Historical sources are materials that are used to construct history. Basically, they are divided into primary and secondary sources. Primary sources are contemporary with historical events. Examples are coins, inscriptions, buildings, diaries etc. Secondary sources are records produced in light of primary sources. Examples will be a text written after the events or a painting about an event drawn afterwards. Whenever a new primary source comes to light it is treated like a treasure by historians. It provides first-hand testimony that is not distorted by transmission. Still, historians have to largely depend upon secondary sources as primary sources are always scarce. 1

Historical sources, both primary and secondary, for the pre-Islamic history of Arabia are particularly scant.

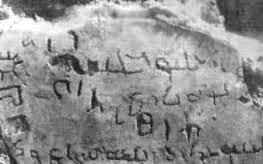

4th century CE rock inscription in Arabic from Jabal Rāmm (جبـل رام), Modern day Jordan. 2

Satellite pictures of Saudi Arabia have shown the presence of almost two thousand archaeological mounds still to be excavated. 4 This kind of evidence is supported by surveys performed by the Saudi Commission of Tourism and Antiquities which give the number of such sites to be more than ten thousand. 5 Their digs over time will uncover more historic sources of pre-Islam and Islam and will definitely enrich our knowledge of Arab history.

Another source of pre-Islamic history is pre-Islamic Arabic poetry. It is a body of poetry that was mainly composed in the 5th and 6th centuries and has survived the atrocities of time. 6 It is considered a reliable source of information by a majority of historians. 7 Ibn Qutayba (d. 889 CE) notes a poem and attributes it to Tubba’, the king of Yemen in pre-Islamic times. 8. Now archaeologists have discovered this poem inscribed on a rock face near Mecca in modern Saudi Arabia. The inscriber has taken pains to write down the year of inscription and that is 717 CE. 9. It simply means that what Ibn Qutayba picked out of oral traditions in circulation, was not a creation of his time. The oral tradition existed at least one and three-quarter centuries before the writings of Ibn Qutaybah. Hoyland comments that this discovery gives ‘a little push to the idea that the mass of the material that we have ostensibly going back to pre-Islamic times, in particular a vast wealth of poetry, does genuinely belong to that period”. 10. A rock inscription discovered at ‘En ‘Avadat in present-day Israel and guessed to have been written not later than 150 CE contains two lines of rudimentary Arabic poetry. 11 The inscription further strengthens the hypothesis that Arabic poetry as a medium of communication originated in the second century CE and that Arabic poetry is pre-Islamic.

There are extant writings of non-Arab contemporary scholars, for example, Byzantine or Sassanian writings. Whenever they mention Arabs or Arabia, the writing becomes indispensable as far as the history of Arabia is concerned.

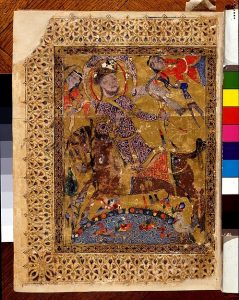

Front page of Kitāb al Aghani Commonly cited early Islamic source. 12

Lastly, indigenous institutions and fundamental patterns of social behaviour in pre-oil Arabia had hardly changed from the earliest historical times. 15. Sociological studies of pre-oil Arab culture find similarities between current and past practices. These are another source of understanding the thought process of pre-Islamic and early Islamic Arabs. 16

End Notes:

- For further reading on sources and their significance see: Sreedharan, E. A Textbook of Historiography 500 BC to AD 2000. New Dheli: Orient Longman, 2004.

- Grohmann dates it from 328 CE to 350 CE (Adolf Grohmann, Arabische Palaographie. II. Teil. (Graz: Bohlau in Kommission, 1971), Vol 94, P 14, 16). Translation: I rose and made all sorts of money; which no world-weary man has [ever] collected; I have collected gold and silver, I announce it to those who are fed up and unwilling (J. A. Bellamy, “Two Pre-Islamic Arabic Inscriptions Revised: Jabal Ramm And Umm Al-Jimal,” Journal Of The American Oriental Society, 108 (1988): 369 – 372).

- “DASI: Digital Archive for the Study of Pre-Islamic Arabian Inscriptions”. University of Pisa. Accessed March 19, 2017, http://dasi.humnet.uipi.it/.

- Asher Moses. “Aussie desktop archaeologist’s Major Saudi sighting”. The Sydney Moring Herald, Feb. 7, 2011.

- Ali I. Al-Ghabban, “The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and its Heritage,” in Roads of Arabia, ed. ‘Ali ibn Ibrāhīm Ghabbān, Beatrice Andre-Salvini, Francoise Demange, Carine Juvin and Marianne Cotty, (Paris: Louvre, 2010), 35.

- Robert G. Hoyland. Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam (New York: Routledge, 2001), 251.

- Taha Husain and Magoliouth both are of view that pre-Islamic poetry is actually a post-Islamic innovation. (See: Ṭaha Ḥusayn, Fi’l-shi’r al-Jahili, Cairo: Dār al Ma’arif, 1925. AND D. Margoliouth, “The Origins of Arabic Poetry”, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, (1925): 417 – 449). Later scholars view it as pre-Islamic. (For example, see: M. Zwettler, The Oral Tradition of Classical Arabic Peotry: Its Character and Implications, (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1978): 12 – 14). The question of which portion of it is pre-Islamic and which one is post-Islamic has still not been settled. Certain scholars consider pre-Islamic Arabic poetry truly ‘pre-Islamic’, but they challenge its reliability as a source of history. See: Jonathan A.C. Brown, “The Social Context of Pre-Islamic Poetry: Poetic Imaginary and Social Reality in the Mu’allaqat,” Arab Studies Quarterly 25, no.3 (2003): 29-50.

- Sa’d bin ‘Abd al ‘Azīz al-Rāshid, Kitābāt Islāmiyya Min Makkah al-Mukarramah, 1995, Riyad., (Saudi Arabia): 60 – 66.

- Muḥammad bin ‘Abd al-Raḥmān Rāshad al-Thenyian, Nuqūsh al Qarn al-Awwal al-Mu’rakhat fī Al-Mamlakah al-‘Arabiyyah al-Saudia, 2015, Riyad., pp 91 – 92 Plate 13 (b).

- R. Hoyland, “Epigraphy and the Linguistic Background to the Qur’an” in G. S. Reynolds (ed.), The Qur’an in its Historic Context, (London: Routledge, 2008) 65.

- Avraham Negev, J. Naveh and S. Shaked “Obodas The God,” Israel Exploration Journal, 36, 1/2, (1986): 56 – 60 AND J. A. Bellamy, “Arabic Verses from The First/Second Century: The Inscription Of ‘En ‘Avdat”, Journal of Semitic Studies, 35, (1990): 73 – 79.

- Fragment of kitāb al ʾAghānī: 1217 – 19. Current location: Royal Library Copenhagen, David Collection. DI/1990 (Royal Library Cod. Arab. CLXVIII).

- For the inscription see: Christian J. Robin and Iwona Gajda, ‘L’inscription de Wadi ‘Abadan’, Raydān: Journal of ancient Yemeni Antiquities and Epigraphy 6, (1994): 113 – 37.

- Robert G. Hoyland. Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam (New York: Routledge, 2001), 10.

- Fred M. Donner, The Early Islamic Conquests (Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 1981), Introduction x.

- For an example of the practical application of this principle see: Robert B. Serjeant, “Haram and Hawtah, the Sacred Enclave in Arabia,” in Melanges Taha Husain, ed. Abd al-Rahman Badawi, (Cairo: Dar al Ma’aref, 1962), 41 -58.