distributed among his agnates in the following manner. Qiyada was assumed by his son Abd Shams (‘Abd ul Shams عَبدُ الشَمس), siqaya and rifada was consigned to his brother Hashim, the great-grandfather of Prophet Muhammad. 236, 237 Duties of rifada and siqaya ultimately fell on the shoulders of Abdul Muttalib bin Hashim (‘Abd ul Muṭṭalib bin Hāshim عَبدُالمُطَّلِب بِن هاشِم).238

The friction that developed between two branches of Banu Qusayy and as a result of which combined offices separated and one group became muṭayyabūn and the other ahlāf was of political importance. Both groups had even separate cemeteries in Mecca.239, 240 It was this development after which the Abd Manaf group, which was deprived of cultic functions, was free to devote itself more intensively to the development of foreign commercial relations.241, 242 In 561 CE the Byzantine and the Sasanians entered into a peace treaty.243 Paragraph five of this treaty dealt with duty payments on goods brought in by Arab merchants. They could enter Byzantine Rome only through the border post of Daras and into Sasanian Iran through Nisibis. This regulation of controlling goods coming from Arabia was adhered to by the two great powers even when they were involved in conflicts. It shifted the Mesopotamian trade route towards northwest Arabia, a route that the Meccans, by virtue of the geographic location of their settlement, could easily find access to. And this regulation formed a prerequisite of any future settlement that Quraysh could enter into with representatives of both governments.244 Hashim, being relieved of the cultic offices of the Ka’ba and well-positioned to enter into a trade, was the first to conclude such a treaty (‘ahd عهد) with the representatives of the Byzantine government in Syria. His brother Abd Shams made such arrangements with the government authorities in Sasanian Mesopotamia, Yemen and Ethiopia.245

Meccan society was a tribal class society, very dissimilar from a capitalistic class society. Tribal-based social stratification in Meccan society was more profound than economic stratification. The exact details of stratification are not known due to a lack of sources. Probably it had four classes; tribes of equivalent descent, clientele groups whose descent was not always clear, certain craftsmen and slaves. The ruling class established its social status, on the one hand, through the ideology of heredity (genealogy) and on the other, by the right of disposal and control over the most important means of production (land, cattle and commercial capital). They claimed political self-determination. The less privileged classes were further organized hierarchically according to their birth and professional specialization. The political right of self-determination was refused to them. They were under the protection of the ruling class on the basis of jiwar relations.246 The less privileged groups were excluded from participating in consultations in the Dar al-Nadwa. It is still not clear what social status did free slaves have.

The practice of redistribution of wealth to the poor was considered piety and a mean of enhancing one’s honour and hence it was a matter of social prestige.247 Appearance of commercial capital in one branch of Banu Qusayy resulted in wealth differences among Meccans. The wealthier were able to redistribute to the poorer segment. It is described as a positive trait of the Prophet’s kin group by early Muslim sources. Dostal suggests that this custom, which was already present in the Prophet’s family, would have continued as zakat (zakāt زکۈة).248 Three types of poor groups are known; ta’if ‘l-khula‘a, meaning the outcasts; ta’ifa ‘l-aghraba, meaning probably bastards and ta’ifa ‘l-sa’alik al-fuqara, beggars.249