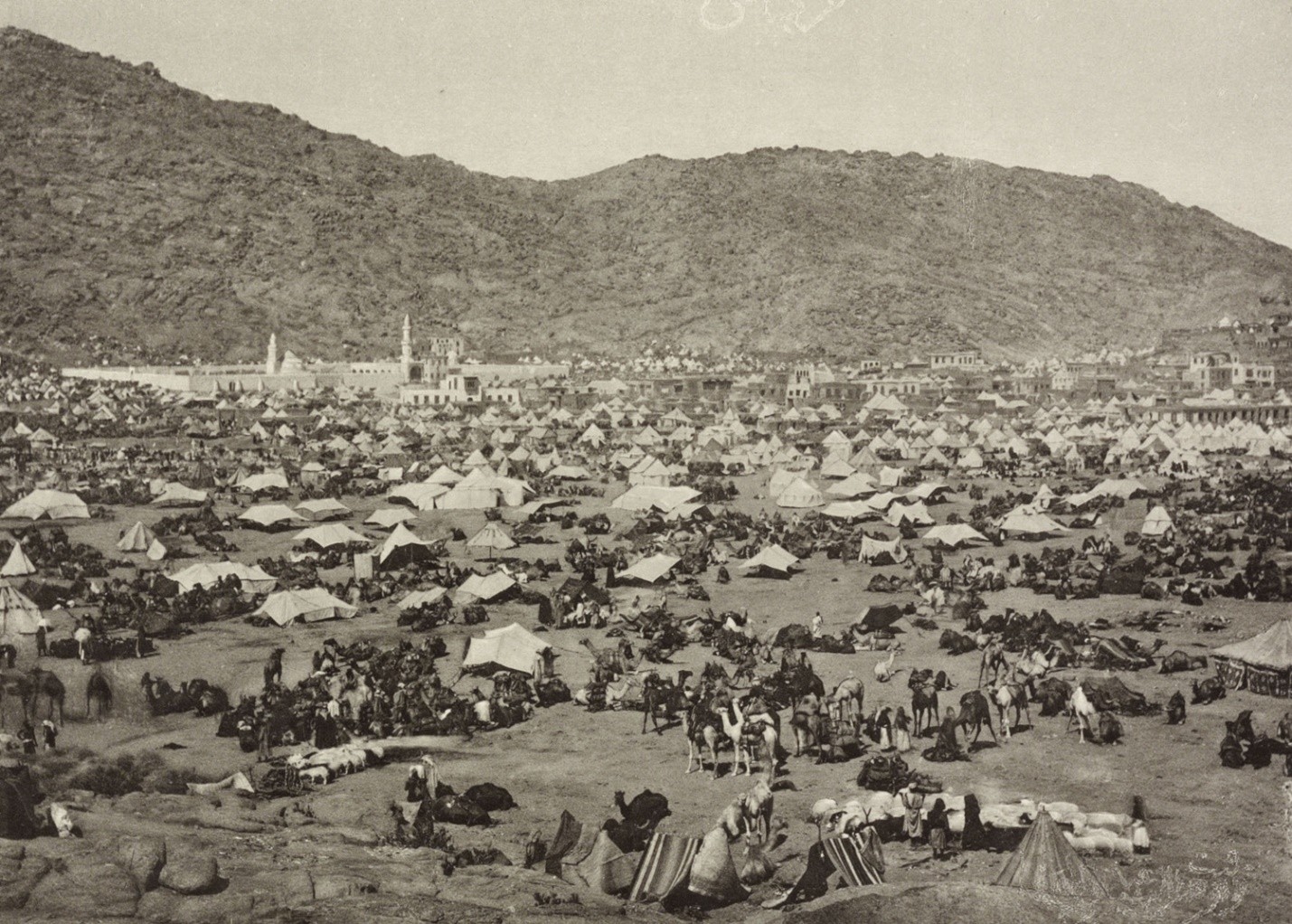

Yathrib was a large oasis in pre-Islamic Arabia. It was a congregation of neighbourhoods rather than one town. 1 The population of Yathrib was both Arab and Jew. Initially, after the Immigration of Prophet Muhammad, the name Yathrib was changed to “the city of the Prophet” and later it became known as ‘the city’ – Medina.2 When exactly this change took place, we do not know. By the way, Abu Qays bin Abu Anas, a resident of Yathrib before Islam, calls this oasis by name of Tayba (Ṭaybah طَيبَه) in his ode.3 It is the honorific of Yathrib, meaning ‘the Fragrant’.4. The larger size of Yathrib as compared to Mecca is evident from the claim of Ma’mar that there was a city wall around Yathrib while it is known that Mecca had none. 5

It has been mentioned earlier that the Jews of Yathrib had the upper hand over Arab tribes in the second half of the sixth century CE. At the beginning of their settlement, Aws (اَوس) and Khazraj (خَزرَج), two Arab tribes who had migrated from Yemen, were subordinate to the Jews. The Jews had allowed them to develop and use relatively infertile lands as Tabari describes them as ‘mawālī ‘l yahūd’.6 In the words of Nu’aym bin Mas’ud, of the Ghatafan tribe, who acted for the Muslims during the battle of Khandaq, “Banu Qurayẓah were people of nobility and of properties while we were Arab people possessing neither dates nor grapevine. Rather we were a people of sheep and camels.7 A proof of the subordinate position of the Arabs was the ius primae noctis exercised by Fityawn of Banu Tha’labah, a Jew clan. Malik bin Ajlan (Malik bin ‘Ajlān مَلِك بِن عَجلان) of Khazraj challenged it when Fityawn wanted Malik’s sister to spend her first night as bride with him. Malik was able to make himself independent.8 As time passed, Arabs grew in power and no longer remained subordinate to the Jews. It is evident from the fact that the Jews had to become confederates of the Arabs. Banu Unayf, a Jew clan, was confederate of Banu Jahjaba’ (Jaḥjabā’ جَحجَبَاء) clan of Aws.9 Qaynuqa (Qaynuqā’ قينُقاع) were confederates of Abdullah bin Ubayy (‘Abdallāh bin Ubayy عَبد اللَّه بِن اُبَى) of khazraj and had provided him with seven hundred men in the battles that took place before Immigration (hijrah هِجرَة).10 An indirect proof that Arabs had grown stronger comes from the fact that they could afford the luxury of fighting among themselves which we shall discuss just now.11

Pre-Islamic civil war at Yathrib

As the population of Yathrib grew, pressure on limited agricultural sources increased. In this scenario clashes between different groups were inevitable. Small battles evolved into full-fledged war followed by a law and order situation that was free for all. These events, which engulfed the whole population of Yathrib, are referred to as the Civil War at Yathrib.12 Aws and Khazraj are described as two warring Arab tribes of Yathrib. 13 Genuinely it was not a war between two tribes per say. Rather it was among them. All their clans were fighting with each other to expel the defeated from their land. It means a fight could erupt between two clans of the same tribe if they were neighbours.

Street of Medina: C. 1923 CE. 14

This situation needed a neutral person of authority who could settle the dispute. Abdullah bin Ubayy, a leader of the Awf (‘Awf عَوف) clan of Khazraj seems to have attempted to play neutral at Bu’ath – at least he did not take part in the fighting.20 Neither did he execute those Jew hostages after the war of Bu’ath that were deposited with him.21 He had participated in many battles preceding Bu’ath. So, the only reason for not participating in the war of Bu’ath could be that he had realized that it was a ‘war by all against all’ and nobody could win it and that Yathrib needed a neutral person to bring peace by treating all parties fairly. He wished to be that neutral person. It is said his supporters were preparing to crown him as king of Medina when Prophet Muhammad appeared on the scene.22 One reason Abdullah bin Ubayy did not succeed in becoming king of Medina could be that being a member of one of the warring parties, Khazraj, he would not have been perceived as neutral by all the factions. Salima (Salīmah سَلِيمَه), Zurayq (زُرَيق) and Najjar (Najjār نَجّار) clans of Khazraj, who produced first Muslims in Yathrib were big in number but had failed to produce any leader of prominence. They participated in Bu’ath but sources do not mention any noteworthy leader from these clans.23 They might have perceived Abdullah bin Ubayy as part of the problem rather than a solution. They were looking for an outsider and Prophet Muhammad perfectly matched with their requirement.24 A prophet, with authority resting on religion rather than descent, was the best arbitrate between them at this point in time. The Arabs of Medina imagined Prophet Muhammad to be the Messiah expected by the Jews and hastened to get on good terms with him.25 It is not surprising that A’isha, the wife of Prophet Muhammad, is reported by Samhudi saying “The day of Bu’ath had been arranged by Allah for the benefit of Muslims.”26

Arrival of the Prophet in Medina

The prophet was received with honour and joy by the Arabs of Yathrib. Anas bin Malik (Anas bin Mālik اَنَس بِن مالِك) of Khazraj, an early Muslim from Medina, asserts that five hundred Ansars came out to welcome him.27 An Ethiopian war dance was organized to make the occasion auspicious.28 Ansar (Anṣār اَنصار) is the name by which early Arab Muslims of Medina are called by the early Islamic sources. Ansar means ‘helpers’ as they were considered helpers of the Prophet for the sake of Allah.29

Ancient roof of wood and straw from ruins of Khaybar:

Roof of Mosque of Prophet might be similar.30

Prophet Muhammad’s stay with Khalid bin Zayd (Khālid bin Zayd خالِد بِن زَيد) of Najjar clan, better known as Abu Ayub Ansari (Abū Ayūb al-Anṣāri اَبُو اَيُّوب اَلاَنصارِى), was transient for about ten months. 32 Najjar clan of khazraj was by far the most numerous among all Arab clans of Medina and constituted thfe biggest part of Ansar. Their lands were located centrally.33 The Prophet bought land in this central part and quickly got busy in building a mosque with the help of the Muslims and shifted into it when it was ready.34 Later on, this mosque acted not only as haram (ḥaram حَرَم sanctuary) of Islam but also as a town hall and audience chamber of the town.35

Chronology of events at Medina

Waqidi, in his Kitab al Maghazi (Kitāb al Maghāzi كِتاب المَغازى), has listed seventy four expeditions with dates.36 Scholars relate events at Medina with those dates to establish chronology.37 Kitab al Maghazi has made establishing chronology of events at Medina comparatively easier than those at Mecca.

Establishment phase

Immigration of Quraysh Muslims from Mecca to Medina was a big milestone in the struggle of Islamic movement. The new residents of Medina were named Muhajirun (Muhājirūn مُهاجِرُون). The word Muhajirun meant ‘those who immigrated for the sake of Allah’. Combination of Muhajirun and Ansar of Medina increased number of Muslims at one location to almost double. Immediately after reaching Medina, Islam no longer remained a purely spiritual movement. It rather became a blend of spiritual cum political movement. Prophet Muhammad, who had been their spiritual leader, became their political leader as well.

Immigration opened up new kind of challenges to the Muslims at the same time.

The first issue the Muhajirun faced immediately after Immigration was the scarcity of jobs. Muhajirun were underemployed in Medina. Some of them had to hew wood and draw water.38 Prophet Muhammad himself suffered. ‘Months used to pass without any fire being lighted in our dwelling, our food being dates and water’, says A’isha.39 Ansar helped Muhajirun by sharing their resources during this phase of underemployment. However, some late-coming Muhajirun, such as Miqdad bin Amr (Miqdād bin ‘Amr مِقداد بِن عَمرو, is better known as Miqdad ibn al-Aswad al-Kindi) did not find any Ansar to help them. 40

The practice of ‘brothering’ one Muslim with another had started even before Immigration. For example, Abdur Rahman bin Awf was the brother of Sa’d bin Waqqas as well of Sa’d bin Rabi’ (Sa’d bin Rabī’ سَعَد بِن رَبِيع).41 It was not compulsory to pair a Muhajirun with an Ansar. Prophet Muhammad was the brother of Ali and Hamza was the brother of Zayd bin Haritha. Some Muslims even had not got any brothering partner. The exact reason for brothering is not clear. Early sources mention that the pair of brothers used to share their resources. It could also have served the purpose of knitting Muhajirun and Ansar together. In any case, ‘brothering’ was abandoned later. It is not clear if it was near the battle of Badr or afterwards. It could be due to difficulties in inheritance.42

Challenges on political and spiritual fronts were not less formidable.

It was the Arab population of Medina who had invited the Prophet. Some of them accepted Prophet Muhammad as their political as well as religious leader wholeheartedly. Others accepted him only as a political leader.43 This later group of Arabs of Medina is called Munafiqun (Munāfiqūn مُنافِقُون) by the earliest Islamic sources. The literary meaning of Munafiqun is “hypocrite” and does not warrant further explanation, as readers of all cultures and countries understand it well. The Munafiqun proclaimed belief in prophethood of Prophet Muhammad verbally but their actions were contrary to it. They continued to challenge the authority of the Prophet throughout his life. Abdullah bin Ubayy, who had accepted Islam lately, became their leader according to early Islamic sources.44

Jews of Medina, though no longer governors over Aws and Khazraj by the time of Immigration, were still powerful. Samhudi mentions fifty-nine Jewish strongholds (Āṭām) in Medina as compared to only thirteen of the Arabs.45 Main Jewish tribes in Medina were three, Qurayzah, Nadir and Qaynuqa. Out of the three, Qaynuqa did not possess any agricultural land. They conducted a market and practiced crafts such as goldsmiths.46 Nadir and Qurayzah were owners of the richest fertile lands, mainly in the south of the town.47 Samhudi gives names of some other clans who were Jewish.48 One of them was Tha’labah who is particularly said to be of Arab origin.49 One Jew clan noted by Ibn Ishaq is Zurayq.50

From the very beginning, Jew’s reaction to the Immigration of Meccan Muslims to Medina was different from that of Arabs of Medina. There is no mention in sources if any of the Jews from Medina contacted or negotiated with Prophet Muhammad at Mecca before Immigration. 51 They were nervous about the presence of another monotheist religion in their town. Safiya bint Huuyayy (Ṣafiya bint Ḥuuyayy صَفِيَه بِنت حُيِى), a Jewess of Nadir who later became Prophet’s wife, testifies that her father and uncle were gloomy the day Prophet reached Quba. 52

The presence of Jews in Medina produced a new kind of ideological hostility which was different from the one that Muslims had in Mecca. The Jews could argue that Prophet Muhammad was wrong and even ignorant because they could point to their own written religious tradition and their written history, which contradicted Prophet Muhammad’s message and was a known and respected tradition in northern Arabia and Syria. Meccans had an intellectual religious tradition that was not written down and was not known in Syria or other advanced areas. Thus Jews had more international prestige than the Meccans and so could harm Prophet Muhammad in a different way. 53

In the beginning, Muslims and the Prophet adopted a friendly policy towards the Jews.54 This hypothesis is supported by a tradition recorded in Isabah that the Prophet declared the Jewish day of Atonement, the day he reached Quba, as the day of fasting.55 The same spirit reflects from the incident when a Jew’s funeral passed and the Prophet and his Companions (Ṣiḥābah صِحابَه) stood up till it was out of sight.56, 57 Similar impression arises from the tradition recorded by Tabari that Prophet Muhammad started to pray facing towards Jerusalem right after the Immigration to please the Jews of Medina. 58, 59 The Muslims recognized the Jews as a separate political entity. Waqidi tells us that when Prophet Muhammad came to Medina all the Jews made an agreement with him, of which one condition was ‘that they were not to support any enemy against him’.60

Other important role players in the political situation of Medina were the polytheist Arab tribes living in surrounding areas of Medina. The Prophet looked for being on friendly terms with these tribes. It was a precondition for any expedition outside Medina so Muslims could not be molested while operating in their territories. The first such treaty of friendship was made with Mudlij and Damrah (Ḍamrahضَمرَه) clans of Kinanah (Kinānah كِنانَه) in 623 CE during an expedition.61 As the main body of Kinanah remained friendly to the Meccan Quraysh up until Fath Mecca by the Muslims, Watt guesses that these clans might not be on good terms with the Meccans.62 The text of the treaty, preserved by Ibn Sa’d, prescribes mutual help (naṣrنَصر).63 In Watt’s opinion it was a pact of mutual non-aggression.64

Prophet Muhammad also looked for supporters from surrounding Arab tribes to join his Expeditions. Juhaynah were confederates with the Khazraj and Muzainah with Aws during the battle of Bu’ath and the close relations continued.65 In this way Prophet Muhammad had indirect alliance with them from the very onset in Medina. People of Juhaynah helped the Muslims in their spying efforts at the time of battle of Badr.66 Muzainah spied on the Quraysh when they were returning from Uhud.67 We continue to hear occasional men from Juhaynah and Muzainah joining Muslim Expeditions. Some of them died at Uhud fighting from Muslim side.68 However, none of them joined Prophet Muhammad en mass in early phases of Islam in Medina. Generally, Juhaynah and Muzayah were poor and weak. They did not have the capacity to attack Medina as Ghatafan (Ghaṭafān غَطَفان) did in the battle of Khadaq.69 Their ‘deputation’ during the ‘year of deputations’ consisted of two men who only spoke for themselves.70The Muslims had to carry out very few expeditions against the tribes in the environs of Medina, even when they grew strong. We hear of expedition of 627 CE, against Mustaliq (Muṣṭaliq مُصطَلِق) clan of Khuza’ah (Khuzā’ah خُزاعَه).71 Another small expedition was in 629 CE against a tiny section of Juhaynah in 629.72

Constitution of Medina

From day one the Prophet started working in the direction of establishing law and order in Medina. At some date during the early months in Medina, Prophet Muhammad cancelled all blood feuds among the Muslims that arose from the Jahiliyyah (Jāhilyyah جاهِلِيَه), the era before the advent of Islam. He made it illegal for Muslims to kill any fellow Muslim in revenge for the murder of a polytheist.73 A few months later, he started making the murderer personally responsible for the crime, rather than his whole clan. He practically applied these principles when one Muslim from Aws murdered another from khazraj in revenge for a pre-Islamic murder. The culprit was arrested, convicted in light of the evidence, and sentenced to death.74 Rudimentary state was attaining a monopoly on violence, which is a basic function of the state. 75 Blood money matters between the Jews and Aws or Khazraj were kept untouched.76

Ibn Ishaq has preserved a document, which he calls ‘covenants between the Muslims and the Medinites and with the Jews’.77 It is all about the initial endeavours of Prophet Muhammad to maintain law and order in Medina. Historians conveniently name it the ‘Constitution of Medina’. Ibn Ishaq does not give any date for the document but mentions that it was an agreement. Ibn Ishaq used the word ṣaḥīfah (translated as a document by most scholars) to describe this document, meaning it was written formally and accepted by all parties to the pact.78 The document appears to be genuine to Wellhausen, and not a later falsification.79

Most modern scholars agree that this document would have developed over a period of time. Its earliest clauses could have started developing by the time of the Pledge of Aqaba and the last clauses could have developed just after the battle of Uhud.80 Serjeant analyses that the document amalgamates originally different agreements, probably eight in number, though one or two of them might not be an agreement in itself but rather an appendix to other agreements, which have been noted collectively by Ibn Ishaq. Each of them belongs to a different date, though their chronological order is uncertain. Generally, it can be assumed that documents in which the name Yathrib appears are of an earlier age than those documents in which the title al-Medina appears. Similarly, documents where we find simply ‘Muhammad’ are of an earlier age than those where we find Muhammad with the epithet ‘Messenger of Allah’. They demonstrate different levels of Prophet Muhammed’s power over time.81

The ‘Constitution of Medina’ is a lengthy document, written in purely legal language, enumerating a multitude of rules, some of them ambiguous. It is apparent that some rules were specific to certain parties but it is not clear from the wording, who were binding parties to that particular rule. The document begins with a series of identical clauses which run, ‘the immigrants of Quraysh (or the Banu Sa’idah or Banu Jusham or other Medinan tribes), according to their former custom, will give and take blood money between themselves, and they will ransom their prisoner according to the common custom (ma’rūf) and share (qist) among the believers (Mu’minūn). A second provision makes the group responsible for paying blood money on behalf of a person who becomes a Muslim but is not attached to any group of Muslims. Yet another clause makes the Mu’minūm and Muttaqūn responsible for taking action against one of their member who commits a crime that causes dissension among the Mu’minūm, even if he be one of them. No Mu’min is to be executed in revenge for a Kāfir (polytheist). Other clauses guarantee mutual security and lay down arrangements for a common defence against an external foe. A second document in the series extends what is in the first, dealing with the question of murder and blood money among the Mu’minūn, outlawing the murderer (muhdith). It also outlaws the man who protects the murderer, stating that from him will be received neither sharf nor adl. These passages come from a document that should be dated before the invasion of Medina by the Quraysh and when the Jew confederates of Aws were associated with Arab tribal groups in the defence of the town. In a later document, later because Prophet Muhammad is called Rasūl Allah, it is declared that the center of Yathrib is ḥaram for people of this sheet and any dispute between them will be referred to Allah and Muhammad.82, 83

Interestingly, the document binds only the disagreeing clans to the judgement of Prophet Muhammed. No obedience to the Prophet is demanded in case they agree with each other. It means Medina became a confederation of self-governing tribes presided over by Prophet Muhammed, whose judgement was absolute in case of their disputes.84

As the document declares Medina a haram (ḥaram حَرَم) it would have prevented murders inside Medina.85 Development of the ‘Constitution of Medina’ thrust the final nail in the coffin of the Civil War at Medina.

The concept of Ummah

Ibn Ishaq mentions in the introduction to the ‘Constitution of Medina’ that it was a covenant concerning Muhajirun, Ansar and the Jews. Then the document opens with: ‘In the name of Allah the Compassionate, the Merciful. This is a document from Muhammad the Prophet between the believers (Mu’minūn) and Muslims (Muslimūn) of Quraysh and Yathrib and those who followed them and joined them and laboured with them. They are one community (ummah)’86. To Watt, Sergeant and many others it is obvious that ‘those who followed them and joined them and laboured with them’ are Jews. Both scholars believe that Jews are included in the ummah mentioned in the document, in addition to the believers and Muslims of Quraysh and Yathrib.87 In this sense, there is no religion, according to Serjeant, in the arrangement that the Constitution of Medina had generated. That is the reason armed Jewish tribes could fit into this arrangement. Sergeant emphasizes this point further by noting that the Constitution of Medina does not speak of the parties as the Ansar and Muhajirun, so it is an agreement between tribal groups – Quraysh and those of Yathrib.88

Others beg to differ. Donner believes that the Constitution of Medina is a political document written on religious background. Certain terms used in the Constitution of Medina, like Mu’minun, are purely religious in tone.89 Donner further notes that the concept of Ummah – that the tribes are united due to the same religion – was present among Muslims at the time of the development of the Constitution of Medina and can be observed at the battle of Badr, which is contemporary to the Constitution of Medina. Hence, the Constitution of Medina has used the term ummah in a religious spirit. Donner further believes that it was this concept of the ummah – unity around religion – which helped Islam expand to the whole pagan population of Arabia.90, 91, 92

Break up with Jews

The Prophet Muhammad offered Islam to the Jews of Medina after Immigration. Very few of them converted to Islam. One of them was Abdullah bin Sallam (‘Abdallah bin Sallām عَبد اللَّه بِن سَلَّام) from Qaynuqa. His pre-conversion name was Husayn bin Sallam (Ḥuṣayn bin Sallām حُصَين بِن سَلَّام). As a consequence, he was maligned by the other Jews.93 A group of another eight Jews from Qaynuqa converted as well, but they were Abdullah bin Ubayy’s party and ended up being Munafiqun.94 Some others converted later. Mukhayriq from Tha’labah converted on the occasion of the battle of Uhud. He was killed in the same war, fighting from the Muslim side.95 Few converted at the time of the attack on Nadir and Qurayzah. 96 Generally speaking, Jews as a group maintained their own religion after the Immigration.

Though Jews were rich, the main disagreement between the Jews and the Prophet was not that of wealth or power but was theological. They were the most vocal opponents of the prophethood of Muhammad in Medina. 97 After a few months of presence in Medina, the Prophet realized that conversion to Islam would never be fashionable among the Jews of Medina. And they will remain a security threat to the Muslims.

On February 11, 624 CE, about seventeen months after Immigration, Prophet Muhammad ordered the Muslims to abandon qibla of Jerusalem and change to Ka’ba. 98 Watt considers it an announcement of a formal breakup with the Jews. 99 The prophet undertook a series of measures after the change of qibla up to the war on Khayber to get rid of Jews rather than to persuade them towards Islam. 100 The only occasion after the formal break up where the Prophet invited Jews towards Islam was immediately after returning from the battle of Badr in the market of Qaynuqa.101

First Raids

Soon after the Immigration, the Muslims got engaged in raiding. The idea of utilizing the position of Medina for attacking the caravans of the Quraysh was first announced by a Muslim who had visited the Ka’ba shortly after the Immigration. 102 Though, according to the earliest Muslim sources, the only reason for raids was to fight against infidels (jihād جِهاد), as it was prescribed by Allah by that time, Margoliouth believes underemployment among Muhajirun would have been a stimulus for raids. 103

According to Ibn Ishaq, the first raid was carried out twelve lunar months after the Immigration. 104 It consisted of two parties; one was sent against the Quraysh and Kinanah under the leadership of Ubayda bin Harith (‘Ubayda bin Ḥārith عُبَيدَه بِن حارِث) and the other was sent under leadership of Hamza bin Abdul Muttalib against the Quraysh in the territory of Juhaynah.105

Waqidi notes a total of eight expeditions during the first eighteen months of Immigration. They were all, except one, against the Meccan caravans which had to pass between Medina and the Red Sea.106 Even if they passed furthest away from Medina, it was possible to ambush them and return to Medina safely before any rescue party arrives from Mecca. 107 Prophet Muhammad participated in some of these eight expeditions himself.108 All expeditions except one, against Meccan caravans indicates Prophet Muhammad’s attitude towards the Meccans.109 Quraysh of Mecca, on their part, upheld their efforts to get Prophet Muhammad killed. They asked Abdullah bin Ubayy and other pagan Aws and Khazraj to either kill or expel Prophet Muhammad, threatening war with the help of other Arab tribes if they fail to do so. The Prophet got wind of it and confronted them to explain their position.110

The number of people in the first seven expeditions ranges from twenty to two hundred. 111 There were less than a hundred Muhajirun in Medina. Even if we consider some who joined later during the first year of Immigration, their number cannot exceed one hundred and fifty. It means some Ansar participated in these expeditions as well.112 Caravans attacked by them were large. One of them consisted of twenty-five hundred camels. People accompanying them were two hundred to three hundred.113

The only expedition during the first eighteen months of Immigration that was not against the Meccans was against Kurz al-Fihri. It was an attempt to punish a freebooter of the neighbouring region for stealing some of Medinan pasturing camels.114

Analysis of the first seven raids points to the fact that they were carried out under the leadership of the Muhajirun. Their participants were mainly Muhajirun as well. The Ansar were just invited to join them if they wished.115 Waqidi verifies this assertion indirectly when he states that the Prophet did not send any of the Ansar to the expedition of Kharrar (Kharrār خَرَّار) as they had promised that they would protect him in their land alone.116

The clash between the raiders and the raided was inevitable and was just a matter of time.

Artistic rendition of ‘al ‘Uqāb’, flag of Muhājirūn.

The first fight between the Muslims and the Quraysh of Mecca took place when Abdullah bin Jahsh (‘Abdallah bin Jaḥshعَبد اللَّه بِن جَحش) raided a caravan along with a party of eight Muhajirun on the road from Mecca to Taif near Nakhlah. The caravan was accompanied by only four men as it was the sacred month of Rajab. 117 Waqid bin Abdullah (Wāqid bin ‘Abdallahواقِد بِن عَبد اللَّه) from the Muslim side killed one man by name of Amr bin Hadrami (‘Amr bin al-Ḥaḍrami عَمر بِن الحَضرَمى). The party captured two men and one absconded. Later on, a Meccan deputation negotiated the release of the two prisoners. for a ransom of one hundred and sixty dirhams and with the condition that the Quraysh would guarantee the safe return of two Muslims who had separated from the raiding party. One of them was Sa’d bin Waqqas. Prophet Muhammad received the fifth part of the booty from the Nakhlah raid. 118 It was customary in pre-Islamic times that a quarter of booty went to the leader of the tribe. He could use it for personal purposes but had to perform certain functions for the tribe, like looking after the poor and showing generosity.119 This decrease in the leader’s share makes the Prophet, as head of ummah, different from tribal chiefs. 120 Amr bin Hadrami was the first non-Muslim ever killed by the Muslims.

Badr – Muslim’s consolidation at Medina

What started at Nakhlah culminated at Badr. The battle of Badr took place in March 624 CE. 121 Amr bin Hadrami who was killed at Nakhlah was a confederate of Utbah bin Rabi’a (‘Utbah bin Rabī’ahعُتبِه بِن رَبِيعَه) from Abd Shams clan of Quraysh. 122 Now it was his duty to revenge the death. While this matter was still hot in Mecca, Abu Sufyan happened to pass by Medina as head of a commercial caravan accompanied by thirty to forty people. Muslims planned to plunder it. Prophet Muhammad, along with a party of about three hundred and fourteen men, hurried towards the road from Syria to Mecca.123 The caravan is said to be worth five hundred thousand Dirhams and all leading merchants and financiers in Mecca had an interest in it. 124

The Muslims proceeded out of Medina with two separate black flags. One was with Muhajirun and the other was with Ansar. 125, 126 As the flags represented tribes and not the whole Muslim party, it is apparent that the Muslims were still divided on tribal lines and remained so throughout the life of the Prophet. Most of the Prophet’s campaigns carried more than one flag because each flag represented the tribe, not religion. For example, at Ḥunayn each tribe and clan had its own flag. 127. The flags of Aws and Khazraj were green and red in the Jahiliyyah and they kept them as before. 128, 129

Abu Sufyan called for help. Meccans prepared themselves quickly saying ‘do Muhammad and his Companions think this is going to be like the caravan of Ibn Ḥaḍrami?’ Almost every man left Mecca except Abu Lahb who sent a proxy.130, 131

The Muslims focussed all their manoeuvres on finding an opportunity to ambush the caravan, using the spying skills of members of the friendly tribe Johaynah, until such time that they heard the news of Meccans coming for help. The development was worrisome from a Muslim’s point of view. The Prophet convened a pre-war council meeting and asked the opinion of the Ansar, who were in majority, and according to the Aqaba pledge were bound to protect the Prophet only in their own territory. Sa’d bin Mu’adh, the chief of Ansar, was quick to express his willingness to fight along with the Prophet even outside Yathrib. 132 Had Sa’d not expressed such solidarity, it is possible that the Muslims would have retreated that day.

Waqidi’s statement, “Abu Jahl ‘fancied himself’ as a leader”– he was presumably entitled to lead in war only during Abu Sufyan’s absence since Abd Shams were entitled to qiyadah or leadership in war – raises an assumption that Abu Sufyan did not want confrontation at Badr. 133 He took a safer route and got out of reach of Muslims. He then sent a message to the Quraysh to return as the purpose of their coming had been fulfilled. 134 At this juncture a quarrel broke out among the Quraysh. Abu Jahl (‘Amr bin Hishām) was adamant to proceed to Badr, which was the site of the annual fair, to present a show of power so Muslims should respect them in future. 135 But others did not see any point in it. Some started blaming members of Banu Hashim for being the fifth columnists. In the end, many of Banu Hashim and all of Adi (‘Adi عَدِى) and Zuhra (Zuhrah زُهرَه) left.136 The rift in Quraysh’s camp reduced their number from the original nine hundred and fifty to possibly six hundred to seven hundred.137

Waqidi has given the names of all leaders who agreed or disagreed with Abu Jahl’s plan. By looking at their clans it is evident that only Makhzum, Abd ad Dar, Nufail and Amir (‘Āmir عامِر) were in favour of Abu Jahl’s plan in toto. All other clans including Juham, Sahm, Nawfal, Abd Shams and Asad were divided over the issue. Veritably this was the final defeat of clan loyalty in Mecca. After this event, each individual was free to take a stance on whatever he wanted. This process sped up due to the death of so many Meccan leaders at Badr.138

Eighty-three Muhajirun, sixty-one Aws and one hundred and seventy Khazraj participated in the battle of Badr (total of 314). Two were horses and seventy were camels.139

Even superficial browsing of Ibn Ishaq’s description of the events of the battle of Badr makes the causes of Quraysh’s disaster obvious to a reader. Muslims were well informed about the positions of both, the caravan and the reinforcement – thanks to their spying skills. They occupied water resources beforehand which is a prerequisite for winning a war in arid conditions. 140

Memorial monument at site of Badr, 180 km from Medina.141

Lastly, the horror of shedding kindred blood on the Quraysh side and the desire to shed it on the Muslim side was a deciding factor in the battle of Badr, according to Sir William Muir For example, Abu Bakr’s son, who converted long after, told his father that he had intentionally spared him on the day of Badr. Abu Bakr answered that had he got a chance, he would have slain him. Abu Ubayda bin Jarrah killed his father.146 This phenomenon was in stark contradiction to the speech made by Utbah bin Rabi’a immediately before the action, pleading to the Quraysh not to inflict war on the Muslims as they were kinsmen to them.147 In a nutshell the Quraysh were unprepared for a fight at Badr. 148

The battle of Badr was a disaster for Quraysh polytheists. They fled, leaving the bodies of seventy slain behind. 149. Ma’mar agrees that they were seventy slain 150. Ibn Ishaq differs. He gives the number as fifty 151 Those slain in the battle included Utba bin Rabi’a and Abu Jahl. 152 The prophet specifically took pains to identify the body of Abu Jahl to confirm his death. 153 Apparently, he was the only individual among all of the dead who had serious ideological differences from the Prophet. The Muslims could take seventy men as prisoners of war. 154. Waqidi gives confusing figures of both 49 and 70 as the number of prisoners 155. Ibn Ishaq gives this figure to be forty-three 156 The death toll of the Muslims was fourteen. Out of them, six were Muhajirun and eight were Ansar. 157

Prophet Muhammad was apt to declare that triumph had come due to help from Allah, a stance which he maintained for the whole of his life for all the triumphs he secured. 158 Prophet Muhammad never credited himself or anybody else for any victory. At the time of the Hudaybiyah Peace Treaty, the Prophet proclaimed that it was Allah who grants him victory 159

Two prisoners of war were executed. Uqba bin Abi Mu’ayt (‘Uqbah bin Abi Mu’ayt عُقبَه بِن ابِى مُعَيط) of Abd Shams clan was executed because he had composed a verse insulting Prophet Muhammad. 160 Nadr bin Harith (Naḍr bin Ḥārith نَضر بِن حارِث) was executed because he claimed in a speech that his stories about things Persian were as good as those of the Qur’an. 161 They were the first men ever executed on orders of Prophet Muhammad. It is noteworthy that the Prophet did not execute anybody for not believing in him or disagreeing with him or arguing with him, which all prisoners of war of Badr had done and it was the opinion of Umar bin Khattab and Sa’d bin Mu’adh to execute them on these charges. 162

As mentioned earlier, poetry and public oration were main forums of journalism in Arabia during those days and had tremendous power to form public opinion. These executions sent a message all around that Prophet Muhammad would not tolerate publically uttered taunts.

The prophet demanded four thousand silver dirhams for each of the remaining prisoners. 163 Immediate relatives of most of them came to Medina with the asked amount and took them back. A few did not have the demanded money and were set free for less. Still, a few were set free without any ransom as their families did not have any money and nobody came to ransom them.164

One of the prisoners at Badr was Abbas bin Abdul Muttalib, uncle of the Prophet. 165 He had to pay the ransom. 166 Abu Sufyan’s son, Amr (‘Amr عَمرو) was a prisoner of war. Abu Sufyan captured Sa’d bin Nu’man (Sa’d bin Nu’mān سَعد بِن نُعمان) of Ansar who had gone to Mecca for pilgrimage. Sa’d had not suspected that the Quraysh would capture him during pilgrimage as it was not their tradition. Amr was exchanged for Sa’d. 167

Prophet Muhammad got a sword in the booty. Its name was Zulfiqar (Dhu ‘l Faqār ذوالفَقار). The prophet did not have any sword before the battle of Badr. 168 Those who were killed at Badr from the Muslim side also got their share in the booty.169

Aftermath of Badr

Badr sealed the fate of two men. One was Prophet Muhammad, who was the winner of the war and, as a result, his religion was going to be one of the largest religions in the world. Another was Abu Sufyan, the survivor of the war whose progeny was going to rule over the first Islamic state, one of the largest states in the world. 170

Mecca lost a little of its prestige but there was no immediate change in the political situation. Overall, it was seen as just another war by most of the tribes living in the Hejaz. For the Arabs of Hejaz, this battle did not mean that Muslim Medina had replaced Mecca as the chief power in the area. Further tests of Prophet Muhammad’s strength were required before everyone would flock to him from far and near. 171

As far as the Muslim-Mecca relationship is concerned, Quraysh of Mecca learned one thing from these events: ‘Muslims do not believe in the old tribal system of security’. Initially, they had ambushed a caravan and killed a person in the sacred month of Rajab. Then at Badr, they refused to pay bloodwit for the slain, rather slew more people. On their part, Quraysh stopped applying tribal rules to the Muslims. Hence Abu Sufyan did not hesitate from capturing Sa’d bin Nu’man, who had gone to Mecca immediately after Badr for pilgrimage during the sacred month of Zul Hajjah. 172 In reality, after the incident at Nakhlah, Quraysh of Mecca had started considering all Muhajirun as one clan. They were asking for bloodwit from all of Muhajirun at Badr. That was the reason only Utba bin Rabi’a, his son Walid (Walīd وَلِيد) and his brother Shayba came out and challenged a duel at the beginning of the battle. When some of the Ansar responded, they sent them back and asked the Muhajirun to answer the challenge. They did not suspect that the Ansar would launch an all-out attack once the duels were over. Nawfal bin Khuwaylid of the Asad clan, a polytheist fighting in the battle of Badr, expressed it clearly by asking the Ansar why they killed so many of the Quraysh when they did not have any dispute with the Quraysh. 173 Battle of Badr taught them that the Ansar were also part of the same clan. Abu Sufyan knew that taking hostage Sa’d bin Nu’man, one of Ansar, will mean he had captured one of them – the Muslim tribe. The battle of Badr successfully challenged the old security system of the Nomadic Zone and established the need for a new one.

From the Muslim’s point of view, wealth, fame, honour, and power were secured on the day of Badr. 174 Muslims emerged as a ‘sovereign tribe’ in the eyes of others. Quraysh, thereafter, were unable to conduct their trade with Syria through the convenient route that passed between Yanbu and Medina. Instead, they had to use a farther route through Iraq and even that route was under Muslim raids.175

Badr strengthened Prophet Muhammad’s position in Medina. For example, Usayd bin Hudayr (Usayd bin Ḥuḍayr اُسَيد بِن حُضَير), an Ansar from Aws who was not enthusiastic about supporting Prophet Muhammad’s expedition, made excuses as soon as the Prophet returned triumphantly. 176 Ḥuḍayr bin Simāk of the Ashhali clan of Aws remained dominant in the war of Bu’ath and always claimed to be a victor. He was killed by the time of the Immigration 177. His son Usayd bin Hudayr accepted Islam before Immigration and was one of the nuqabā’ but was doubtful about its success. It can explain his absence from the battle of Badr, though he later apologized to Prophet Muhammad for it. 178

Similar is the case of Abdullah bin Unays (‘Abd Allah bin Unays عَبد اللَّه بِن اُنَيس), another Ansar. 179 In the Dhu Amar (Dhu Āmar ذي أمر) expedition, which was carried out after Badr, Prophet Muhammad could muster up four hundred and fifty men, meaning more people were willing to side with Prophet Muhammad. 180

Encouraged by the prestige they gained in the battle, Muslims were bent on getting rid of some local pockets of opposition. Three murders took place in Medina, one after another, each carried out by Muslims.

The only Arab clan still unimpressed by Islam in Medina was Aws Mannat (Aws Mannāt اَوس مَنَّاة). Asma bint Marwan (‘Aṣmāʾ bint Marwān عَصمَاء بِنت مَروان) was from the family of Umayyah bin Zayd of Aws Mannat. She composed verses taunting some of the Muslims.181 A man called Umayr bin Adi (‘Umayr bin ‘Adi عُمَير بِن عَدِى) from Khatma (Khaṭmah خَطمَه), the clan of her husband, entered her house at night and murdered her on orders of Prophet Muhammad and nobody dared to take vengeance on Umayr and the rest of Aws Mannat converted. Her satire, preserved by Ibn Ishaq, was addressed to some men of Ansar mocking them for dishonouring themselves by submitting to a stranger, not of their blood.182, 183

Qaṣr reputed to be of Ka’b bin Ashraf.184

Times in Medina had changed and Asma and Abu Afak were on the wrong side of the time. After their murders, all pagan resistance to Prophet Muhammad at Medina died out. 186, 187. Some Aws and Khazraj never became Muslim. Examples include Abd Amr Abu Amir ar-Rahib (‘Abd Amr Abu ‘Āmir ar-Rāhib عَبد امر اَبُو عامِر الراهِب), who retired to Mecca and participated in the battle of Uhud from the Meccan side 188. He then immigrated to Syria 189. From there, he was involved in the building of a mosque of opposition in Medina later 190. Abu Qays bin al-Aslat is another example, who died Hanif. 191

In September of 624 CE, Ka’b bin Ashraf (كَعب بِن اَشرَف) was assassinated by five members of Ansar fulfilling the wishes of Prophet Muhammad. This Ka’b was from the distant tribe of Tai (Ṭāʾī طاءِى) but he associated more with his mother’s tribe of Nadir and lived in Medina.192 He had gone to Mecca to instigate them against the Muslims and to incite them to invade Medina.193 As he was killed by the clans who were confederates to Nadir, it was considered an internal matter from a tribal law point of view and Nadir did not demand blood money.194

Such measures made it clear to everybody in Medina that Prophet Muhammad was not a man to be trifled with. For those who accepted him as a leader, there were material advantages; for those who opposed him, there were serious disadvantages. 195

After the battle of Badr nomads between Medina and the Red Sea became friendlier to Muslims and the Quraysh could not send caravans through this route anymore. 196 In truth, when the Quraysh marched upon Uhud, it was the Khuza’ah tribe living in the area who passed advance information to Prophet Muhammad. 198 Pagan nomads in the neighbourhood of Medina became readier to accept Islam after the battle of Badr. This is the time when we hear of the earliest converts among them. For example, Du’thur bin Harith (Du’thūr bin Ḥārith دُعثُور بِن حارِث) of Muharib (Muḥārib مُحارِب) clan accepted Islam few months after the battle of Badr. 199

The victory at Badr gave Muslims the boldness to raid tribes other than the Quraysh. After the battle of Badr strong tribes of Sulaym and Ghatafan were raided in the expedition of Qarara al-Kudr (Qarāra al-Kudr قَرارَةُ الكُدر) and a large number of their camels were driven off. 200

The worst pressure came upon the Jewish population of Medina. The Jewish tribe of Qaynuqa was attacked after a trivial dispute that led to the deaths of a Jew and a Muslim. 201 They were besieged for a fortnight. 202 Qunayqa surrendered unconditionally and were allowed to leave Medina along with their women and children, but without their property, on arbitration by Abdullah bin Ubayy to the Prophet. 203 They are said to go to Wadi al-Qura (Wādi ‘l Qura وادى القُرىٌ) and after one month to Adhra’at (‘Adhra’āt عَذرَعات) in Syria. 204, 205 It is worth noting that the total Jewish population in Medina at that time is guestimated to be two thousand adult males. (Seven hundred Qaynuqa, plus six hundred Nadir plus seven hundred and fifty Qurayzah).206 The total Muslim population of Medina then is guestimated to be four hundred and fifty adult males. (This is the number present at Dhu Amar).207 The Jews could have given stiff resistance to the Muslims if they took a united stand on this occasion. The very fact that the other two tribes did not interfere in the matter shows that the Jews were not one consolidated religious community. They were divided into tribes, like all other Arabs of the day. More interesting is the fact that Qaynuqa alone outnumbered Muslims. They did not dare to fight with Muslims. Future events further proved that the Jews of Hejaz had lost their fighting spirit which was mandatory to survive in the stateless nomadic zone. The departure of Qaynuqa was a loss to the Munafiqun. Thereby, Abdullah bin Ubayy, the leader of Munafiqun, lost about seven hundred of his confederates.208 Another confederate of Qaynuqa was Ubada bin Samit (‘Ubādah bin Ṣamit عُبادَه بِن صَمِت). He publically denounced his confederation when tensions with Qaynuqa started growing. 209

The success against Qaynuqa opened the way to expel other Jewish tribes. Almost six months after the battle of Badr, Prophet Muhammad went to the settlement of Nadir to demand their contribution towards the blood money that was to be paid to the tribe of Amir bin Sa’sa’ah (‘Āmir bin Ṣa’ṣa’ah عامِر بِن صَعصَعَه) for their two men killed by a Muslim survivor of the incident of Bir Maona (Bi’r Ma’unah بِءِر مَعُونَه).210, 212, 213. They asked him to wait while they prepared food for him. After a while, the Prophet left the place and told his Companions that the Nadir were planning to murder him. 214 Watt thinks that the Prophet’s suspicion could be genuine on the ground that they had not digested the assassination of Ka’b bin Ashraf. In any case, the Prophet sent them an ultimatum to leave Medina within ten days, though they were entitled to keep their estates. The Nadir were reluctant to meet the demand as they had received reassurance from Abdullah bin Ubayy of support. The Prophet besieged them. The Nadir lost their heart after fifteen days of siege when the Muslims started destroying their palm trees. They offered a settlement. This time the Prophet gave them harsher conditions of leaving both the town and their agricultural property and their arms. They were allowed to take their women, children and their movable property with them. They went to settle in Khaybar where they had got estates. The farms confiscated from them were distributed to the Muhajirun, relieving the Ansar from the duty of hospitality towards them. Two poorer members of Ansar got farms as well. 215 The Prophet himself got an orchard. 216 This was the first real estate the Prophet owned. According to Baladhuri, it was only after this acquisition that the Prophet allocated ration to his wives.

Waqidi reports that the Qurayzah flatly refused to help the Nadir on this occasion. 217 They entered into a pact with the Muslims regarding this matter. 218

Now, Prophet Muhammad turned his attention toward establishing a land title register. Ansar already possessed properties in Medina. Prophet Muhammad confirmed them in their ownership. The newly acquired properties by the Quraysh immigrants got legal support from Prophet Muhammad. 219, 220 Watt believes that at this point Prophet Muhammad not only established charters defining land rights, which no doubt made it easier in the future to deal with land disputes, but he also dealt with theft harshly. 221

In summary, the Muslims consolidated their political hold on the township of Medina in the few months that followed the battle of Badr.

Further events – Uhud

The seeds of Uhud (Uḥud اُحُد) were sown on the day of Badr. Quraysh polytheists had multiple reasons for war: Their duty to avenge their dead; the need to secure their trade route to Syria; and their wish to restore their political prestige. On the other hand, Muslims were not willing to accept responsibility for those Quraysh who were killed at Badr by paying the blood money and had to defend their conviction with sword. War was inevitable.

The effect of Badr in Mecca was quite opposite to that in Medina. It was now clear to the Quraysh polytheists that Prophet Muhammad was a serious threat. 222 With most of the prominent leaders of Meccan polytheists now gone, all eyes were fixed on Abu Sufyan bin Harb of Abd Shams clan. 223

In the words of Hind bint ‘Utbah, the wife of Abu Sufyan and the daughter of Utba bin Rabi’a:

Give Abū Sufyan a message from me,

If I meet him one day I will reprove him.

‘twas a war that will kindle another war,

For every man has a friend to avenge. 224

Abu Sufyan was a distant cousin of Prophet Muhammad. 225 He was a mild but astute man who loved his people exceedingly. 226 He was a man of means and as a successful businessman, he owned property not only in Taif but also in foreign lands like Syria. 227

Abu Sufyan forbade mourning for the dead of Badr. This was ostensible to prevent Muslims from gloating over their plight and to avoid dissipating the energies of the Meccans. 228 If he had not done this, there could have been a complete collapse of morale in the town. 229 He also pledged to devote all the profit made by the trade caravan that could safely return to Mecca, to equip a force to be sent to Medina. 230

After the battle of Badr Quraysh’s trade caravans to Syria, their lifeline had come to a complete halt. Safwan bin Umayyah (Ṣafwān bin Umayyah صَفوان بِن اُمًيَّه), the new leader of Makhzum clan after Abu Jahl, and in all likelihood rival to Abu Sufyan, tried to take a caravan by a route that passed east of Medina. Muslims, under Zayd bin Haritha, captured merchandise worth a hundred thousand dirhams. The men in charge of the caravan escaped. 231, 232

Politically humiliated and financially strained, the Quraysh of Mecca started communicating with possible allies. They sent embassies to the Thaqif of Taif. They also summoned Ahabish (Aḥābīsh اَحابِيش), the black troops. 233 Ahabish were a collection of small tribes or clans who had committed themselves to help the Quraysh in pre-Islamic times near a black mountain, hence their name. Its leading groups were Harith bin Abd Manat (Ḥārith bin ‘Abd Manāt حارِث بِن عَبد مَناة) and Bakr bin Abd Manat (Bakr bin ‘Abd Manāt بَكر بِن عَبد مَناة) clans of Kinanah. Smaller clans like the Mustaliq clan of Khuza’ah and the Hun (Hūn هُون) clan of Asad and the tribe of Hudhayl were part of Ahabish as well. 234 It was only the Ahabish who responded to their call and were present at Uhud. 235

The Quraysh financed their campaign of Uhud against the Muslims for five hundred thousand Dirhams. 236

The Battle of Uhud took place on March 23, 625 CE. 237 The Meccan army was three thousand in number.238 Muslims came out of the township of Medina to tackle the Meccan army. Waqidi tells that Abdullah bin Ubayy, along with one-third of the army returned to Medina, with a pretext that the Ansar were bound to protect the Prophet only within the confines of Medina. 239 The people who followed him were three hundred in number.240 So, the total number of remaining Muslim combatants was six hundred.

Only the chiefs of Quraysh had brought their wives along to Uhud. Out of them Abu Sufyan and Safwan bin Umayyah brought two each, indicating that they were respective leaders of rival factions. Ikrama bin Abu Jahl and Amr bin As brought one wife each.241 They were still young and not on par with others.242

According to Ibn Ishaq, Uhud was a day of calamity for the Muslims. 243 He gives number of Muslims who died that day at sixty-five. 244 Ma’mar gives a score of seventy. 245 Waqidi’s figure is seventy-four. 246 Out of them only four were Muhajirun, meaning it was a larger calamity for the Ansar. 247

A piece of poetry composed by Abdullah bin Ziba’ra (‘Abdallah bin Ziba’rā, عَبد اللَّه بِن زِبَعرىٌ) a Meccan polytheist, immediately after the war and preserved by Ibn Ishaq, sheds light on the plight of the Muslims:

They wished that the earth would swallow them,

Their stoutest hearted warriors were in despair.

When our swords were drawn they were like

A flame that leaps through brushwood.

On their heads we brought them down

Bringing swift death to the enemy.

They left the slain of Aws with hyenas hard at them and

Hungry vultures lighting on them.

The Banu Najjār on every height

Were bleeding from the wounds on their bodies.

But for the height of the mountain pass they would have left Aḥmad dead,

But he climbed too high though the spears were directed at him.

As they left Ḥamza dead in the attack

With a lance thrust through his breast.

Nu’mān too lay dead beneath his banner,

The falling vultures busy at his bowels. 248

Drawn by Hamidullah.249

The battle of Uhud introduced three new faces to the regional politics. One was Ikrama bin Abu Jahl (‘Ikramah bin Abū Jahl عِكرَمَه بِن ابُو جَهل) of the Makhzum clan, who lead the right wing of the Meccan army. The other was Khalid bin Walid (Khālid bin Walīdخالِد بِن وَلِيد ) of the Makhzum clan, who was the head of the left wing. The last was Amr bin As (‘Amr bin ‘Āṣ عمرو بن العاص) of the Sahm clan of Quraysh, who led the cavalry of the Meccan army. 251 Out of them, the one who rose to prominence at the occasion of Uhud, was Khalid bin Walid. It was he, who is credited with finding an opportunity to attack the Muslims from the rear. And this was the attack that created calamity for the Muslims.252

Watt believes that indiscipline and love for booty among the Muslims, which is described by early Islamic sources as the main reason for the disaster at Uhud, could be due to swollen number of the Muslim camp that had happened after the battle of Badr when a lot of people joined Islam for greed.253

Ibn Ishaq does not give any clear reason why the Meccans retreated without routing the Muslims out completely on that day. Waqidi notes a scene of disagreement in the Quraysh camp by the end of the war. Safwan bin Umayyah was of the view that they had achieved enough and should return home while Abu Sufyan along with Amr bin As were of opinion that they should profound their advantage by attacking Medina. 254 Safwan discouraged further attacking Medina on the ground that the Muslims had not followed them up after their defeat at Badr. 255 Watt thinks that Safwan was afraid of any glory being given to Abu Sufyan.256 Ma’mar gives another view. He tells us that after the battle Abu Sufyan proclaimed that he had got one Muslim killed for one Quraysh slain at Badr.257 Ibn Sa’d goes with this version. He says the Quraysh declared themselves satisfied, having killed an equal number of foes to the slain Quraysh at Badr. 258

A show of power by a march to Harma al Asad (Ḥamrā’ al Asad حَمراء الاَسَد) on the next day by the Prophet and his Companions, almost all of whom were injured at that moment, would have bolstered the morale of Muslims. 259 Quraysh was not afraid of this gesture. As a matter of fact, Abu Sufyan sent a message to Prophet Muhammad that they could return and fight again if Prophet Muhammad aspires so. It was Safwan bin Umayyah who insisted on returning. 260

Dirar bin Khattab (Ḍirār bin Khaṭṭāb ضِرار بِن خَطَّاب), Umar bin Khattab’s brother had participated in the battle from the Meccan side. He discloses that the polytheists wished before the war that the Muslims come out of the town to confront them in the open so they could defeat them with help of their larger number. They were afraid that if the Muslims remained fortified in their fortresses they would return empty-handed.261, 262

Aftermath of Uhud

Watt is definite that the Muslims had to answer pungent questions in the aftermath of Uhud.263 Waqidi gives the impression that such questions were really asked. 264 Groups of people who were not on good terms with the Prophet and the Muslims were still living in Medina. Abdullah bin Ubayy had engineered a show of power as late as the start of Uhud when he returned to Medina along with three hundred of his companions. 265 Despite the existence of opposition, we do not hear of any incident immediately after the battle of Uhud whereby Muslims were physically challenged within Medina. Nor do we hear of any attack from the nomadic tribes living in the vicinity of Medina. After analysing the situation, Watt concludes that the Muslims could save their face and impact of the disaster on their overall situation was not that negative.266

One observation is definite. Both Muslims and the Meccan Quraysh did not yet feel compelled to sit together, balance out the dead, take blood money for outstanding slain, and seal the peace, as Arabs used to do after protracted wars. Passions of revenge continued. During a show of power at Hamra al Asad, Muslims could get hold of Amr bin Abdullah (‘Amr bin Abdallah, عَمرو بِن عَبد اللَّه), a Meccan polytheist of Jumah clan, who was asleep separate from the main body of Meccans. 267 Muslims executed him.268 Incidence of Raji (Rajī’ رَجيع) took place immediately after the battle of Uhud, whereby Adal (‘Aḍal عَضَل) and Qara (Qārah قارَة) families of Hun clan of Asad treacherously captured two Muslims and sold them to the Meccan Quraysh who killed them for revenge of their dead ones. 269, 270

As hostilities persisted, Meccans started wooing the tribes around Medina to be confederate with them against Prophet Muhammad and on the other hand Prophet Muhammad’s strategy was to prevent them from joining the Quraysh.271 A bigger confrontation and a bigger war were looming.

Last defensive war – Khandaq

The battle of Khandaq, (the battle of the trench), started on March 31, 627 CE and lasted about a fortnight. 272 It is known that the Meccan Quraysh could still not carry trade caravans after Uhud. Furthermore, Muslims were not behaving like a defeated party. They presented themselves at the annual fair of Badr, one year after the battle of Uhud, to answer the challenge of polytheists of Mecca but none of the polytheists were interested in showing up there. 273 Muslims had expelled the Nadir to Khaybar by that time. They were keen to repossess their lands in Medina.274 It was the Jews of Nadir who instigated the tribe of Ghatafan that they would pay them half of their crop if they join the Quraysh to attack Medina. 275 This tradition, if true, provides proof that the Jews were rich enough to buy mercenaries but timid enough not to fight themselves for their cause. They were also Nadir who coaxed the tribe of Sulaym for their seven hundred warriors. Sulaym were also confederates of Harb bin Umayyah (Ḥarb bin Umayyah حَرب بِن اُمَيَه), father of Abu Sufyan. Alliance building was in the air. Presumably, Muslims tried to obstruct alliance formation with force because early Islamic sources mention that the Muslims had once marched against Ghatafan before the battle of Khandaq but no fighting took place.276 This was the occasion when Muslims offered the prayer of fear (ṣalāt ul-Khawf صَلاة الخَوف) for the first time in their history. The tribe of Asad and Ghifar (Ghifārغِفار) clan of Kinanah were confederates of the Jews.277 They were contacted as well.

Ultimately, three armies consisting of a total of ten thousand men descended upon Medina.278 Tribes involved were Quraysh along with their Ahabish; Sulaym; Asad bin Khuzaymah; and Ashja’, Fazarah (Fazārahفَزارَه) and Murrah clans of Ghatafan.279 All the tribes in the grand confederation lived around Mecca and Medina. Faraway tribes were neutral to the feud between Muslims and Quraysh. Ashja’, not all of them, were four hundred and were led by Mas’ud bin Rukhayla (Mas’ud bin Rukhaylah مَسعُود بِن رُخَيلَه). Sulaym were led by Sufyan bin Abd Shams (Sufyān bin ‘Abd Shams سُفيان بِن عبد شَمس). Fazarah clan of Ghatafan, numbering one thousand, was led by Uyayna bin Hisn (‘Uyaynah bin Ḥiṣnعُيَينه بن حِصن). Murrah clan of Ghatafan, numbering four hundred, was led by Harigh bin Awf (Ḥarīgh bin ‘Awf حَرِيغ بِن عَوف). Asad bin Khuzaymah tribe was led by Tulayha bin Khuwaylid (Ṭulayḥah bin Khuwaylid طُلَيحَه بِن خُويلِد). The Quraysh, led by Abu Sufyan and joined by Ahabish, were four thousand strong. Abu Sufyan was the supreme commander. 280 They descended when it was bitter cold and crops had been harvested, so there was nothing in the fields for their horses and camels. 281, 282 It means they were foreseeing a swift action. The target, as stated by Abu Sufyan later, was to annihilate Prophet Muhammad and the Muslims once and for all.283

Commemorative sign at the reputed site of war of Khandaq.284

Ibn Ishaq and Waqidi both put the Muslim’s number at three thousand.292 Watt thinks they are probably talking about the whole population of Medina including Qurayzah who seem to Watt to have tried to remain neutral. 293 Ya’qubi, a late source, gives the number of Muslims at seven hundred.294 Ya’qubi’s figure appears to be more realistic if we keep in mind that the true followers of Prophet Muhammad were only six hundred at the time of the battle of Uhud. Ya’qubi might have excluded the Munafiqun and the Qurayzah and other splinter groups from his figure.

The trench proved successful in halting the invasion. Procopius’s observation that the Arabs were incapable of storming the weakest kind of barricade has already been mentioned. 295. In worlds of invading army men, ‘this is a device which Arabs have never employed’. 296 Enemy was compelled to lay down siege. A war of nerves started. The two armies were eyeball to eyeball with just a trench separating them. Muslims were nervous that they would not be able to fight with such a large foe if it successfully crosses the trench. Confederacy was frustrated that an unforeseen device was failing their whole scheme. 297 Both parties tried to outmanoeuvre each other. Prophet Muhammad tried to break away Ghatafan from the Quraysh by offering them one-third of Medina’s date crop. 298 Their leader Uyayna bin Hisn did not accept the offer. He wanted half of the crop instead of one-third. The Ansar disagreed with Uyayna’s response and said rather they would give him a sword. 299 Quraysh, on their part, through Huayy bin Akhtab (Ḥuyayy bin Akhṭabحُيي بن أخطب) of Nadir, tried to persuade the Qurayzah to open the second front against the Muslims from the rear. 300 In the end Muslims succeeded in creating mistrust among the invading fractions through their agent Nu’aym bin Mas’ud (Nu’aym bin Mas’ūd نُعَيم بِن مَسعُود).301

An exceptionally prolonged winter that year and lack of fodder broke morale of the besieging army. 302 One night, a strong wind proved to be the last straw on camel’s back. First Abu Sufyan, along with the Quraysh, decided to retreat. He did not even bother to consult the Ghatafan. Then Ghatafan and others did not see any point in clinging on and returned. 303

Six Ansar and three Meccan Quraysh were killed in skirmishes. 304

Aftermath of Khandaq

The battle of Khandaq proved to be a fiasco for the grand confederacy of Quraysh. Despite pre-war diplomatic efforts and financing a huge campaign, they could not achieve anything. Abu Sufyan doesn’t appear to play any role in any Muslim-Quraysh dispute after the battle of Khandaq. Not even during the events of the Hudaibiyah Peace Treaty. It means he had made up his mind that the Meccans were not capable of fighting with Prophet Muhammad and had become content with the loss of Quraysh’s glory and trade and a lower standard of living for the Quraysh.305 Ikrima bin Abu Jahl became more prominent after the battle of Khandaq in place of Abu Sufyan. It was he who negotiated with the Jews during the siege, and it was only he who, along with a handful of Quraysh, could cross the trench, though he was fought back.306

Muslims became bolder in ambushing Quraysh caravans. Waqidi mentions that one Quraysh caravan that was bound to either Syria or Iraq immediately after the battle of Khandaq, carrying silver, was captured by Muslims.307 Actually, Quraysh lost their trade with Syria and along with it their wealth and prestige forever. The Muslims were in a position to attack Mecca at any time to try to annihilate them as they had tried to annihilate Muslims in the past. 308

Prophet Muhammad had been a spiritual and political leader so far. Now he emerged as a successful general. And gradually he rose to become more of a statesman. We see that before the battle of Khandaq Prophet Muhammad’s all efforts were to counter Quraysh. Now, knowing that the Quraysh were spent up force, he started thinking of expanding his appeal to other Arab tribes.309

The Battle of Khandaq proved to be a turning point after which the Muslims started raiding tribes other than Quraysh. Some Muslim raids were against the nomadic tribes of Asad and Tha’labah (ثَعلَبَه) clan of Ghatafan, who had taken part in the confederacy of Khandaq. 310 One expedition was against Bakr bin Kilab (Bakr bin Kilāb بَكر بِن كِلاب) clan of Amir bin Sa’sa’ah. 311 Amir bin Sa’sa’ah were genealogically part of Hawazin but had grown into a tribe on their own merit. As part of Hawazin, they were confederates of the Quraysh, yet they did not participate in the confederacy of Khandaq.

Expedition to far off tribes like Judham (Judhām جُذام) and the distant town of Dumat al-Jandal (Dūmat al Jundal دُومَةُ الجَندَل) by Abdur Rahman bin Awf became possible only after battle of Khandaq. 312 It was the first expedition the Muslims carried out to such a faroff place. Its aim was to bring people living beside the road to Syria nearer to Islam, to block Quraysh’s trade further, and to start Medinan trade. 313 Around this time, Zayd bin Haritha went to Syria along with other merchants and with money from the Companions of the Prophet in first ever trade mission from Medina. Unfortunately, he got looted on the way.314 Still, much was to be done to secure Medina-Syria route.

The people of Arabian Peninsula, though scattered over the large land mass, were definitely not aloof to each other. The news of failure of the Meccan Quraysh might have spread far and wide. They might have lost their prestige for ever. This is the time Islam started making inroads in far off Yemen (see below)

Lastly, after battle of Khandaq, Muslims could eliminate the last vestiges of opposition in Medina. Abdullah bin Ubayy and his hypocrites were reduced to ineffective opposition. The Muslims eliminated the Qurayzah as well.

Elimination of Qurayzah

The dust of khandaq had still not settled when the Prophet attacked Qurayzah.

The Prophet had made a contract with all Jews of Medina on arrival that they would not support enemies of Prophet Muhammad; rather, they would support his attack against them. 315 Sticking to the contract, the Qurayzah not only borrowed their instruments from the Muslims to dig the trench but also joined them in its digging. 316 Later, during the siege, they became double minded. Their leader, Ka’b bin Asad (Ka’b bin Asad كَعب بِن اسَد), tore the contract he had written with Prophet Muhammad on instigation of Huyayy bin Akhtab of Nadir who was sent by Abu Sufyan. 317 Huyayy had called them to annul the agreement with Prophet Muhammad and open a war on the Muslims from behind, so they had to abandon the trench so the confederation troops could cross it. They annulled the agreement but couldn’t muster courage to open second front. 318 According to Waqidi, they were doubtful whether Muslims would ever be defeated at the hands of the confederation. 319

While facing a big army, halted only by trench and consistently trying to cross it from any weak point, the possibility of attack from behind by Qurayzah made the Prophet particularly distressed. 320 Not only this, Muslims became worried about the safety of their women and children who were kept in fortresses in Medina. 321

After threat of outside invaders was over, war against Qurayzah was inevitable. Muslims were in good spirit. Total number of Qurayzah was only seven hundred and fifty.322 Muslims felt if they did not tackle them properly now, they could provide anchoring point inside Medina for any invading force in future.

Qurayzah retired to their stronghold and did not fight back with vigour, though their leader ka’b bin Asad encouraged them to do so.323 During negotiations they offered to surrender on the same conditions that were offered to Nadir but the Prophet insisted on unconditional surrender. In Ma’mar’s version, the Qurayzah refused to surrender to the judgement of Prophet Muhammad. They rather agreed to surrender to the judgement of Sa’d bin Mu’adh. 324 The reason why they were so reluctant to surrender to the judgment of the Prophet could be that Abu Lubaba (Abū Lubābah اَبُو لُبابَه), an Ansar, had signalled to the Qurayzah that they would be killed by Prophet Muhammad.325 Two Ansar died during the siege of the Qurayzah.326

Some clans of Aws were Qurayzah’s confederates and they requested that the Prophet Muhammad to pardon them. Prophet Muhammad suggested to them that the fate of Qurayzah should be decided by one of the leading men of Aws, namely Sa’d bin Mu’adh who, by this time was struggling with grievous wounds he got in the battler of Khandaq. Aws swore to abide by Sa’d’s judgement. He decreed to put all the Qurayzah men to death and to sell their women and children as slaves. The sentence was duly carried out. The number executed could be six hundred. 327, 328. A member of ‘Abd al-Ashhal clan of Aws, Sa’d bin Mu’adh had emerged most prominent leader of the Aws in the aftermath of the war of Bu’ath. He accepted Islam very early and wholeheartedly, and fought at Badr and remained loyal. Ibn Ishaq believes that it was his conversion which led to general conversion in Medina 329. Prophet Muhammad kept an esteemed opinion about him his whole life. It is evident from the tradition that the Prophet remembered him with good words during the Tabuk expedition 330, 331 Watt believes that this harsh punishment was necessary to convince the clans of Aws, who were still sticking to old alliances, that they have been annulled and currently these clans were part of the ummah. 332 In fact, each clan of Aws was allotted two condemned to execute so the blood of Qurayzah should be on all of them. The Muslims divided their lands among themselves. 333

After Qurayzah, the Jewish opposition in the town ceased to exist, though some Jews like Abu Shahm (Abū ‘sh-Shaḥm اَبُو ااشَحَم) continued living in the town. 334 He and some other Jews were still in Medina when the Muslims returned from the battle of Khaybar. 335 Abu Shahm converted later on but others kept their faith.336 The Jews of Medina even participated in the campaign of Tabuk from Muslim side.337

After doing away with the Qurayzah, Prophet Muhammad sent a few Muslims under the leadership of Abdullah bin Atiq (‘Abd Allah bin ‘Atīk عِبد اللَّه بِن عَتِيق) to kill Sallam bin Abu Huqayq (Sallām bin Abu’l Ḥuqayq سَلَّام بِن حُقَيق), a Jew of Nadir living in Khaybar, who had played a significant role in forging the alliance of tribes against the Muslims at the battle of Khandaq. Abdullah bin Atiq did his job successfully. 338 None of Nadir or anybody else at Khaybar could demand blood money. They were too weak to do that.

With Qurayzah finished, Medina became a true state which had a ruler, and certain rules to be followed by everybody including the ruler himself, and a legal mechanism was needed to impose the rules. 339 Nobody had to take arms personally to protect his life, property or honour. The time span from the Immigration to the establishment of the city-state in Medina is almost five years. 340

The institution of the state developed very early in the history of mankind. The Ubaid period of Mesopotamia is associated with state formation. Eridu was a temple city as early as 5300 BCE. But later on, Uruk in Mesopotamia established itself as a true state with documented rulers around 3600 BCE. Alulim is said to be the first king. Abydos in Egypt is another earliest state. 341

Ruins of Uruk: 30 Km east of modern Samawah, al-Muthanna, Iraq.342

Since the very inception of the state, which incidentally happened in the Arabian Peninsula, the state has deteriorated to non-existent in many parts of the world at many different times. But each time the ensuing anarchy failed to lead human society toward prosperity and satisfaction. And each time people were compelled to reorganize themselves in the state earlier or later. The establishment of the state in Medina was the first nail in the coffin of anarchy that had been prevailing in the nomadic zone of Arabia since the demise of the last states a few centuries ago.

Peace with Mecca – Hudaibiyah

When Prophet Muhammad started the march towards Mecca in March 628, one year after the battle of Khandaq, he was in pilgrim’s grab and was carrying seventy sacrificial animals to convince the Quraysh of Mecca that his intention was really to perform umrah (little pilgrimage ‘umrah عُمرَه).347 He invited Juhaynah, Muzainah and Bakr to join him but they refused to participate.348 The only reason of their refusal was no prospects of booty.349 Still there were about fourteen hundred people with the Prophet.350 They were Muhajirun and Ansar, and few individuals of Juhaynah, and Khuza’ah.351, 352 Analysis of Waqidi’s narration of the event gives an impression that the procession was lightly armed, armed enough to defend itself in case of dire need, but not armed enough to threaten anybody.353

The Quraysh took it offensive that the Prophet wished to enter Mecca without their prior permission.354 They called Ahabish for help.355 Some Thaqif also joined them.356 They came out of Mecca to camp at Dhu Tuwa (Dhū Ṭuwa ذي طُوىٌ) and sent their cavalry under Khalid bin Walid to tackle the Muslims.357 The cavalry could not trace the Muslims as they were using an unusual route to avoid an encounter. 358 Ultimately, It was the Ahabish who halted the Prophet’s march at Hudaibiyah (Ḥudaybiyah حُدَيبِيَه). 359 So the Muslims camped at Hudaibiyah outside Mecca.360

The Quraysh were suspicious of the intentions of the Muslims whereas Prophet Muhammad was adamant that he intended to perform umrah peacefully. None of them wanted war. Donner argues based on circumstantial evidence that the food supply of Mecca was compromised as a result of the blockade of Mecca by Prophet Muhammad. It plunged them into famine and was one factor of Fath Mecca. 361 Negotiations were inevitable. Quraysh sent the leader of Kinanah, chief of Ahabish, Hulays bin Alqama (Ḥulays bin ‘Alqamah حُلَيس بِن عًلقَمَه) as their emissary to the Prophet. 362 He got convinced that the Prophet was true to his intentions and told the Quraysh of his opinion to let Prophet Muhammad in. Quraysh remained suspicious. Angrily, he threatened the Quraysh with the withdrawal of his Ahabish from Mecca. Then they sent Urwa bin Mas’ud (‘Urwa bin Mas’ūd عُروَه بِن مَسعُود) of Ahlaf (Aḥlāf اَحلاف) clan of Thaqif to the Prophet.363 And many other emissaries were sent. Muslims also sent Uthman bin Affan as an emissary to Mecca. 364 Final emissary from Mecca, who could seal the treaty was Suhayl bin Amr (Suhayl bin ‘Amr سُهَيل بن عمرو). 365

The treaty was: “In thy name O Allah. This is what Muhammad bin ‘Abdallah made with Suhayl bin ‘Amr: They have agreed to lay aside war for ten years during which men can be safe and refrain from hostilities on the condition that if anyone comes to Muhammad without permission of his protectors, he will return him to them; and if anyone of those with Muhammad comes to Quraysh they will not return him to him. We will not show enmity one to another and there shall be no secret reservation or bad faith. He who wishes to enter into a bond and agreement with Muhammad may do so and he who wishes to enter into a bond and agreement with Quraysh may do so.…….. you must retire from us this year and not enter Mecca against our will, and next year we will make way for you and you can enter it [Mecca] with your companions and stay there for three nights. You may carry a rider’s weapons, the swords in their sheaths. You can bring in nothing more.”366

Prophet’s Companions did not doubt that the purpose of the march was to occupy Mecca and they were depressed by this peace treaty. 367 The prophet had to convince them that it was a correct decision in given circumstances. Actually, the disagreement between the Prophet and his prominent Companions had started from the very onset of the march, when they wished to go fully armed but the Prophet prohibited it.368 They continued to insist on entering Mecca forcefully throughout the process of negotiations. 369 The prophet was fully aware that the Quraysh were injured and exhausted from war, but he still wished to offer them a period of protection if they wished so. 370 The Companions perceived conditions of the agreement humiliating and resentment against it was so great that nobody responded when the Prophet called the next day to sacrifice animals without circumambulating Ka’ba, get their heads shaved and return. 371, 372

Analysing the peace treaty Watt writes that the Prophet’s intention from this march was to show the Meccans that pilgrimage and hence Mecca was still the center of Islam. He approached Meccan polytheists with an olive branch to show them that he wished to be friendly with them. Prophet Muhammad had the power to enter Mecca forcefully and the compromise saved the Quraysh’s face. 373 It is worth noting that Safwan bin Umayyah, Suhayl bin Amr and Ikrama bin Abu Jahl were more active in negotiating with the Prophet. 374 Abu Sufyan made himself absent. 375

Unconditional obedience to the Prophet

A very important incident took place on the sidelines of Peace Treaty of Hudaibiyah. It is called the Pledge of Ridwan (Ba’t ur-Riḍwān بَعَتُ الرِضوان). 376 Politically, it was as significant as the Pledge of Aqaba. It happened in the backdrop of unverified news that Uthman bin Affan, Prophet’s emissary to the Quraysh, was slain by them. Ibn Ishaq reports that the Prophet took pledge from his people that they would not run away.377 Ibn Ishaq’s report sounds unconvincing. These were the people who had fought along with the Prophet many times and had accompanied him to Hudaibiyah, whereas many others had plainly refused to do so. Their loyalty towards Islam was undoubted by that time. Prophet would not have to take pledge of fighting from them. Waqidi, on the other hand, gives exact wording of the pledge, ‘O Messenger of Allah, I pledge allegiance to you and to what you desire’. 378 After analysing many events before the Pledge of Ridwan and after it, Watt concludes that the Muslims were bound to obey Allah and not the Prophet per say before it, as far as politics was concerned. If the Prophet presented a proposal in a pre-war council, Muslims had a right to question him if it was his proposal or Allah’s instructions. Now they pledged to follow his commands without any hesitation.379