The most important changes that took place in the whole of the Middle East during the three decades of the Rashidun Caliphate were in the social arena. Muslim society expanded from its original boundaries inside the Arabian Peninsula to the adjacent but vast areas of Asia, Africa, and Europe. Muslim society diversified from its original ‘Arab-only’ form to a ‘multi-ethnic’ form. No doubt, Arab Muslim society retained its original flavour, though it started mixing and mingling with others. Arab elites not only started influencing the culture of conquered nations, but they also started absorbing their cultural elements. The result was the emergence of an entirely new, rich, and vast civilization, later called the Islamic civilization. The Islamic civilization didn’t mature during the three decades of the Rashidun Caliphate, rather, it triggered its initialization.

Islamization of society

The most important measurable change in the Middle East during the era of the Rashidun Caliphate was the Islamization of the society. Historians call the expansion of the area under Muslim rule and conversion of people to Islam ‘Islamization.’1

Invading Arab Muslims offered Islam to each and everybody irrespective of his creed or colour. It can be attested by looking at the variety of people who accepted Islam during the Rashidun Caliphate. They included Persians, Coptic Egyptians, Christian Arabs of Syria, and Berbers of North Africa. 2 However, as Tabari asserts, Rashidun Caliphate presented Islam more forcefully to Arab tribes of the Arabian Peninsula as compared to others.

As incidents of apostasy among conquered people outside the Arabian Peninsula are well documented, one can assume that the commitment to Islam was weak in the new converts.3

The Rashidun Caliphate started using Islamic symbols in statuary materials. Smith and Rassam discovered a coin minted in Sistan in 652 CE during their archaeological excavations in Nineveh. They presented it to the British Museum in 1872 CE. This coin has a typical Sasanian fire altar on its reverse with attendants on either side. At the far left, is the year of issue expressed in words, and at the right is the name of the mint. On the reverse is the typical bust of Yazdegerd with various ornaments. The only innovation is an inscription of ‘bismallah’ in Arabic script on the right margin instead of Yazdegerd’s name in Pahlavi. 4

Earliest Islamic coin, minted at Sistan. 5

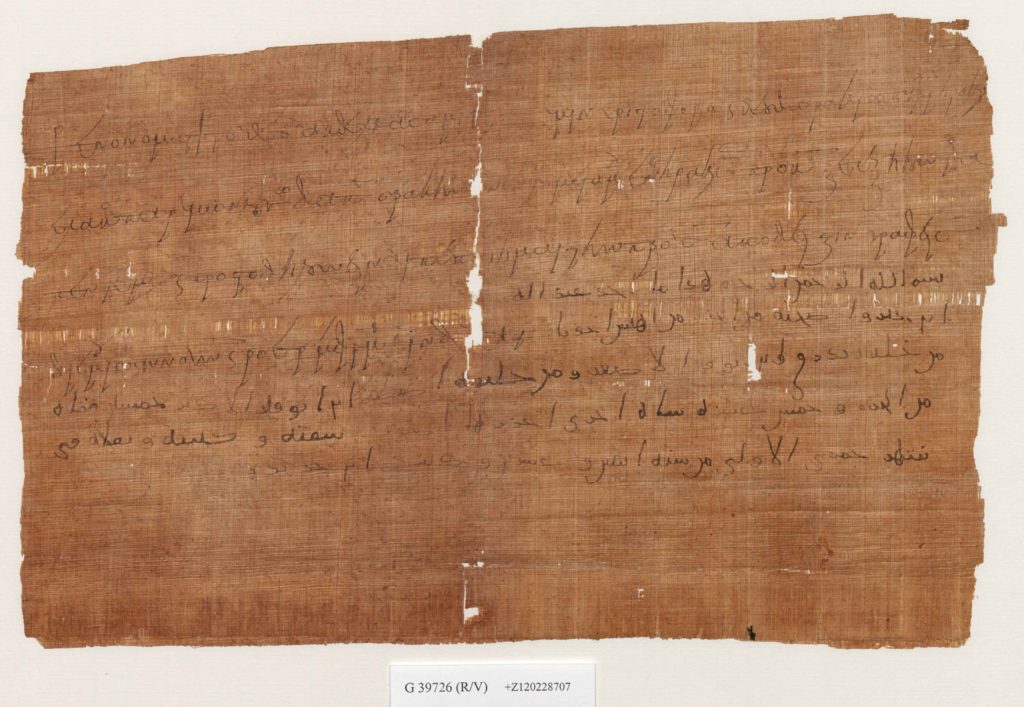

A papyrus preserved in The Australian National Museum, Vienna and dating from 641 CE has bismillah ir Raḥmān ir Raḥīm in its full form written on top.7

Papyrus 558. 8

Language

Language is the most important cementing force for civilization, second only to religion. From the beginning of Futuhul Buldan Arabs kick-started a process called Arabization. It took two forms. The introduction of Arabic in lands where it was not known, and the creation of new Arabic nouns, which later got wider acceptance in other languages. When Arab soldiers reached the territories outside the Arabian Peninsula, they renamed existing places in Arabic for their own convenience. When Arabs saw, for example, a great number of villages, palm and other trees in the Iranian province of Asuristan (Āsūristān آسُورِستان), they exclaimed, ‘Never did we see a greater number of sawād!’ [objects]. Hence the name of the country became Swad.11 When they saw a cliff protruding high among others in eastern Jibal, they named it Sinn Sumairah [tooth of Sumairah].12

The Arabization of words must have not been limited to names of places. Other kinds of nouns must have been coined as well. Initially, new Arabic words were definitely for the convenience of Arabic-speaking people. Later on, gradually, as Arabic became influential in conquered lands, conquered people adopted these words forgetting their own old words.

The introduction of Arabic as an official language was not quick, nor it was universal. The discovery of a document acknowledging the debt, written in Arabic on a papyrus in 643 CE sheds light that Arabic got official status in those areas first where it was already understood.13

Arab conquers were not bent upon destroying the languages of the conquered people. They accepted them as equivalent to Arabic. Greek was written side by side with Arabic in official documents in Egypt and Pahlavi remained the sole official language in ex-Sasanian Iran. 14 Some Arabs, who had linguistic skills, started learning the language of the conquered people to eliminate the need for a translator. Abandoning one’s original language and adopting Arabic was not a condition to convert to Islam. All languages of conquered people survived Futuhul Buldan.

Donner notes that Arabic gained popularity after conquests in those areas where Arab nomads were already living like Iraq, Syria and eastern Egypt.15 This explains the gradual disappearance of Greek from these areas during later times.

Tribe

The tribal identity of each and every Arab individual solidly persisted during the years of the Rashidun Caliphate. When the population of the Rashidun Caliphate extended and it became impossible for everybody to know everybody, a tribal identity card was the only means to recognize a person. Umar asked the lineage of the envoy who came to Medina after the battle of Waj al Rudh to make sure that he was actually the expected person. 16 When government officials captured any unrecognized person, they asked him to produce his genealogy to establish his identity.17 The government still grouped people by their tribal affiliation up to the last years of the Rashidun Caliphate. Ali sent, for example, fifty people of Tamim along with Jariya bin Qudama to tackle the situation in Basrah. 18

The identity role of the tribe remained intact but the significance of the tribe in the lives of Arabs changed significantly. The tribe had lost its role as protector of property, life, and honour in Arab society during Prophetic times. Its use as an instrument of management had begun. The Rashidun Caliphate strengthened the role of the tribe. The fighting capacity of the military of the Rashidun Caliphate and the system of payment to them and other civilians was organized around tribal formations. 19 When the people of conquered nationalities entered into Islam, they got treated like a tribe by the state for the same purpose. 20

Worth noting is that insistence on tribal affiliation had an ideological conflict with tenants of Islam. Initially, Rashidun Caliphate tried to snub it. Khalid bin Walid mixed up different tribes when he arranged his men for the War of Yamama. It didn’t work. Arabs had deep-rooted tribal chauvinism. When the war started, “Muhajirun and Ansar accused the people of the desert of cowardice, and the people of the desert accused them of cowardice, saying to one another, “Organize yourselves separately (imtāza) so that we may shun those who flee on the day [of battle], and may know on the day [of battle] from where we are approached [by the enemy].” So they did that. The settled people said to the people of the desert, “We know more about fighting settled people than you do.” Whereupon the people of the desert replied, “Settled people do not excel at fighting, and do not know what war is; so you will see, when you organize us separately, from where weakness comes.” so they organized separately.21 Then Rashidun Caliphate abandoned the idea of discarding tribal organization. They found it of practical use.

Religion had started becoming an identity among Arabs during the Prophetic time. We hear of people from the same clan, even from the same family, fighting on opposing sides due to religious differences. Now, religious identity became profound and came at equal footing with tribal identity. During the later phase of the Rashidun Caliphate, however, the place of abode attained an important identity marker. We hear of Rabi’a of Kufa and Rabi’a of Basrah during the later years of the Rashidun Caliphate. 22 By the time ‘Amr bin As invaded Egypt to control it for the sake of Mu’awiya in 658 CE, Islamic sources did not bother to report the tribal consistency of his army. They rather report it on the basis of the area of their origin, such as Syria or Jordan.

Beginning of true Arab Nationhood

Though Arab identity certainly existed before Islam, it was the Futuhul Buldan that entrenched it. 23 Arabs wished to maintain their unique identity. They allowed peoples of defeated nations to accept Islam but made sure that they did not adopt the Arab ethnicity.

Inter-ethnic relations

As the Rashidun Caliphate expanded outside Hejaz, it became a multinational country. People of different nationalities and ethnicities did not merge with the invaders. Each group kept living in social isolation from each other as they used to during pre-Islamic times. The Persians who accepted Islam used to live in Kufa. They had their own separate neighbourhood. Arabs called them Himra (Ḥamrā’ حِمراء), the red. They would say, “I came from Ḥamrā’ Dailam”, as they would say, “I came from ‘Juhainah” or some other place. 24

The Rashidun Caliphate didn’t recognize ethnicities and nationalities at an official level. The ethnic origin of a person was not documented in any register. The official classification of citizens of the Rashidun Caliphate was Muslims and non-Muslims. Umar said in his last year, “I will treat people equally and not favour a ruddy (aḥmar) person over a swarthy one or an Arab over non-Arab. I will do as the Messenger of Allah and Abu Bakr did.” 25 i.e. he would treat all Muslims equally irrespective of their ethnic origins and would treat non-Muslims separately from Muslims.

The existence of multiple nationalities and ethnicities in the Rashidun Caliphate was, in any case, a fact which could not be neglected. Arabs were triumphant. They were conscious of their superiority. They looked down upon the defeated people, specifically those who did not accept Islam. They were called Dhimmi, which became a kind of racial slur. The colloquial word for the census of Dhimmis was ‘attaching seal around their neck’. 26 Look at the wording of the truce agreement written between Habib bin Maslama and the inhabitants of Tiflis: “This is s statement from Ḥabīb bin Maslamah to the inhabitants of Tiflīs ….. securing their safety for their lives, churches, convents, religious services and faith, provided they acknowledge their humiliation and pay tax to the amount of one Dīnār on every household.” 27

Arabs clinch cultural elements from the defeated

No historian has the slightest doubt that the formation of Islamic civilization did not result from the imposition of Arab culture upon the defeated nations. It resulted from the mingling of Arab culture with the local cultures of defeated nations. The Arabs were rulers and their culture was no doubt the dominant one. However, they themselves picked cultural elements from others. The process started the very day they came into contact with others on a large scale. As no source mentions the use of ornaments in Arab men during pre-Islamic and Prophetic times, we can assume that Arab men didn’t use ornaments. Contrary to this, Iranian men used to wear brocaded garments and jewelry. 28 Nā’il bin Ju’shum was a soldier fighting the Battle of Qadisiyyah from the side of the Rashidun Caliphate. He killed an Iranian by the name of Shahriyār and captured his bracelet. Na’il was so fascinated by it that his commander Sa’d bin Waqqas allowed him to keep it wearing until the battle was over. The scene was so unusual for the Arabs that it survived in traditions and Tabari had to note that Na’il became the first Muslim in Iraq to wear a bracelet. 29 This is a classic example of invaders adopting the culture of the invaded.

In the beginning, when the Arabs and Persians came into contact with each other their attires were distinguishably unique. An Arab soldier could easily deceive the Iranian side by putting on Persian attire during the war in Fars in Umar’s era. 30 The situation changed dramatically later. Some Arabs started wearing Persian attire on a regular basis. Tabari specifically mentions that an Arab soldier of Ali’s army on the way to Siffin used to wear qalansuwah, which was a typical Persian headpiece. 31

Moral standards

Muru’ah, the moral standard of pre-Islamic Arabs remained unchanged among Arabs. They took it wherever they reached. During campaigns, for instance, Arab soldiers used to split into groups of seven to ten, make a circle and eat together.32 The defeated nations had their own moral standards. Muru’ah and the moral considerations of others started mingling during the era of the Rashidun Caliphate to develop a new moral standard in the Middle East, with wider application than Muru’a previously.

Justice System

Rashidun Caliphate had multiple criminal justice systems working side by side. Each religious community used its own justice system. 33 Here, we are only concerned about the Islamic justice system. The Rashidun Caliphate appointed judges (sin. Qāḍī Pl. Quḍḍah) in all main cities. The judiciary was separate from the administration at the provincial level. Each provincial capital had its own judge as well as governor. For example, Khārijah bin Ḥudhāfah of the Sahm clan was the judge of Egypt during Umar’s time and Amr bin As was governor. Uthman retained both of them in their offices after assuming power. 34 One person never got the two offices simultaneously. Judiciary was not under the authority of local governors and was directly responsible to the caliph who was the chief justice of the country by default. The town of Medina had its own judge. The judges decided the cases according to Islamic law. They had to be better versed in the law than to be loyal to the government. We hear of certain judges who served under many successive governments.

The rulers of the Rashidun Caliphate were conscious that the combination of the chief judge and chief administrator in the same person creates technical difficulties for the transparent delivery of justice. Umar used to carry a whip in his hand. Once, he whipped a person unjustifiably in a bout of anger. That person didn’t bring any claim against Umar. Umar ordered an injunction against himself and paid the aggrieved six Dirhams as compensation. 35

As different communities lived in social isolation, the legal question, ‘Which legal system would deal with a person if he commits a crime against a member of a different religious community?’, remained irrelevant.

The Rashidun Caliphate kept the death sentence on its statuary law code. According to Tabari, only three crimes carried a death sentence. They were murder, adultery, and apostasy against Islam. 36 Tabari notes that certain political activists had been calling for the death penalty against political miscreants (mufsid) They used to present verses of the Qur’an in favour of their demands. 37 The state, anyhow, neglected these calls.

Worth noting is that, according to Tabari’s report mentioned above, blasphemy against Prophet Muhammad or against Islam did not carry a death sentence during the Rashidun Caliphate. A detailed survey of all available historical sources fails to depict a single incidence of justified homicide for blasphemy. We find out many contracts between Muslims and non-Muslims from the very beginning of Futuhul Buldan which specifically bound non-Muslims not to ridicule Islam as a religion. Any ridicule of Islam from one of their members would have been considered a break of contract. In that case, the only action Rashidun Caliphate used to take was to compel them to renew the contract. We don’t hear of a single example where a contract was considered broken due to blasphemy against Prophet Muhammad or Islam during the time of the Rashidun Caliphate. Historians have discovered many documents written by non-Muslims during the time of the Rashidun Caliphate that were derogatory to Prophet Muhammad. 38 It gives a clue that even if a non-Muslim committed blasphemy, the state neglected it provided he kept it to his religious fellows.

No Muslim was accused of blasphemy towards Prophet Muhammad or Islam during the Rashidun Caliphate. Probably, if anybody did so, he was considered apostate and dealt with accordingly. 39

Apostasy carried the death sentence. However, all apostates got an option of repentance and reverting to Islam before any verdict against them. All people of Abdul Qays got pardoned for accepting Islam again when they were apostatized to their original Christianity during Ali’s time. Only one of them, an old man, refused to convert back to Islam. He served the death sentence according to the law. 40

During Prophetic times, the murderer was personally responsible for the crime. The citizens of the Rashidun Caliphate wished for amendment in the law. They started thinking that accomplices of murder should also be charged with the crime. These sentiments surfaced at the time of the murder of Umar. They got widespread after the murder of Uthman and were still present at the time of the murder of Ali. 41 The Rashidun Caliphate didn’t take any steps to extend the responsibility of murder to the accomplice of the crime.

Adultery definitely carried the death sentence during the Rashidun Caliphate. Ya’qubi documents a case of death sentence for adultery. 42

The legal way of carrying the death sentence was to cut off the head with a single stroke of a sword publicly. 43 The state had not hired headsmen. The family of the slain got possession of the culprit after a verdict by the state court. One of the family members carried out the sentence. Probably, this mechanism satisfied the pre-Islamic desire to restore the honour of the family by avenging the death personally. The only exception to death by beheading was adultery. Its culprits were stoned to death. Community carried out this punishment collectively. Examples of other ways of killing are present. Once, Abu Bakr burnt a law fugitive alive. 44 However, unusual ways of justified homicide did not get universally accepted. Abu Bakr had to repent for burning a criminal alive. 45

The Sasanian Iranian custom to amputate a person and jailing him for a while before serving a death sentence didn’t enter into Islamic legal codes. Along the same lines, we find that sometimes Byzantine Romans of that time used to throw a condemned culprit in an arena to fight with a lion to face his death. 46 No such activities crossed over to the Justice System of the Rashidun Caliphate.

Death was not the only sentence for murder. The facility of dyat was there. During the caliphate of Uthman, Fartanā was murdered. Uthman granted a judgment of eight thousand Dirhams. Out of them six thousand as blood debt and two thousand for the harshness of the crime as the murderer killed her by breaking her ribs. 47, 48

The Rashidun Caliphate succeeded in awarding a sentence of murder without any exemption during its first half. People were afraid of being accused of murder. Rūzbih, a new Muslim of Persian ethnicity, was on his way back to Kufa after accepting Islam in Medina during Umar’s time. He died on the way. The ‘ibād (Christian residents of Hira) camel drivers, who were carrying him didn’t bury him immediately. They waited until a group of Bedouins passed by whom they showed his body and the Bedouins confirmed that the death was natural. Only then they buried him. 49

Flogging, which had started during the Prophetic time, remained a way to punish criminals for certain offences. Pre-Islamic Arabs used to banish a person from the community (exile). Its use increased many folds during Uthman’s tenure, particularly against political dissidents. 50 Uthman didn’t have any laws under which he could charge them.

A new kind of punishment, which became part of the legal code, was imprisonment. There are examples of imprisonment during pre-Islamic times but the state didn’t imprison anybody during the Prophetic times. The Rashidun Caliphate gradually established proper facilities for jailing a person. Explaining the name of a Jail in Medina Baladhuri tells that it was actually the house of Abdullah bin Siba (‘Abdallah bin Sibā’ عَبداللَّه بِن سِباء). Hamza Bin Abdul Muttalib had challenged Abdullah’s father Siba during the Battle of Uhud. 51 In this sense, Abdullah bin Siba must be of that generation who immigrated to Medina after Fath Mecca. It means it was the Rashidun Caliphate which used his house as a jail.

Thieves were punished with the amputation of their hands. 52 It was a hazardous sentence as a person in bad shape of health might die of it. Exactly this happened when Ali carried out this sentence on a Christian named Hulwan (Ḥulwān حُلوان) from Taghlib. He was a secret courier of an ally of Mu’awiya. In his case, the next of kin of the culprit got compensation for murder from the person who had hired him as a courier. 53

Imposing a fine and confiscation of property for financial crimes committed against the state treasury became prevalent during the Rashidun Caliphate.

Civil cases about disputes regarding immovable property were rare. Mostly courts had to hear disputes over the distribution of booty. They were so many that Rashidun Caliphate had to appoint Abdur Rehman bin Rabi’a (‘Abd al Raḥmān bin Rabi’ah عَبدالرحمان بِن رَبِيعَه) of Bahila tribe as a special judge of appeals in cases of spoils of Qadisiyyah. 54

For all cases, criminal or civil, only two witnesses were needed except for the crime that carried the sentence of stoning to death. At the time of the conquest of Iraq, Khuraim bin Aws of the Tayy tribe claimed that he had asked the Prophet, “If Allah enables thee to reduce Ḥīrah, I shall ask thee to give me Buqailah’s daughter.” So Khraim pleaded to Khalid bin Walid to keep Buqailah’s daughter out of the peace contract. Khalid asked for two witnesses. Bashir bin Sa’d (Bashīr bin Sa’d بَشِير بِن سَعَد) of Ansar and Muhammad bin Maslama of Ansar testified (two men). She was, therefore, not included in the terms. She was turned over to Khuraim. 55 The requirement of at least two witnesses to prove a case in a court of law was the gold standard in the Middle East even before Islam. Sebeos describes a case of slander which got judged due to the testimony of two witnesses.56

Taking oath by Allah was admissible in a court of law from a Muslim in his defence. It was particularly applicable when the prosecution didn’t have any eyewitnesses and tried to build a case on circumstantial evidence. During the re-conquest of Ubullah an Arab soldier, by the name of Salmah, got awarded a copper pot as booty. Later on, he found eighty thousand mithqāls of gold inside the pot. People suspected he might have acquired that gold from the booty by stealth or fraud. The case ended up with Umar. Umar asked the local commander to ask for a solemn oath from Salmah in the name of Allah that he didn’t know what was inside the pot on the day he received it. If he takes the prescribed oath, the case would be dismissed, if he doesn’t the said property would be confiscated and redistributed among participants of the battle. 57 Qays bin Makshuh defended himself successfully in the murder case of Dadhawaih, the leader of Abna’, by taking fifty oaths near Prophet’s pulpit for his innocence in Abu Bakr’s court. 58 The prosecutor didn’t have any eyewitnesses but the circumstances of the crime suggested Qays was the murderer.

Once a person served the legally prescribed sentence, he automatically got rehabilitated fully. He could get a government job and courts accepted him as a reliable witness. 59

Crime was rare in Muslim Arab society, at least in the early part of the Rashidun Caliphate. Salman bin Rabi’a (Salmān bin Rabi’ah سَلمان بِن رَبِيعَه) was the first judge of Kufa, where he spent forty days without hearing a single case.60 As the political organization of the Rashidun Caliphate crumbled, the graph of the crime rate started rising. Islamic sources document street fights in Kufa during Ali’s tenure for petty disputes.61 It is hard to find its parallels in earlier governments. Not only this, organized crime cropped up in the society. It originated from Kufa when thugs dug a tunnel to steal from the provincial treasury during Sa’d’s first governorship there. The culprits could not be apprehended.62

Lack of privacy

Soon after the founding of cantonments, it appears certain citizens kept an eye on others to find their faults. It could be due to expectations of society as a whole to eradicate crime or it could be a strategy to entangle an opponent in a legal trap. Common people were fed up with the situation. Once, an accused asked the court while defending himself, under which law his neighbour was allowed to use his house to spy on him. 63 Administrators and religious authorities were aware of the annoyance. Once, Abdullah bin Mas’ud, in his capacity as wizir of kufa and as a renowned religious scholar said, “If a man hides something from us, we do not pursue his flaws nor tear open his veil.” 64

Rules of war

The people of Sasanian Iran and Byzantine Rome must have got a set of rules that applied to their wars, just like the Arabs had. We don’t know how strictly war rules were applied in the battlefields. Evidence is scanty on this issue. During the re-conquest of Ubullah, both armies agreed that the Muslims would cross the river by means of rafts for a fight and the Persians would abstain from attacking them in this vulnerable situation. Persians actually allowed them to complete the crossing safely. 65

Poetry

Poetry was the soul of Arabian culture during pre-Islamic times. It maintained its appeal. It not only survived but also thrived. Umar used to recite poetry to his friends. 66 Qasida (Qasīdah قَصِيدَه), rajz (رَجز) and other pre-Islamic styles of poetry remained popular. The themes of poetry didn’t change much.

Look at a rajz composed by Dirar bin Azwar (Ḍirār bin al Azwar ضِرار بِن الاظوَر) about the Battle of Yamama:

So if you seek unbelievers free of blame,

[Oh] south wind, indeed I am a follower of the faith, a Muslim

I strive, because striving (jihād) is [itself]

booty, and Allah knows best the man who strives.67

A qasida for wine by Abu Mihjan (Abu Miḥjān ابُو مِحجان):

When I die, bury me at the foot of a grapevine,

so that its roots will moisten my bones after death.

And do not bury me in the desert,

for I fear I shall not taste [the juice of] the grapevine after I die.68

Poetry remained the most powerful medium. The government had to keep an eye on what poets said and censure them if the need arises. 69

Dwellings

Arab Muslims had amassed a tremendous amount of wealth through Futuhul Buldan but the central government didn’t allow them to display their wealth publicly. Once Umar died and Uthman changed the government policy, people started building luxurious villas in Medina. All were custom-made and professionally designed. The purpose was to show off while enjoying all the possible comforts life can offer. 70

The housing bonanza in Medina was not an isolated pattern. The standard of dwelling places improved tremendously for the Arab elite all over the country. Many early companions of Prophet Muhammad built houses that amounted to palaces in Arab’s eyes. The common Arabs were not less fortunate. Those who used to live in basic houses built of brick and stone got a chance to live in properly planned cantonments. All neighbourhoods in cantonments had a wide leading lane. Inside lanes were wide enough to carry the load of traffic. Each neighbourhood had its own mosque and market. Running water was available in houses. The building codes and city bylaws regulated the living conditions of towns.71

When Arab armies reached the capitals of conquered countries and provinces, they didn’t utilize existing palaces. Probably, they had theoretical problems here. All members of invading army were equal. Military ranks allocated to individuals for that particular battle had no permanency. They did not find anybody among them befitting royal palaces.

Cantonments became cosmopolitan centers

The richest group of people, probably in the whole world, used to live in Cantonment towns during the latter half of the Rashidun Caliphate. This group created a lot of jobs. The demand for jobs could not be fulfilled by the labour market of the Rashidun Caliphate. Job seekers from foreign countries poured into cantonment towns. This is particularly true for Basrah where a number of people had come from Sind and India. Tabari denotes two groups of people. One was Zuṭṭ, who are recognized as Jutt (Jatt) from North India. 72 Others are Sayābijah who could be originally from Sind. They mainly got employment as watchmen and doorkeepers. 73

Change of dwelling place

As the volume of the Rashidun Caliphate expanded, many Arab families were split. Their members got government jobs at a distance from each other. They always wished to live nearby each other as family bonds were strong. Samit bin Aswad (Samiṭ Bin Aswad سامِط بِن اسوَد) of the Kindah tribe was in charge of allotting vacant houses to his people in Homs. After Battle of Yarmouk his son Shurahbil (Shuraḥbīl شُرَحبِيل) had a dispute over leadership of the Kindah tribe in Kufa with his fellow tribesman Ash’ath bin Qays. Samit applied to Umar to either transfer Shurahbil’s services to Homs or Samit’s services to Kufa, so both could join each other. Umar transferred Shurahbil to Homs. 74

Future telling

Whichever decision we make, it is about the future but we make it in present. Suspense to know the future is almost universal. Many businesses thrive on this suspense. On his way to Naharvan, Ali met an astrologer. He insisted on foretelling about his success. Ali didn’t pay heed to him and rejected his advice. 75

Entertainment

The domain of entertainment of Arab Muslims during the Rashidun Caliphate is tricky. Muir observes that regular payment of stipends from the government would have created a kind of idleness in early Muslim society. 76 Venues of entertainment usually attain paramount significance in such societies. Historic sources are not very helpful in picking the entertainment domain of Arab Muslim society during the Rashidun Caliphate. Certain pre-Islamic ways of entertainment, for example, poetry, transferred into the society of the Rashidun Caliphate in toto. Others became controversial. We hear anecdotes of hunting for pleasure in certain circles of Arab elites. Dabi bin Harith (Ḍābī’ bin Ḥārith al Burjumi ضابِيع بِن حارِث) used to hunt in the province of Kufa, using a hound during the governorship of Walid bin Uqba. 77 As we don’t find it as a regular pastime of the Muslim elite, it appears that this was a hobby which was frowned upon. The art of singing persisted in the society, however pious were expected to abstain from it. 78 Umar is specifically recorded to hate listening to music. 79

Horse racing lingered on in the Rashidun Caliphate, just like in Prophetic times, as a main source of entertainment for the elite. Uthman bought an expensive horse to use in the races during his caliphate. 80 Salman bin Rabi’a of the Bahila tribe was in charge of a group of people responsible for keeping cavalry horses in Kufa. He used to organize horse races year-round. 81

An interesting anecdote about the entertainment of Arab Muslims comes from Kufa. Ibn Dhial (Ibn Dhīal Ḥabakah al-Nadhi اِبن ذِيال هِبَكَه النَذِى) used to perform magical spells (nīranj). Uthman asked his governor of Kufa Walid bin Uqba to interrogate him and, in case it is true, to punish him. The magician replied, “It is just sleight of hand, something to amuse people.” Walid ordered him to be severely chastised. People turned against Uthman and wondered about his concerns about matters of this kind. 82

Manners

Every society possesses its own set of manners, which represent socially acceptable etiquette. While the culture may not impose punishment for failing to adhere to these norms, it can lead to a decline in popularity for the individual in question. Umar, as a leader, held the expectation that his governors would demonstrate compassion by visiting the sick, regardless of their social status, and not allowing the weak to wait at their doors. 83 Respect for seniors was of paramount importance. Age was the main factor which determined seniority among a given group of people. Interrupting the speech of an aged senior was considered a very bad manner. 84 During the pre-war meeting of the Battle of Nahavand, Tabari notes, people expressed their views turn by turn with age senior first and age junior last. 85 Similarly, people didn’t see any harm in expressing respect for a socially senior person. When people saw Ali passing in public pathways of Kufa, they used to move aside from his front to give him a way as a gesture of respect. 86 Expression of such hierarchal respect can be observed when people met each other. Hāshim was a junior commander in the army of the Rashidun Caliphate. When he came to meet his boss Sa’d bin Waqqas he kissed Sa’d’s foot. In return, Sa’d kissed Hashim on the head. 87 When Amr and Shurahbil reached Jabiya to pay a visit to Umar, the latter was already ready to leave. They kissed Umar’s knee, and Umar embraced them, holding them to his chest.88

Manners of Arabs regarding showing respect to others might be different from other nations. The Arab delegate sat in the same place where Rustam was seated during pre-war negotiations at Qadisiyyah. The Iranians minded it. The Arabs answered that the Arabs don’t mind it as they treat each other equally. 89 Seemingly, Arabs knew how Persians showed respect to each other and they insisted on acting according to their own cultural values.

Abusive words

Almost all cultures retain abusive words. They are needed for appropriate expression of anger and disdain. The Arab society of the Rashidun Caliphate, like that of Prophetic times, kept its abusive words revolving around the theme of sexual misconduct. “You son of a slut!” shouted a man of Abdul Qays on Hakim bin Jabala (Ḥakīm bin Jabalah حَكِيم بِن جَبَلَه) when Hakim swore at Aisha in her absence. 90

Almsgiving

Almsgiving is not limited to any era or any nation. Each culture admires this voluntary act. The point to make here is that Muslim Arabs of the Rashidun Caliphate didn’t mind giving to non-Muslims. When Mu’awiya’s admiral (wa’sta’mala ‘alā al-baḥr), ‘Abdullah bin Qays ended up in a Byzantine fishing village because his light boat (qārib) separated from the main fleet, many beggars surrounded him. Probably they mistook him for a king or a rich merchant. He gave alms to each of them. One of them was a woman. He gave alms to her as well. 91

Alcohol drinking

Wine drinking among elite Arabs during the era of the Rashidun Caliphate needs special attention. We don’t hear of any case of wine drinking during Abu Bakr’s caliphate. Either no Muslim drank alcohol during his time or he neglected such behaviour. The tussle of the state against wine drinkers started during Umar’s caliphate. Umar was really furious when he received intelligence reports that some Muslims living in Syria regularly indulged in alcohol drinking. One of them was Abu Jandal, who used to justify it by saying that wine drinking is not prohibited in Islam. Umar summoned him to appear before a jury of Muslims, comprised of local residents of Syria, to get his statement on this matter recorded. He instructed the jury if Abu Jandal maintains that alcohol drinking is not forbidden in Islam, he should be sentenced to death. 92, 93 Here, Umar’s point of view was that ban on alcohol drinking is clearly a Qur’anic injunction. If somebody doesn’t accept it, he rejects the Qur’an. Hence he is committing apostasy, which was punishable by death. Abu Jandal admitted to the jury his full knowledge of the Qur’anic proscription on alcohol drinking. Then Umar convened a round table conference in Medina of those Companions of Prophet Muhammad who had a repute of being well-versed in religion. They unanimously prescribed that a wine drinker should be flogged forty times in public. 94, 96 Actually, flogging was so insulting a sentence that Abu Jandal and his co-culprit in the crime Ḍirār appealed to get a chance to participate in the war against Byzantine before the sentence is carried out. Both of them preferred death in war to flogging. Ḍirār died in the battle but Abu Jandal survived. Governor Abu Ubayda wrote to Umar that Abu Jandal was depressed. He hoped reduction or postponement of sentences on the basis of sickness. However, Umar wrote back that he should rather repent and ask for the forgiveness of Allah, and insisted on carrying the punishment in full and in a timely fashion. 97

Before this incident, which would have taken place no later than 639 CE, alcohol drinking was definitely frowned upon by Muslims. Still, there was no universally agreed punishment for it. Once, Sa’d bin Waqqas flogged and imprisoned his soldier by the name of Abu Mihjan of Thaqif for alcohol drinking before the Battle of Qadisiyyah (638 CE). Abu Mihjan requested the guarding concubine to free him temporarily so he could participate in jihad. He fought in the war so bravely that Sa’d pardoned him of his crime. 98 This Abu Mihjan had been exiled by Umar previously for wine drinking. He escaped from exile somehow. 99

After the court case of Abu Jandal versus the state, Umar used to flog the dignitaries of the Rashidun Caliphate for wine drinking on an almost regular basis. 100 Since that time, no Muslim ever had the courage to publicly deny forbidding alcohol drinking in Islam. Anyhow, Umar’s strictness didn’t eradicate wine drinking by Muslims. They changed their method of committing delinquency. They knew that any prosecutor needed two reliable eyewitnesses to prove the crime. They shifted the venue of alcohol drinking to their homes. They invited only those to participate who wished to join the party so nobody could be a reliable witness. It seems that practically Muslim society is split into opinions regarding alcohol drinking. There were pious people who believed that alcohol drinking is a punishable crime. Others justified their alcohol drinking by arguing that it is only a sin and Allah is Merciful in any case. Since then attitude towards alcohol drinking serves as a litmus test between pious and profane Muslims.

Tabari informs us that during the later years of Uthman’s caliphate alcohol drinking became commonplace among Muslims. The state found itself helpless to eradicate the menace.

Umar remained alert throughout his tenure lest somebody make him drink alcohol by deception. During his state visit to Syria, Amr bin As brought a beverage for him called locally ṭilā. Umar consumed it after assuring that it was not alcohol. He specifically asked how it is made and drank it only after he got convinced that there was no harm in it. 101

Festivals

The Muslim festivals of Eid Adhha (‘Īd al Adhḥā عِيد الاضحىٌ) and Eid Fitr (‘Īd al Fiṭr عِيد الفِطر) gained new dimensions during the Rashidun Caliphate decades. Previously, Arabs used to live with all their kith and kin nearby. Nobody had to travel to celebrate the occasions with his family and friends. Now, Arabs were scattered all over. They used to travel long distances to celebrate the festivals with their next of kin. When a soldier of Ali found the camp established by Ali to organize a fight against Mu’awiya deserted, he equated it to the towns which Arabs empty before Eid festivals. 102 People were expected to gather in a central open place of the town to pray for both Eid festivals. 103

As Muslim Arabs didn’t interfere with the internal affairs of defeated nations, their festivals persisted. Christmas and Nauruz both survived the Muslim invasion. Tabari records an interesting festival of Mihragān, which people of Balkh observed when a battalion of Rashidun Caliphate was there in the winter of 652 CE. They used to give precious gifts to their ruler on this occasion and were unsure if the commander of the Muslim army would accept them. One of the petty commanders accepted their gift. 104 Humphreys points out it could be the ancient Iranian festival of Mihr, which used to be celebrated on October 26 each year. 105

Costumes

As cultures mingled, so did their costumes. The defeated used to pay part of their poll tax in the form of dress. Egyptian dress was acceptable to the government. It means Arabs started using it.

Apparently, the clothes of early Muslims were made up of cheap materials. They were aware of extravagant materials for preparing clothes but they themselves didn’t bother to use them. During Futuhul Buldan, Muslims started showing their attraction to such luxuries. Umar reprimanded commanders for wearing silk and brocades at the time of his meeting in Jabiyah. Later, he accepted their apology that they were wearing weapons as well. 106 Umar’s dislike for showy wearing materials was so extensively known that, according to Tabari, Muslim participants of Yarmouk didn’t consider wearing silk lawful. 107

Umar was particularly thrifty about clothing. Once, Abdullah bin Umayr threw away his old clothes. Umar advised him to use the new garments for looking smart and keep the old ones to serve when he is within the family. 108

Covering the head was a social compulsion for both men and women. As the turban was a formal dress and wearing it all the time was bothersome, men used to cover their heads with a robe.109

Fashions of life

Few anecdotes have survived which depict the styles of people during Rashidun Caliphate.

Generally speaking, early Arab Muslims, who came into contact with many other cultures as a result of Futuhul Buldan were the most simpleton creatures. When they found camphor in Tyswn after its capture they mistook it for salt and put it in their pans. 110 The anecdote highlights their innocence. Arabs used camphor in their death rituals before the advent of Islam. 111 Yet, many of them didn’t recognize it in its pure form. They didn’t even smell it before using it in their food.

On the same line, the diet of Arab Muslims, especially those around Umar, remained simple and basic. Arabs used to boil water and put flour into it gradually while stirring to make dough which they ate. 112 Here is a typical menu which Umar used to offer to his guests: baked bread, olive oil, coarsely ground salt, and lightly sweetened water mixed with certain ground grain. The soldier whom Umar served this food for lunch and who reported the incident says that he was unable to palate it. He complains that he had got better food at the borders. 113 Special recipes were definitely available to Muslim Arabs but probably they were not their staple food. Tabari informs that older men of Quraysh were passionately fond of Khazīrah. It was made from the best-cooked meat. It contained sheep’s stomachs and a broth made of milk and fat.114

Cleaning teeth was a simple affair. They used to bite on a root and then rinse the mouth with water. 115 The rich had special means to keep oral hygiene. Uthman had teeth braced with gold.116

Death rituals

In the end, a glimpse of rituals around death. Details of the death and burial of Abu Dharr are well documented. When Abu Dharr reached his final moments in Rabadha, he instructed his wife and a slave to wash his body, wrap him in his burial shroud, and place him on the surface of the road. He further instructed them to approach the first passing caravan, inform them of his identity, and request their assistance in burying him. 117 They turned their head toward qibla after his death. Hudhayfa bin Yaman and Malik bin Harith al Ashtar prayed over him. 118 When Uthman heard of his death, he said “May Allah have mercy on Abu Dharr.” 119 Dressing a person in three robes without a qamīs for burial was standard practice. This is exactly what Ali got. 120 The funeral prayer was special. The funeral of Ali had nine Takbīrahs. 121

Not everybody got the same treatment at death as Abu Dharr or Ali. After decapitating Ibn Muljam, the assassin of Ali, people wrapped him in some straw mats and set fire to him. 122

Condoling a death was the most important social duty around death. Suhayl bin Amr’s young son by the name of Abdullah died in the Battle of Juwātha at the age of thirty-eight years. When Caliph Abu Bakr met Suhayl during the Hajj season that year, he spared time out of his schedule to comfort him. Suhayl said that his son would hopefully intercede with him through Allah.123

Visiting the grave of the dead at least once and expressing sorrow was an extension of condolences. Utba bin Ghazwan, Umar’s governor of Basrah, had died during travel from Medina to Basrah and was buried by the road. When Umar got a chance, he visited his grave. On that occasion, he praised Utba for his merits.124

Pre-Islamic Arabs were not very particular about the place where the dead should be laid. Sometimes they buried the dead in the house he died. Abdullah bin Abdul Muttalib was buried in the house of Medina where he had died. 125 Medina didn’t have any graveyard before the immigration of Muslims there. Muslims started Baqi (Baqī’ بَقِيع) when they buried Uthman bin Ma’zun (‘Uthmān bin Maz’un (عُثمان بِن مَظعون to make the first grave there. 126 The city planners of Kufa didn’t designate a graveyard for Kufa. People used to bury their dead in their own courtyards. It was only during Ali’s abode in Kufa that the graveyard appeared. People started burying dead outside the town, and it grew into a graveyard. 127

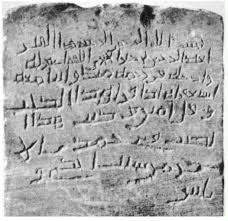

We are skeptical about the use of funerary inscriptions by Muslims during Prophetic times. Now, we find such funerary inscriptions. The Museum of Arab Art in Cairo carries a tombstone of a certain Abdur Rehman bin Khair, (‘Abd al Raḥmān bin Khair al Ḥajri عَبدالرحمان بِن خَير الحَجرِى) who died in February of 652 CE. It contains bismillah in full form on top and a prayer for the mercy of Allah on the diseased. 128, 129

Tombstone of Abdur Rahman ibn Khair al-Hajri. 130

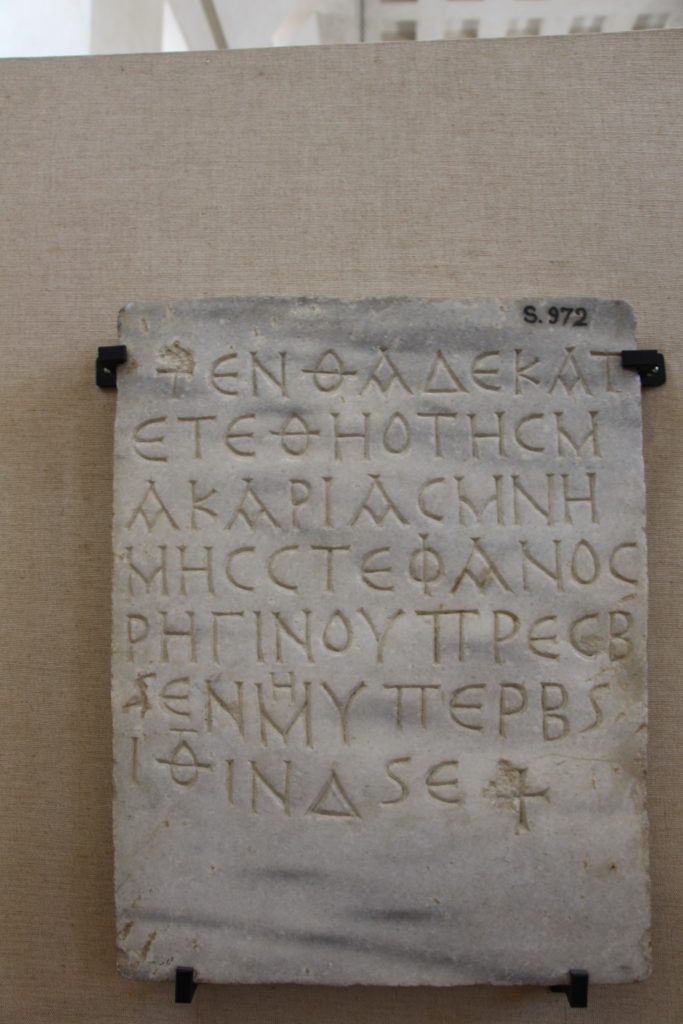

A Christian tombstone written in Greek on marble from the 6th century CE from the Beersheba district. 132

As communities were divided into religious lines, usually only those people who attended the death rituals of a diseased who belonged to the faith of the diseased. When Ibn Muljam saw some Muslims attending the funeral procession of a Christian by the name of Abjar bin Jabir (Abjar bin Jābir ابجَر بِن جابِر) of the ‘Ijl tribe in Kufa, he couldn’t believe his eyes.135, 136 Probably, the neighbors and friends of a diseased person from a different faith condoled his family in private after the rituals were over.

End notes

- G. R. Hawting, The First Dynasty of Islam, (London: Routledge, 2000), 1.

- See above.

- For apostasy among new converts during the later phase of the Rashidun Caliphate see above.

- Walker catalogued this coin and documented its transmission. See: John Walker, A Catalogue of the Arab-Sassanian Coins, (London: The British Museum, 1941), 4, coin number 8, Pl. 1.7.

- In Private Collection. For details see: H. Gaube, Arabosasanidische Numismatik, Vol II, (Braunschweig, Klinkhardt & Biermann, 1973), 19 – 22, 26 – 34. AND Album & T. Goodwin, Syllogue of Islamic Cons in the Ashmolean – The Pre-Reform Coinage of the Early Islamic Period, Vol. I, (Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 2002), 6 – 7.

- Al-Jabburi, S. Y. Aṣl al-khaṭṭ al- ‘arabi wa-taṭawwuruhu ḥatta nihayat al- ‘aṣr al-umawi (Baghdad: 1977), 98. Both are kept in an Iraqi museum. Numbers 4072 and 4073.

- M. Tillier and N. Vantheighem, “Recording Debts In Sufyānid Fusṭāt.: A Re-examination Of The Procedures And Calendar In Use In The First/Seventh Century”, in Geneses: A Comparative Study Of the Historiographies Of The Rise Of Christianity, Rabbinic Judaism And Islam, ed. J Tolan, (London: Routledge, 2019), 148 – 188. Papyrus 558, mentioned previously and hailing from 643 CE also has this formula written in full form. (Adolf Grohmann, ‘Apercu de Papyrologie Arabe” Etudes De Papyrologie, I. (Cairo: Societe Royale Egyptiene de papyrology 1932), P 40 – 43, Vol. I).

- Current location The Austrian National Museum, Viana (PERF 558). A. Grohman, From the World of Arabic Papyri, (Cairo: Al-Maaref Press, 1952), 113 – 115.

- See above.

- Pre-Islamic Arabs used to write bismillah on top of their documents. Hoyland suggests that bismillah in Arabic is a perfect translation of Greek en onomati tou theou (in the name of God) which was already being written on documents in Byzantine Rome. This practice was established by an edict of Emperor Maurice (580 – 602). See: Robert G. Hoyland, In God’s Path: the Arab Conquests and the Creation of an Islamic Empire (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 101. Muslim Arabs wrote the full formula of bismillah wherever space allowed them.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 463.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 479.

- Adolf Grohmann, “Apercu De Papyrologie Arabe”, Etudes De Papyrologie, Tomme Premier, (Imperial de L’Institut Fancais d’Acheologie Orientale, 1932), 44. Current location: Staatsbibliothek, Berlin. Accession No. P. Berol. 15002.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 466.

- Fred M. Donner, “The Role of Nomads in the Near East in Late Antiquity (400 – 800 C.E.),” in Traditions and Innovation in Late Antiquity. Eds. Clover F.M. and R. S. Humphreys, (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1989), 28.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. Rex Smith (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994), 22.

- See example: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. X, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Fred M. Donner (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1993), 144.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 169.

- Ali and Mu’awiya organized their armies in tribal platoons during the Battle of Siffin to encourage them to fight steadfastly and remain concerned about protecting their tribal honour. See: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 60.

- See for example, Ḥamrā’ Dailam of Kufa. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 441.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. X, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Fred M. Donner (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1993), 122.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 59.

- Robert G. Hoyland, In God’s Path: the Arab Conquests and the Creation of an Islamic Empire (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 61.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 441.

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 785.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 430.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 316.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Gautier H. A. Juynboll (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 212. For extensive ornaments found on the body of Iranian commander Jālīnūs when he got killed in war see: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Yohanan Friedmann (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1992), 128.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Gautier H. A. Juynboll (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 6.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Gautier H. A. Juynboll (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 144. Actually, many ethnicities in the Middle East had completely distinct attire. The shirt of ‘ibādi [Nestorian Christian, living in Swad] was different from that of an Arab to the extent that the Arabs didn’t know its price. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Yohanan Friedmann (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1992), 32.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 6.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 179.

- Justinian I had promulgated the last acts of law in Byzantine Rome between 529 and 534 CE. They constituted the criminal code of the land when Arabs occupied the eastern part of Byzantine Rome. They remained applicable to the non-Muslim population of that region. For the laws see: Fred H. Blume The Codex of Justinian: A New Annotated Translation, with parallel Latin and Greek Text ed. Bruce W. Frier, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016. Sasanian Iran had its own body of laws which remained in effect for the non-Muslim population of Iran. Parts of them have survived in the form of Madigan i Hazar Dadistan. See: Farraxvmart i Vahrām, Mādigān i Hazār Dādistān. The Book of A Thousand Judgements, ed. and Trans. Anahit Perikhanian and Nina Garsoian, Costa Mesa, California: Mazda Publishers, 1997.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. R. Stephen Humphreys (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 18.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. Rex Smith (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994), 139.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. R. Stephen Humphreys (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 222.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. R. Stephen Humphreys (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 222. The verse of the Qur’an they used was 5:37.

- For example, the writer of Doctrina Jacobi states “Do prophets come on chariots?” (Nathanael G. Bonwetsch (ed.), “Doctrina Lacobi nuper baptizati”, in Abhandlungen der Koiglichen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Gottingen. Philologisch-Historische Klasse: n.F., Band 12, Nro. 3. (Berlin: Weidmannsche Buchhandlung, 1910) Reprint: Liechtestein: Kraus, 1970. 1 – 91.)

- Look at a case where a woman was found to have committed blasphemy against Prophet Muhammad in Sana’a. Muhajir, the governor of Sana’a for Abu Bakr cut off her hand. Abu Bakr wrote to him that the governor should have first established her religion. If she was a Muslim, she must have been treated as an apostate and warranted the death penalty. If she was a non-Muslim, she should have been considered a combatant against whom jihad could be fought. In this particular instance, Abu Bakr snubbed his governor for mutilating a person and advised him to be gentle with people. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. X, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Fred M. Donner (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1993), 192). Probably, Abu Bakr meant if the governor had brought up charges of apostasy, she might have got a chance to repent and might have been pardoned.

- For details see: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 191.

- See above.

- The matter took place in Hejaz, according to Ya’qubi. (Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 816.). Interestingly, Ya’qūbī preserves a tradition attributed to Umar, very similar to that of Ibn Ishaq mentioned above. The venue is different. According to Ya’qubi Umar said at his deathbed “I have recited in the Book of God: The old man and the old woman, [when they have fornicated], stone the two of them definitely as an exemplary punishment from God; and God is all-knowing, wise. Do not turn away from stoning: the Messenger of God stoned, and we stoned; were it not that people would say, “Umar added something to the book of God,” I would write it down with my own hand, for I have recited it in the Book of God.” (Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 794).

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. R. Stephen Humphreys (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 46.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 149.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 158.

- See: Sebeos, Sebeos’ History ed. and trans. Robert Bedrosian (New York: Sources of the Armenian Tradition, 1985), 56, 57, 58.

- Muhammad bin ‘Umar al-Wāqidī. The life of Muḥammad: kitāb al-Maghāzī. Ed. Rizwi Faizer, Trans. Rizwi Faizer, Amal Ismail and AbdulKader Tayob. (London: Routledge, 2011), 423.

- Fartana was one of the singing girls whom Prophet Muhammad sentenced to death at the time of Fath Mecca. She got her pardon after repenting and converting to Islam. (See above).

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Gautier H. A. Juynboll (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 75.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. R. Stephen Humphreys (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 227.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 80.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 230. Once, Umar bin Khattab issued a judgement to amputate the hands of a man who had stolen a she-goat. (Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XXI, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Michael Fishbein (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 177.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 194, 194. By the way, this amputation of his hand was not punishment for any theft. He was a Christian and was not subject to Islamic law. The point here is to emphasize that amputation of hands could result in death.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Yohanan Friedmann (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1992), 19.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 392.

- Sebeos, Sebeos’ History ed. and trans. Robert Bedrosian (New York: Sources of the Armenian Tradition, 1985), 112.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Yohanan Friedmann (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1992), 171.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 162.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. R. Stephen Humphreys (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 55.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 320.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 231.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Gautier H. A. Juynboll (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 72.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Gautier H. A. Juynboll (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 113.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. R. Stephen Humphreys (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 50.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Yohanan Friedmann (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1992), 171.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. Rex Smith (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994), 136.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. X, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Fred M. Donner (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1993), 129.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Yohanan Friedmann (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1992), 106.

- An example where the caliph had to censure a poet: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. Rex Smith (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994), 162.

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), Vol. I, P 36, 38.

- For some building codes of cantonment cities and the materials used to build the houses see: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Gautier H. A. Juynboll (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 68, 69, 78.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVI, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Adrian Brockett (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1997), 66.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVI, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Adrian Brockett (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1997), 66.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 211, 212.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 126.

- William Muir, The Caliphate; its rise, Decline and Fall, from Original Sources (Edinburgh: John Grant, 1915), 184.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. R. Stephen Humphreys (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 231.

- A caravan of pilgrims heard a Bedouin singing on their way to Mecca during Uthman’s tenure. See: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. R. Stephen Humphreys (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 219. However, expressing his virtues in Islam, Uthman says, “I have never sung a song since I accepted Islam. See: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. R. Stephen Humphreys (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 214.

- On his official visit to Jerusalem Umar passed by Adhri’at. Abu Ubayda had reached there to receive him. The people of Adhri’at welcomed them with singers, tambourine players and with swords and myrtle. Umar shouted, “Keep still! Stop them!” Abu Ubayda told Umar, “This is their custom, if though shouldst stop them from doing it, they would take that as indicating thy intention to violate their covenant.” Umar allowed them to continue. (Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 215.

- Muhammad bin ‘Umar al-Wāqidī. The life of Muḥammad: kitāb al-Maghāzī. Ed. Rizwi Faizer, Trans. Rizwi Faizer, Amal Ismail and AbdulKader Tayob. (London: Routledge, 2011), 506.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Gautier H. A. Juynboll (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 85.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. R. Stephen Humphreys (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 230.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. Rex Smith (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994), 142.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 18.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Gautier H. A. Juynboll (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 205.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 231.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Gautier H. A. Juynboll (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 7.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Yohanan Friedmann (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1992), 193.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Yohanan Friedmann (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1992),70, 71.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVI, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Adrian Brockett (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1997), 64.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. R. Stephen Humphreys (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 29, 30.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Gautier H. A. Juynboll (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 151, 152.

- Abu Jandal got prominence in the events of interpretation of the Peace Treaty of Hudaibiyah. See above.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Gautier H. A. Juynboll (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989),151, 152.

- Flogging was gentle. We don’t hear of anybody dying or getting seriously sick after it. Its main aim was to inflict insult publicly.95Abu Jandal became the first Muslim to serve this sentence.

- See: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Gautier H. A. Juynboll (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 153, 154.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 414.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 414.

- One of them was Umar’s own son ‘Ubaydallāh bin ‘Umar. See: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Yohanan Friedmann (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1992), 172.

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 775. Gordon thinks Umar suspected it to be wine. See footnote 977.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 138.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Gautier H. A. Juynboll (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 30.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. R. Stephen Humphreys (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 106.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. R. Stephen Humphreys (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), P 106, footnote 180.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Yohanan Friedmann (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1992), 188, 189.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XI, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Khalid Yahya Blankinship (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1993), 103.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. Rex Smith (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994), 134, 135.

- Umar is particularly known to wear a robe on his head (Al-Imām abu-l ‘Abbās Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 22). It could be part of Umar’s policy to present his public image as a humble down-to-earth earth servant of Allah rather than an arrogant proud ruler.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 419.

- See above.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. Rex Smith (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994), 119.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. Rex Smith (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994), 72.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XV, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. R. Stephen Humphreys (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 229.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 179.

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 821.

- Ibn Ishaq the life of Muhammad Tr. And ed. A. Guillaume (Oxford University Press Karachi 2013; 13th Impression), 606.

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 815.

- Ya’qūbī, Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-, The Works of Ibn Wāḍīḥ al-Ya’qūbī: An English Translation, Eds. and Trans. Matthew S. Gordon, Chase F. Robinson, Everett K. Rowson and Michael Fishbein, (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 816.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 222.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 222.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 223.

- Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 129.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XIII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. Gautier H. A. Juynboll (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 131.

- Ibn Sa’d, Kitāb al Ṭabaqāt al Kabīr, ed. and trans. S Moinul Haq and H. K. Ghazanfar, (Karachi: Pakistan Historical Society, 1967), volume 1, parts 1.20.4.

- Ibn Sa’d, Kitāb al Ṭabaqāt al Kabīr, ed. and trans. S Moinul Haq and H. K. Ghazanfar, (Karachi: Pakistan Historical Society, 1967), volume 1, parts 1.37.35.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 96.

- H. M. El-Hawary, “The Most Ancient Islamic Monument Known Dated AH 31 (AD 652) From The Time of The Third Calif ‘Uthman”, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1930, P 327 AND N. Abbot, The Rise of the North Arabic Script and it’s Kur’anic Development, 1939, University of Chicago Press, pp. 18 – 19 AND A. Grohmann, Arabische Palaographie II: Das Schriftwesen. Die Lapidarschrift, 1971, Osterreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften Philosophisch – Historische Klasse: Denkschriften 94/2. Hermann Bohlaus Nachf: Wein P 71 Plate 10:1.

- Note nisbah of al Hajri. It is related to a place (Hajr in Yamama) rather than the tribe.

- Current location: Cairo Museum of Arab Art, Cairo. See: H. M. El-Hawary, “The Most Ancient Islamic Monument Known Dated AH 31 (AD 652) From the Time of the Third Calif ‘Uthman”, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (1930): 327. AND A. Grohmann, Arabische Paloagraphie II: Das Schriftwesen. Die Lapigarschrift, (Wein: Hermann Bohlaus Nachf, 1971), P 71. Plate 10:1.

- For a detailed study of funerary rituals during early Islam see: Yeor Halevi, Muhammad’s Grave: Death Rites and the Making of Islamic Society. New York: Columbia University Press, 2007.

- Now on display in Rockfeler Museum, Jerusalem, Palestine (Item S. 972). It reads: Here was interned Stephanos of blessed memory, priest, son of Rhginos, on the 19th of the month Hyperberetaios, 5th year of indiction.

- Antiochus Stratego: F. Conybeare, “Antiochus Strategos’ Account of the Sack of Jerusalem (614),” English Historical Review 25 (1910), 502 – 517.

- The Christians used to inter the bodies of pious people inside the church.

- Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 217.

- In this particular case Ibn Muljam couldn’t resist investigating. He found that Abjar’s son, Ḥajjār had accepted Islam by that time. See: Abū Jā’far Muḥammad bin Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The History of al- Ṭabarī. Vol. XVII, ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater, trans. G. R. Hawting (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 217.