Culture and politics are shaped by the economy which, in turn, is moulded by geography. It is customary to briefly discuss the geography of the Arabian Peninsula before going into any details of her history.

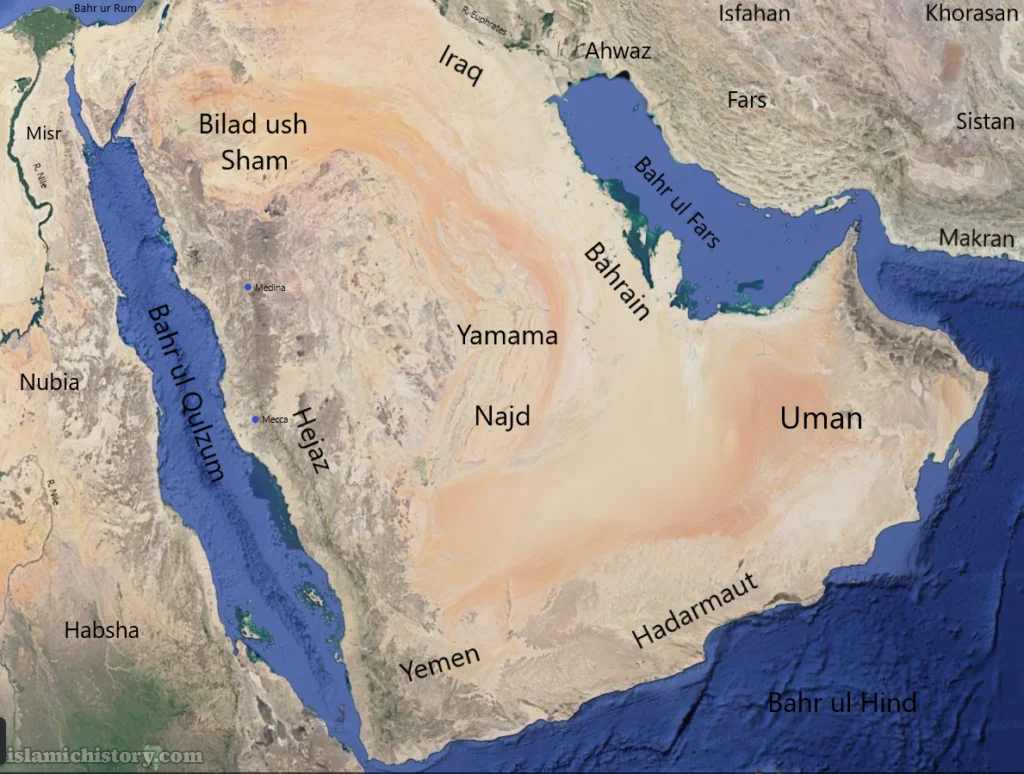

The Arabian Peninsula, abbreviated as Arabia, is surrounded by the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, Arabian Sea, Gulf of Oman and the Persian Gulf on three sides. 1 As shown in map I, its land mass is contiguous with Mesopotamia and the Syrian Desert. Here the boundary between Arabia and the rest of Asia is fuzzy. It is arbitrarily defined as running from just to the near right bank of River Euphrates in the east to the steppes of the Syrian Desert in the west. 2

The Arabian Peninsula, called Jazīrat ul Arab (جزيرۃالعرب) by Arabs themselves, is thus a big chunk of land about 3.25 million square kilometers, roughly equal to the size of India. In terms of the American continent, it is roughly equal to the combined area of seventeen states of the USA called the Southern United States. In terms of the European continent, it is roughly the size of the European Union in 2004 (Eu-15). Currently, it accommodates six countries, namely Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Oman, United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and Qatar in their entirety and further four countries namely Jordan, Syria, Iraq and Kuwait partially.

Syrian Steppe

The Red Sea littoral extending from the Gulf of Aqaba in the north to Bab al Mandeb in the south is almost 2000 kilometres and the distance from Bab el Mandeb in the west to Ras al Hadd in the east is roughly the same.

Tihamah (Tihāmah. Tihama تہامہ) is the name given to the plain that runs along the Red Sea coast of Arabia. Though quite constricted and sometimes non-existent in the north, it widens south of the port of Yanbu to roughly 80 kilometres, further widening up to 130 kilometres in Yemen (يمن)

Tihamah ends abruptly in an escarpment at its western end. This is the main mountain range of Arabia. It stretches all the way from the northern end of the peninsula down to the south, becoming wider and higher while reaching south. Around Mecca (Makkah مكّه), about midway down its length, this mountain chain has a break separating modern-day Hejaz (Hijāz حجاز) in the north from Asir (Asīr عسير) in the south.3 Southernmost peaks of this mountain chain in Asir rise up to 3000 meters.

Tihamah; Glimpse of the sea can be seen near horizon.

Mountains of Hejaz

To the west of this imposing mountain, the chain is the central plateau (highland) called Nejd (نَجَد Najd). With an average elevation of 900 meters, it slopes down gently from west to east. Nejd plateau is interspersed by small mountain systems here and there like Jabl Tuwayq (طوىق جبل). 4 Eastern end of the Nejd Plateau merges into the low and flat plains of Hasa (الاحساء). 5 Hasa plain touches the eastern coast of the peninsula, washed by Persian Gulf. In the north, it is continuous with the plain of Iraq (‘Irāq عراق) called Jazirah (al-Jazīrah الجزىره) and in the south, it extends into the plain of Oman (Umman Ummānعمّان ). Hasa plain has numerous salt pans called sabkha (سبخه).

Jabl Tuwayq

Arabia has another mountain range stretching along the southeastern peninsula’s southeastern end. These mountains show a steady increase in altitude westwards as they approach present-day Yemen from Oman. Their highest point, Jabl An-Nabi Shu’ayb (شعيب النبى جبل) in Yemen, is 3666 meters above sea level.

Sabkha of Hasa Plain

Ancient volcanic activity has created many volcanic fields in the northern part of Arabia called ḥarrah (حره). The largest of them is Harrat ash Shaam (الشام حرۃ) which spreads from north-western Saudi Arabia into Jordan and Southern Syria.

The Tropic of Cancer passes through the center of the Arabian Peninsula, though there is nothing tropical about this region. Except for the hilly areas of Yemen and Asir, the peninsula is arid.

Tihamah coastal plain is dry, sometimes interspersed with marshes though. Thanks to the Red Sea, Tihamah is cool. Daytime temperature during summer averages 32°C while winter temperature is around 16°C. These regions receive regular rainfall. Humidity on the coast is so high in the summer that a mist often sprinkles the coastal areas in the daytime and a warm fog hangs in the air at night. Tihamah can receive a surprisingly cool, humid breeze in summer.

Coastal regions on the gulf coast are a mirror image of Tihamah as far as their weather is concerned.

Lush green Wādi Iliab in Asir

The Asir, Yemen and Dhofar (Ẓufār ظفار) regions of present-day Oman receive up to 30 cm of rainfall per year, mainly due to monsoons that come from October through March from the Indian Ocean. This area supports terrace farming. The highlands of Yemen have even few clusters of Junipers and boast a hundred-kilometre-long river, Hajr (Wādi al Hajr الحجر وادى). That is the only river on the peninsula, though it is seasonal. On the other hand, Hejaz and Nejd receive only 4 cm of rain per year on average. It translates into a couple of showers in a year, though they can be torrential, flooding wādi (وادي), the dry river beds formed by running of rainwater for millennia. This little water allows the growth of grass, shrubs and scattered acacia and tamarisk trees, supporting grazing. Some areas might not receive a single shower for years, producing drought. Nejd’s northern part rarely receives any rain. It has converted into a totally barren stony and sandy desert called Nefud (Nefūd نفود).

Wādi

The sand of Nefud has a reddish tinge due to the presence of iron ores. The Nefud merges into the Syrian Desert towards the north. The lower third of the Nejd plateau is another desert, devoid of any life, called Ruba al Khali (Ruba ul Khāli الخالى ربع). Ruba al Khali does not receive any rain. It has a reputation for being the largest contiguous sand desert on the planet and the most desolate region of the world. Its sand is estimated to be 180 meters deep. Nobody has ever dwelled here but ancient Arabs used to cross it on camels.

Ruba ul Khāli

Along the side of Jabl Tuwayq and towards its east is the long and narrow Dahna (Dahna’ الدهناء) desert. It is a narrow strip of sand that connects Ruba al Khali with Nefud.

Oasis

Summer is hot in Hejaz, Nejd and its deserts. Temperature averages around 45C° and may reach up to 54C° on a hot summer day. December and January are the coolest months. Though temperature averages around 14C° in winter, high wind produces biting cold. Rarely, the temperature falls to even a freezing point.

Underground water comes near the surface in some arid places. Sometimes this water starts running on the ground as a spring. Otherwise, it can be tapped by digging well. Agriculture is possible in such areas and has been practiced since ancient times. These areas are called oases (wāḥtah واحۃ). Oases not only grow dates but also cereals. Such groundwater is most abundant in Hasa plain producing the largest oases on the peninsula, named Hofuf (Hofūf الھفوف). However, only 1% of the land area of Arabia is covered with oases. 6

Sand storm in desert

Sand storms and dust storms are natural hazards in Arabia. The worst sand storms are associated with shamāl (شمال), the north-westerly wind that is strongest in summer.

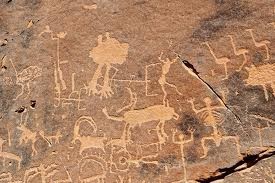

Arabian rock art Ostrich, ibex, long-horned cow recognizable

Desert-adapted wildlife is present throughout. Rock graffiti drawn by pre-historic hunter-gatherers at Jubbah in Nefud desert near Hail (Ḥāʾil حاءل) at Qaryat al-Asba, in the west of Riyadh and many other sites, depict ostrich, long-horned cow, ibex, camel, hyenas, lions and leopard. Great herds of gazelles, oryx and ibex roamed all around Arabia. They have got extinct just in near past. Asir still supports a population of baboons, mountain sheep and mountain goats. Wildcats, wolves, jackals, foxes, rabbits, porcupines, honey badgers, mongoose, sand rats, jerboas and sand cats still survive in many parts. A number of snakes, skinks and lizards also dwell in the peninsula. Falcon and eagle dominate the sky.

Now, the question arises, was Arabian topography and climate in pre-Islamic centuries similar to the present one? Research has shown that nothing much has changed since the 6th century CE.7 Current climatic and topographic conditions of Arabia can safely be applied to pre-Islamic and early Islamic.

Political Regions of Pre-Islamic Arabia

The political division of Arabia in the pre-Islamic and early Islamic eras was totally different from the current one. Pre-Islamic Arab poets have mentioned many Arabian regions by their specific names indicating that Arabs of that time did not consider the entire peninsula as one political entity. Extant geographic writers agree with this assertion.

For example, a Christian cleric writing in southwest Iran in CE 650’s pens down: Hasor, which scripture mentions as being the ‘head of the kingdoms’ [Joshua 11.10] belongs to the Arabs. Medina was named after Midian, the fourth son of Abraham by Ketura, and it is also called Yathrib. Dumat Jundal [modern al-Jawf] and the land of Hagaraye are abundant in water, palm trees, and fortified buildings, and in the same way, the land of Hatta, [Khatt, in the modern United Arab Emirates] is located on the seashore near the Islands of Qatar, is abundant and dense too in many kinds of plants. Likewise, is the land of Mazon [Oman], also situated on the seashore – its land measures more than a hundred parsing, the land of Yamama located in the middle of the desert; the land of Tawef [Taif], and the city of Hirra which was established by King Mundhir who was called ‘the Mighty’ – he was the sixth since the beginning of the Ishmaelite kings.8

Accurate determination of the political boundaries of pre-Islamic political entities is difficult. However, analysis of such extant writings, as above and study of pre-Islamic Arabic poetry creates at least a blurry picture of political regions of pre-Islamic Arabia.9 That is drawn in map II. Many cities from 5th and 6th centuries CE still exist. Ruins of some have been excavated and their names identified. Many others are mentioned in contemporary sources but their location is still unknown. Selected settlements of that time are shown in map III.10

Pre-Islamic Mecca

Special mention is needed for Mecca and Medina (Madīnah مَدىِنه). The date of birth of Mecca is not known.11 Arab sources claim that Abu Karab Asʾad Tubba’ (تبع) had donated the kiswah (كِسوة) of Ka’ba (cloth that covers the Ka’ba).12, 13 As a dated inscription verifies Abu Karab ruling Ḥimyar (Himyarite) kingdom in August 433 CE, it can be assumed that Mecca existed by that time.14

Mecca, per se, is not mentioned in any pre-Islamic source. Ibn Ishaq writes that Mecca was also called Bakka because it used to break the necks of tyrants.15 Guillaume suggests that the root of this word is the Arabic verb bakka meaning ‘he broke’. Lately, some scholars have suggested that biblical Baca was actually Mecca and that it is mentioned in the Qurʾān (Quran Qur’an Koran قرآن) by the same name.16, 17, 18, 19 Qurʾān also calls this town by name of Mecca at least once.20 On many other occasions the Qurʾan mentions ‘sacred mosque’ (masjid il Ḥarām) without naming the locality. It is plausible that Mecca was known as Bakka or another similarly sounding name in pre-Islamic times.21 This could be the reason that we don’t find the name ‘Mecca’ in pre-Islamic sources.

The name of the town aside, some historians are debating its pre-Islamic location. Diodorus Siculus, a Greek historian of 1st Century BCE, wrote a book, Bibliotheca Historica. He mentions in this book that the Banizomenes people had set up a temple located on the coast of the Red Sea exceedingly revered by all Arabs.22 Since he doesn’t mention the place of the temple by name, this hint does not automatically establish as a fact that Diodorus is mentioning the Ka’ba and Mecca. Similarly, Ptolemy of Alexandria, who was a 2nd century CE geographer, shows a place in his map by name of Macoraba in Arabia Felix (south Arabia) at a latitude of 73 degrees, 20 minutes and a longitude of 22 degrees in his book Geographia.23 Ptolemy also mentions another town in Arabia in his same work, by the name of Moka. 24 Crone rejects either of these cities to be Mecca. She argues that the positions of these places mentioned by Ptolemy are far from the current location of Mecca, which is currently located at 21 degrees, 41 minutes north and 39 degrees, 81 minutes east.25 Sergeant, on the other hand, calls this assertion of Crone polemic.26

Actually, the oldest historical material that mentions Mecca clearly by name is Armenian geography, Ashkharhatsuyts, guessed to be written between 591 CE to 636 CE and attributed to Ananias of Shirak. It says “…it is bounded on the south by Fortunate Arabia, on the east by Desert Arabia, and on the north by Syria and Judaea. It has five small districts near Egypt, Tackastan, the Munuchiatis Gulf by the Red Sea [other side of Sinai], and Pharanitis, where the town of Pharan, which I think Arabs call Mecca. Here begin the mountains called Melana which extend northwards turning slightly to the east, then the Elanites [Gulf of Aqaba] which is near a plateau. Fortunate Arabia contains the River Tretenon but not a single spring. It is six degrees long and two wide.”27 Though the location of Mecca is vague in this account, its time of writing nearly coincides with the advent of Islam. At least, the town was known by its current name at the time of advent of Islam. A later historical source that mentions Mecca by name is “The Anonymous Chronicle of 741CE.” This history, written in Spain, is dated not to be earlier than 741 CE. This chronicle mentions Mecca in context of the war between the Umayyads and Abdullah bin Zubayr. Even in this chronicle, its location is told to be between Ur of Chaldees and Carras, the city of Mesopotamia.28

By the way, Procopius, a Byzantine historian of the 6th century CE, while describing the wars of Justinian, provides his reader with a survey of the entire coast of western Arabia as it was known in the mid-6th century.29 He does not describe Mecca (or Ptolemy’s Makorabo), and neither does he describe Quraysh. But again, one may argue that he was describing the coast, not inland Arabia. The absence of the name of Mecca in pre-Islamic sources has generated a heated debate among scholars about the exact location of Mecca in pre-Islamic times. This debate got spicier when Gibson pointed out that the direction (qibla qiblah قبله) of some of the earliest Islamic mosques does not face towards the current location of Mecca. 30 Gibson had used Google Maps to ascertain the direction of the qibla of those mosques. Generally, historians did not take Gibson’s observation seriously and they insisted that the ‘general direction’ of the qibla of all first Islamic century mosques was the current location of Mecca.

In any case, until this scholarly debate settles, we shall assume that Mecca has been in existence at its current location from pre-Islamic times and that absence of its name in pre-Islamic sources does not automatically mean its non-existence.

Mecca was not suitable for agriculture and its only reason for existence was trade and the presence of Ḥaram. 31 Since Mecca did not support agriculture, it was through trade and the economic benefit associated with the pilgrimage to its shrine, the Ka’ba, that the Meccans were able to live. 32

Pre-Islamic Medina

Contrary to Mecca, Medina, whose ancient name was Yathrib (Yethrib يثرب), is clearly identified at its present location by pre-Islamic sources. Inscription of Nabonidus, dating from 552 BCE or little after and discovered at Harran (Sultantepe) near present-day Urfa in south-eastern Turkey, reads ‘I hied myself afar from my city Babylon (on) the road to Tema’, Dadanu [Dedan = al-Ula], Padakku [Fadak], Hibra [Khaybar], Ladihu [Yadi.’?] and as far as Latribu [Yatribu = Yathrib]; ten years I went about amongst them, [and] to my city Babylon I went not in’.33

Similarly, a Minean inscription found near the ancient city of Ma’in in South Arabia (datable to the second half of the first millennium BCE), records some form of registration of women from various non-Minean lands, and mentions two originally from Ytrb (Yathrib).34

The continued existence of this settlement is evident from the fact that Lathrepta/Lathrippa was included among towns of the inland parts of Arabia Eudaemon by the second-century geographer Ptolemy, who failed to mention Mecca.35 Lathripa is also mentioned by Stephanus of Byzantinus (c. 528-35 CE) who locates it near Hegra. 36 Hegra was the Greek name of al-Hijr currently called Madain Saleh. Lastly, an inscription (Murayghān 3) written by Abraha shortly after 552 CE and discovered in 2009, announces the establishment of his authority over various areas of Arabian Peninsula, including Ytrb.37 Hence there is ample evidence that Medina existed at its current location for at least a millennium before the advent of Islam. Qurʾān calls this town by name of Yathrib.38

End Notes

- For details of the geography of the Arabian Peninsula see: Paul Sanlaville, “Geographic Introduction” in Roads of Arabia, ed. ‘Ali ibn Ibrāhīm Ghabbān, Beatrice Andre-Salvini Francoise Demange, Carine Juvin and Marianne Cotty, (Paris: Louvre, 2010), 55 – 68. Also see: Peter Vincent, Saudi Arabia: an Environmental Overview, London: Taylor & Francis, 2007. AND William Bayne Fisher, The Middle East. A Physical, Social and Regional Geography, (London: Methuen & Co. Ltd, 1952).

- Classical geographers define Arabia as the land of Arabs. (Pliny the Elder (C. Plinius Secundus), Natural History, ed. and trans. H. Rackham (London: W. Heinemann and Cabridge, Harvard University Press, 1938 – 1956) Vol. VI P. 32). Pliny (d. 79 CE) not only includes Arabian Peninsula in the land of Arabs but extends its borders to much of Syria, Mesopotamia and the eastern desert of Egypt – all regions occupied by Bedouins of the classic texts. To find the extent of Bedouin distribution in the 4th century CE see: Altheim Franz and Ruth Steihl, “Shāpūr II. und die Araber,” in Die Araber in der alten Welt, (Berlin: W. de Gruyter, 1964 – 1969) Vol II P 344 – 356.).

- For a detailed description of Hejaz see: Alois Musil, The Northern Ḥeijāz: A Topographical Itinerary, (Prague: Czech Academy of Sciences and Arts, 1926).

- For a detailed description of Nejd see: Alois Musil, The Northern Nejd, (Prague: Czech Academy of Sciences and Arts, 1928).

- Federico S. Vidal, The Oasis of al-Hasa, (New York: Arabian American Oil Company, 1955) AND Charles H. V. Ebert, Water Resources and Land Use in the Qatif Oasis of Saudi Arabia, Geographical Review Vol 55, no 4 (1965), 496 – 509.

- For description of Medina and other large oases of the northern Hejaz on the eve of Islam, see: Julius Wellhausen, Medina vor dem Islam: Muhammads Gemeindeordnung von Medina, (Berlin: Druck Und Verlag Von Georg Reimer, 1889). See also: Henri Lammens, La Cite arabe de Taif a la veille de l’Hegire, (Beyrouth: Imprimerie Catholique, 1922).

- Vincent Kotwicki and Zaher Al Sulaimani, “Climates of the Arabian Peninsula – past, present, future,” International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management 1, no.3 (2009): 297 – 310.

- Anonymous, (the Chronicle of Khuzistan). A Short Chronicle on the End of the Sasanian Empire and Early Islam: 590 – 660 A.D. ed. and trans. Nasir al-Ka’bi. (Poscataway, JN: Gorbias Press, 19160, 110 – 114.

- Al Ḥasan al-Hamadāni. Ṣifat Jazirat al-arab, ed. D. H. Mùller, (Leyden, 1884) is a valuable work on Arab Geography of the early Islamic centuries. Its author Hamadāni lived from c. 893 to 945 CE. Muhammad al-Muqaddasi. Ahasan al-Taqasim fi Ma’rifat al-Aqlim, ed. and trans. Basil Anthony Collins (Reading: Garnet Publishing, 1994) is another book from those times on Geography. Its author, Muqaddasi lived from c. 945 to 991 CE. Yaqut al-Hamawi. Kitāb Mu’jam al-Buldan (Beirut: Dār iḥyāʾ al-trāth al-‘Arabī, 1996) is another valuable source of Geography of later Islamic centuries. Its author Yaqut lived from c. 1179 to 1229 CE. Scholars believe that information contained in these books can be equally applied to pre-Islamic Arabia and all these works are well cited by modern historians on Arabs.

- “Maps of Middle East,” Center for Middle Eastern Studies: The University of Chicago. Accessed March 20, 2017, https://cmes.uchicago.edu/page/maps-middle-east. This site contains a number of maps of the Middle East from that period.

- Jacqueline Chabbi, “The origins of Islam,” in Roads of Arabia, ed. ‘Ali ibn Ibrāhī.m Ghabbān, Beatrice Andre-Salvini Francoise Demange, Carine Juvin and Marianne Cotty, (Paris: Louvre, 2010), 101.

- Muḥammad Ibn Ishaq. The Life of Muhammad, ed. and trans. Alfred Guillaume (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2013), 9.

- Abu Karab is also known as Abu Karib.

- For inscription see: Christian Robin, “Le Royaume Ḥujride, dit ‘royaume de Kinda’, entre Ḥimyar et Byzance,” Academie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, Comptes rendus (1996): 665-714. Ry 534 + MAFY-Rayda 1.

- Muḥammad Ibn Ishaq. The Life of Muhammad, ed. and trans. Alfred Guillaume (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2013), 47.

- “Ka’bah As A Place Of Worship In The History,” Islamic Awareness, M S M Saifullah. Accessed March 21, 2017, www.islamic-awareness.org/history/kaaba.html.

- Baca in the Bible: Psalm 84:6.

- Baca in the Qur’an: 3:96.

- Bible is the holy book of the Christians. Qurʾān is the holy book of Muslims. Muslims believe that Allah revealed the Qur’an to the Prophet Muhammad, the founder of Islam.

- Qurʾan 48:24.

- This plausibility gets further support when we hear from another Islamic source, Balādhuri, that Mecca was called Ṣalāḥ in pre-Islamic times. (Aḥmad ibn-Jābir al-Balādhuri. Kitāb Futūh al-Buldān, ed. and trans. Philip Khūri Ḥitti, (New York: Columbia University, 1916), 80).

- Diodorus of Sicily: In Twelve Volumes, trans. C H Oldfather (London: William Heinmann Ltd, 1935), vol. II, P 217.

- Claudius Ptolemy. The Geography, ed. and trans. Edward L. Stevenson (New York: New York public library, 1932). Repr. New York: Dover, 1991.

- Claudius Ptolemy. The Geography, ed. and trans. Edward L. Stevenson (New York: New York public library, 1932). Repr. New York: Dover, 1991.

- For Crone’s discussion see: Patricia Crone. Mekkan Trade and the Rise of Islam (Pisataway, New Jersey: Gorgias), 134 – 37.

- R. B. Serjeant, “Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam: misconceptions and Flawed Polemics,” Journal of the American Oriental Society (1990): 472.

- Anania Shirakatsi. The Geography of Ananios of Sirak (Asxarhoc ‘oyc’): The Long and Short Recensions, trans. R. H. Hewsen (Wiesbaden: Reichert, 1992), 71.

- Corpus scriptorium Muzarabicorum, ed. Fernandez J. Gil (Madrid: Instituto Antonio de Nebrija, 1973), Vol 1 P7-14. AND The Byzantine-Arab Chronicle of 741 in: Robert G. Hoyland, Seeing Islam as Others saw it (Princeton, NJ: The Darwin Press, 1997), 622.

- Procopius. History of the Wars, Books I and II, ed. and tans. H. B. Dewing (London: William Heinemann, 1914), 181 – 83.

- Dan Gibson. Qurʾānic Geography (Surrey B.C: Independent Scholar’s press, 2011), part VI.

- Fred M. Donner, The Early Islamic Conquests, (Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 1981), 15. See also: Fred McGraw Donner, “Mecca’s food Supplies and Muhammad’s Boycott,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. Vol 20, No 3 (Oct, 1977): 249 – 266.

- Fred M. Donner, The Early Islamic Conquests, (Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 1981), 51.

- Cyril C. Gadd, “the Harran Inscriptions of Nabonidus,” Anatolian Studies 8 (1958): 80, 84. And Pl. I – XVI.

- Kenneth A. Kitchen. Documentation for ancient Arabia. Part II, Chronological Framework & Historical Sources. (The world of ancient Arabia Series) (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2000), 411

- Ptolemy. The Geography. 1932.

- Stephanus Byzantinus. Ethnika, ed. Meineke, trans. Margarethe Billerbeck and Zubler, (Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter, 2006 – 2015), 258-9.

- Christian J. Robin and Sālim Tayran, “Soixante-dix ans avant l’islam, l’Arabie toute entière dominèe par un roi chrètien,” dans Acadèmie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, Comptes rendusde l’annèmie (2012): 525 – 553.

- Qurʾān 33:13.