Economists believe that in any given region, the most basic economic activity is the production of food, clothing and shelter. Such economic activities are a prerequisite for the permanent inhabitation of any region. They are the primary economic sectors. Then, humans attend to exploit the natural resources of the area. They develop industries like forestry and mining. At the same time trade develops. The service sector with specialized tradesmen, like bakers, cooks, barbers, drivers, physicians, nurses, and teachers, spring up in society. All such industries are secondary economic sectors. As prosperity continues, society generates tertiary industries, like the entertainment sector, manufacturing of luxury goods, long-haul transport etc. The combined efforts of archaeologists and historians have established beyond doubt that pre-Islamic Arabia had a well-developed economy with primary, secondary and tertiary economic sectors.

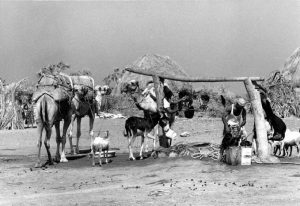

Nomadic pastoralism

Sheep grazing: Arabia

The most basic economic activity practiced all over Arabia was Nomadic pastoralism. The arid environment of Arabia favoured grazing as opposed to the cultivation of crops and raising farm animals. This activity was practiced in Arabia for millennia.1 The most desirable animal to raise by grazing was the camel.2 A camel was an ideal grazer in semi-desert conditions. It walks long distances at a faster speed, can live without water for long and can carry more load than any other grazer. These qualities enabled camel grazers to explore farther and more arid areas for grazing and to remain there for longer.3

Nomadic pastoralism was not limited to camels, in any case. Goats and sheep were raised as well.4 Nomadic pastoralism provided the society with meat, dairy products, hides and articles made up of hides like tents and wool etc.5 It has also been postulated that Arabs sold camels to foreign countries like Sasanian Iran to be used in caravans travelling from India and China to Europe. Grazing was done mainly by nomads as opposed to the sedentary population.6

The camel was such a valuable commodity that it had become a kind of currency. We hear of dowry and blood money being paid in terms of a number of camels. We also hear of estimates of the personal wealth of a person by counting the number of camels he possessed. Amr bin Hisham (‘Amr bin Hishām عَمرو بِن هِشام, early Islamic sources call him Abū Jahl ابُو جهل) bought one camel for three hundred dirhams on the eve of the battle of Badr.7 It gives us an idea of the price of a camel.

Horses too were raised in Arabia. Horses appeared in Arabia about one or two centuries before Islam. Their main use was in the cavalry. Horses had to be raised in areas where the grass was abundant and water was readily available. Arabs used to reserve such lands for horse raising only. Such areas were called ḥima. Golan was the main region of horse grazing for the Ghassans but himas were spread all over Hejaz and Nejd.

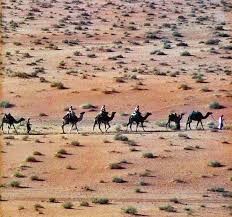

Camel grazing in Arabia

One such hima was al-Rabda, which existed from the pre-Islamic era but was developed further by Caliph ‘Umar and had the capacity to raise forty thousand horses.8, [The locality of Rabda got fame later because Abu dhar Ghifāri resided here during his exile. Saudi archaeologists have excavated it. (Christian Julien Robin, Roads of Arabia ed. ‘Ali ibn Ibrāhīm Ghabbān, Beatrice Andre-Salvini Francoise Demange, Carine Juvin and Marianne Cotty, (Paris: Louvre, 2010).[/note] The horse raised in hima was of a noble breed that had proved its usefulness in Byzantine-Sassanian wars and was destined to be later known as the legendary Arabian horse during the early Islamic centuries.9 One war horse sold for three hundred Dirhams.10 Isfahani tells its price in Dinārs to be a hundred Dinārs.11

Agriculture

Agricultural field in desert: Arabia

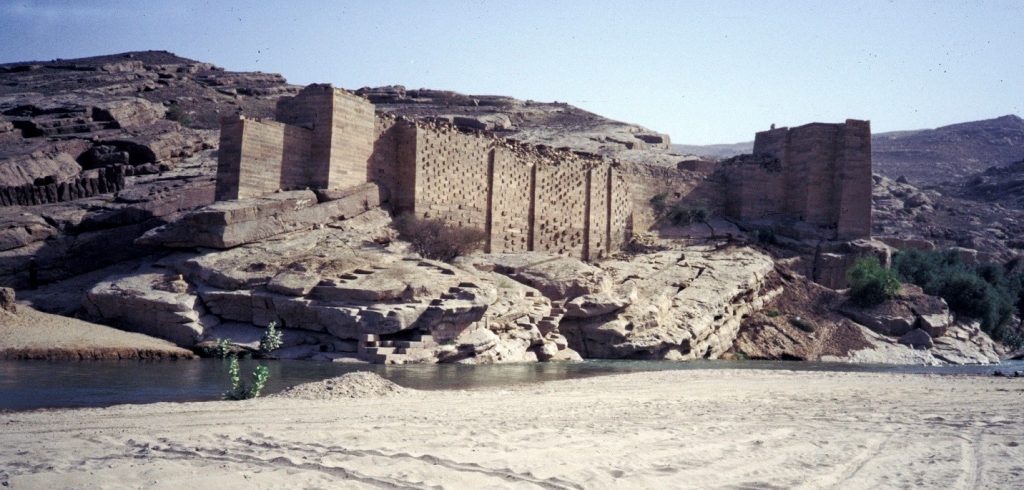

The next most prominent industry was agriculture. Arabian Peninsula had fertile lands with the availability of water in many areas. Cultivation first developed in such lands. Syrian steppe, called Fertile Crescent by archaeologists specializing in the debut of humanity, was actually the cradle of agriculture. During the pre-Islamic centuries, Syria was a fully-fledged agricultural country, thanks to the dams and irrigation system built by the Ghassans.12

Iraq, especially its al-Jazirah part, was a grain basket for the whole region. 13

Yemen, known for its terrace farming and huge dams since antiquity, was not less than any other country as far as agriculture is concerned. 14

Though arid desert conditions precluded most of mainland Arabia from crop cultivation, amazingly, pockets of agricultural land were present wherever water was available. Dams and other irrigation structures discovered by archaeologists and belonging to the centuries before Islam provide ample proof of advanced agricultural practice in Hejaz and Nejd.15 These oases not only supported the growth of date palms but also cereals like wheat, barley, legumes and even fruit.16

Well in Tihamah: Pre – oil Arabia

Date stones were also utilized in some way but the details are not known. 17 Date crop of Khaybar was eighty thousand barrels.18 Katība alone (a fortress in Khaybar) used to produce eight thousand barrels of dates and three thousand measures of barley.19

Arabs used to contain flood water and distribute this water to agricultural fields.20 They had also built underground aqueducts similar to the Qantas of Iran. Their construction needed bridging of obstacles and for that purpose use of cement.

Arabs had learned this technique from Iranians and Romans. 21 This system was definitely present in Oman and also probably in Yamama.22 Yathrib itself was a widespread oasis consisting of many villages.23 Discovery of numerous dams around Taif by archaeologists, for example, Samallaqi dam, verifies the agricultural past of this region.24

Yamama was such an agricultural land that its economy was independent of grazing. Yamama even produced pomegranate, potash or saltwort (ushnan) and sugar.25 Same is true for Taif which produced pomegranates and plums.26. Products made out of Asclepias procera were popular all over Arab.27

In addition to the conventional crops, pre-Islamic agriculture had ventured into more sophisticated agricultural products. Beekeeping and honey production was a large-scale business in Taif.28

While the wine growing and fermenting industry of Syria is well known, it is surprising that it was also practiced in Taif.29 Brewing from the juice of dates was almost a cottage industry. Such breweries were located inside commoners’ homes.30 Arabs of Yamama produced date wine by hollowing out palm tree trunks and filling it up with freshly squeezed dates or squash.31 Extent and scale of agriculture can be imagined from the fact that when Caliph Mu’āwiyah became the owner of a farm in Jaw al-Khadharim (in Yamama) he employed forty thousand slaves to work.32

A question still unanswered by research is whether the raising of livestock by the nomads far from agricultural areas made agricultural land infertile due to a lack of manure.33 Irrigated agricultural land and water resources were privately owned.34 However, the less productive rain agricultural land was common property.35 Water ownership was separate from land ownership and was more valuable.36 Many free farm workers, as opposed to slaves, called mawali working in Yamama were Persians.37

Ruins of great Maʾrib Dam: Yemen. 38

As discussed earlier Mecca was not suitable for cultivation. 42 It had to depend on another kind of economic activity mentioned later in this text.

Natural resources-based industries

Pre- Islamic Arab economy was exploiting each possible venue of natural resource usage. Fishing was an economic base in many villages and towns located near the sea. Archaeologists have discovered many such locations, especially on the east coast. Jubail and Tarout are examples of such sites.43 Pearling was a high-value industry at fishing locations.

Manufacturing

The manufacturing industry accounted for a good part of the total wealth generated by the Arabs. Arabs used to tan leather and make leather goods from it like garments, buckets, pipes which could supply water at a distance and other articles of daily use.44 Leather was plastic of the time and used in almost everything.45

Women weaving at home;

Pre – oil Arabia

As expected, Arabs were self-sufficient in textiles. Weaving was a household cottage industry. Tharmeda, a place in Yamama, was famous for textiles.46 Murat and Ramada made the best fabrics in Arab.47

Metallurgy was not lagging behind any other branch of manufacturing. Arabs used to make swords, knife blades, arrowheads, spearheads and iron ploughs.48 Balad, a location in Yamama, was particularly famous for making swords.49 Samhudi informs that there were more than three hundred jewellery smiths in the Yathrib suburbs of al-Zuhrah alone.50

Mining

About 300 km northeast of Mecca is a famous gold and silver mine by name of Mahd adh Dhahab. Radiocarbon studies of its tilling, the refuse from ore processing, has established that this mine was active from c. 430 CE to 830 CE, all the years coinciding with pre-Islamic and early Islamic eras.51

Numerous stone dwelling ruins resembling barrack-like structures found near the mine suggest that a large workforce was employed at the mine.52 It has been guesstimated by archaeologists that about thirty tons of gold was extracted from this mine in ancient times. It is worth 1.2 billion US dollars at 2008 rates.53 This archaeological evidence is supported by traditions recorded by early Islamic sources about gold and silver mining in pre-Islamic and early Islamic periods. Actually, about two hundred mines are mentioned by Islamic sources in the area. It is congruent with about one thousand mining sites that have been discovered in West Arabia alone which were active in pre-Islamic and early Islamic times.54 Mahd adh Dhahab has been identified with a mine that Isfahani reports being owned by Banu Sulaym.55

It is now an established fact that the mining of precious metals was the backbone of the pre-Islamic Arab economy. Mining of precious metals was not limited to Hejaz only. Other regions had their own share. The ancient mine of Radrad in Yemen, which yielded silver, is mentioned by Hamdani.56 It has been identified and studied. Its radiocarbon dating is c. 600 CE. Hamdani records that its inhabitants were Persians in pre-Islamic times. Gold and silver mines were also located in al ‘Irid district of Yamama and mining was the main occupation of the inhabitants of the area.57 Aqiq was a gold mine located near Falaj. It is said to be the largest mine in Arabia. It was owned by Banu ‘Aqil and about two hundred Jews were a shareholder in it.58

One important fact that comes to light by looking at carbon dating data of these mines is that commercial activity started in most of these mines in the pre-Islamic centuries. It could reflect the surge in demand for precious metals the world over during those centuries.

The mining sector was not limited to precious metals. Hamadani enumerates eleven separate iron mines in operation in Arabian Peninsula at that time.59 Wādi Abara was a copper and iron mine in Syria.60 Radiocarbon dating shows that copper mines around Sohar (Oman) were working in the fifth/sixth century CE.61 Antimony was extracted from a mountain near Al ’Alat in yamama.62 Emeralds, amethysts, quartz crystals, turquoise, borax, lead, the stone used in whetstones for sharpening swords and knives and table salt were also mined during antiquity in Arabia and exported to surrounding regions.63, 64

Service sector

The service sector is needed to initiate and maintain almost all industrial sectors except very basic industries. In the inscriptions of al-Ḥaḍr (Hatra) we read about the professions of stonemasons, sculptors, metalworkers, carpenters, scribes, tutors, priests, physicians, accountants, doorkeepers, merchants and wine sellers.65 A portion of the population earned their livelihood solely by providing services.

A unique service provided by Arabs of the nomadic zone was the protection of caravans. Hawdha bin ‘Ali, king of Yamama used to provide guards for the safety of traders of friendly countries like Sasanian Iran. This kind of service became the main source of revenue for many regions.66 Another service, as unique as the first one, which nomads could happily provide was serving in the military of foreign powers. For example, a Syrian inscription mentions ‘commander of the nomad units.’67

Some Arabs did sell their labour services. Bahila Arabs used to work in mines as labourers. Manual work was looked down upon by the Arabs generally, and so were the manual workers. Bahila were not much respected by Arabs.68 This explains why so many Persian migrant workers used to work in Arab mines. Whenever a society depends upon immigrant workers, it indicates flourishing businesses. It means mainstream people’s reluctance to do low-paid menial jobs and labour shortage.

A Market of slaves

Pre – oil Arabia

In ancient times any economic zone with a labour shortage and availability of surplus viable land ended up having an institution of slavery.69 Arabia was not an exemption. A large number of slaves used to work in farms, mines, trade, sheep grazing etc.70 There were slave markets as well, where slaves could be bought or sold. The price of a slave varied widely depending upon his usability. Slaves used to sell for ten thousand dirhams, forty thousand dirhams, five thousand Dinārs and even as many as a hundred thousand dirhams in medieval sources.71

Market fair: Pre–oil Arabia

Internal trade and commerce

Internal trade was an integral part of the economy. Pastoralists used to barter their surplus animal products (milk, clarified butter, wool, hides, skins etc.) for agricultural products (grain, oil, clothing, wine, arms etc.). Internal trade could be done any time informally or by attending grand markets at a fixed time of the year.

Describing one such market in Aflaj, Yamama, known as Sūq al-Aflaj, Lughdah al Isfahāni writes that it had four hundred shops and two hundred wells. This market, run by Bani Ja’dah, had the capacity to receive caravans and was well-defended.72 This example gives the reader a picture of what those Arabian ‘shopping malls’ looked like. In the words of Ya’qubi, “The markets of the Arabs were ten, at which they would gather for their trading activities, and other people would attend them and would be safe in respect of their lives and their possessions. Among them was Dumat al Jandal, taking place in the month of Rabi’ awal; its conveners were Ghassan and kalb: whichever of the two tribes had the upper hand would run it. Then there was Mushaqqar in (the region of Hajar in east Arabia), the market of which took place in Jumādi ‘l awwal and which was run by Tamim, the clan of Mundhir bin Sawa. Then there was Sohar (in Oman), taking place in Rajab, on its first day, and not requiring any protection. Then the Arabs would travel from Sohar to Daba, at which Julanda and his tribe would collect the tithe. Then there was the market of Shihr in Mahra, and its market took place in the shade of the mountain on which was the tomb of the prophet Hud; there was no protection at it and Mahra would run it. Then there was the market of Aden, taking place on the first day of the month of Ramaḍān, at which the Persian nobles would collect the tithe and from which the perfume would be conveyed to the rest of the provinces. Then there was the market of Sana’a taking place halfway through the month of Ramaḍān, at which the Persian nobles would collect the tithe. Then there was the market of Rabiya in Ḥaḍramaut, to get to pretentiousness was needed, for the land was not under anyone’s authority, and whoever was strongest triumphed; once there Kindah provided protection at it. Then there was the market of ‘Ukaz in the highest part of Nejd, taking place in the month of Dhu ‘l Qa’da; Quraysh would go to it and other Arabs, though most of them of [the tribal confederation of] Mudar; and there would be boasting competitions of the Arabs, [settlement of] blood-writs and truce negotiations. Then there was the market of Dhu ‘l Majaz.73

These markets were cooperative ventures. Safety of person and goods at such events was guaranteed either by the holiness of the site (e.g. Shihr under the wing of the prophet Hud), or by the prestige of a strong tribe (e.g. Kindah at Rabiya), or else by its occurrence during a holy month (e.g. ‘Ukaz in dhu ‘l Qa’da). Those in the last category were particularly popular, for their timing in a holy month also ensured ease of travel there and back and tended to promote a carnival-like atmosphere. Many tracked considerable distances to reach the markets, such as envoys dispatched by king Nu’man of Hirah every year to purchase choice wares, like leather from Yemen.74 Bedouins had to enter into a protection contract with one individual of the host tribe whom the Bedouin would pay fee and in return will get protection. This local sponsor was responsible for all activities of the Bedouin including unlawful activities.75

Almost all commodities were exchanged in these markets. Yamama sold grain to Mecca and Yathrib. Bedouins of Nejd exchanged grain from Yamama for their produce.76 Bahrain sold clothes to Yamama, and then Yamama sold them to other regions of Arabia. Arms like swords and arm plates were exchanged between different regions.77

Nomads and dwellers were interdependent

Dwellers provided the nomad with agricultural staples (grains, dates etc.), as well as manufactured items essential to their lives like weapons, cooking utensils, clothing, tent material etc. In turn, nomads provided the settlers with livestock – goats, sheeps for food, camels and horses for hauling and riding, as well as other products of animal origin like hides, wool, hair, and milk products.78

International trade and commerce

The conventional concept of trade was that people of one region exchange their surplus production with the surplus production of another region. The purpose of trade is to simply avoid the wastage of valuable goods. Ricardo buried this concept forever. He proved with the help of data that actually trading goods are purposefully produced to sell. They are not surplus. Their cost of production is low in the region from where they are exported. In turn, the same region imports certain goods from abroad whose cost of production would be higher if produced in that region. Trade adds to the overall prosperity of both trading regions.79 Before Ricardo’s writings humans might not be aware of the exact mechanism of how trade was beneficial. Still, they had realized that trade was mutually beneficial they got engaged in it from the very inception of human civilization.

No doubt, Arabian Peninsula was a conduit for international trade since antiquity. International trade continued in the pre-Islamic period, though, the profitable trade of frankincense and myrrh had long gone (see above). Historians are still scratching their heads to find out exactly what commodities did Arabia export in the pre-Islamic centuries. One commodity that Arabs sold to foreigners for sure was leather. They might have also sold finished leather goods like leather clothes; for example, aprons, pants, shoes, shoestring, boots, gloves, belts, hats etc. Furniture like cushions, covers, mats; transportation equipment like saddles, whips, harnesses, wagon parts, boat riggings, and parchments and industrial parts like bearings, bellows, machine belts and water bags all made up of leather could be part of the inventory.80 Another commodity that has been established by historians being exported was agricultural products. For example, dates were exported to Iraq, Syria, Bahrain and other places.81 But leather or dates are bulky and low-priced. They cannot make the core of a lucrative trade. There must be something else that Arabs were exporting and getting wealthy by virtue of it.

Lately, historians are pointing toward precious metals as the most valuable export commodity. This is supported by evidence from early Muslim historians. Ṭabari reports that precious metals were the major source of wealth and commerce for Meccan businessmen.82 Ibn Ishaq indicates that silver was the prime economic impetus of the Quraysh trade.83 Waqidi describes a Hejazi commercial caravan bound for Syria wherein members of Makhzūm clan of Quraysh tribe were carrying four thousand mithqāls of gold; members of Abd Manāf clan fifteen thousand mithqal of gold; and two individuals, Ḥārith bin ‘Āmir bin Nawfal and Ummayyah bin Khalf, were each carrying one thousand mithqal of gold.84

It can be postulated that Arabs carried many different kinds of commodities in their trading Caravans out of which precious metals were the most valuable and as such the most profitable.85

Nobody sells if he doesn’t need anything to buy. Arabs used some of the money they earned from exports on importing luxury goods. We know Arabs used imported items like silk from china, bamboo from India and wine from Golan.

Trade routes

Caravan en route in desert

Naturally, trade whether it was internal or international needed trade routes. Sandy and arid climatic conditions and lack of state machinery in vast areas of the Arabian Peninsula precluded road construction on lines of contemporary Byzantine Rome or Sasanian Iran. Routes, as opposed to roads, connecting different locations in Arabian Peninsula as well as outside the peninsula had started developing in the first millennium BCE. They were not only used for trade but also for pilgrimage. Caravans used to travel throughout Arabian Peninsula. The main need for caravans en route was water. Routes tended to pass through points where wells were present. It essentially meant that routes were not as straight as a crow will fly. These routes continued to be used right into the middle of the 20th century. It was only the advent of motorized traffic, railroads and metal roads that made the routes obsolete.86

Wells were easy targets of raiders. So sometimes the caravans modified the way avoiding wells and passing through khabra. (Heavy winter rain sometimes makes water pools in between dunes, called khabra). Moreover, raiding parties were faster as compared to fully laden commercial caravans. Raiders needed fewer wells as compared to commercial caravans. So routes were constantly modified according to the needs of both caravans and raiders. Actually pre-Islamic Arabia was like a checkerboard in which any point could be reached by any route.87

Khabra in desert

Enough evidence is present for the first few centuries of the first millennium and early Islamic era to map a trade route precisely. However, evidence is scanty for the centuries immediately preceding Islam. Scholars depend on early Islamic resources to trace routes of pre-Islamic Arabia.88

The last four centuries before Islam are full of incidental records of travel in Arabia over great distances, but virtually none of these records, with the exception of certain fragments of pre-Islamic poetry, contain anything remotely resembling an itinerary. We are thus forced to bear in mind the patterns of both the preceding and succeeding periods, but there is very little hope of charting any routes of the 5th and 6th centuries very precisely.89

The crossing of Arabia from southwest to northeast is mentioned in a verse of Muzahim al-Uaili. In the opposite direction, we hear of a man who keeps his family in Syria but his quarters in Yarbin. 90 Al-A‘sha (الآعشى), the Christian poet who died c. 629 CE, tells us, in a verse cited by Hamdani, that he travelled the world to earn money as a minstrel, visiting Oman, Emessa, Jerusalem; the land of the Nabataeans (settled Arabs), the land of the Persian, Najran and the land of Ḥimyarites.91 All of this simply serves to illustrate the enormity of travel in Arabia during this period, travel which cannot be reduced to a few main routes.92 Mention of diplomatic missions and military missions like the campaign of king Imru’ al Qays as far south as Najran, commemorated in Namara inscription,94 the embassy sent by Dhu Nawas to Mundhir at Ramla in 524 CE, said to be ten day’s journey to the southeast of Hirah,95 or the famous campaign of Huluban, in 552 CE, recorded in Ry 50696 all point towards the fact that enormous routes were present in Arabia in the pre-Islamic era.93

Changes in international trade

By the beginning of the 6th century CE, the Sassanians were dominant in trade and they used the Persian Gulf, followed by upper Mesopotamia to carry goods into Byzantine markets. The Byzantines were trying to dislodge the Sassanians from this trade by the use of Christians from Ethiopia and Yemen.94

Yamama and Mecca both benefited from the peace treaty of 561 CE between the Sassanians and the Byzantines. It transformed not only the routes of trade but the nature of trade. The route of trade shifted westwards and the main trading partner became Byzantine. Trade and related services improved during this truce.95 The Basran poet al-Jahiz (d. 869 CE) wrote in his tract entitled ‘a reply to the Christians’ that ‘the Arab (Quraysh) traded with Syria; they sent their merchants to the emperors of Byzantium, and conducted two yearly caravans, in winter to Yemen and in summer in direction of Syria …. They also travelled to Ethiopia … they did not, however, come in contact with Chosroes, and he in turn did not have intercourse with them.96 This last point is important, and Shahid has, in part, attributed the rise of Mecca in the 6th century to the successful diversion of caravans to it from Oman and Bahrain, formerly intended for Mesopotamia, with the concomitant and gradual abandonment of the Gulf route for the west Arabian route.97 Shahid has pointed to five factors responsible for the shift at that time. First, the intensification of hostilities between Byzantium and Sassanian Iran; second, the intensification of hostilities between the Ghassans and the lahhmids, making the caravan trade in the eastern corridor unsafe; third, the entry of the Ethiopians on the world scene, competing with Persian merchants, particularly in the silk trade; fourth, the fall of the Ḥimyarite state at the hand of Ethiopians, enabling Mecca to exert more control over the western incense route; fifth, the imposition of Byzantine and Sassanid import and export controls. Shahid suggests that three routes, Mecca-Bosra via the Wādi al Batn; Yemen-Mecca via the old incense route; and Ethiopia-Mecca across the red sea, were responsible for Mecca’s growth.98

Lately, trade became so extensive in Western Arabia that some people, like al-Safiqa, could earn without capital, probably by providing their services in bargaining or by being middlemen.99

Calendar

One important necessity of trade and travel is the wide acceptance of a dependable calendar. Arabs used a lunar calendar which, if followed exactly, loses almost ten days every twelve months. They used to make a seasonal adjustments to their calendar to avoid this problem.100 The leap months they announced kept months of each calendar month in the same season. Hubayra bin Abu Wahb, a polytheist of Mecca writes:

Many a night of Jumādā with freezing rain

Have I travelled through the wintery cold?101

This ode reflects that Jumādā was a winter month. And Jumādā awwal and Jumādā thani meant ‘the two winter months’. Rabī’ means spring and Ramaḍān means ‘the scorcher.’

Financial sector

Such extensive and diverse economic activities like agriculture, mining, manufacturing and international trade cannot sustain without the financial sector. Mecca was the financial hub of the country in pre-Islamic times. Meccans were financiers, skilful in the manipulation of credit, shrewd in their speculations, and interested in any potential lucrative investment from Aden to Gaza or Damascus. In the financial net that they had woven, not merely were all the inhabitants of Mecca caught but also many notables of the surrounding tribes.102 Interest (riba) was the backbone of the pre-Islamic financial system. The interest rate continued to increase on the lent money as time passed on.103 Part of Yathrib’s wealth was generated by Jew money lenders.104 Interest was not limited to lending money, it was charged for other valuable assets as well. Jews of Khaybar used to lend Jewellery on the occasion of marriage to the Meccans.105 Mahmood Ibrahim in his ‘Merchant capital and Islam’ demonstrates that merchant capital was behind the emergence and spread of Islam. 106

Tourism sector

A small but interesting sector of the pre-Islamic Arab economy was tourism. Amazingly, two of the busiest religious tourism centers of the modern world were functional even in pre-Islamic times. Jerusalem, though a small town by size, was the spiritual capital of the Christians. Pilgrimage to it brought prosperity to the whole region.107 Mecca, again a small town by standards of the time, owed its existence to a religious pilgrimage. It survived in the middle of the desert only because the water was available there. Many valleys converged here draining rainwater.108

Raiding sector

A negative aspect of the Arab economy, which resulted from the lack of state protection, was raiding. Whenever they got a chance Arabs supplemented their income by raiding. It was called ghazw. 109 Raiding was not a permanent hostility. It could take place between two families of the same clan or two clans of the same tribe.110 Raids were conducted mainly to acquire property like animals, goods and prisoners for ransom. Any murder committed during the raid invited vengeance.111

Raids, both among themselves and against sedentary, tended to involve small numbers of people and were of the hit-and-run type. At the very first sign of obstacle or trouble, the perpetrators would simply melt away into the desert. In the words of Procopius “The Saracens are naturally incapable of storming a wall and the weakest kind of barricade put together with perhaps nothing but mud is sufficient to check their assault …. But they are the cleverest of all men at plundering.”112 In another account, given by Nilus in the fourth century CE in Sinai, a band of Saracens attacked a group of monks, but ‘our armed guard appeared high on a hill and caused much confusion among the savages. As they made their presence known by shouting, none (of the Saracens) remained there; the whole area, which a short time ago had been full of people, became deserted.”113

Raids were not void of any perils. Bedouins were punished severely by authorities if they were caught raiding. “The Persian Arabs …. Crossed over into Byzantine territory without the Persian army and captured two villages. When the Persian governor at Nisibis learned this, he took their chiefs and executed them. The Byzantine Arabs too crossed over without orders into the Persian territory and captured a hamlet. When the general heard this … he sent Timostratus, governor of Callinicum, and he seized five of their chiefs, slaying two with the sword and impaling the other three.” 114

Natural calamities

Arabian Peninsula was not immune to natural calamities. They might have affected the economy badly. Calamities sometimes forced the nomads to infiltrate settled areas, in which case we shall consider them economic migrants. In one source “pastures of Persia ruined by drought in 536 CE and ‘about 15000 Arabs’ crossed into Byzantine lands.”115

Economy in slump

We know the economy doesn’t grow at a linear pace. It has its ups and downs. It is quite possible that Arabia was in the trough of a business cycle in the years immediately preceding the advent of Islam.116 Kennet believes that there is archaeological evidence of an economic decline in East Arabia on the eve of Islam.117 Shift of trade route from the eastern to the western part of the country could explain it. However, as we have seen earlier, there was political chaos all over. Ghassans and Lakhmids were down the drain. Yemen had entered into political uncertainties. The nomadic zone was in full political confusion. With the disappearance of already meagre state protection, the cost of conducting a business, especially trade, could have soared and the profit margin could have contracted. No wonder the Sulaym were the owners of gold mines but they could not establish their own selling business. They depended upon the Quraysh for their product to reach the markets in Damascus and elsewhere. Only Quraysh could organize ilaf contracts with individual tribes due to their high spiritual position. The Quraysh had to pay ‘protection money’ to a number of tribes on each merchandise caravan. As the Quraysh had no leverage over the price of gold in the international market, they would have not been in a position to add the high cost of the business to the final price of their product. Early Islamic sources show the big business houses of Mecca to be rich and effluent, which could be true. However, they paint the general picture of Mecca as that of the scarcity of money. The Meccans could not complete the construction of the Ka’ba due to a lack of funds just a few years before the advent of Islam (see above). We know interest rates soar high in response to the shortage of money supply in absence of a regulating central bank. Constantly increasing interest rates, as mentioned earlier, are indirect evidence of economic uncertainties which Arabia generally, and Mecca specifically, were facing immediately before the advent of Islam.

End Notes

- Louise Martin, Joy McCorriston and Rèmy Crassard, “Early Arabian pastoralism at Manayzah in wādi Ṣana., Ḥaḍarmaut,” Proceeding of the seminar for Arabian Studies 39 (2009): 271 – 282.

- Ilse Kohler-Rollefson, “Camels and Camel Pastoralism in Arabia,” The biblical archaeologist 56, no. 4 (1993): 180 – 188.

- Fred M. Donner, “The Role of Nomads in the Near East in Late Antiquity (400 – 800 C.E.),” in Traditions and innovation in Late Antiquity, eds. Clover F.M. and R. S. Humphreys, (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1989), 76.

- Michael D. Petraglia and Jeffrey I. Rose. The evolution of human populations in Arabia. New York: Springer, 2009.

- Steven A. Rosen and Benjamin A. Saidel, “The camel and the tent: an exploration of technological change among early pastoralists,” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 69, no. 1 (2010): 63 – 77.

- Fred M. Donner, “The Role of Nomads in the Near East in Late Antiquity (400 – 800 C.E.),” in Traditions and innovation in Late Antiquity, eds. Clover F.M. and R. S. Humphreys (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1989), 76.

- Muhammad bin ‘Umar al-Wāqidī. The life of Muḥammad: kitāb al-Maghāzī, ed. Rizwi Faizer, trans. Rizwi Faizer, Amal Ismail and AbdulKader Tayob, (London: Routledge, 2011), 19.

- Irfan Shahīd. Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century, (Washington: Dumbarton Oaks, 2002), Vol. 2, Part I, P 57,67.

- Irfan Shahīd. Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century, (Washington: Dumbarton Oaks, 2002), Vol. 2, Part I, P 57, 67.

- Muhammad bin ‘Umar al-Wāqidī. The life of Muḥammad: kitāb al-Maghāzī, ed. Rizwi Faizer, trans. Rizwi Faizer, Amal Ismail and AbdulKader Tayob. London: Routledge, 2011.

- Abu’l-Faraj al-Isfahani. Kitāb al-Aghani. (Cairo: 1927 – 1974). Vol 1 P 64.

- Irfan Shahīd. Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century, (Washington: Dumbarton Oaks, 2002), Vol. 2, Part I, P 1 – 20.

- Isabel Toral–Niehoff, “Late antique Iran and the Arabs: the case of al-Hira,” Journal of Persianate Studies 6 (2013): 117.

- For irrigation and its techniques in pre-Islamic Yemen see: Richard LeBaron Bowen and Frank P. Albright, Archaeological discoveries on South Arabia, (Baltimore: John Hopkins Press, 1958), 43 – 131.

- For one such agricultural community see: Jeremie Schiettecatte et. al, “The Oasis of al-Karj through time: First results of archaeological fieldwork in the province of Riyadh (Saudi Arabia)” Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies 43 (2013): 292.

- Muhammad bin ‘Umar al-Wāqidī. The life of Muḥammad: kitāb al-Maghāzī, ed. Rizwi Faizer, trans. Rizwi Faizer, Amal Ismail and AbdulKader Tayob, (London: Routledge, 2011), 103, 340, 351. According to the English translation of Waqidi’s Maghazi Khybar used to grow corn. (See Muhammad bin ‘Umar al-Wāqidī. The life of Muḥammad: kitāb al-Maghāzī, ed. Rizwi Faizer, trans. Rizwi Faizer, Amal Ismail and AbdulKader Tayob, (London: Routledge, 2011), 218). But probably it is a misnomer of the translator as corn is known to be a New World crop which was introduced to the rest of the world by early Spaniards.

- For date stones as a valuable object see: Muhammad bin ‘Umar al-Wāqidī. The life of Muḥammad: kitāb al-Maghāzī, ed. Rizwi Faizer, trans. Rizwi Faizer, Amal Ismail and AbdulKader Tayob, (London: Routledge, 2011), 341.

- Muhammad bin ‘Umar al-Wāqidī. The life of Muḥammad: kitāb al-Maghāzī, ed. Rizwi Faizer, trans. Rizwi Faizer, Amal Ismail and AbdulKader Tayob, (London: Routledge, 2011), 340.

- Muhammad bin ‘Umar al-Wāqidī. The life of Muḥammad: kitāb al-Maghāzī, ed. Rizwi Faizer, trans. Rizwi Faizer, Amal Ismail and AbdulKader Tayob, (London: Routledge, 2011), 341.

- Al-Imām abu-l ‘Abbās Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 24, 25. Here Balādhuri gives details of the use of water torrents in the fields of Yathrib.

- John C. Wilkinson, “Arab-Persian land relationship in late Sasanid Oman,” Proceedings of the sixth seminar for Arabian Studies, (London: 1973), 40-51. AND John C. Wilkinson. Water and tribal settlement in south-east Arabia; a study of the Aflaj of Oman. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977.

- Abdullah al-Askar. Al-Yamama: in the Early Islamic Era (Riyadh: King Abdul Aziz Foundation, 2002), 49.

- Montgomery W. Watt. Muhammad at Mecca (London: Oxford University Press, 1953; Repr. 1965), 2.

- For Samallaqi dam see: George C. Miles, “Early Islamic Inscriptions near Ta’if in the Hijaz,” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 7 (1948): 236 – 242.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. X, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Fred M. Donner (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1993), 108. See also: Abdullah al-Askar. Al-Yamama: in the Early Islamic Era (Riyadh: King Abdul Aziz Foundation, 2002), 49.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 89.

- Yaqut. Kitāb Mu’jam al-Buldan (Beirut: Dar Sader, 1956; repr. 1996), vol. II, P 9.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 87.

- Muhammad Ibn Ishaq. The Life of Muhammad, ed. and trans. Alfred Guillaume, (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2013), 589.

- A 6th-century house excavated at Rakka, Dammam contains a special mechanism in one room to make squash from dates. Unpublished yet.

- Sayyid Murtada al-Zubaydi. Taj al-‘Urus, (Kuwait: Matba’at al- Ḥukuma, 1965), 581.

- ‘Izz al-din ‘Ali ibn al-Athir. Al-Kamil fi al-Tarikh, ed C.J. Tornberg (Leiden: 1867) reprinted (Beirut: 1965), vol iii p 352.

- Fred M. Donner, “The Role of Nomads in the Near East in Late Antiquity (400 – 800 C.E.),” in Traditions and innovation in Late Antiquity, eds. Clover F.M. and R. S. Humphreys (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1989), 78.

- Sayyid Murtada al-Zubaydi. Taj al-‘Urus, (Kuwait: Matba’at al- Ḥukuma, 1965), vol. x, p. 9. See also: ‘Ali Jawad. Al- Mufassal fi Tarikh al-‘Arab Qabl al-Islam (Beirut: Dar al ‘Ilm lil Malayin, 1968), vol. V, P 77.

- Abu Bakr Ahmad b. Muhammad Al Hamadani ibn al Faqih. Mukhtasar Kitab al-Buldan, ed. M. J. de Goeje, (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1885), 29. See also: Abu al-Fadhil Muhammad b. Makram Ibn Manzur. Lisan al-‘Arab (Beirut: 1955), vol. XV, p. 43.

- Abdullah al-Askar. Al-Yamama: in the Early Islamic Era (Riyadh: King Abdul Aziz Foundation, 2002), 46.

- ‘Ali Jawad. Al- Mufassal fi Tarikh al-‘Arab Qabl al-Islam (Beirut: Dar al ‘Ilm lil Malayin, 1968), Vol ix p 644.

- Photo credit H. Grobe.

- Abu al-Faraj ‘Ali b. al-Husayn al-Isfahani. Kitab al-Aghani, ed M. A. Ibrahim (Cairo: Dar al Kitub, 1923 – 1959), vol. II, P 225.

- Muhammad bin ‘Umar al-Wāqidī. The life of Muḥammad: kitāb al-Maghāzī, ed. Rizwi Faizer, trans. Rizwi Faizer, Amal Ismail and AbdulKader Tayob, (London: Routledge, 2011), 11.

- ‘Imad al-Din Isma’il Abu al-Fida. Kitab al-Taqwim al-Buldan, ed. M. Reinaud et. al. (Paris: L’Imprimerie Royal Press, 1840), 99.

- Muhammad Reza-Ur- Rahim, “Agriculture in Pre-Islamic Arabia,” Islamic studies 10, no. 1 (1971): 53 – 65.

- Geoffrey R. King, “The coming of Islam and the Islamic period in the UAE,” in the United Arab Emirates: a new perspective, ed. Ibrahim al-Abed and Peter Hellyer, (London: Trident press, 1997), 70 – 97.

- Ahmad Khan, “The tanning cottage industry in pre-Islamic Arabia,” Journal of the Pakistan historical society 19 (1971): 86.

- L. Conrad, “The Arabs,” in Cambridge Ancient History, (late Antiquity: Empire and successors, AD 425 – 600), ed. A. Cameron, J. B. Ward-Perkins and M. Whitby, (Cambridge: 2000), vol. XIV, P 687 f.

- Abu ‘Ubayd ‘Abd Allah ibn ‘Abd al-‘Aziz ‘Amr al- Bakri. Mu’jam ma ista’jam, ed. Mustafa al-Saqqa, (Cairo: Marba’at Lijnat al-Ta’lif wa al-Nashr, 1945 – 1974), vol 1 p 271.

- Abu al-Faraj ‘Ali b. al-Husayn al-Isfahani. Kitab al-Aghani, ed. M. A. Ibrahim (Cairo: Dar al Kitub, 1923 – 1959), vol ii P 271 – 273.

- Yaqut. Kitāb Mu’jam al-Buldan (Beirut: Dar Sader, 1956; repr. 1996), vol ii P 9.

- Abu ‘Ubayd ‘Abd Allah ibn ‘Abd al-‘Aziz ‘Amr al- Bakri. Mu’jam ma ista’jam, ed. Mustafa al-Saqqa, (Cairo: Marba’at Lijnat al-Ta’lif wa al-Nashr, 1945 – 1974), vol. 1 p 271.

- Nur al-Din ‘Ali b. ‘Abd Allah al-Samhudi. Wafa al-Wafa bi akhbar Dar al-Mustafa, ed. Wustenfeld, (Gottingen: 1873), Vol II P 514.

- K. Ackermann, “Arabian Gold Exploration, Ancient and Modern,” Journal of the Saudi Arabian Natural History Society 3 (1990): 18-31.

- Gene W. Heck, “Gold mining in Arabia and the rise of the Islamic State,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of orient 42 (1999): 382.

- John F. Haldon. Money Power and politics in early Islamic Syria: a review of current debates (Surrey: Ashgate Publishing, 2010), 101.

- Gene W. Heck, “Gold mining in Arabia and the rise of the Islamic State,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of orient 42 (1999): 379.

- Al-Hasan b. ‘Abd Allah Lughdah al-Isfahani. Bilad al ‘Arab, ed. Hamad al Jasir et al. (Riyadh: Dar al Yamama, 1968), 177 – 178.

- Hasan ibn Ahmad al-Hamdani. Kitab al-Jawharatayn. Ed and trans. C. Toll, (Uppsala: Acta Universitaris Uppsaliensis, 1968), 145 -57.

- Al-Hasan b. Ahmad al Hamdani. Kitab sifat Jazirat al-‘Arab, ed. Ibrahim bin Ishaq al-Harbi, (Riyadh: Dar al-Yamama, 1974), 310.

- Al-Hasan b. Ahmad al Hamdani. Kitab sifat Jazirat al-‘Arab, ed. Ibrahim bin Ishaq al-Harbi, (Riyadh: Dar al-Yamama, 1974), 299.

- Al-Hasan b. Ahmad al Hamdani. Kitab sifat Jazirat al-‘Arab, ed. Ibrahim bin Ishaq al-Harbi, (Riyadh: Dar al-Yamama, 1974), 299.

- Irfan Shahīd. Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century, (Washington: Dumbarton Oaks, 2002), Vol. 2, Part I, P 136.

- Tony J. Wilkinson and Paolo costa, “The hinterland of Sohar: Archaeological surveys and excavations within the region of an Omani seafaring city,” The Journal of Oman Studies 9 (1987): 1 – 238.

- Yaqut. Kitāb Mu’jam al-Buldan (Beirut: Dar Sader, 1956; repr. 1996), Vol. III p. 709.

- Nur al-Din ‘Ali b. ‘Abd Allah al-Samhudi. Wafa al-Wafa bi akhbar Dar al-Mustafa (Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al- ‘Ilmīyah, 1955), Vol. iv P 1218. AND Al-Hasan b. Ahmad al-Hamadani. Sifat Jazirat al-‘Arab, ed. M. al-Akwa’, (Riyadh: Dar al-Yamamah,1977), 293, 300 -301.

- Ruins of Tabala have been discovered about 35 km north of Bisha, Saudi Arabia. Its name is linked to a pre-Islamic temple (also called the Yemeni Ka’ba). Umayyad commander Hajjaj bin Yusuf served as a governor of this town under Caliph ‘Abd al Malik bin Marwan (685 – 705). Hamdani tells that it was a village of shopkeepers inhabited by members of the Quraysh tribe and that people of the desert destroyed it. researchers have established that it was a mineral extraction center; mines are discovered nearby at Sada’, Manazil, Wakba and ‘Abla. (Muhammad bin ‘Abdulrahman Rashid Al-Thanayan, in The Yemeni Pilgrimage Road in Roads of Arabia ed. ‘Ali ibn Ibrāhīm Ghabbān, Beatrice Andre-Salvini Francoise Demange, Carine Juvin and Marianne Cotty (Paris: Louvre, 2010), 484.)

- Edward Lipinski. Studies in Aramaic inscriptions and Onomastics. Leuven: Peeters publishers, 2010.

- Abdullah al-Askar. Al-Yamama: in the Early Islamic Era (Riyadh: King Abdul Aziz Foundation, 2002), 52.

- Littmann, Eno. Semitic inscriptions. Leiden: (publications of the Princeton University Archaeological Expeditions to Syria 1904 – 5 and 1909, division 4), 1914 -49 (Parts A – D).

- Abdullah al-Askar. Al-Yamama: in the Early Islamic Era (Riyadh: King Abdul Aziz Foundation, 2002), 50.

- Hellie, Richard. Slavery. Encyclopedia Britannica, 2009.

- Abdullah al-Askar. Al-Yamama: in the Early Islamic Era (Riyadh: King Abdul Aziz Foundation, 2002), 46.

- Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahani. Kitab al-Aghani (Cairo: 1927 – 1974), Vol 6 P 26.

- Al-Hasan b. ‘Abd Allah Lughdah al-Isfahani. Bilad al ‘Arab, ed. Hamad al Jasir et al. (Riyadh: Dar al Yamama, 1968), 222, 273.

- Ahmad ibn Abi ya’qub al-Yaqubi. Ta’rikh. ed. M. T. Houtsma (Leiden: Brill, 1883), vol I P 313 – 14.

- Robert G. Hoyland. Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam (New York: Routledge, 2001), 110.

- ‘Imad al din Isma’il abu al Fida. Kitab Taqwim al-Buldan, ed. M. Reinaud et al. (Paris: L’Imprimerie Poyal Press, 1840), vol III p 352.

- Abu Ubeyd Al Bakri. Kitab al-Mamalik wa al-Masalik,. ed. Al-Ghunaym (Kuwait: 1977), 119.

- Yaqut al-Hamawi. Mu’jam al-Buldan. ed. A. W. T. Juynboll, (Laydin: Brill,1861), vol. III p. 391.

- Fred M. Donner, “The Role of Nomads in the Near East in Late Antiquity (400 – 800 C.E.),” in Traditions and innovation in Late Antiquity, eds. Clover F.M. and R. S. Humphreys, (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1989), 77.

- David Ricardo, On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, (London: John Murray, 1817): 146 – 185.

- Abdullah al-Askar. Al-Yamama: in the Early Islamic Era (Riyadh: King Abdul Aziz Foundation, 2002), 43 – 55.

- Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahani. Kitab al-Aghani, (Cairo: 1927 – 1974), vol. II p 107.

- 82. Tabri 1881 vol 1 Pp 1374 – 1375.

- Muhammad Ibn Ishaq. The Life of Muhammad, ed. and Trans. Alfred Guillaume, (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2013), 364.

- Muhammad bin ‘Umar al-Wāqidī. The life of Muḥammad: kitāb al-Maghāzī, ed. Rizwi Faizer, trans. Rizwi Faizer, Amal Ismail and AbdulKader Tayob, (London: Routledge, 2011), 15

- Gene W. Heck, “Arabia without spices: an alternate hypothesis,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 123, no. 3 (2003): 547 -576.

- Danial T. Potts, “Trans-Arabian routes of the pre-Islamic period,” In L’Arabie: ses mers bordieres, I. Itineraires et voisinage, ed.Jean-Francois Salles, (Lyon: Maiso de I’Orient, 1988), 126-62.

- Danial T. Potts, “Trans-Arabian routes of the pre-Islamic period,” In L’Arabie: ses mers bordieres, I. Itineraires et voisinage, ed. Jean-Francois Salles, (Lyon: Maiso de I’Orient, 1988),128.

- Danial T. Potts, “Trans-Arabian routes of the pre-Islamic period,” In L’Arabie: ses mers bordieres, I. Itineraires et voisinage, ed. Jean-Francois Salles, (Lyon: Maiso de I’Orient, 1988), 126-62.

- Danial T. Potts, “Trans-Arabian routes of the pre-Islamic period,” In L’Arabie: ses mers bordieres, I. Itineraires et voisinage, ed. Jean-Francois Salles, (Lyon: Maiso de I’Orient, 1988), 135.

- Ulrich Thilo. Die Ortsnamen in der altarabischen poesie. (Wiesbaden: Harrassowits, 1958), 101, 114.

- Aloys Spernger, “Vershuch einer Krittik von Hamdanis Beschreibung der arabischen Halbinsel und einige Bemrkunge uberr Professor Davd Heinrich Muller’s Ausgabe derselben,” Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenlandischen Gesellschaft 45 (1891): 392-393.

- Danial T. Potts, “Trans-Arabian routes of the pre-Islamic period,” In L’Arabie: ses mers bordieres, I. Itineraires et voisinage, ed. Jean-Francois Salles, (Lyon: Maiso de I’Orient, 1988), 136.

- For the campaign of Imru’ al Qays see: James A. Bellamy, “A new reading of Namarah inscription,” Journal of American Oriental Society 105 (1985): 47-48. For the embassy of Dhu Nawas see: Irfan K. Shahīd, “Byzantino-Arabica: the conference of Ramla, A.D. 524,” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 23 (1964): 115-131. For the campaign of Huluban see: Alfred F. L. Beeston, “Notes on the Muraighan inscription,” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies (1954): 389 – 92 (RY 506).

- Francis E. Peters. The Arabs and Arabia on the Eve of Islam: The Formation of the Classical Islamic World. (Surrey: Ashgate, 2010), XVII.

- Ibn al-Athir, Al-kamil fi al-Tarikh, vol. III p 352. See also: Abdullah al-Askar. Al-Yamama: in the Early Islamic Era (Riyadh: King Abdul Aziz Foundation, 2002), 54.

- Joshua Finkel, “A Risala of Al-Jahiz,” Journal of American Oriental Society 47 (1927): 325.

- Irfan K. Shahīd, “The Arabs in the peace treaty of A.D. 561,” Arabica 3 (1957): 184, 191-192.

- Irfan K. Shahīd, “The Arabs in the peace treaty of A.D. 561,” Arabica 3 (1957): 181 – 213.

- Irfan K. Shahīd, “The Arabs in the peace treaty of A.D. 561,” Arabica 3 (1957): 181 – 213.

- Patricia Crone. Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987), 173 -77. See also: Ibn Ishaq, the life of Muhammad, 22.

- Muhammad Ibn Ishaq. The Life of Muhammad, ed. and Trans. Alfred Guillaume, (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2013), 405.

- Montgomery W. Watt. Muhammad at Mecca (London: Oxford University Press, 1953; Repr. 1965), 4.

- Tabri, Tafsir, Vol IV, P 55 in connection with Sura 3: A’yat 130.

- Muhammad bin ‘Umar al-Wāqidī. The life of Muḥammad: kitāb al-Maghāzī, ed. Rizwi Faizer, trans. Rizwi Faizer, Amal Ismail and AbdulKader Tayob. London: Routledge, 2011. See also: David S. Margoliouth. Muhammad and the rise of Islam (New York: knickerbocker press, 1905), 189.

- Muhammad bin ‘Umar al-Wāqidī. The life of Muḥammad: kitāb al-Maghāzī, ed. Rizwi Faizer, trans. Rizwi Faizer, Amal Ismail and AbdulKader Tayob, (London: Routledge, 2011), 330.

- Mahmood Ibrahim, Merchant Capital and Islam, Austin: University of Texas Press, 1990.

- Irfan Shahīd. Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century, (Washington: Dumbarton Oaks, 2002), Vol. 2, Part I, P 77.

- Jacqueline Chabbi, “origins of Islam,” in Roads of Arabia, ed. ‘Ali ibn Ibrāhīm Ghabbān, Beatrice Andre-Salvini Francoise Demange, Carine Juvin and Marianne Cotty, (Paris: Louvre, 2010), 10.

- For the use of the word ghazw in pre-Islamic Arabic see: Gustave E. Grunebaum, “The nature of Arab Unity before Islam,” Arabica 10, no. 1 (1963): 17. The word did not have any religious meaning during the first few centuries of Islam. Actually, Tabari, writing in 915 CE, uses the word ‘ghazw al baḥr’ to describe ‘naval war’. See: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. R. Stephen Humphreys (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 26.

- Louise Sweet, “Camel raiding among the Bedouins of north Arabia: a mechanism of ecological adaptation,” American anthropologist 67 (1965): 1132 – 50.

- Matthew S. Gordon. The Rise of Islam (Westport: Greenwood, 2005), 5.

- Procopius. History of the wars and Buildings, ed. and trams. H. B. Dewing, (London: William Heinemann, 1914), vol. II P 19.

- Monachus Nilus, “Narrations,” in Bibliotheca Patrum Graeca, ed. Jacques-Paul Migne, (1865), vol. 79, P 669.

- Joshua, the Stylite. Chronicle, ed. and trams. W. Wright, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1882), 88.

- Comes Marcellinus, “Chronicle,” in Bibliotheca Patrum Latina, Ed. ed. Jacques-Paul Migne, (1846) vol. 51, P 943.

- Christian Julien Robin, “Arabia and Ethiopia,” in The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity, ed. Scott Fitzgerald Johnson, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 309.

- Derek Kennet, “On the Eve of Islam: Archaeological Evidence from Eastern Arabia,” Antiquity 79 (2005): 107 – 118. AND Derek Kennet, “The Decline of Eastern Arabia in the Sasanian Period,” Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy 18 (2007): 86 – 122.