The prophet dies

No other single day is as significant for the religious beliefs of Muslims as the day the Prophet died. That is the day Muslims devised a number of religious canons which played a significant role later on.

The most important of them was that the Prophet was dead. There were many contemporary religions whose founders were not considered dead. When the Prophet, died his Companions argued about how to tackle the situation. Umar was of the opinion that a prophet cannot die. Abu Bakr pointed out that the death of a prophet is in line with the teachings of the Qur’an. Prophet Muhammad is actually dead. Abbas bin Abdul Muttalib confirmed that the body of the Prophet had started decaying. 1 It was ample proof for the Companions that the Prophet was dead. Since that day, it is a universal belief of Muslims that the Prophet Muhammad is dead. They might believe in the resurrection of Jesus Christ or other sacred personalities. As far as Prophet Muhammad is concerned, he is dead.

The Qur’an is complete

Another belief stemmed from the first one on the same day. With the death of the Prophet, Allah’s guidance to humans through the Qur’an stopped forever. Later Muslims might have believed that Gabriel came to Ali or Allah guided Abu Bakr through a dream, but they were sure that there were no more revelations. Many Muslims believe that Allah guides His obedient servants through dreams. Some also believe that Prophet Muhammad may guide pious people through dreams. Anyhow, these are individual guidance and have nothing to do with religious tenants. As far as basic religious tenants are concerned, they are completed on the day of the death of the Prophet.

The final shape of Qur’an

The Rashidun Caliphate attained the most important religious landmark for future Muslim generations. This was the codification of the Qur’an.

Early Islamic sources of history agree that the Qur’an was in written form during Prophet Muhammad’s time. It was scattered over many different parchments and other kinds of writing surfaces. The primary form of its preservation was memorization. So many Qur’an memorizers [ḥāfiz ul Qur’ān] died during the War of Yamama that Umar was worried about the loss of the Qur’an altogether. On his advice, Abu Bakr collected all available written material. He organized it into chapters [sūrah] and compiled them into a book form. 2, 3 Abu Bakr assembled a council of twenty-five men from the Quraysh and fifty men from the Ansar and assigned them to “write down the Qur’an and submit it to Sa’id bin al ‘Āṣ, for he is a man skilled in language”.4, 5 This exercise must have accepted only that material to be included in the Book that the assembly of Companions unanimously agreed to be authentic.

The second phase of Quran codification came during Uthman’s regime. Abu Bakr had compiled the Qur’an in book form but did not establish an official version. By Uthman’s time, according to Ya’qubi, people used to say “the Quran of the family of so and so,” and Uthman wanted the Qur’an to be one version. Uthman selected the manuscript of Abdullah bin Mas’ud, who was a government servant in Kufa at that time. “Send him to me! For this religion shall not fall into confusion, and this community shall not fall into corruption,” said Uthman sending for Abdullah bin Mas’ud. Uthman then put the long sūrahs with the long sūrahs and the short sūrahs with the short sūrahs. He made one copy of the Qur’anic text he had prepared available in all provincial capitals including Mecca, Kufa, Basra, Egypt, Syria, Bahrain, Yemen, Jazira and Medina. Uthman circulated an order across the entirety of the country to destroy the existing unofficial copies of the Qur’an. He prescribed only two methods for it: either boil it in water and vinegar or burn it. Then, he issued a decree that people should recite the Qur’an only according to the official version. 6, 7 Similar reports are given by other Islamic sources that the official version of the Qur’an was established by the order of Uthman and the sequence of surahs was agreed upon at that time. Uthman criminalized the recitation of any other version of the Qur’an except the official version.

This development of the Qur’an has been verified archaeologically. Archaeologists have discovered many folios of ancient Qur’ans from the Great Mosque of Sana’a.8 A few folios of one particular Qur’an, now called Sana’a codex I or DAM 01-27.1, discovered among them have generated a lot of interest. This Qur’an was written on parchments. Later on, the parchments were washed to re-write Qur’an on them. Ironically, the ink of the original text has reappeared to the extent that the original version can be read side by side with the later version. Radiocarbon dating of the parchment gives a 68% probability of this parchment was produced between 614 to 656 CE and a 95% probability of produced between 578 to 669 CE. This applies to earlier text written on the parchment. Later text is written either in the first or second half of the 7th century or even early 8th century CE.9 This is archaeological evidence that the Qur’an was codified during the Uthmanic era and that earlier versions were destroyed. 10 Earlier version of this manuscript, which is the only available specimen of a Qur’an before the codification of Uthmanic times, is subject to extensive research. Up to now, it has been verified that the Uthmanic text of the Qur’an and non-Uthmanic text of the Qur’an had diverged before mid of 7th century (i.e. 650 CE) and that existing pieces of revelation were joined to form the sūrahs prior to Uthman’s codification.11 These archaeological discoveries are in line with the notations of Ya’qubi.

In historical Islamic sources, Uthman’s deeds were not appreciated by anyone during his lifetime. Contrary to this, Islamic sources document criticism of Uthman on codifying the Qur’an. Anyhow, if a historian looks at these events from hindsight, this is the single most important religious achievement of the Rashidun Caliphate. The Uthmanic text of the Qur’an has been the foundation of the religious belief of all Muslims throughout the world for generations.

Despite the codification of the Qur’an by Uthman, oral transmission was the preferred mode and later on variant text proliferated again. 12 Whelan points out that Muslim tradition acknowledges the fact that readings of the Qur’an continually diverged from a supposed original. Steps had repeatedly to be taken to impose or protect a unitary text of revelation. 13 Noldeke has done a classic study on the history of the Qur’anic text as preserved in Muslim traditions.14

The current text of the Qur’an available to us, and considered authentic by the majority of Muslims, is called ‘Cairo Edition’. It was prepared at al-Azhar in the 1920s and is based upon one of the seven readings of the Qur’an permitted by Ibn Mujahid (d. 936 CE) in Baghdad. This reading was that of Abu Bakr ‘Āṣim (d. ca. 745 CE) and it was transmitted from Abu Bakr ‘Āṣim by Ḥafṣ bin Sulayman (d. 796).15

What constitutes Sunna of the Prophet?

Controversies around the bona fide Sunna of Prophet Muhammad started during the three decades of the Rashidun Caliphate. Each piece of information that transmitted something about the Sunna of the Prophet was called Hadith (Ḥadīth حَدِيث). Prophet Muhammad made sure that the revelations of the Qur’an be written for future reference. He did not, anyhow, deem it necessary that his salient Hadith be preserved in the written form before he died. The sole source of the Hadith of Prophet Muhammad became a person who had heard or seen the Prophet saying or doing something.

Some people, being the earliest Muslims, had lived with or near the Prophet for years. Others, later converting, had met him superficially. Muslims of the Rashidun Caliphate didn’t distinguish between the two categories of people as far as Hadith transmission was concerned. The only condition to qualify to be a transmitter of the Hadith of Prophet Muhammad was that the person should have seen the Prophet while being Muslim. Now, there were nearly one thousand people living in the Rashidun Caliphate who could claim that they had met the Prophet as Muslims.16 All of them had an equal right to transmit a hadith tradition.17

Initially, it was customary to produce two eyewitnesses to prove that the tradition being transmitted was genuine. In July of 638 CE, when Umar extended the boundary of the Ka’ba, he had to demolish some houses to acquire land. Abbas bin Abdul Muttalib was unwilling to let his house be demolished. He came up with a saying of the Prophet which implied that a government didn’t have a right to demolish somebody’s property. Umar aptly asked him to produce witnesses to that saying. Abbas had to produce witnesses. The witnesses could only support the saying to the extent that the government can demolish a property only after paying the reasonable price of the property assessed by the owner. Abbas had to affix a price tag and the government paid it.18

During the later years of the Rashidun Caliphate, especially during the First Arab Civil War, people transmitting the Hadith tradition insisted that the onus of it being correct is on the narrator. Meaning, the narrator was no longer bound to produce two eyewitnesses. If he produced a false Hadith statement, he would personally be responsible for the sin. 19

During and after Futuhul Buldan at least one million humans had entered into Islam. 20 A whole new generation born after the death of the Prophet had come of age. They predominantly lived in cantonment towns. None of them had met the Prophet of Islam. Their only source of Hadith was those narrators who attributed a saying or action to the Prophet without producing any eyewitness. The Companions had scattered all over the country and producing two eyewitnesses for each and every Hadith narrated was practically impossible.

The Muslim citizens of the Rashidun Caliphate used to give credit for their success in Futuhul Buldan to the blessings of Prophet Muhammad. The new generation of Muslims and the new converts to Islam were curious about the life and deeds of the Prophet. They used to sit around narrators of Hadith and listen. 21 After that the whole gathering had a right to transmit it further individually without producing any eyewitnesses. All pre-conditions were set for the production and propagation of differing versions of the same event or same saying.

In the midst of the seventh century, specifically during the fifth decade, the Muslim populace of the Rashidun Caliphate underwent a political division. Various political factions emerged, each with their own vested interests in promoting and adhering to a particular version of a tradition that aligned with their political viewpoints. It was during this period that the Sunna of the Prophet became a subject of controversy. In the Islamic historical sources of that time, we find individuals accusing others of not following the Sunna of the Prophet, while the accused individuals staunchly insisted that their actions aligned precisely with the Sunna.

There is no evidence that the Hadith were in written form during the time of the Rashidun Caliphate. The earliest hadith collectors, like Abdullah bin Mas’ud, Abdullah bin Abbas or others might have written personal notes but they didn’t distribute them to the public.

As a matter of fact, controversies around Sunna of the Prophet started so early in Islam that Umar is on the record advising his governors to confine themselves to the Qur’an and not to cite the Prophetic traditions so frequently. 22

Sayings of the prophet on political matters

We are not sure when Muslims started justifying the political actions of the rulers of the Rashidun Caliphate with the fabricated Hadith of the Prophet. But what we know for sure is that they did it sometimes down the road. Let us examine one event.

Ibn Ishaq reports that Umar expelled the Jews from Khaybar. At that time, they protested that Umar was not honouring the contract that Prophet Muhammad had himself entered into with them. Umar asked them to produce a hard copy of the contract and those who could do so got an exemption. Explaining the background of the event, Ibn Ishaq tells that Umar was fed up with their hostile activities. His patience was exhausted when they assaulted Abdullah bin Umar and dislocated his arms. Abdullah had gone to Khaybar to inspect his property there. Ibn Ishaq’s account produces two points. The decision of expelling the Jews was purely of administrative nature. And Umar was aware that this decision of his annuls the earlier administrative decision about them taken by Prophet Muhammad.23

Baladhuri reports the same event about hundred and fifty years after Ibn Ishaq. This time, the tone has changed. He attributes this tradition to Zuhri that the Prophet had said that there can be no two religions at the same time in the Arabian Peninsula. Umar investigated this saying and when he was convinced that it was authentic, he expelled the Jews of Khaybar. 24 Baladhuri’s account gives a new dimension to the event. He presents it as a purely religious decision taken by Umar in light of the Prophet’s saying. 25

Both sources of Islamic history give totally contradicting reasons for Umar’s decision. The earlier mentions administrative headaches created by the Jews as reason and the latter insists that it was Prophet’s saying. Who, out of them, is correct?

If Baladhuri is reporting exactly what transpired, one assumes that Umar should have expelled Jews from all over Hejaz. He had the power to do so. But that is not the case. According to another report of Baladhuri, Taif had a Jewish community at the time it came under the jurisdiction of Prophet Muhammad. Prophet Muhammad imposed Jizya on them.26 According to still another report of Baladhuri, Jews of Taif still lived there and paid Jizya when Mu’awiya bought a property from them. 27 This event is after Umar’s death. 28

It means Baladhri’s report that Umar expelled Jews of Khaybar only because he found out a Hadith of the Prophet is dubious, otherwise Umar would have really expelled all Jews from Hejaz.

Why did a later source quote a Prophet’s Hadith as the sole reason behind the decision of Umar? Obviously, the source was trying to justify the decision of Umar, which was otherwise contrary to the earlier decisions taken by Prophet Muhammad.

Now, if later sources had to justify successfully that whatever Umar did was to fulfill the wishes of Prophet Muhammad, they needed to document a time when the Prophet wished it. He accepted the presence of Jews in Taif just two and a half years before his death. He didn’t send any eviction notice to the Jews of Khaybar until his death. The only time they could allot for this Hadith of the Prophet was at his deathbed. This is what they exactly did. In Ibn Ishaq’s Sirah, the Prophet says so on his deathbed. As this quotation is totally out of context there and as Ibn Ishaq doesn’t emphasize that it was the sole reason for the decision of Umar, it is obvious a later copier has injected this sentence into Ibn Ishaq’s sirah.

There are a lot of Hadiths attributed to Prophet Muhammad that have purely political, and not religious, content. If we screen the whole of Sirah and Hadith literature, none of them is about any event that falls chronologically after the attack on Constantinople in international politics and the Battle of Siffin in internal politics.

Worships

All kinds of worship (‘ibādah عِبادَه) from Prophetic times continued during Rashidun Caliphate. Dying in the war was such an achievement in the eyes of Muslims that the Rashidun Caliphate didn’t consider giving much remuneration to a dead soldier. The martyrs of Qadisiyyah were paid only a token of money.29

Two ritual prayers (ṣalāt) became very popular during the years of the Rashidun Caliphate. One was Tarawih (Tarāwīḥ تَراويح) and the other was Jum’ah (Jum’ah جُمَعَه).

A ritual prayer after supper in Ramadan (Ramāḍān رَمَضان the month of fasting) might have been practiced during the Prophetic times. 30 Umar officially established it as the Sunnah of the Prophet in 635 CE. He wrote to the people of cantonments that they should pray qiyām shahr Ramāḍān in the mosques. He also asked the authorities to ensure compliance with it.31 Probably Umar formalized them by having them prayed behind a single reader in the mosque, rather than as purely individual devotions.

Congregational prayer on a Friday (Jum’ah) can be traced back to the time of Ansar’s acceptance of Islam in Medina before the Prophet’s immigration there. Its attendance never became compulsory (farḍ فَرض). The Prophet used to talk to the people on this occasion but the nature of these talks is not known. Probably they were purely religious sermons. During the time of the Rashidun Caliphate, it changed in a few ways. Political news used to pour in frequently. The caliph, or his designated governor, used to keep people abreast of the latest developments. The sermon (Khuṭbah خُطبَه) of Friday prayers became a kind of weekly press conference. It contained both pressing religious affairs and current affairs. Attending the Friday congregation became a kind of social pressure. If you didn’t attend it regularly, it meant you were cutting yourself off from the community or you are disloyal to the government. 32, 33

Uthman further formalized the occasion when he introduced a special prayer call (azān اذان) for this occasion. Muslims had constructed grand mosques in each and every town or village they resided in. They expected attendance of Friday congregation in that mosque. 34 Muslims were free to offer other prayers in their local mosques. Once rooted deeply in the Muslim community, the Friday congregation became the site of all kinds of political juggling.

Praying for rain was a pre-Islamic tradition. We hear of Meccans praying for rain at Mount Qabus. Probably, the need never arose during the Prophetic time. During the 639 CE drought of Medina, Umar took the entire community of Medina outside the town to pray for rain (istisqā’ اِستَسقاء). He held the hand of Abbas during the prayer.35 Ya’qubi reports that the rain did come after prayer.36

Compulsory ritual prayer (ṣalāt) maintained its supremacy over other kinds of worship. People could miss others but they never thought of missing compulsory ritual prayer. Umar was fatally wounded in the mosque before he could lead the prayer. People completed the prayer before giving him any kind of first aid. 37 Participants of the Battle of Jalula performed their noon prayer by just nodding their heads. 38 Participants of the Battle of Yamama had done the same thing, though, on occasions, they delayed the ritual prayer and offered it later. 39 Tabari mentions a woman by the name of Qaṭami practicing withdrawal (Mu’takifah مُعتَكِفَه) during the Ramadan in 661 CE in Kufa in the great mosque.40

Believe in true dreams

Like in Pre-Islamic Arabia, Muslims of the Rashidun Caliphate continued to believe in true dreams. Common men kept claiming that they dreamt of true future events. 41

Side business around Hajj changed

During pre-Islamic times Arabs attended many kinds of side businesses when they came to Mecca for pilgrimage. Trade deals, arbitration on disputes, poetry competitions, and news exchange are a few of them. We don’t hear about them during the Rashidun Caliphate. They might have continued but would have decreased in significance. The main economic activity of the country shifted northwards. Highway safety might have stimulated the growth of year-round markets in towns all over Arabia. People had less incentive to postpone their shopping spree for the time of Hajj.

A new side business started during the Hajj season [mousim]. Caliph Umar ordered all governors of provinces, lieutenant governors and other high-ranking officers to come for pilgrimage every year. All of them assembled at a conference on this occasion to give their performance report to the caliph. Afterwards, Umar used to hold an open court in the presence of governors. Umar acted as an ombudsman and common people from provinces could complain against their respective governors. 42 Probably open court got defunct during Uthman’s tenure but the governor’s conference continued. That was the last governor’s conference of the Rashidun Caliphate which remained indecisive on the issue of tackling the rebels.43

Political aspirants started using the occasion of Hajj to lobby for themselves from Umar’s time onward. Later on, when the Rashidun Caliphate imposed a travel ban due to fear of political dissent, pilgrimage became a valid excuse to travel and organize dissent.

A leader for Hajj

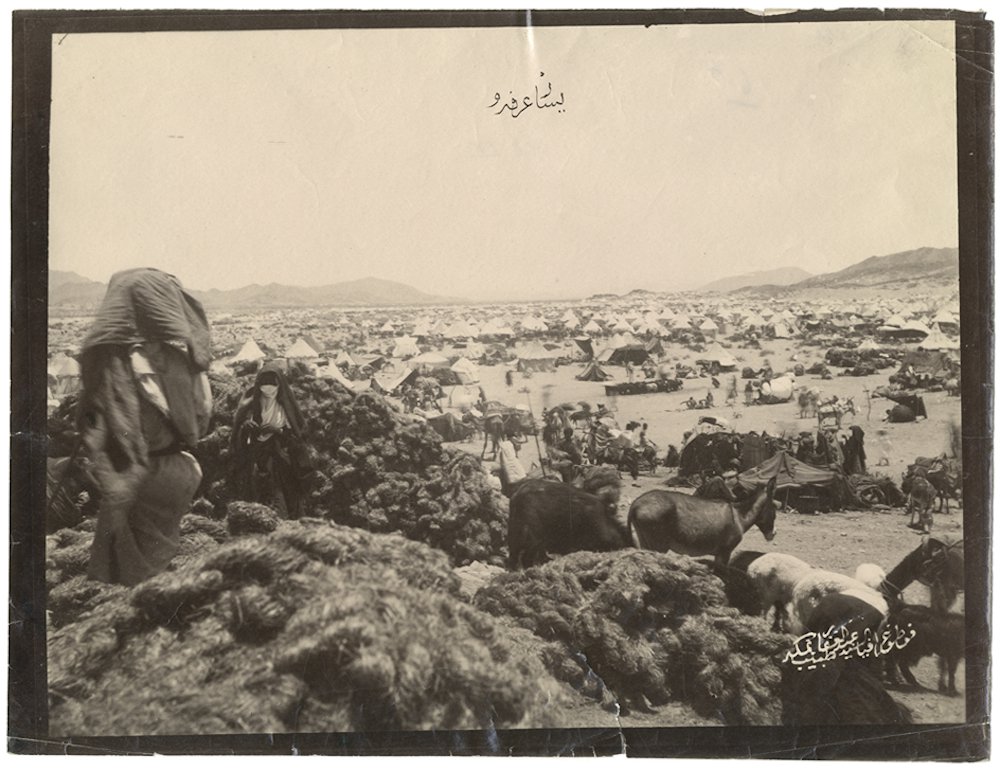

Camping at Arafat. 44

Ali never led the Hajj, neither before becoming a caliph nor after becoming a caliph. Ali’s nonattendance of Hajj after becoming caliph highlights the deterioration of governmental organization. During the first two years of Ali’s caliphate, Abdullah bin Abbas led the Hajj. In the third year, it was his brother, Ubaydullah bin Abbas, who had a chance to lead the pilgrims. The Hajj of Ali’s last year was disorganized when Ali could not appoint anybody to lead the Hajj. Syayba bin ‘Uthmān, whose family was appointed by the Prophet as caretaker of the Ka’ba, stepped forward to fill the gap of the leader. 48 Most ridiculous event of this year’s Hajj was that Mughira bin Shu’ba appeared in front of people and claimed that he was appointed leader of Hajj by Mu’awiya.49

The role of the leader of Hajj was to be present throughout the Hajj season, lead the people in prayer and stand at Arafat (‘Arafāt عَرفات) on the Day of Moistening and Slaughtering [8th Zul Hijjah]. 50

Expansion of Hajj volume

As the wealth of Muslims grew, their numbers increased, highways became safer, and the number of pilgrims (ḥujjāj حُجَّاج) increased exponentially. Shortly after Umar took office as caliph, the crowd at the Ka’ba during Hajj season became unmanageable. He had to expand the premises of Ka’ba in July of 638 CE. 51 In doing so, he pioneered another precedent in Islam. The construction and expansion of the Ka’ba became the responsibility of the central ruler of the land. Previously, the local authorities of Mecca were responsible for the building of Ka’ba. Umar took Muqām Ibrāhīm further away from the Beyt. He expanded the Ḥijr (Ḥaṭīm). Umar undertook the expansion of the Ka’ba compound, which involved the demolition of certain houses. Additionally, he introduced a novel architectural feature to the Sacred Mosque (Masjid al-Haram) that had not existed previously. Umar constructed a boundary wall around the compound, reaching the height of an average person, and adorned it with lamps on top. Moreover, he enhanced the aesthetics of the Ka’ba, adding further decorative elements to it. In pre-Islamic times, the cover of the Ka’ba was made up of pieces of leather and ma’āfir cloth. The Prophet had changed it with Yamani cloth. Umar covered it with Coptic cloth. 52 Umar also built two dams in Mecca to protect the Ka’ba from floods.53 In the next few years, the premises of the Ka’ba again became congested. Uthman had to expand it further in 647 CE. In doing so, he again claimed the government’s right of way on certain properties and bought them to demolish them. Public protests broke up in Mecca against the government policy of acquiring land against people’s will. Uthman curbed them by arresting and jailing the protestors. Uthman made modest changes in the design. He raised porches on the boundary wall. 54

As the volume of pilgrims to the Ka’ba increased, so increased the traffic on the roads leading from the cantonments to Mecca. An inscription scribed by certain ‘Abd al Raḥmān bin Khālid bin al ‘Āṣ in 660 CE in Wādī ‘l-Shamiya en route Darb Zubayda confirms that this famous Hajj route was operative in the last years of Rashidun Caliphate.55

The role of the Prophet’s Mosque

In addition to being a central place of worship for Medina, the Prophet’s Mosque continued to function as a central secretariat for the Rashidun Caliphate up to the time Ali abandoned Medina. Then this role shifted to Qasr al Amarah (governor house) of Kufa, never to return to Medina. Islamic sources don’t note any touristy hustle and bustle in the mosque or the adjacent Ḥujrah where Prophet Muhammad laid buried.56 The mosque of the Prophet retained its religious significance, in any case. The rulers of the Rashidun Caliphate were never thrifty in spending money on renovation, expansion and beautifying the mosque.

The first enlargement of the Prophet’s Mosque came in the time of Umar. Umar asked Abbas bin Abdul Muttalib to sell his house to the mosque for an extension, but he rather donated it. The boundary wall ended up having six doors.57 Uthman totally reconstructed the mosque in November 649 CE. He made the structure of stone and gypsum, supported the teak wood roof with stone columns inlaid with lead, and covered the walls with an outlay of small pebbles brought from Al-‘Aqīq. The newly constructed mosque was fifty cubits wide and sixty cubits long.58

Site of the mosque not sacred

In an interesting tradition, Tabari reports that Umar ordered the removal of the grand mosque of Kufa from its original place to another one. 59 According to Tabari, the original grand mosque of Kufa had a roof supported by pillars without any surrounding walls. The boundary of the mosque was marked by a ditch. The ceiling design was copied from a Byzantine Church. The material used in the ceiling was probably from the palaces of Sasanian Iran.60

May Allah be pleased with him

Muslims developed special reverence for the Companions of Prophet Muhammad during the first three decades of Islam. Umar’s insistence to treat a Companion of the Prophet preferentially in government jobs might have played a part. Umar’s official hierarchy in Islam might have further strengthened it. Not only this, they had the exclusive privilege of transmitting Hadith, at least in the beginning. Others had to hold their opinion on religious matters if a Companion was present at the gathering.

Initially, the reverence for all earliest Companions of the Prophet was equal until the advent of Abdullah bin Saba’. Under the influence of his teachings, Muslims started comparing the merits of early Companions and making a hierarchy of Companions in their minds.

Archaeological evidence suggests that Muslims did not necessarily follow the name of any Companion of the Prophet with the saying, ‘may Allah be pleased with him’ (razī Allah ‘anhā), until the death of Uthman. 61, 62 We find this phenomenon during First Arab Civil War for the first time. Whenever Shi’a Uthman mentioned his name in their conversations, they paused and stressed ‘may Allah be pleased with him’ before expressing anything further. 63 This might be in the backdrop of the cold-blooded murder of Uthman. His murderers claimed that he had deviated from the correct path of Islam. Later on, the same wording might have been extended to all dead Companions of the Prophet. To make it universal it may have changed to ‘May Allah be pleased with them’. (razī Allah ‘anhum).

First religious scholars

No organized religion can flourish unless it has a body of people who have a passionate interest in its promotion. They are the people who scrutinize religious practices in their society and object to variation from set standards. Of course, they earn their livelihood through their religious activism.

Prophet Muhammad himself inaugurated the institution of ‘religious scholar’ (sin ‘Ālim; pl. ‘Ulamā’). After Fath Mecca, he appointed Abu Musa Ash’ari to teach the Meccans Islam. His appointment was entirely separate from Attab bin Asid, who was responsible for the administrative affairs of Mecca. The practice continued. When Umar appointed Mu’awiya governor of Syria, at the same time he appointed two Companions of the Prophet, Abu ‘l Dardā’ to act as a qadi (qāḍi قاضى) and to conduct prayer at Damascus and Jordan and ‘Ubādah to act as a qadi and conduct prayer at Homs and Qinnasrin. 64

The religious scholars were of various categories depending upon their job. The scholars mentioned in the above example served as leaders of religious rituals. They were later called imam (imām اِمام) of a mosque in mainstream Muslim tradition. There was another class of religious scholars. Ya’qubi mentions that Abu Bakr used to get religious consultations from Ali bin Abu Talib, Umar bin Khattab, Mu’adh bin Jabl, Ubayy bin Ka’b, Zayd bin Thabit and Abdullah bin Mas’ud.65 They had a right to interpret the Quran and the Sunnah of the Prophet. They were called Fuqaha (fuqahā’ فًقَهاء pl. Faqīh فَقِيه sin.). All Fuqaha during Umar’s reign were Companions of the Prophet. They were Ali, Abdullah bin Mas’ud, Ubayy bin Ka’b, Mu’adh bin Jabl, Zayd bin Thabit, Abu Musa Ash’ari, Abu ‘l Darda, Abu Sa’īd al Khudri, and Abdullah bin Abbas.66

All Fuqaha who served Umar continued to serve Uthman, however, there were two notable changes. Ali dropped out of the list and two new faces entered into the list. One was Abdullah bin Umar, son of the late caliph and a Companion himself. The other was Salmān bin Rabī’ah of the Bahila tribe. 67 The entrance of Salman into the list of fuqaha during Uthman’s reign is astonishing. He was the first faqih who did not have a background in early Islam in Mecca or Medina. Otherwise, he is credited to be a Companion of the Prophet. 68 He died in the battle of Balanjar. By the time Ali became caliph, he was a faqih on his own merit. He did not consult anybody else on religious matters. However, there were religious scholars of renown during his time who are said to have obtained their knowledge from Ali and transmitted it to others. Ali’s companions who transmitted knowledge from him were: Ḥārith al A’war, ‘Āmir bin Wāthila, Ḥabba bin Juwayn, Rushayd al Hajari, Ḥuwayza bin Mushir, Aṣbagh bin Nubāta, Mītham al Tammār, and Ḥasan bin ‘Ali. 69, 70

All religious scholars mentioned up to now were somehow attached to the government. They were directly or indirectly paid by the government for their services. During the later phase of the Rashidun Caliphate, a new genre of religious scholars appeared. They had come from the rank and file of common people. They had gained knowledge of the Qur’an and Hadith and people believed in their interpretations. They were paid by common people for their religious activism. A vivid example is Abdullah bin Saba’.

Caliph final religious authority

Despite the existence of religious scholars in society, the caliph was the final religious authority. Whenever a difference of opinion arose on religious matters, the caliph’s opinion was final and binding. He could consult fuqaha but the final words came from his mouth. People doubted that Sa’d bin Waqqas prayed in a prescribed way. Umar heard the way how Sa’d prayed and decided on his own that he prayed the way it was prescribed by Prophet Muhammad. Nobody challenged Umar’s authority here. Actually, Umar used his authority to codify a new religious law in the case of Abu Jandal versus the state. 71 He also used the same authority when he banned Umrah during the month of Zil Hijjah so gathering at the time of Hajj shouldn’t diminish. 72

The scene continues during Uthman’s tenure, though initial dents to the unchallenged position of caliph on religious matters can be seen. Uthman offered four bowings (rak’atayn) instead of two at Arafat in August of 650 CE during the Hajj, contradicting the previously existing precedent of the Prophet, Abu Bakr and Umar. He insisted that his privilege of being caliph of the Muslims allowed him to modify the religion. People challenged him. After a big hue and cry, ultimately, Uthman’s position won and the earliest Companions including Ali and Abdur Rahman bin Awf had to give way. 73, 74, 75

When Ali came to power, the caliph’s monopoly on religious matters was a memoir of the past. Constitutionally caliph remained the supreme religious authority. However, all Muslim citizens of the Rashidun Caliphate never recognized Ali as a caliph. In other words, they didn’t vest any religious authority in Ali. And those who vested religious authority in Ali didn’t honour their own decision whenever they had religious differences with Ali.

A changeable religion

Flexibility and adaptability are prerequisites for any religious system if it has to be popular over multiple cultures and succeeding generations. The earliest Muslims were aware that as time passes, the religion will need new interpretations. They called this process Ijtihad (ijtihad اِجتِهاد). Ijtihad took effect from the day the Prophet died. The prominent Companions of the Prophet unanimously decided, after exhaustive discussion, that the Prophet was dead. 76 The right to Ijtihad no longer remained an oligopoly of Companions of the Prophet during the lifetime of the Rashidun Caliphate. It spilled over to anybody who could convince the masses that he was well-versed in the religion. Neither Abdullah bin Saba’, nor Mītham al Tammār were Companions of the Prophet.

First sects in Islam

No major religion in the world is without sects. Whenever a religion grows to a certain extent it starts dividing into religious sects. Political discords during the latter half of the Rashidun Caliphate resulted in the first religious sect that clearly distanced itself from the mainstream Muslims. The Kharijis believed in the absolute supremacy of the Qur’an over the Sunna of the Prophet. Mainstream Muslims believed in the superiority of the Qur’an over Sunna, but they saw Qur’an and Sunna in conjunction with each other. They didn’t see any contradictions between the two. Shi’a Islam was still a political viewpoint at this time.

Different shades of Islam

During the Rashidun Caliphate, not only did various prototypes of later sects emerge, but there were also Muslim individuals whose lifestyles and personal practices did not align with the majority. As the number of people embracing Islam grew, it became inevitable that differences of opinion would arise on religious matters. In 654 CE, there was a man named ‘Āmir bin ‘Abd Qays who lived in seclusion near Basrah. He chose not to marry, abstained from eating meat, and did not attend the Friday prayer. Instead, he immersed himself in reading the Qur’an (muṣḥaf) for most of his time. Abdullah bin Amir, the governor of Basrah, expressed his desire to meet ‘Āmir and sent a message through one of his attendants, Ḥumrān bin Abān. However, ‘Āmir remained engrossed in his reading, paying no heed to the governor’s request.

Humrān, feeling frustrated, reported to the governor that ‘Āmir considered himself equal to even the esteemed lineage of Abraham. Intrigued, the governor personally visited ‘Āmir. ‘Āmir closed the Qur’an and engaged in a one-hour conversation with the governor. The governor extended an invitation for ‘Āmir to visit his official residence, intending to honour him. ‘Āmir declined, stating that such honours were bestowed upon Sa’īd bin Abi ‘Arjā. The governor then offered ‘Āmir a government position, to which he responded that Ḥuṣayn bin Abi Ḥurr was interested in such roles. Subsequently, the governor proposed arranging a marriage for ‘Āmir, but he stated that Rabi’ah bin ‘Isl found women appealing.

Finally, the governor confronted ‘Āmir about his views on the superiority of Abraham’s lineage. In response, ‘Āmir opened the Qur’an and pointed to the verse: “Allah chose Adam and Noah and the family of Abraham and the family of ‘Imran over the worlds.” [Qur’an 3:30]. While Humrān was in Medina, he spoke negatively about ‘Āmir bin ‘Abd Qays, and many people testified against him. Uthman then exiled him to Syria. Mu’awiya interviewed ‘Āmir and offered him a portion of bread prepared with broth and meat, which ‘Āmir consumed.

Regarding the Friday prayer, ‘Āmir mentioned that he attended it but stayed at the back and left early. He explained that he abstained from eating meat slaughtered by butchers after witnessing one dragging a sheep, repeatedly chanting “for sale” until it dropped dead. However, he ate meat when Mu’awiya offered it to him. ‘Āmir informed Mu’awiya that he remained unmarried because he had not found a suitable bride, although he was engaged at the time. Mu’awiya permitted him to return, but ‘Āmir refused, citing the ill treatment he had received from the people in Basrah. Consequently, he chose to stay in Syria.

Mu’awiya used to ask him frequently about what he needed, to which ‘Āmir always responded, “Nothing.” On one occasion, ‘Āmir remarked, “If you give me back some of Basrah’s heat, perhaps fasting would be something difficult for me, for in your country it is easy.” 77 In this account, we encounter a man who held his own unique religious beliefs that diverged from the mainstream. It is possible that his perspectives underwent some revision following his meeting with the considerate Mu’awiya. As a result, he had no desire to return to his previous life, viewing his exile as a blessing.

Muslim kafirs

The decades of the Rashidun Caliphate produced, for the first time in the history of Islam, what we can call Muslim Kafirs (Kāfir كافِر). Kafir was a word reserved for Arab polytheists who opposed Islam fiercely in its early phase. By the time the political stability of the Rashidun Caliphate crumbled, Muslims started labelling their own fellows kafir.

The Kharijis stated openly that both Ali and Mu’awiya were kafirs. 78 The use of world kafir in this sense started earlier than Ali’s caliphate.

Islamic sources don’t use the word kafir explicitly for Uthman but telltale traditions survive. The rebels against Uthman in Fustat enumerated all vices of Uthman in a public gathering. In the end, the public gathering concluded that the blood of Uthman was licit, meaning they declared Uthman an apostate. 79, 80

Blaming a Muslim to be a kafir has clear political connotations. During First Arab Civil War it provided a moral framework to physically eliminate political opponents. It continued in the same way during later times.

Blaming a Muslim kafir was a clear deviation from the Sunnah of Prophet Muhammad. He had never blamed a Muslim kafir come what may.81 Islam was inclusive during the Prophetic times as it needed adherents. Now it became exclusive as adherents were plenty.

Eating taboos

During the Rashidun Caliphate, Muslims adhered to certain dietary restrictions and taboos regarding the consumption of specific types of meat. A common condition included in treaties was to provide accommodation and hospitality to a needy Muslim for a night. In one such treaty documented by Habib bin Maslama, it was specified that the Muslim guest would be served food permissible by the “People of the Book,” indicating that it would be acceptable for Muslims to partake in it. 82 We are not sure how strictly they followed it. In one tradition preserved by Tabari, a dehqan of newly defeated Iranians brought food for field commander Abu ‘Ubayd and his companions and they ate it. It included meat.83

No aversion to the statues

Within the Great Hall of the White Palace in Tswyn, numerous plaster statues depicting men and horses were present and left undisturbed by Sa’d bin Waqqas during his stay in the palace. Sa’d, in gratitude for his victory, performed eight rak’as ritual salat as an act of thanksgiving. Interestingly, he transformed the hall into a place for subsequent ritual prayers without removing or covering the statues. 84

General religiosity

After studying the themes in Arabic graffiti written in inscriptions during the first Islamic century, Hoyland points out that there was a particular religiosity prevalent among Arabs. This phenomenon was prominent during the caliphates of Abdul Malik and Walid, according to Hoyland. 85 New discoveries of dated inscription push back this phenomenon to the late year of the Rashidun Caliphate. In an inscription discovered in Wādī Khushayba, near Najran in modern Saudi Arabia, a certain Yazīd bin ‘Abdallah al Salūlī asks for the forgiveness of Allah (and nothing else). Yazid didn’t forget to write the year. It was 650 CE. 86

Muslims in the eyes of others

After its advent in the Arabian Peninsula, Islam came in contact with people of other faiths and ethnicities in Sasanian Iran and Byzantine Rome during the Rashidun Caliphate. A few glimpses have survived of how they perceived the Muslims’ faith.

John of Fenek, the seventh-century monk, states “Arabs kept to the tradition of Muhammad, their instructor, to such an extent that they inflicted the death penalty on anyone who was seen to act brazenly against his laws.” 87

Sebeos notes, “In that period a certain one of them, a man of the sons of Ishmael named Muhammad, a merchant, became prominent. A sermon about the Way of Truth, supposedly at God’s command, was revealed to them, and [Muhammad] taught them to recognize the God of Abraham, especially since he was informed and knowledgeable about Mosaic history. Because the command had come from One High, he ordered them all to assemble together and to unite in faith. Abandoning the reverence of vain things, they turned toward the living God, who had appeared to their father, Abraham. Muhammad legislated that they were not to eat carrion, not to drink wine, not to speak falsehoods, and not to commit adultery.” 88 Few points are recognizable in Sebeos’ text. He knew that God revealed a sermon to Prophet Muhammad. He was also aware that Prophet Muhammad was well-versed in Mosaic traditions. He understands that Pre-Islamic Arabs believed in Abraham and his God. Prophet Muhammad invited them to abandon their reverence in vain things [idols] and turn to the living God of Abraham. Sebeos acknowledges that Prophet Muhammad united Arab tribes in one faith. Sebeos further knows that Muslims avoided eating carrion, drinking alcohol, telling a lie and committing adultery, and all these things are legislated to them by Prophet Muhammad.

The importance of Abraham to Muslims is noted in the mid-seventh-century chronicle of Khuzistan. Some modern scholars point out that the Christians of late antiquity do not mention Islam as a new religion. We know that the late antique Christians believed that their faith “took its beginning from Abraham, the first of the fathers” 89 The late antique Christians also had a deep-rooted belief in there being only one true religion, all else being heresy and error. 90 When late antique Christians mention ‘Arab’s’ religious views on Abraham or Muhammad, as mentioned in the two examples above, they are definitely excluding the Arabs from the Christians and are indirectly admitting that a new religion is on the horizon. Hoyland believes that the notion that Islam was not a separate religion in the seventh century is a whim of certain modern scholars.91

Notes on religious beliefs of Zoroastrians

After Futuhul Buldan Muslims started living side by side with Jews, Christians, Zoroastrians and Buddhists. Out of them, Zoroastrians’ religious beliefs before the conquest of Iran by Muslims are relatively less known. Here are a few comments about the organization of their religion. Apparently, Zoroastrians did not have any central authoritative pontiff over them. Regional priesthood enjoyed a large measure of independence. Each and every Zoroastrian had to follow a dastwar/dastūr who guided him or her. The dastwar could delegate his authority to a priest under him, but he himself had to recognize the authority of a superior dastwar. Various dastawr differed from each other and choosing the right dastawr was of utmost importance. As various dastawr traditions were oral, it was impossible for the highest authorities to control the teachings of local or regional dastawr, unless it posed a serious threat to the faith. This situation gave tremendous authority to the local dastawrs.92Kreyenbroek, Philip G., ‘Spiritual Authority in Zoroastrianism’, Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 17, (1994), 1 – 16

End notes

- The Expeditions: An Early Biography of Muḥammad, Trans. Sean W. Anthony. (New York: New York University Press, 2015) 113.

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 759.

- Actually, according to Ya’qubi, Abu Bakr was reluctant in the beginning as the Prophet had not compiled the Qur’an in book form himself. Umar kept pushing. See: Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 759.

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 759.

- Ya’qubi tells that Ali had collected the Qur’an after the death of the Prophet. He brought it loaded on a camel and said, “This is the Qur’an I have gathered.” Ya’qubi doesn’t give further details about what happened to Ali’s manuscript of the Qur’an. See: Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 759.

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 811.

- Ya’qubi asserts that Uthman had made sure that no copy of other versions survived. See: Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 811. Ya’qubi further reports that Abdullah bin Mas’ud developed differences with Uthman during the process of codification. The differences appear to stem from the way Uthman ordered Abdullah bin Mas’ud to hand over his manuscript to Abdullah bin Amir, the governor of Kufa. Abdallah bin Amir was young in age and very junior in the hierarchy of Islam. Abdullah bin Mas’ud refused to comply with the order flatly. Then Uthman harshly summoned Abdullah bin Mas’ud to Medina and on his arrival in Medina insulted him. Abdullah bin Mas’ud also didn’t agree with burning all existing copies of the Qur’an. Though Uthman apologized later on for his behaviour and even offered compensation, Abdullah bin Mas’ud never forgave Uthman. He did not return to his government job and took retirement in Medina where he died in 653 CE. See: Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 811, 812.

- U. Dreibholz, “Treatment of Early Islamic Manuscript Fragments On Parchment: A Case History: The Find At Sana’a, Yemen”, in Y. Ibish (Ed), the conservation and preservation of Islamic manuscripts, proceedings of the third conference of al-Furqan Islamic Heritage foundation 18 – 19 November 1995, 1996, Al-Furqan Islamic Heritage Publication: o. 19: London (UK), p. 131 & p. 140.

- Behnam Sadeghi and U. Bergmann, ‘The Codex of a companion of the prophet and the Quran of the prophet”. Arabica 57 (4) (2010) 348 – 354.

- Behnam Sadeghi and U. Bergmann, ‘The Codex of a companion of the prophet and the Quran of the prophet”. Arabica 57 (4) (2010) 348 – 354.

- Sadeghi & M Goudarzi, “Ṣan’a I And the Origins of the Qur’an”, Der Islam 87, issue 1 – 2 (2012) 1 – 129.

- Estelle Whelan, “Forgotten Witness: Evidence For the Codification Of the Qur’an”, Journal of the American Oriental Society, 1998, Volume 118, pp 1 – 14.

- Estelle Whelan, “Forgotten Witness: Evidence For the Codification Of the Qur’an”, Journal of the American Oriental Society, 1998, Volume 118, pp 1 – 14.

- T. Noldeke, Geschischte des Qorans, 2nd ed., F. Schwally, vol. 2 (Leipzig, 1919). A summary of the history of the Qur’anic text can be seen in: W. M. Watt, Bell’s Introduction to the Qur’an (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1970.

- Estelle Whelan, “Forgotten Witness: Evidence For the Codification Of the Qur’an”, Journal of the American Oriental Society, 1998, Volume 118, pp 1 – 14.)

- According to Tabari one thousand Companions of the Prophet participated in the Battle of Yarmouk. See: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XI, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Khalid Yahya Blankinship (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1993), 94. This is the maximum number of Companions reported on one occasion. The actual number of Companions could be a little higher.

- Tabari includes in the list of Companions people like Tulayha bin Khuwaylid, and Qays bin Makshuh. See: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Gautier H. A. Juynboll (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 180.

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018),778.

- Abu Musa, speaking in Kufa just before the Battle of Camel asked people to avoid taking part in the confrontation. He produced a Hadith to support his viewpoint, ‘You’re better off sitting than you will be standing in it’. He said we, the Companions of the Prophet are better able to solve the problem. Ammar bin Yasir, who was instigating people on Ali’s behalf to fight against ‘Meccan Alliance’, asked him if he had really heard this from the Prophet. Abu Musa said here is my hand to prove what I say. [Meaning you can punish me the same way you punish a thief if I am lying]. Ammar was still not satisfied and asked Abu Musa if and when the Messenger of Allah said something to him specifically. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVI, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Adrian Brockett (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1997), 94, 95.). Abu Musa did not provide the time and the situation.

- See above for the figure.

- Look at an example of such gatherings: Ḥubbah bin Juwayn al ‘Urani were visiting Ḥudhayfah [Ḥudhayfah bin Yamān of ‘Abs tribe was Ali’s governor over Tyswn, a Companion of Prophet] at Tyswn. They asked Ḥudhayfah to narrate a Hadith because they were afraid of the time of fitan. He replied, “Hold to the party in which is Ibn Sumayyah [‘Ammar bin Yasir], for I heard the Prophet saying, ‘The party of oppression that swerves from the [right] road will kill him, and his last sustenance will be milk mixed with water.’” See: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 65. Take note of the purely political content of Hadith.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. Rex Smith (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994), 108.

- Muhammad Ibn Ishaq, The Life of Muhammad. Ed. and Trans. Alfred Guillaume, (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2013), 523 – 525.

- Al-Imām abu-l ‘Abbās Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 48.

- Ibn Ishaq does mention this Hadith of the Prophet being investigated by Umar at the time of the Jews’ expulsion, but he mentions the hostile activities of Jews towards Muslims of Medina in-depth and links them with Umar’s decision to expel the Jews. Baladhuri doesn’t mention a single hostility on the part of the Jews and attributes Umar’s decision purely to the Hadith. The tone of the two sources is opposite to each other.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 86.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 86.

- Ya’qubi withholds both points of view. He says Umar expelled the Jews of Khaybar from the Hejaz when Muẓahhir bin Rāfi’ al Ḥārithi was killed. At that time Umar said “I heard the Messenger of God say, “Two religions shall not coexist in the peninsular of Arabs.” So he divided Khaybar into sixteen shares. See: Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 787. However, Ya’qubi also fails to explain why Umar was partial in fulfilling Prophet’s wish and he did not expel Jews from other parts of Hejaz.

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 772.

- Matthew points out that the practice of tarāwīḥ can be traced back to the Prophetic times. See: Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 766, footnote 931.

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 766.

- For an example of social pressure for the Jum’ah congregation see: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. R. Stephen Humphreys (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 127, 128.

- Sa’d established regulations concerning the performance of ritual prayer after the conquest of Tyswn. He ordered to offer Friday prayer in the hall of the White Palace. It was with the background that Muslims should show up for the two festivals and the pray in open but Sa’d ordered it in the hall. See: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Gautier H. A. Juynboll (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 30, 31.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. R. Stephen Humphreys (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 127, 128 AND Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Gautier H. A. Juynboll (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 31.

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018),779.

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018),779. See also: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Gautier H. A. Juynboll (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 156, 157.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. Rex Smith (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994), 91.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Gautier H. A. Juynboll (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 41.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XI, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Khalid Yahya Blankinship (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1993), 97.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 215.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVI, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Adrian Brockett (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1997), 99, 100.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. Rex Smith (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994), 34.

- See above.

- Photo credit Syed Abdul Ghaffar/Hurgronje. C. 1885 CE.

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 764.

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 793.

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 820.

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 881.

- Khalifa alleges that Mughira presented a forged document according to which he was appointed the leader of Hajj by Hasan bin Ali. See: Khalifa Ibn Khayyat, Khalifa ibn Khayyat’s History on the Umayyad Dynasty (660 – 750), ed. and trans. Carl Wurtzel, (Liverpool, Liverpool University Press, 2015), P 53, Year 41.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Michael G. Morony (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1987),6 AND Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 202.

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018),778.

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018),778. AND Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 73, 74, 76. AND ‘Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Gautier H. A. Juynboll (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 159.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 82.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 73, 74. AND Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 800.

- A. H. Sharafaddin, “Some Islamic Inscriptions Discovered on the Darb Zubayda,” Atlal (The Journal of Saudi Arabian Archaeology), 1 (1977): P 69 – 70, Plate 49.

- The Prophet had warned against grave worship. The Expeditions: An Early Biography of Muḥammad, Trans. Sean W. Anthony. (New York: New York University Press, 2015) 111.

- Al-Imām abu-l ‘Abbās Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 20, 21). AND Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 803.

- Al-Imām abu-l ‘Abbās Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 20, 21. AND Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018),803 AND Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. R. Stephen Humphreys (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 38.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Gautier H. A. Juynboll (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 72.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Gautier H. A. Juynboll (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 69.

- See inscriptions mentioning Umar and Uthman above.

- For the wording of the formula see: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 66.

- For example see: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 15.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 217.

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018),764.

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 795.

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 821.

- See: Ibn Khallikān, Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad, Ibn Khallikan’s Biographical Dictionary, Trans. B Mac Guckin De Slane, (Paris: Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland, 1853), P 447, vol. 4.

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 881, 882.

- Ḥārith al A’war bin ‘Abdallah bin Ka’b of the Hamdan tribe was a learned Kufan who died in Kufa in the days of Ibn Zubayr; Abu ‘l Ṭufayl ‘Āmir bin Wāthila of Layth tribe is said to be a Companion of the Prophet who was an associate of Ali. He later supported the revolt of Mukhtar; Ḥabba al ‘Urani bin Juwayn al Bajali was a Kufan who died in c 695 CE.; Rushayd al Hajari al Farisi was a client of Ansar. He was a strong supporter of Ali and was killed by Ubaydullah bin Ziyad; Ḥuwayza bin Mushir is an unidentified personality; Aṣbagh bin Nubāta al Mujāshi’ of the Tamim tribe served as Ali’s head of police; Mītham al Tammār was a slave whom Ali bought and manumitted. He became a strong partisan of Ali and was imprisoned by Ziyad together with Mukhtar. He was crucified in Mecca by Ubaydullah bin Ziyad after Mu’awiya’s death.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Gautier H. A. Juynboll (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 151, 152.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. Rex Smith (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994), 140.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. R. Stephen Humphreys (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 38, 39, 40.

- At this juncture of the history of Islam, Abdullah bin Mas’ud reconciled the earliest Companions by arguing that differences on trivial matters produce nothing but division. See: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. R. Stephen Humphreys (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 38, 39, 40.

- For Arabic word of rak’atayn see: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XI, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Khalid Yahya Blankinship (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1993), 97.

- See above.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. R. Stephen Humphreys (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 127, 128.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 100.

- For the details of the public gathering see: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. R. Stephen Humphreys (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 77.

- After Uthman’s death, when his family and friends wished to bury him, the Ansar of Medina didn’t allow them to bury him in Baqī’ on the grounds that he did not qualify to be buried in the ‘Muslim’s graveyard’. The very reason that Uthman kept reciting Qur’an during his siege doesn’t appear to be from a fear of death or depression. He simply insisted that he was a Muslim. Other instances of the use of the word kafir by the Muslims before the caliphate of Ali are there. While writing to Mu’awiya, Uthman says that ‘Medinites have become unbelievers [kafir]’. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. R. Stephen Humphreys (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990),185). Aisha calls Uthman a kafir on one occasion. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVI, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Adrian Brockett (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1997),53). The Alid party of Basrah who fought against the forces of Aisha before they entered into Basrah also blamed Aisha and her associates to be a Kafir. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVI, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Adrian Brockett (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1997),74.

- See above.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 316.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XI, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Khalid Yahya Blankinship (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1993), 187, 188.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Gautier H. A. Juynboll (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 21, 23.

- R. G. Hoyland, “The Content and Context of Early Arabic Inscriptions,” Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam, 21 (1997): 77 – 102.

- M. Kawatoki, R. Tokunaga, M. Lizuka, Ancient and Islamic Rock Inscriptions of South West Saudi Arabia I: Wādī Khushayba, 2005, The Middle Eastern Cultural Centre In Japan And Research Institute For Languages And Cultures Of Asia and Africa, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies: Tokyo (Japan), Pp 9 – 10. And colour plate 2. AND Mutsuo Kawatoko, “Archaeological Survey of Najran and Madinah 2002”, Atlal: Journal of Saudi Arabian Archaeology, 18 (2005), 51 – 52, Plate 8.12 (A).

- Robert G. Hoyland, In God’s Path: the Arab Conquests and the Creation of an Islamic Empire (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 136, 266.

- Sebeos, Sebeos’ History ed. and trans. Robert Bedrosian (New York: Sources of the Armenian Tradition, 1985), 123, 124.

- A. H. Becker, sources for the history of the School of Nisibis, (Liverpool: 2008), 25.

- Robert G. Hoyland, In God’s Path: the Arab Conquests and the Creation of an Islamic Empire (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 266.

- Robert G. Hoyland, In God’s Path: the Arab Conquests and the Creation of an Islamic Empire (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 266.